Mobile V-MoEs Scaling Down Vision Transformers via Sparse Mixture-of-Experts

[mixture-of-experts multimodal deep-learning transformer This is my reading note for Mobile V-MoEs Scaling Down Vision Transformers via Sparse Mixture-of-Experts. This paper proposes a new mixture of experts to reduce the cost of vision transformer. There are two contributions, I) use image level instead of patch level mixture to reduce cost; 2) use super class based router to select experts so each expert could focus on a few related class.

Introduction

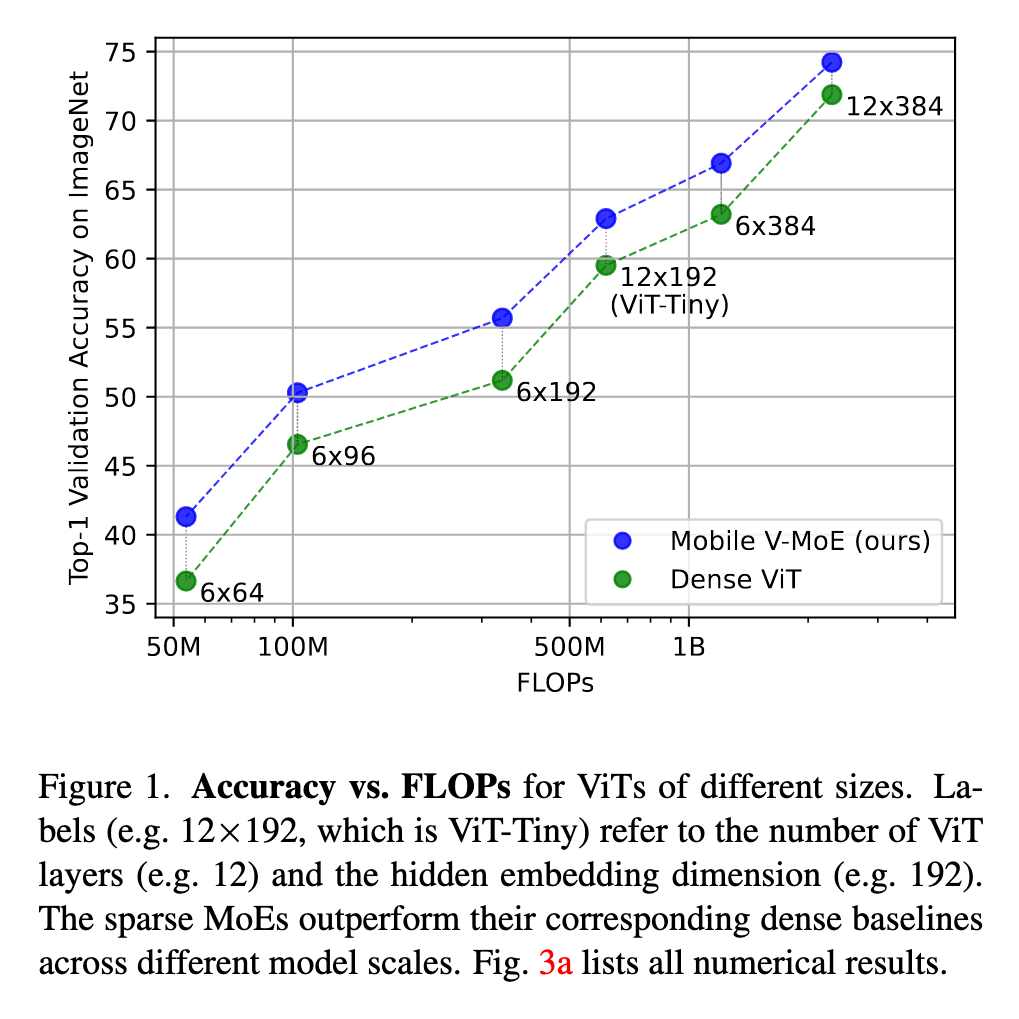

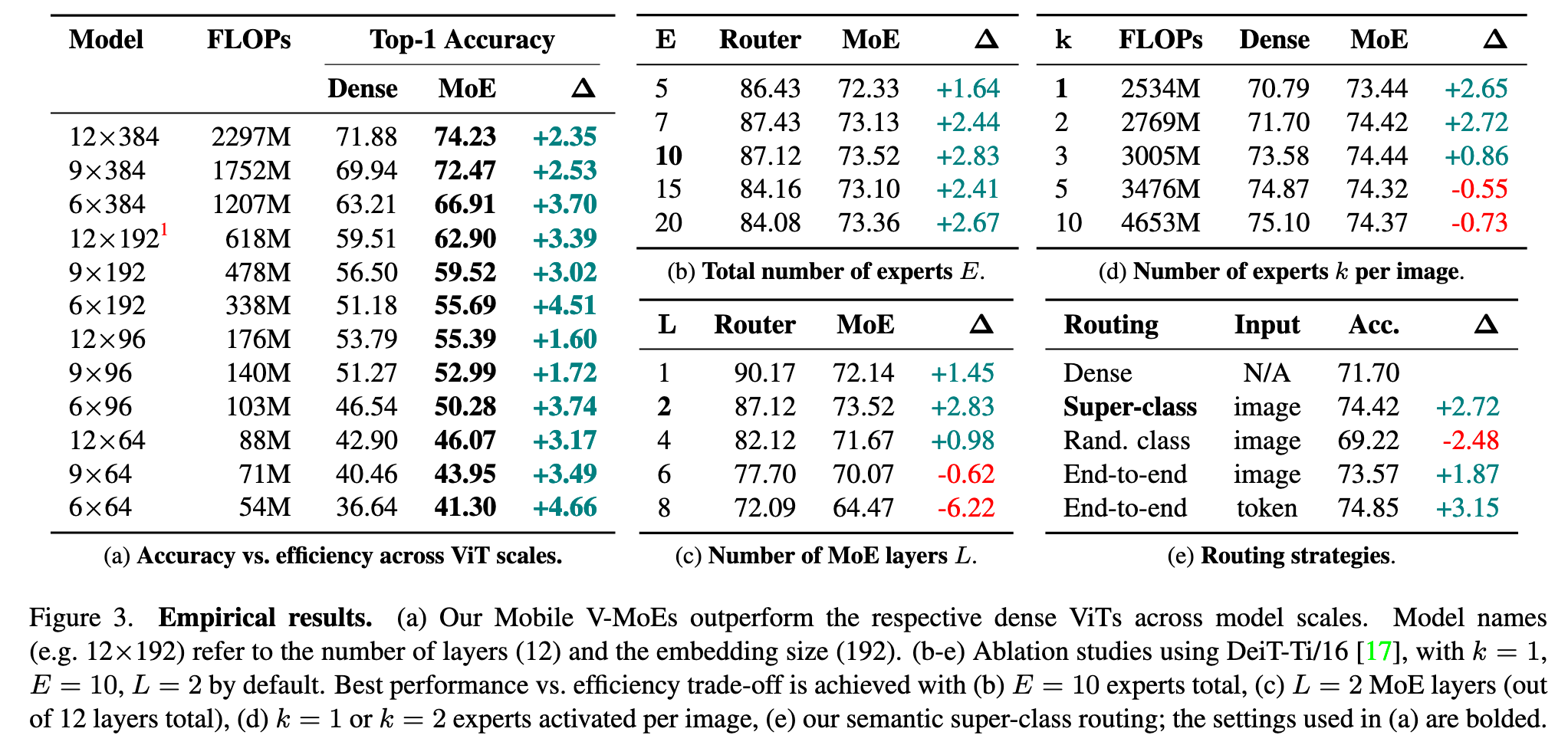

In this work, we instead explore the use of sparse MoEs to scale down Vision Transformers (ViTs) to make them more attractive for resource-constrained vision applications. To this end, we propose a simplified and mobile-friendly MoE design where entire images rather than individual patches are routed to the experts. We also propose a stable MoE training procedure that uses super-class information to guide the router. We empirically show that our sparse Mobile Vision MoEs (V-MoEs) can achieve a better trade-off between performance and efficiency than the corresponding dense ViTs. For example, for the ViT-Tiny model, our Mobile V-MoE outperforms its dense counterpart by 3.39% on ImageNet1k. For an even smaller ViT variant with only 54M FLOPs inference cost, our MoE achieves an improvement of 4.66%. (p. 1)

MoEs are NNs that are partitioned into “experts”, which are trained jointly with a router to specialize on subsets of the data. In MoEs, each input is processed by only a small subset of model parameters (aka conditional computation) (p. 1)

