Multimodal Learning with Transformers A Survey

[token attention bert clip multimodal embedding deep-learning review transformer This is my reading note on Multimodal Learning with Transformers A Survey. This a paper provides a very nice overview of the transformer based multimodality learning techniques.

Introduction

Fundamentally, a multimodal AI system needs to ingest, interpret, and reason about multimodal information sources to realize similar human level perception abilities. Multimodal learning (MML) is a general approach to building AI models that can extract and relate information from multimodal data [1]. (p. 1)

Further, learning per-modal specificity and inter-modal (p. 1)

correlation can be simply realized by controlling the input pattern of self-attention. (p. 1)

Transformers are emerging as promising learners. VanillaTransformer [2] benefits from a self-attention mechanism, and is a breakthrough model for sequence-specific representation learning that was originally proposed for NLP, achieving the state-of-the-art on various NLP tasks. Following the great success of Vanilla Transformer, a lot of derivative models have been proposed, e.g., BERT [4], BART[87], GPT [88], Longformer [43], Transformer-XL [89], XLNet [90]. Transformers currently stand at the dominant position in NLP domains, and this motivates researchers try to apply Transformers to other modalities, such as visual domains. In early attempts for visual domain, the general pipeline is “CNN features + standard Transformer encoder”, and researchers achieved BERT-style pretraining, via preprocessing raw images by resizing to a low resolution and reshaping into a 1D sequence [91]. Vision Transformer (ViT) [5] is a seminal work that contributes an end-to-end solution by applying the encoder of Transformer to images. (p. 3)

Motivated by the great success of Transformer, VideoBERT [7] is a breakthrough work that is the first work to extend Transformer to the multimodal tasks. VideoBERT demonstrates the great potential of Transformer in multimodal context. Following VideoBERT, a lot of Transformer based multimodal pretraining models (e.g., ViLBERT [102],LXMERT [103], VisualBERT [104], VL-BERT [105], UNITER [106], CBT [107], Unicoder-VL [108], B2T2 [109], VLP [110], 12-in-1 [111], Oscar [112], Pixel-BERT [113], ActBERT [114], ImageBERT [115], HERO [116], UniVL [117]) have become research topics of increasing interest in the field of machine learning. (p. 3)

In 2021, CLIP [9] was proposed. It is a new milestone that uses multimodal pretraining to convert classification as a retrieval task that enables the pretrained models to tackle zero-shot recognition. Thus, CLIP is a successful practice that makes full use of large-scale multimodal pretraining (p. 3). to enable zero-shot learning. Recently, the idea of CLIP isfurther studied, e.g., CLIP pretrained model based zero-shot semantic segmentation [118], ALIGN [119], CLIP-TD [120], ALBEF [121], and CoCa [122]. (p. 3)

Vanilla Transformer

Vanilla self-attention (Transformer) can model it as a fully-connected graph in topological geometry space [158]. Compared with other deep networks (for instance, CNN is restricted in the aligned grid spaces/matrices), Transformers intrinsically have a more general and flexible modelling space. This is a notable advantage of Transformers for multimodal tasks. (p. 4)

Discussion There is an important unsolved problem that is post-normalization versus pre-normalization. The originalVanilla Transformer uses post-normalization for each MHSA and FFN sub-layer. However, if we consider this from the mathematical perspective, pre-normalization makes more sense [162]. This is similar to the basic principle of the theory of matrix, that normalization should be performed before projection, e.g., Gram–Schmidt process 2. This problem should be studied further by both theoretical research and experimental validation. (p. 4)

