Demystifying CLIP Data

[clip multimodal dataset deep-learning constrast-loss transformer This is my reading note for Demystifying CLIP Data. This paper reverse engineered the data of CLIP and replicated even outperformed the CLIP.

Introduction

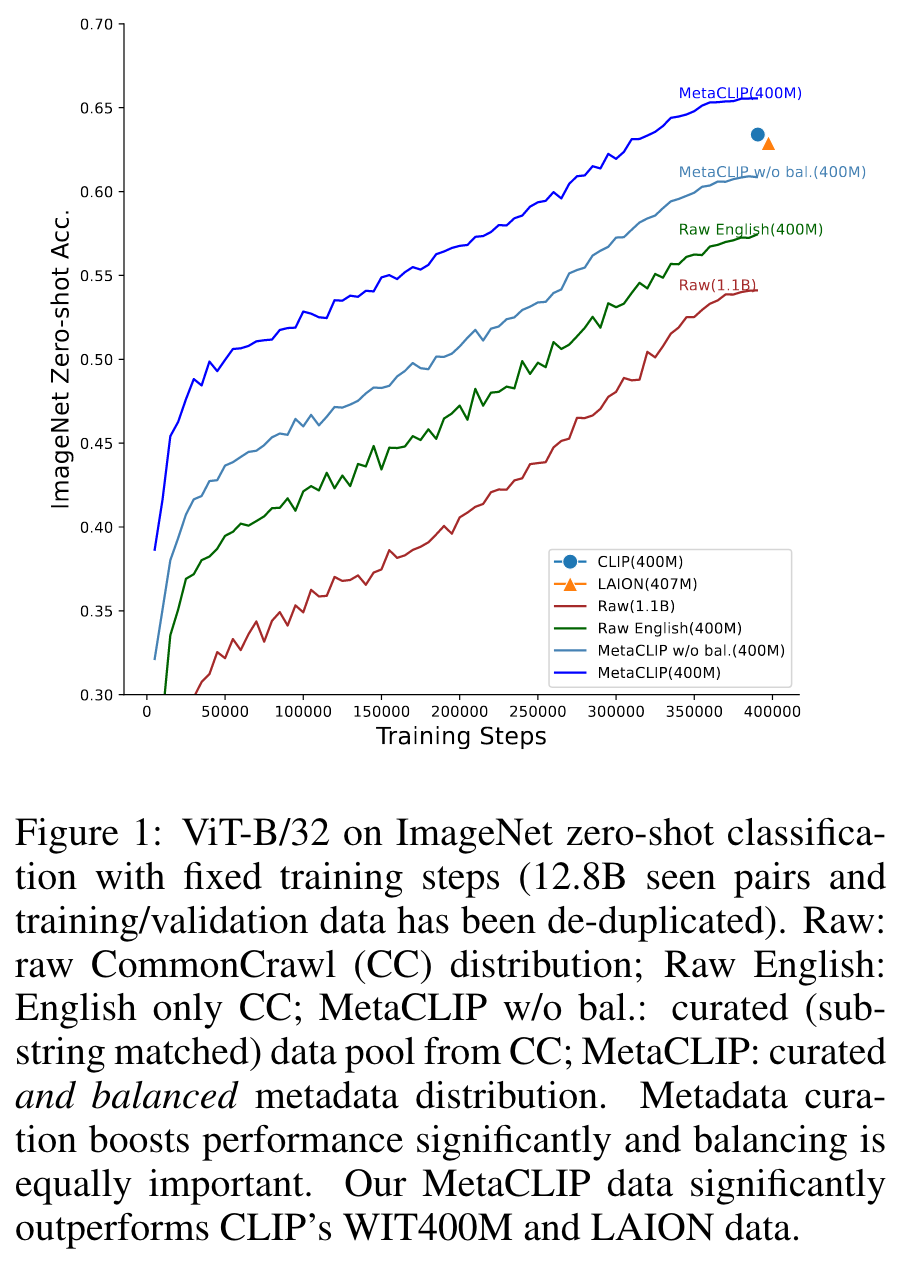

We believe that the main ingredient to the success of CLIP is its data and not the model architecture or pre-training objective. In this work, we intend to reveal CLIP’s data curation approach and in our pursuit of making it open to the community in- troduce Metadata-Curated Language-Image Pre-training (MetaCLIP). MetaCLIP takes a raw data pool and metadata (derived from CLIP’s concepts) and yields a balanced subset over the metadata distribution. MetaCLIP applied to CommonCrawl with 400M image-text data pairs outper- forms CLIP’s data on multiple standard benchmarks. (p. 1)