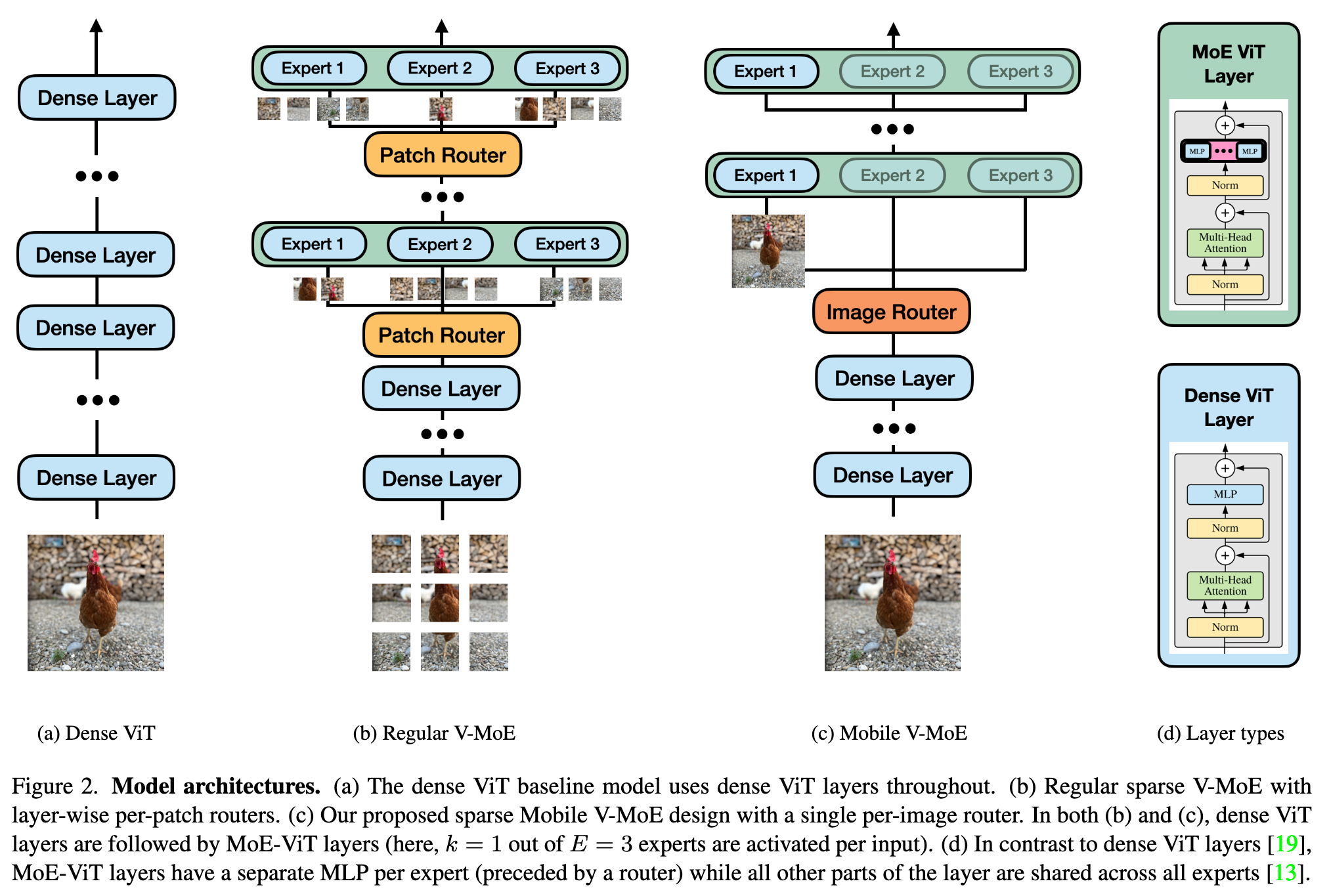

Sparse MoEs were popularized in deep learning by [16], which introduced sparse MoE-layers as drop-in replacements for standard NN layers. Most recent MoEs are based on the Transformer [19], which processes individual input tokens; in accordance, recent MoEs also route individual input tokens to experts, i.e., image patches in the case of Vision Transformers (ViTs) [2, 13] (see Fig. 2b). Conditional computation as implemented by sparse MoEs has enabled the training of Transformers of unprecedented size [4] (p. 1)

While Transformers are getting increasingly established as the de-facto standard architecture for large-scale visual modeling [2, 13], virtually all mobile friendly models still leverage convolutions due to their efficiency [1,5,6,11,15,18]. However, Transformer-based MoEs have not yet been explored for resource-constrained settings; this might be due to two main weaknesses of recently-popularized MoEs [16]. (p. 2)