Tokenization

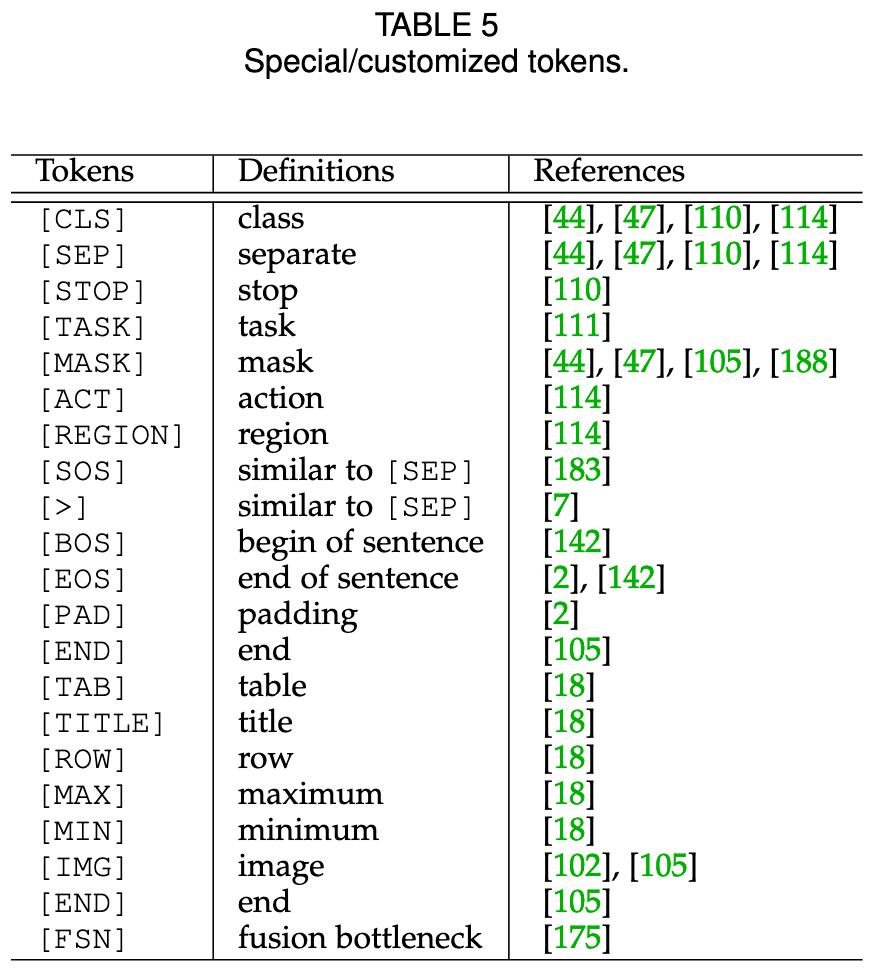

Special/Customized Tokens In Transformers, various special/customized tokens can be semantically defined asplace-holders in the token sequences, e.g., mask token[MASK] (p. 4)

Discussions:

- Tokenization is a more general approach from a geometrically topological perspective, achieved by minimizing constraints caused by different modalities. (p. 4)

- Tokenization is a more flexible approach to organize the input information via concatenation/stack, weightedsummation, etc. Vanilla Transformer injects temporal infor-mation to the token embedding by summing position embedding. (p. 4)

- Tokenization is compatible with the task-specificcustomized tokens, e.g., [MASK] token [4] for Masked Lan-guage Modelling, [CLASS] token [5] for classification. (p. 4)

Position Embedding

Position embeddings are added to the token embeddings to retain positional information [4].Vanilla Transformer uses sine and cosine functions to produce position embedding. To date, various implementations of position embedding have been proposed. (p. 4)

It can be understood as a kind of implicit coordinate basis of feature space, to provide temporal or spatial information to the Transformer. (p. 4). Furthermore, position embedding can be regarded as a kind of general additional information. (p. 4)

There is a comprehensive survey [166] discussing the position information in Transformers. For both sentence structures (sequential) and general graph structures (sparse, arbitrary, and irregular), position embeddings help Transformers to learn or encode the underlying structures. Considered from the mathematical perspective of self-attention, i.e., scaled dot-product attention, attentions are invariant to the positions of words (in text) or nodes (in graphs), if position embedding information is missing. Thus, in most cases, position embedding is necessary for Transformers. (p. 4)