Related Work

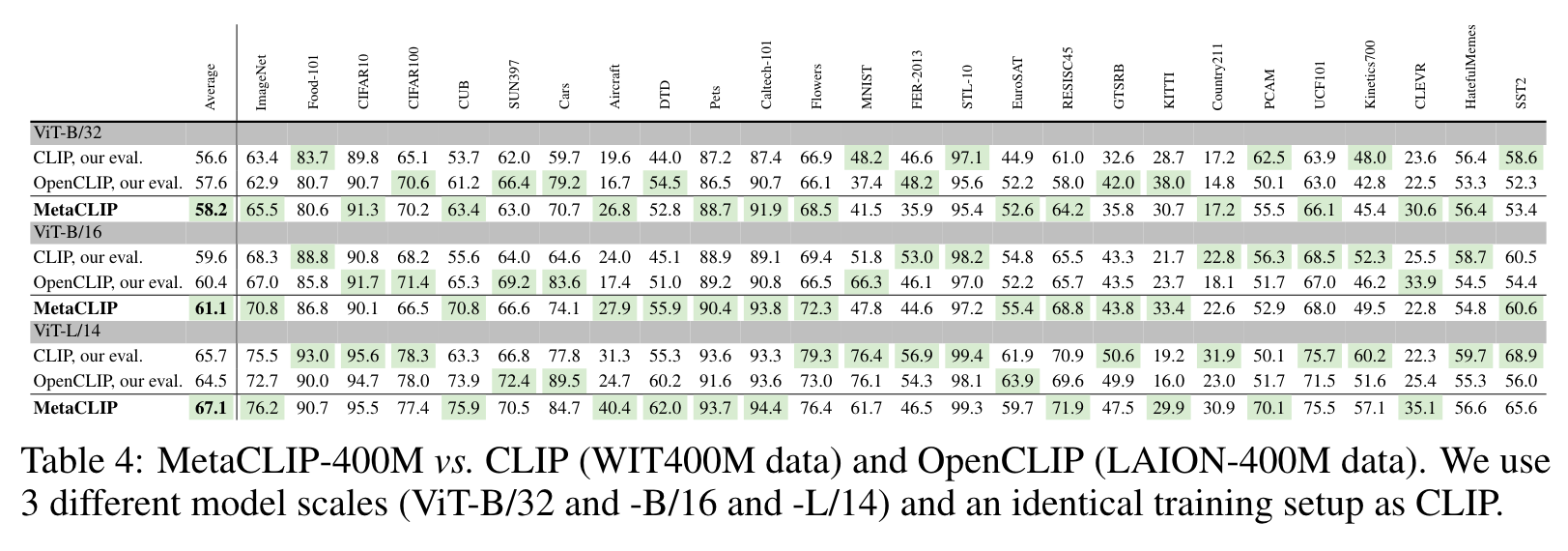

Recent efforts, such as LAION (Schuhmann et al., 2021; 2022) and concurrent work DataComp (Gadre et al., 2023), attempt to replicate CLIP’s training data. However, they adopt fundamentally different strategies for several reasons. First, the data used in these approaches are post-hoc, filtered, by vanilla CLIP as a teacher model. Second, the curation process in these methods relies on a labor-intensive pipeline of filters, making it challenging to comprehend the resulting data distribution from the raw Internet (refer to the unknown biases of using CLIP filter in (Schuhmann et al., 2022)). Thirdly, the goal is to match the quantity of CLIP’s target data size rather than the data distribution itself, which may lead to an underestimation of the data pool size needed to obtain sufficient quality data. Consequently, the performance on the 400M scale is sub-optimal, with LAION400M only achieving 72.77% accuracy on ViT-L/14 on ImageNet, whereas vanilla CLIP obtains 75.5%. (p. 3)