Firstly, while per-token routing increases the flexibility to learn an optimal computation path through the model, it makes inference inefficient, as many (or even all) experts need to be loaded for a single input image. Secondly, recent MoEs train the routers jointly with the rest or the model in an end-to-end fashion. To avoid collapse to just a few experts while ignoring all others, one needs to use load balancing mechanisms [3] such as dedicated auxiliary losses [16]. However, the resulting complex optimization objectives often lead to training instabilities / divergence [4, 10, 12, 21]. (p. 2)

Scaling down ViTs via sparse MoEs

Conditional computation with sparse MoEs

An MoE implements conditional computation by activating different subsets of a NN (so-called experts) for different inputs. We consider an MoE layer with E experts as (p. 2)

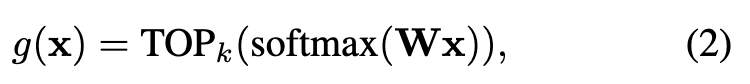

where x ∈ R^D is the input to the layer, e_i : R^D → R^D is the function computed by expert i, and g : R^D → R^E is the routing function which computes an input-dependent weight for each expert [16]. In a ViT-based MoE, each expert ei is parameterized by a separate multi-layer perceptron (MLP) within the ViT layer, while the other parts are shared across experts (see Fig. 2d). We use the routing function (p. 3)

Efficient and robust MoEs for small-scale ViTs

Per-image routing. Recent large-scale sparse MoEs use per-patch routing (i.e. the inputs x are individual image patches). This generally requires a larger number of experts to be activated for each image. For example, [13] show that in their MoE with per-patch routing, “most images use –on aggregate by pooling over all their patches– most of the experts” [13, Appendix E.3]. Thus, per-patch routing can increase the computational and memory overhead of the routing mechanism and reduce the overall model efficiency. We instead propose to use per-image routing (i.e., the inputs x are entire images) to reduce the number of activated experts per image, as also done in early works on MoEs [7, 9]. (p. 3)

Super-class-based routing. Previous works on sparse MoEs jointly train the router end-to-end together with the experts and the dense ViT backbone, to allow the model to learn the optimal assignment from inputs to experts based on the data [13]. While learning the optimal routing mechanism from scratch can result in improved performance, it often leads to training instabilities and expert collapse, where most inputs are routed to only a small subset of the experts, while all other experts get neglected during training [3]. Thus, an additional auxiliary loss is typically required to ensure load-balancing between the different experts, which can increase the complexity of the training process [3]. (p. 3)

In contrast, we propose to group the classes of the dataset into super-classes and explictly train the router to make each expert specialize on one super-class. To this end, we add an additional cross-entropy loss Lg between the router output g(x) in Eq. (2) and the ground truth super-class labels to the regular classification loss LC to obtain the overall weighted loss L = LC +λLg (we use λ = 0.3 in our experiments, which we found to work well). (p. 3)

If a dataset does not come with a super-class division, we can easily obtain one as follows: 1) we first train a dense baseline model on the dataset; 2) we then compute the model’s confusion matrix over a held-out validation set; 3) we finally construct a confusion graph from the confusion matrix and apply a graph clustering algorithm to obtain the super-class division [8]. This approach encourages the super-classes to contain semantically similar images that the model often confuses. Intuitively, by allowing the different MoE experts to specialize on the different semantic data clusters, performance on the highlyconfused classes should be improved. (p. 3)

Experiment and Ablation Study

Total number of experts

Fig. 3b shows that overall performance improves until E = 10, from which point onwards it stagnates. The router accuracy also drops beyond E = 10 due to the increased difficulty of the E-way super-classification problem. (p. 4)

Number of MoE layers

Fig. 3c shows that overall performance peaks at L = 2, and rapidly decreases for larger L. This is due to the router accuracy, which declines with increasing L as the router gets less information (from the 12 − L ViT layers). (p. 4)

Number of experts k per image

Fig. 3d shows that k = 1 and k = 2 perform best (relative to the dense baseline), with decreasing performance delta for larger k. (p. 4)

Routing strategies

Fig. 3e shows that our method (Fig. 2c) is better, except for learned per-token routing (as in the regular V-MoE [13], Fig. 2b), which however needs to activate many more experts and thus model parameters for each input image (up to 11.05M, vs. 6.31M for ours). (p. 4)