OmnimatteRF Robust Omnimatte with 3D Background Modeling

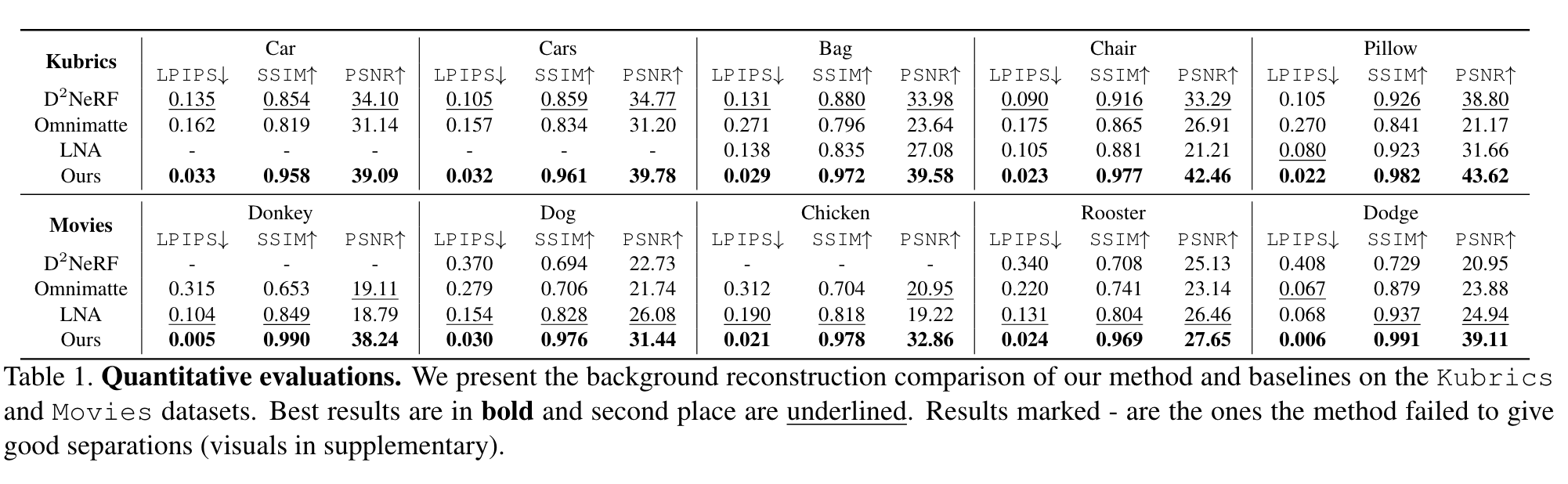

[video-inpainting matte nerf d2nerf omnimatte deep-learning 3d This is my reading note on OmnimatteRF: Robust Omnimatte with 3D Background Modeling. The paper proposes a method for video matting. It models the background as a 3D nerf and each foreground object as 2D image