METACLIP

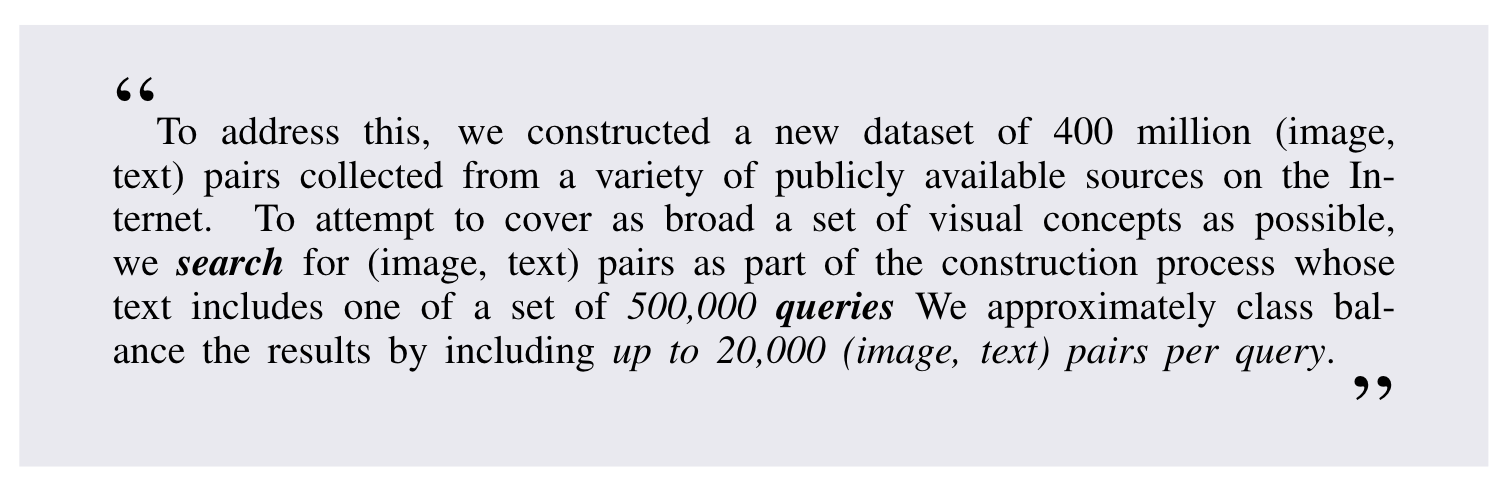

CLIP’s WIT400M is curated with an information retrieval method, quoting (Radford et al., 2021): (p. 3)

METADATA CONSTRUCTION: M = {entry}

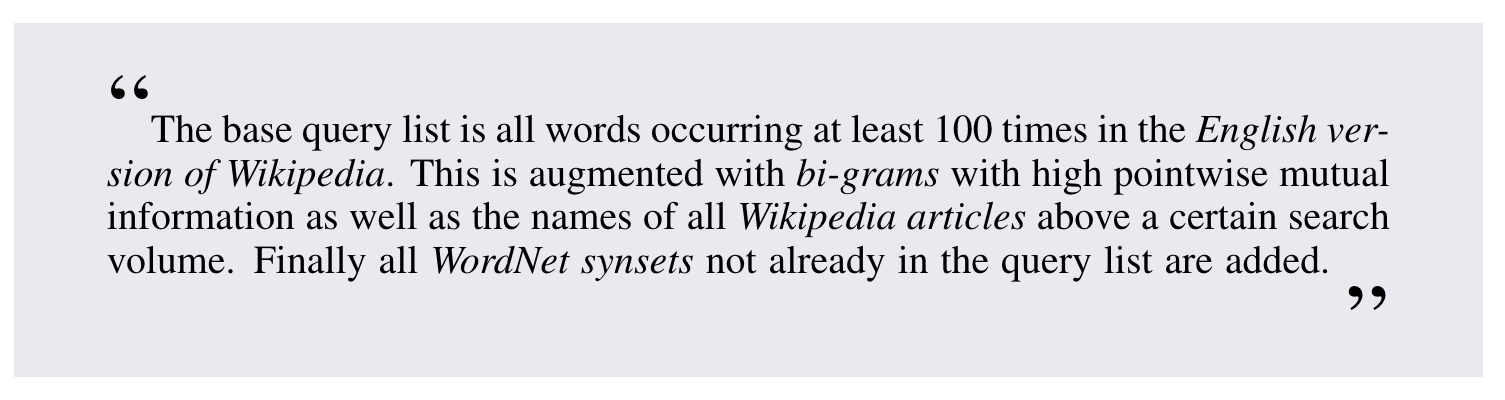

We start by re-building CLIP’s 500,000-query metadata, citing Radford et al. (2021): (p. 3)

The metadata (‘queries’ or ‘entries’) consists of four components: (1) all synsets of WordNet, (2) uni-grams from the English version of Wikipedia occurring at least 100 times, (3) bi-grams with high pointwise mutual information, and (4) titles of Wikipedia articles above a certain search volume. (p. 4)