Attention

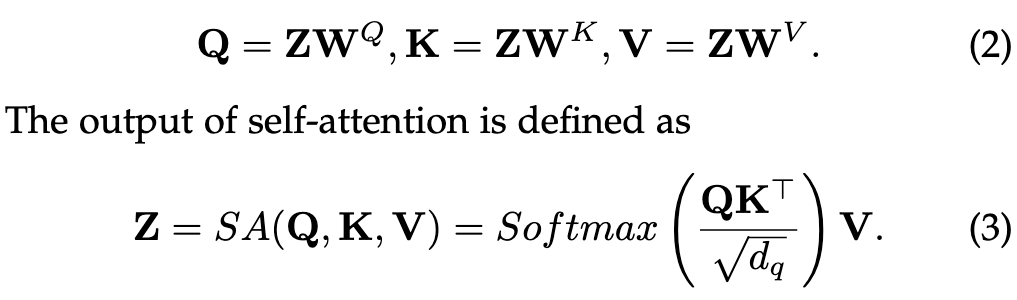

Self-Attention (SA) (p. 5) could be written as below:

the Transformer family has the non-local ability of global perception, similar to the NonLocal Network (p. 5)

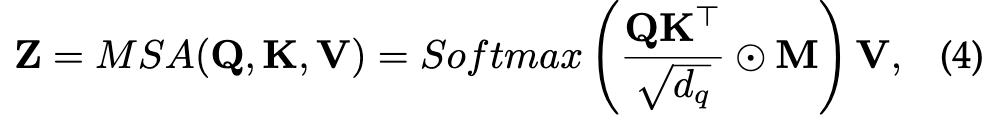

Masked Self-Attention (MSA) In practice, modification of self-attention is needed to help the decoder of Transformer to learn contextual dependence, to prevent positions from attending to subsequent positions (p. 5)

For instance, in GPT [88],an upper triangular mask to enable look-ahead attention where each token can only look at the past tokens. Masking can be used in both encoder [163], [168] and decoder ofTransformer, and has flexible implementations, e.g., 0-1 hardmask [163], soft mask [168]. (p. 5)

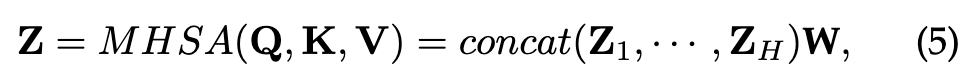

Multi-Head Self-Attention (MHSA) (p. 5) could be written as:

The idea of MHSA is a kind of ensemble. MHSA helps the model to jointly attend to information from multiple representation sub-spaces. (p. 5)