Introduction

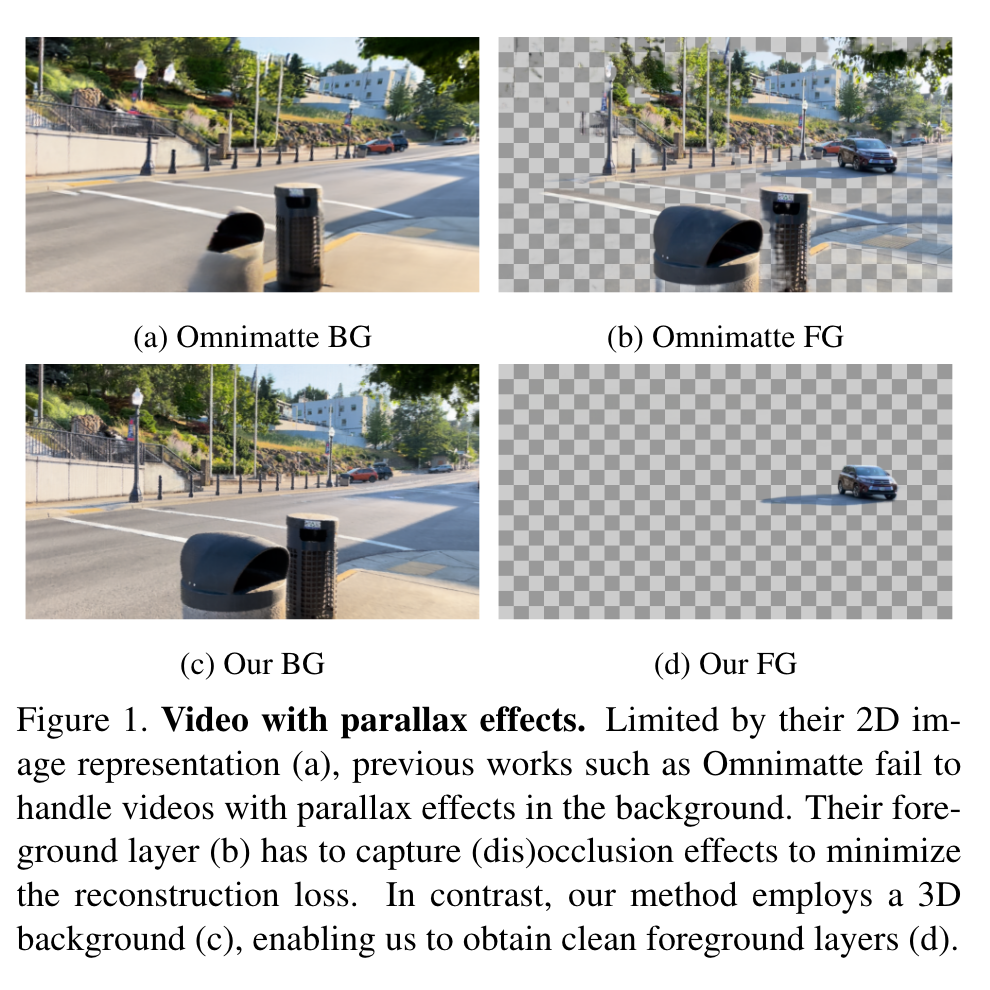

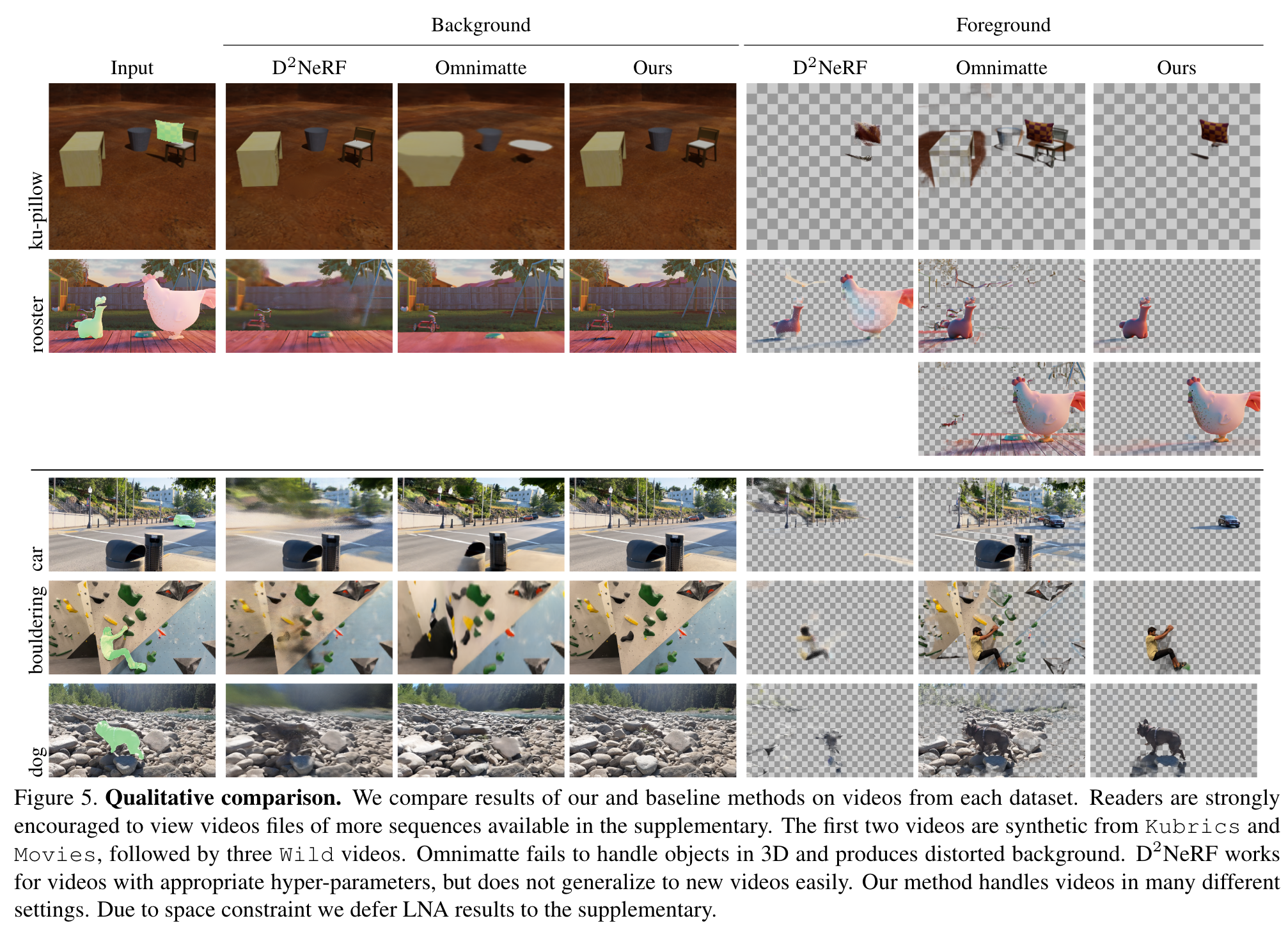

Video matting is the problem of separating a video into multiple layers with associated alpha mattes such that the layers are composited back to the original video. Methods like Omnimatte have been proposed to separate dynamic foreground objects of interest into their own layers. However, prior works represent video backgrounds as 2D image layers, limiting their capacity to express more complicated scenes, thus hindering application to real-world videos. In this paper, we propose a novel video matting method, OmnimatteRF, that combines dynamic 2D foreground layers and a 3D background model. The 2D layers preserve the details of the subjects, while the 3D background robustly reconstructs scenes in real-world videos. (p. 1)

We propose a method that has the benefit of both by combining 2D foreground layers with a 3D background model. The lightweight 2D foreground layers can represent multiple object layers, including complicated objects, motions, and effects that may be challenging to be modeled in 3D. At the same time, modeling background in 3D enables handling background of complex geometry and non-rotational camera motions, allowing for processing a broader set of videos than 2D methods. We call this method OmnimatteRF and show in experiments that it works robustly on various videos without per-video parameter tuning. (p. 2)

Related Work

The most promising attempt to tackle this problem is Omnimatte [21]. Omnimattes are RGBA layers that capture dynamic foreground objects and their associated effects. Given a video and one or more coarse mask videos, each corresponding to a foreground object of interest, the method reconstructs an omnimatte for each object, in addition to a static background that is free from all of the objects of interest and their associated effects. While Omnimatte [21] works well for many videos, it is limited by its use of homography to model backgrounds, which requires the background be planar or the video contains only rotational motion. This is not the case as long as there exists parallax caused by camera motions and objects occlude each other. This limitation hinders its application in many real-world videos, as shown in Fig. 1 (p. 1)

D2NeRF [36] attempts to address this issue using two radiance fields, which model the dynamic and static part of the scene. The method works entirely in 3D and can handle complicated scenes with significant camera motion. It is also self-supervised in the sense that no mask input is necessary. However, it separates all moving objects from a static background and it is not clear how to incorporate 2D guidance defined on video such as rough masks. Further, it cannot independently model multiple foreground objects. A simple solution of modeling each foreground object with a separate radiance field could lead to excessive training time, yet it is not clear how motions could be separated meaningfully in each radiance field. (p. 2)