SUB-STRING MATCHING: text → entry

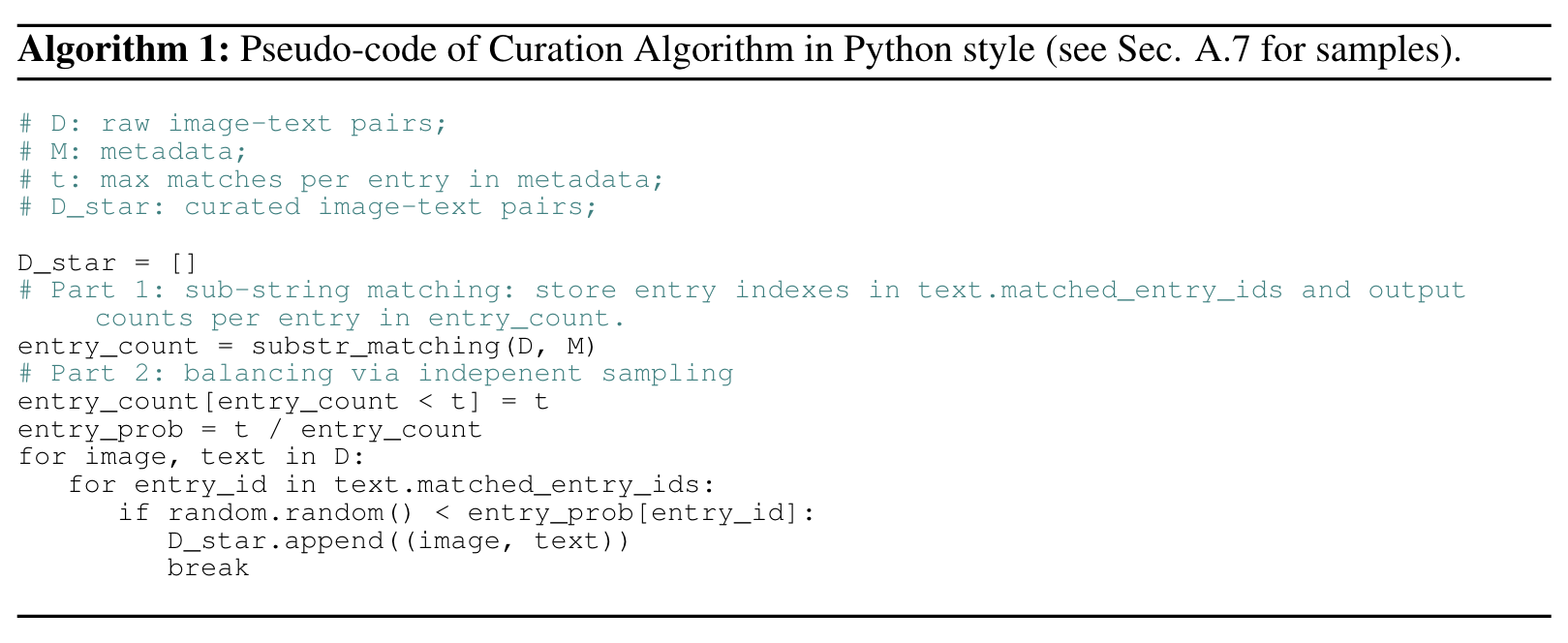

This process identifies texts that contain any of the metadata entries, effectively associating unstructured texts with structured metadata entries. (p. 4)