Multimodality Transformer

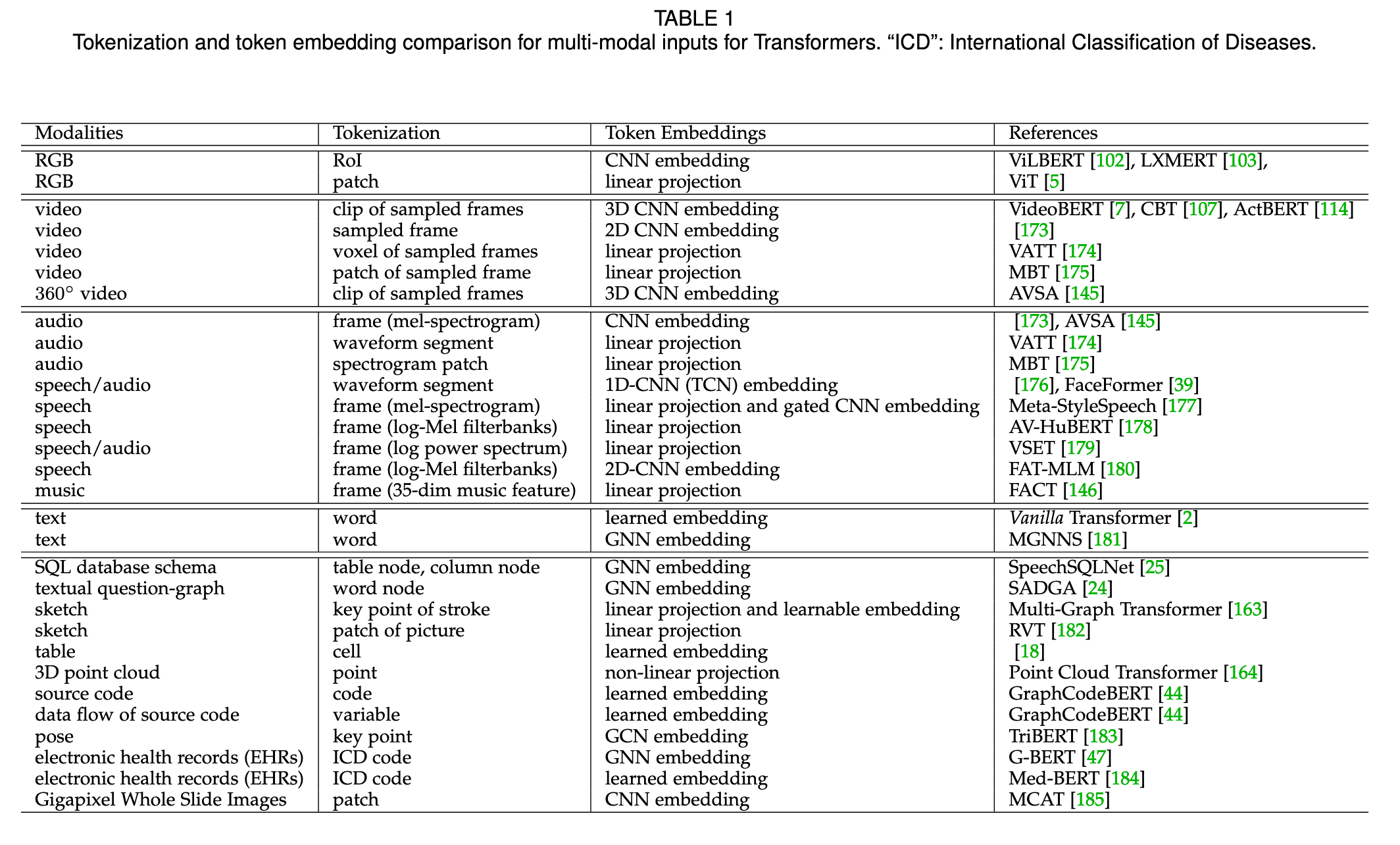

Tokenization and Embedding Processing Given an input from an arbitrary modality, users only need to perform two main steps, (1) tokenize the input, and (2) select an embedding space to represent the tokens, before inputting the data into Transformers. In practice, both the tokenizing input and selecting embedding for the token are vital for Transformers but highly flexible, with many alternatives. (p. 5)

Token Embedding Fusion In practice, Transformers allow each token position to contain multiple embeddings. This is essentially a kind of early-fusion of embeddings (p. 6). The most common fusion is the token-wise summing of themultiple embeddings, e.g., a specific token embedding ⊕position embedding. (p. 6)