Image-Text Pair Pool

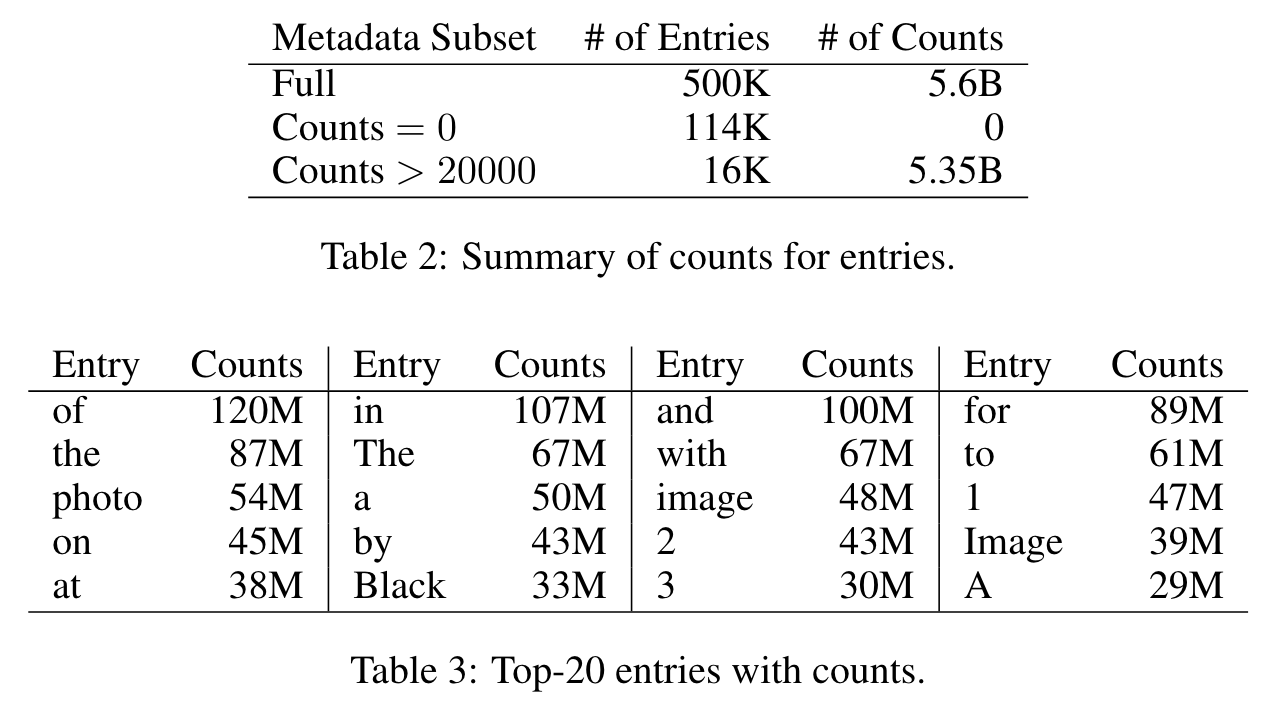

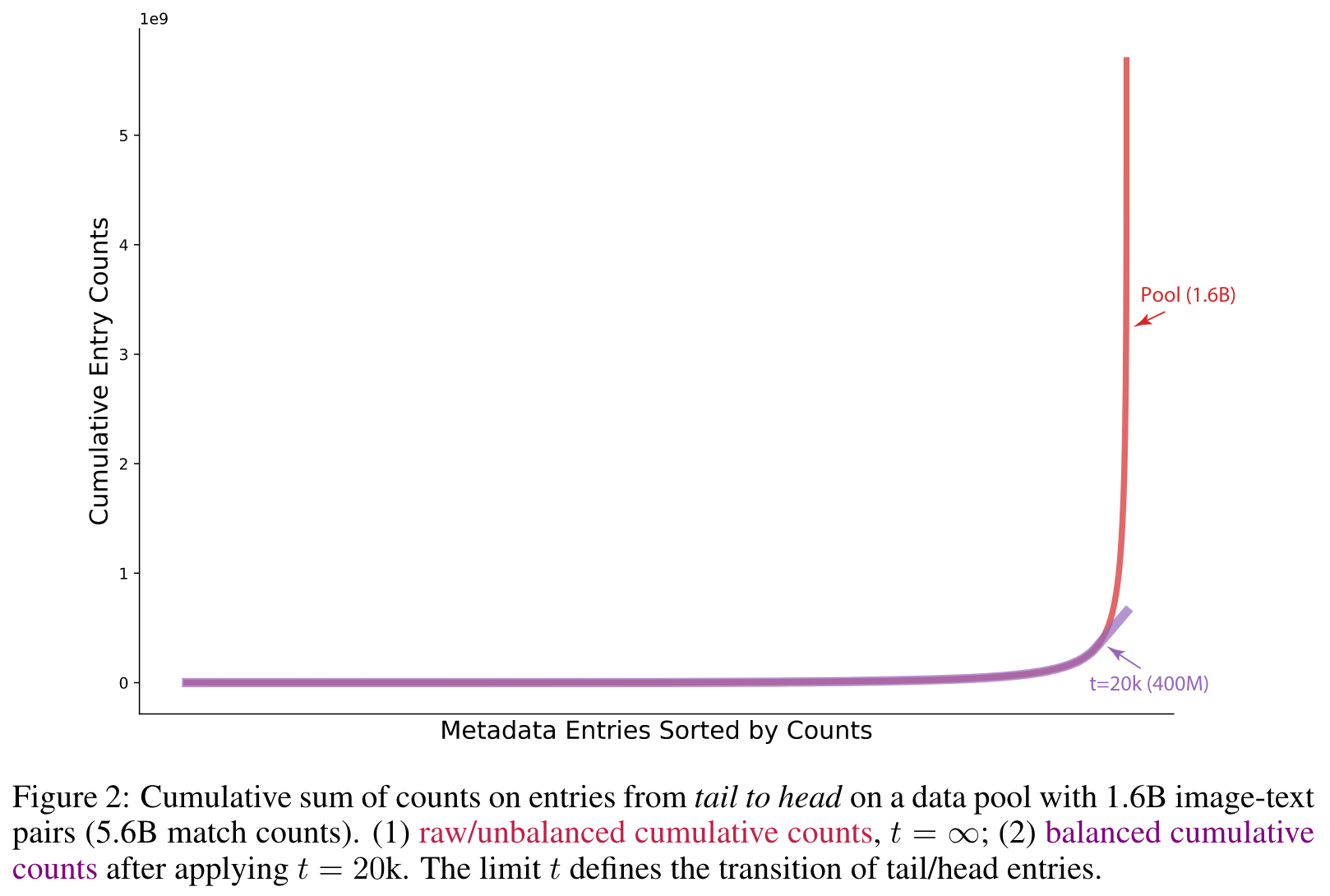

We adopt CommonCrawl (CC)4 as the source to build such a pool and re-apply sub-string matching to this source. We ended with a pool of 1.6B image-text pairs (5.6B counts of sub-string matches). Note that one text can have multiple matches of entries and we have 3.5 matches per text on average.

As a result, sub-string matching builds the mapping txt → entry. This step has two outcomes: (1) low-quality text is dropped; (2) unstructured text now has a structured association with metadata. For all English text, ∼50% image-text pairs are kept in this stage. Similar to CiT (Xu et al., 2023), this approach looks for quality matches and automatically gets rid of some type of noise (such as date strings) that a typical filter system would remove consider case-by-case (e.g., regular expression on dates, ids etc.). (p. 4)