Cross Modality Interactions

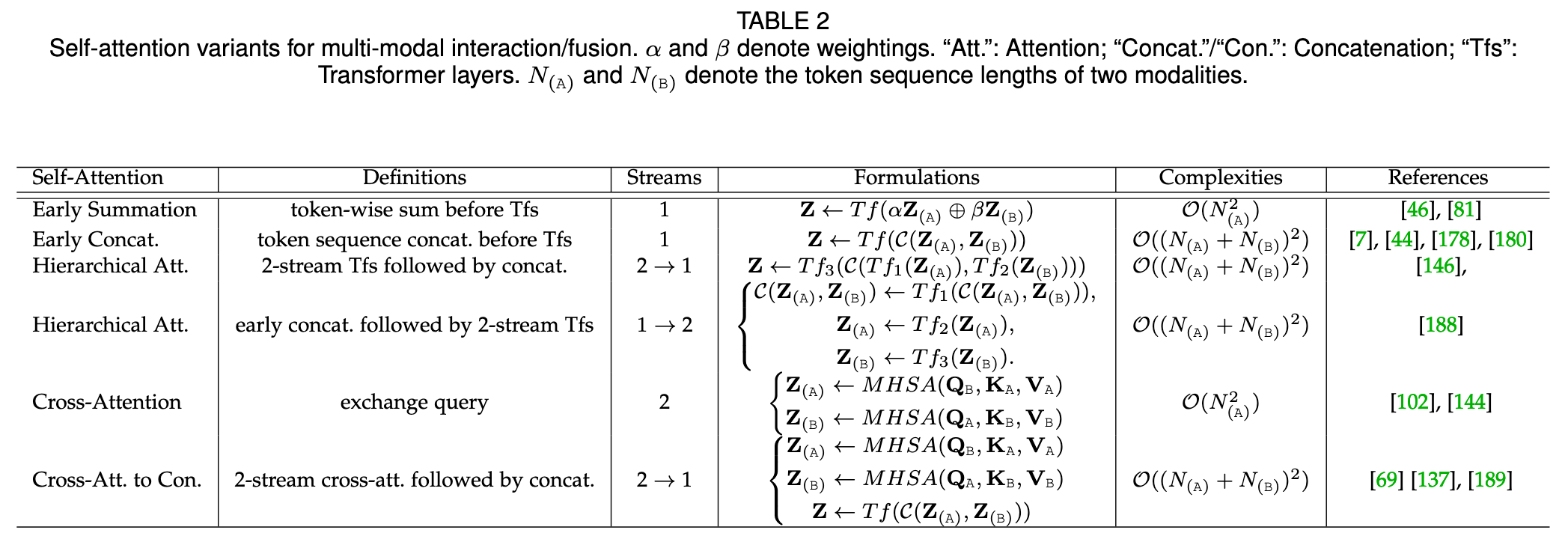

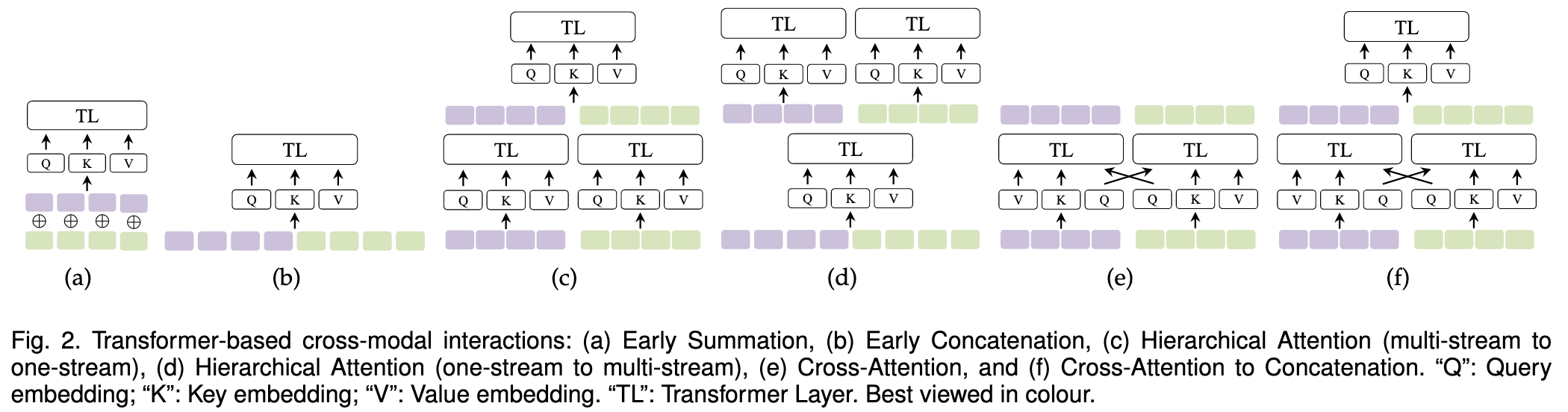

In multimodal Transformers, cross-modal interactions (e.g.,fusion, alignment) are essentially processed by self-attention and its variants. (p. 6)

- Early summation. Its main advantage is that it does not increase computational complexity. However, its main disadvantage is due to the manually set weightings. (p. 7)

- Early concatenation. However, the longer sequence after concatenation will increase computational complexity. Early concatenation is also termed “all-attention” or “CoTransformer” (p. 7)

- Hierarchical attention. This method perceives the cross-modal interactions and meanwhile preserves the independence of uni-modal representation. (p. 7)

- Cross-attention. Cross-attention attends to each modality conditioned on the other and does not cause higher computational complexity, however if considered for each modality, this method fails to perform cross-modal attention globally and thus loses (p. 7) the whole context. As discussed in [188], two-stream crossattention can learn cross-modal interaction, whereas there is no self-attention to the self-context inside each modality. (p. 8)

Transformers for Multimodal Pretraining

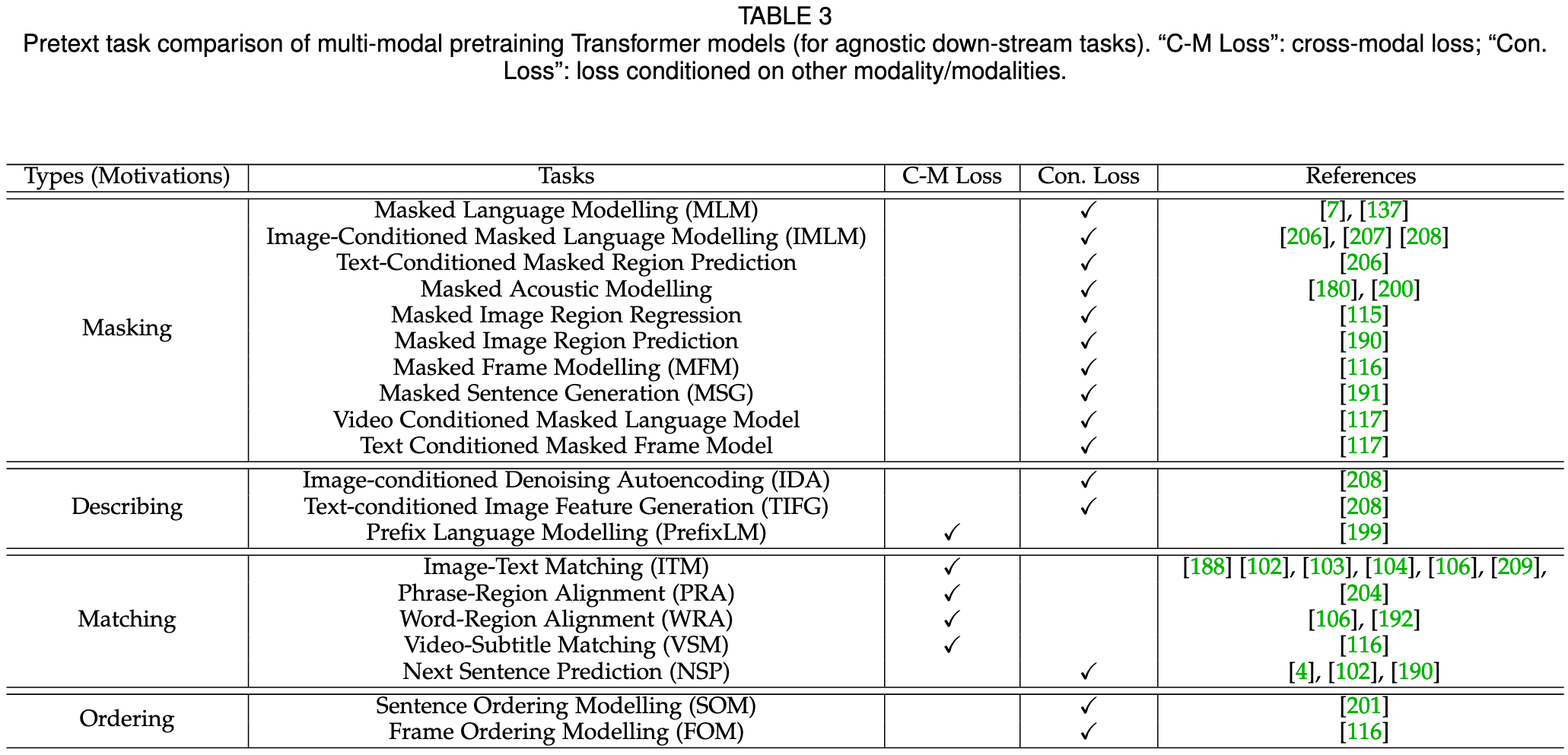

Task-Agnostic Multimodal Pretraining

Among existing work, the following main trends are emerging:

- Vision-language pretraining (VLP) is a major research problem in this field. VLP is including both “image + language” and “video + language”, also termed visual-linguistic pretraining. (p. 9)

- Speech can be used as text. Thanks to recent advances in automatic speech recognition (ASR) techniques, in a multimodal context, speech can be converted to text by the off the-shelf speech recognition tools. (p. 9)

- (3) Overly dependent on the well-aligned multimodal data. A majority of Transformer-based multimodal pretraining works in a self-supervised manner, however, it is overly dependent on the well-aligned multimodal sample pairs/tuples. (p. 9)

- (4) Most of the existing pretext tasks transfer well across modalities. For instance, Masked Language Modelling (MLM) in the text domain has been applied to audio and image, (p. 9)

Discussion: How to look for more corpora that intrinsically have well-aligned cross-modal supervision, such as instructional videos, is still an open problem. However, weaklyaligned cross-modal samples are popular in the real-life scenarios, for instance, enormous weakly aligned multimodal data samples are emerging in e-commerce [137], due to fine-grained categories, complex combinations, and fuzzy correspondence. (p. 9)