INVERTED INDEXING: entry → text

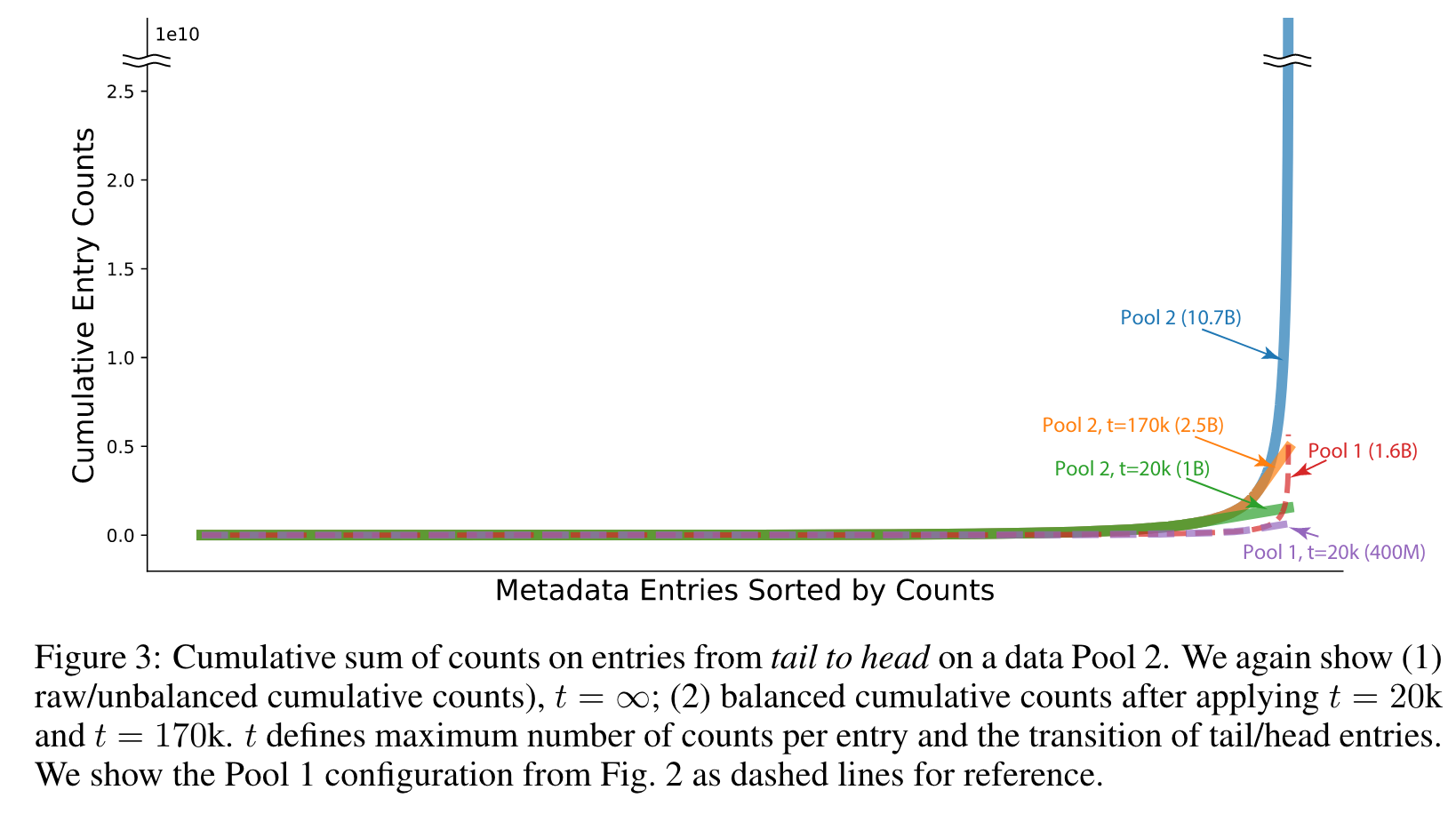

We observed that only 16k entries had counts higher than 20k, accounting for only 3.2% (16k/500k) of the entries, but their counts made up 94.5% (5.35B/5.6B) of the total counts of all entries. (p. 5)

QUERY AND BALANCING WITH t ≤20K

The key secret behind OpenAI CLIP’s curation is to balance the counts of matched entries. For each metadata entry, the associated list of texts (or image-text pairs) is sub-sampled, ensuring that the resulting data distribution is more balanced. This step aims to mitigate noise and diversify the distribution of data points, making the data more task-agnostic as foundation data for pre-training. (p. 5)

The magic number t = 20k is a threshold used to limit the number of texts/pairs for each entry. Entries with fewer than t pairs (tail entries) retain all associated pairs, while entries with more than t pairs (head entries) are sub-sampled to t pairs. (p. 5)

Interestingly, the value of t = 20k seemingly represents the transition from tail to head entries, when the head entries start exhibiting an exponential growth rate. (p. 5)

- It reduces dominance and noise from head entries, like common web terms. E.g., out of 400M pairs, only 20k texts containing “photo” are kept (while there are 54M “photo” instances in the pool).

- It diversifies the data distribution and balances tail/head entries, leading to a more task-agnostic foundation.

- Sampling for each entry ensures that data points with more matched entries or denser informa- tion are prioritized for curation. (p. 6)

Discussion

CLIP employs a pure NLP-based approach, requiring no access to ML models and minimizing explicit/implicit priors from humans. The metadata plays a central role in mitigating noise and preserving signal in the data distribution. The balancing step effectively flattens the data distribution, diversifying the data and making it more suitable as foundation data for pre-training tasks. (p. 6)