Discussion: In spite of the recent advances, multimodal pretraining Transformer methods still have some obvious bottlenecks. For instance, as discussed by [208] in VLP field, while the BERT-style cross-modal pretraining models produce excellent results on various down-stream visionlanguage tasks, they fail to be applied to generative tasks directly. As discussed in [208], both VideoBERT [7] and CBT [107] have to train a separate video-to-text decoder for video captioning. This is a significant gap between the pretraining models designed for discriminative and generative tasks, as the main reason is discriminative task oriented pretraining models do not involve the decoders of Transformer. Therefore, how to design more unified pipelines that can work for both discriminative and generative down-stream tasks is also an open problem to be solved. Again for instance, common multimodal pretraining models often underperform for fine-grained/instance-level tasks as discussed by [137]. (p. 10)

Discussion How to boost the performance for multimodal pretraining Transformers is an open problem. Some practices demonstrate that multi-task training (by adding auxiliary loss) [111], [137] and adversarial training [210] improve multimodal pretraining Transformers to further boost the performance. Meanwhile, overly compound pretraining objectives potentially upgrade the challenge of balancing among different loss terms, thus complicate the training optimization [199] (p. 10)

Task-Specific Multimodal Pretraining

In practices of multimodal Transformers, the aforementioned down-stream task -agnostic pretraining is optional, not necessary, and down-stream task specific pretraining is also widely studied [150], [190], [208], [211]. The main reasons include: (1) Limited by the existing technique, it is extremely difficult to design a set of highly universal network architectures, pretext tasks, and corpora that work for all the various down-stream applications. (2) There are nonnegligible gaps among various down-stream applications,e.g., task logic, data form, making it difficult to transfer frompretraining to down-stream applications. (p. 10)

CHALLENGES AND DESIGNS

Fusion

We note that the simple prediction-based late fusion [247], [248] is less adopted in MML Transformers. This makes sense considering the motivations of learning stronger multimodal contextual representations and great advance of computing power. For enhancing and interpreting the fusion of MML, probing the interaction and measuring the fusion between modalities [249] would be an interesting direction to explore. (p. 12)