A SIMPLE ALGORITHM FOR CURATION

EXPERIMENTS

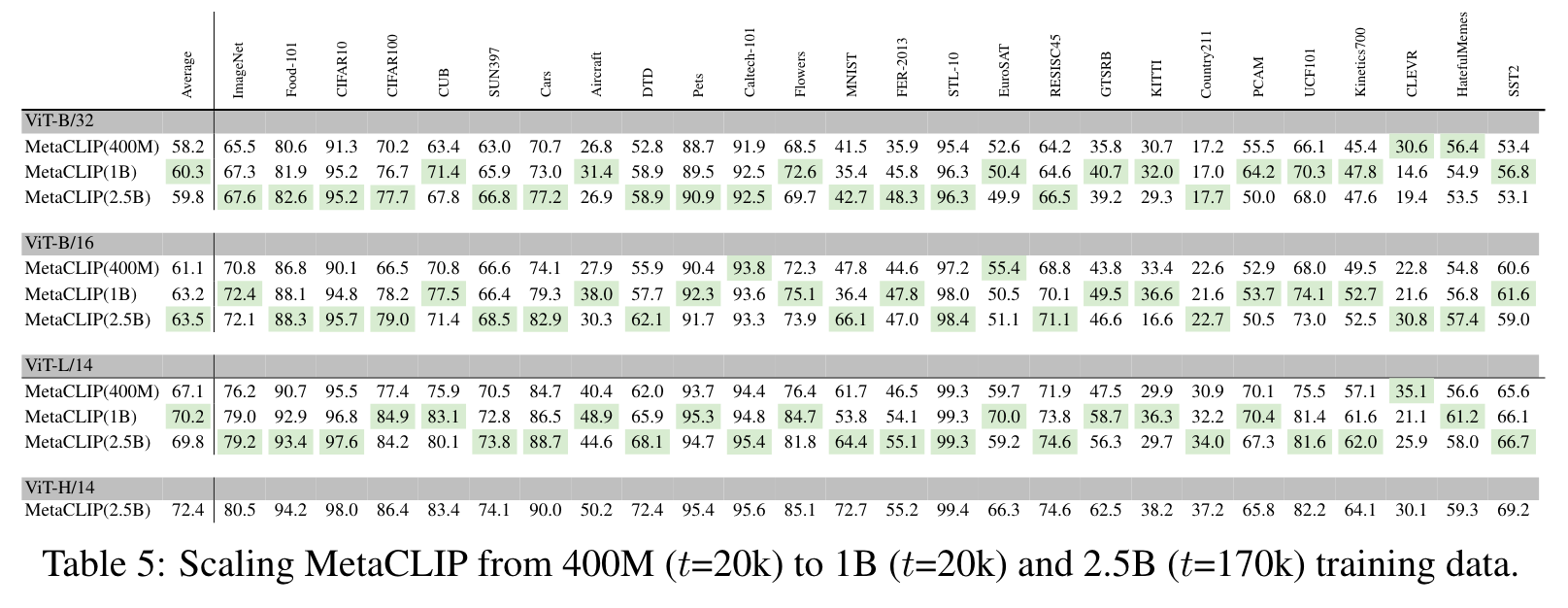

For balancing we consider 2 scenarios on this data: (i) t = 170k, which is resulting in 2.5B image- text pairs. This t = 170k configuration has tail counts amounting to 6% of the total counts, the same tail/head ratio that the 400M Pool 1 data has, produced by applying t = 20k on the 1.6B Pool 1 data. (ii) The t = 20k threshold applied to Pool 2 which results in 1B image-text pairs and compared to the 400M set from Pool 1 only increases tail metadata matches (head counts are capped at 20k). (p. 7)

ABLATION STUDY

We observe that the choice of t = 20k by CLIP yields the best performance for ImageNet and averaged accuracy and t = 15k or t = 35k are slightly worse. (p. 9)

To understand the key effect of balancing, we use the whole matched pool (1.6B image-text pairs) to train CLIP. Surprisingly, training on 4× more data (on head entries) significantly hurts the accuracy on ImageNet (61.9 vs 65.5) and averaged accuracy across 26 tasks (56.6 vs 58.2). (p. 9)

NEGATIVE RESULTS LEARNED FROM ABLATING CLIP CURATION

Self-curated Metadata

We initially attempted to build metadata directly from the text in raw image-text pairs (i.e., using terms appearing in text above a certain threshold of counts). We rank entries by count and keep the top 500,000. Metadata built this way appeared worse. We notice that although the top frequent entries are similar to CLIP’s metadata, the long-tailed part is very different (p. 15)

This approach results in worse quality metadata including low-quality spelling/writing (instead of high-quality entries from WordNet or Wikipedia). Further, the effect of balancing saturates earlier for such data (in a larger t, verified by CLIP training) since low-quality entries are also heavily in long-tail. (p. 15)

Cased WordNet

We also notice many cased words are missing from metadata (e.g., Word- Net is in lowercase). After adding cased WordNet into metadata, we notice a performance drop on ImageNet. The reason could be class names are more likely in lower case and upper case entry matching may reduce the written quality of texts. (p. 15)

Stopwords/Useless Entries Removal

We further study the effect of whether removing stopwords and useless words such as “photo” and “image” is beneficial. This led to al- most no difference since balancing entries reduced the effects of useless entries (each entry contributes to 0.0002% (1/500k) level of the total data points). To encourage a simplified solution, we do not intend to add more artificial filters. (p. 15)