Alignment

A representative practice is to map two modalities into a common representation space with contrastive learning over paired samples. The models based on this idea are often enormous in size and expensive to optimize from millions or billions of training data. Consequently, successive works mostly exploit pretrained models for tackling various downstream tasks [120], [263], [264], [265], [266]. These alignment models have the ability of zero-shot transfer particularly for image classification via prompt engineering [267]. This novel perspective is mind-blowing, given that image classification is conventionally regarded as a unimodal learning problem and zero-shot classification remains an unsolved challenge despite extensive research (p. 12)

Finegrained alignment will however incur more computational costs from explicit region detection and how to eliminate this whilst keeping the region-level learning capability becomes a challenge. (p. 12)

Transferability

Transferability is a major challenge for Transformer based multimodal learning, involving the question of how to transfer models across different datasets and applications. (p. 12)

Data augmentation and adversarial perturbation strategies help multimodal Transformers to improve the generalization ability. VILLA [210] is a two-stage strategy (taskagnostic adversarial pretraining, followed by task-specific adversarial finetuning) that improves VLP Transformers. (p. 12)

The main inspiration that CLIP presents the community is that the pretrained multimodal (image and text) knowledge can be transferred to down-stream zero-shot image prediction by using a prompt template “Aphoto of a {label}.” to bridge the distribution gap between training and test datasets. (p. 12)

Over-fitting is a major obstacle to transfer. Multimodal Transformers can be overly fitted to the dataset biases during training, due to the large modelling capability. (p. 12)

Efficiency

Multimodal Transformers suffer from two major efficiency issues: (1) Due to the large model parameter capacity, they are data hungry and thus dependent on huge scale training datasets. (2) They are limited by the time and memory complexities that grow quadratically with the input sequence length, which are caused by the self-attention. (p. 12). Possible solutions could be:

- Knowledge distillation. (p. 13)

- Simplifying and compressing model. (p. 13)

- Asymmetrical network structures. Assign different model capacities and computational size properly for different modalities, to save parameters (p. 13)

- Improving utilization of training samples. Liu et al. [281] train a simplified LXMERT by making full use of fewer samples at different granularities. Li et al. [282]use fewer data to train CLIP by fully mining the potential self-supervised signals of (a) self-supervision within each modality, (b) multi-view supervision across modalities, and (c) nearest-neighbour supervision from other similar pairs. (p. 13)

- Compressing and pruning model. (p. 13)

- Optimizing the complexity of self-attention. Transformers cost time and memory that grows quadratically with the input sequence length (p. 13). Sparse factorizations of the attention matrix to reduce the quadratical complexity to O(n√n), (p. 13)

- Optimizing the complexity of self-attention based multimodal interaction/fusion. (p. 13)

Universalness

The currently unifying-oriented attempts mainly include:

- Unifying the pipelines for both uni-modal and multimodal inputs/tasks. (p. 13)

- Unifying the pipelines for both multimodal understanding and generation. In general, for multimodal Transformer pipelines, understanding and discriminative tasks require Transformer encoders only, while generation/generative tasks require both Transformer encoders and decoders. Existing attempts use multi-task learning to combine the understanding and generation workflows, where two kinds of workflows are jointly trained by multitask loss functions. From the perspective of model structures, typical solutions include: (a) encoder + decoder,e.g., E2E-VLP [271]. (b) separate encoders + cross encoder + decoder, e.g., UniVL [117], CBT [107]. (c) single unified/combined encoder-decoder, e.g., VLP [110]. (d) two-stream decoupled design [191]. (p. 14)

- Unifying and converting the tasks themselves, e.g.,CLIP [9] converts zero-shot recognition to retrieval, thus reduces the costs of modifying the model. (p. 14)

DISCUSSION AND OUTLOOK

Furthermore, a clear gap remains between the state-of-the-art and this ultimate goal. In general, existing multimodal Transformer models [9], [199], [263] are superior only for specific MML tasks (p. 14).