Proposed Method

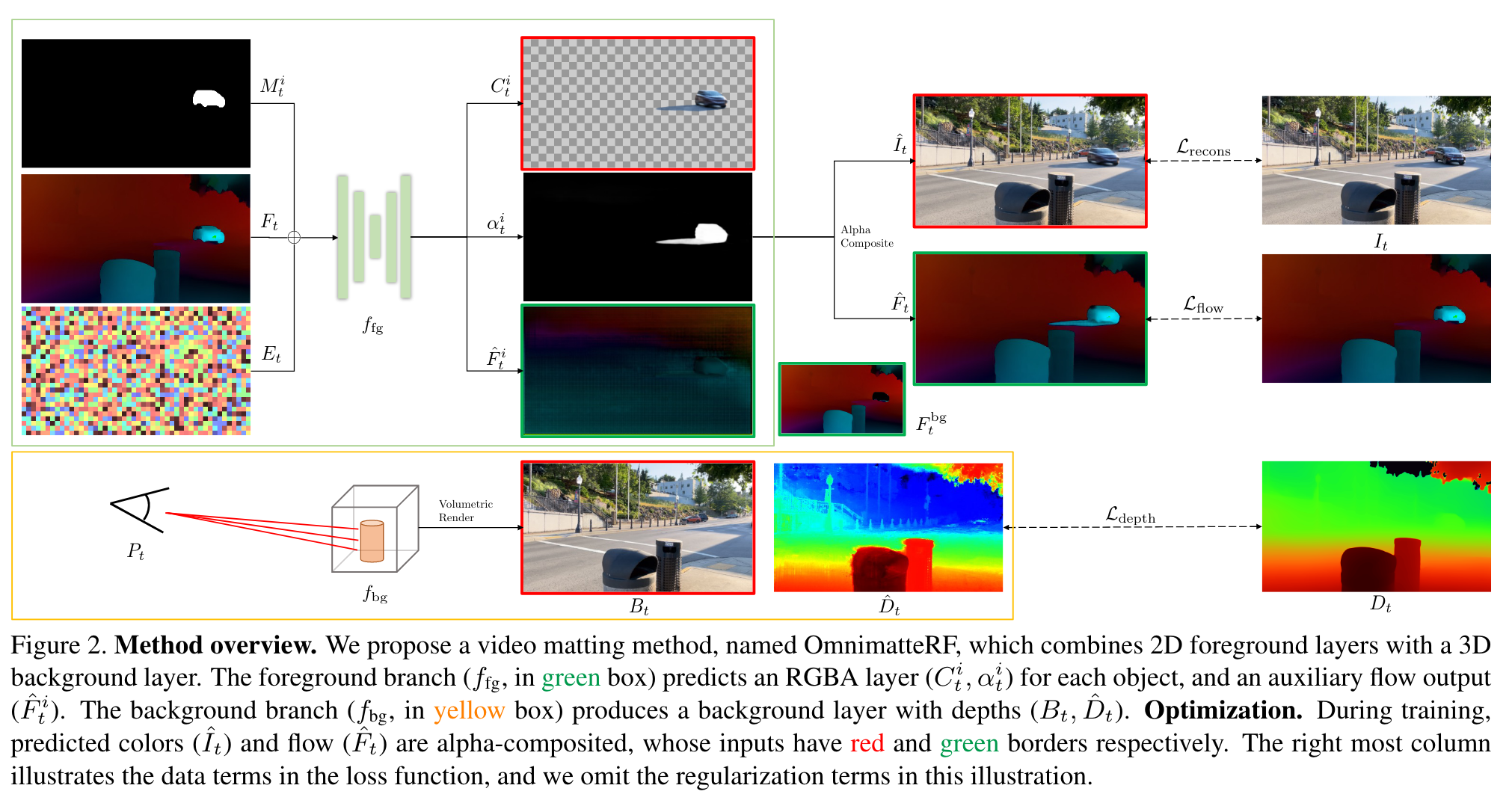

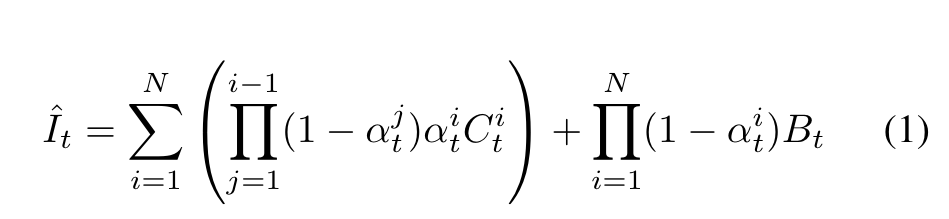

In the matting setup, the user prepares a video of T frames ${I_t}^T_{t=1}$, and N ordered mask layers ${M^i_t }^N_{i=1}$, each containing a coarse mask video of an object of interest. The video’s camera parameters are also precomputed as {Pt}. (p. 3)

The goal is to predict RGBA foreground layers Ci t and αi t that contain the objects together with their associated effects, and a background layer Bt which is clean and free from the effects cast by the foreground objects. An input frame It should be reconstructed by alpha compositing the foreground layers above the background. (p. 3)

In Omnimatte, the background is represented by a static 2D image and a homography transform Pt. To compose a frame, part of the static background is extracted according to the estimated homography Pt. The key idea of our work is to represent the static background in 3D using a radiance field, while keeping the foreground in 2D to better capture the dynamics of objects. We employ an explicit factorized voxel-based radiance field [8] to model the background. In this case, Pt represents a camera pose, and a background frame is rendered with volume rendering (p. 3)

The OmnimatteRF Model

For any given frame, the foreground branch predicts an RGBA image (omnimatte) for each object, and the background branch renders a single RGB image. (p. 3)

Preprocessing. Following similar works, we use an offthe-shelf model RAFT [29] to predict optical flow between neighboring frames. The flow is used as an auxiliary input and ground truth for supervision, denoted by {Ft}. We also use an off-the-shelf depth estimator MiDaS [26] to predict monocular depth maps {Dt} for each frame and use them as ground truth for the monocular depth loss. (p. 3)

Foreground. The foreground branch is a UNet-style convolutional neural network, ffg, similar to that of Omnimatte. The input of the network is a concatenation of three maps:

- The coarse mask Mi t . The mask is provided by the user, outlining the object of interest. Mask values are ones if the pixels are inside the object.

- The optical flow Ft. It provides the network with motion hints. Note that the network also predicts an optical flow as an auxiliary task (detailed in Sec. 3.2.2).

- The feature map Et. Each pixel (x, y) in the feature map is the positional encoding of the 3-tuple (x, y, t). Multiple foreground layers are processed individually. For the i-th layer, the network predicts the omnimatte layer (Ci t , αi t) and the flow Fˆi t . (p. 3)

Optimizing the Model

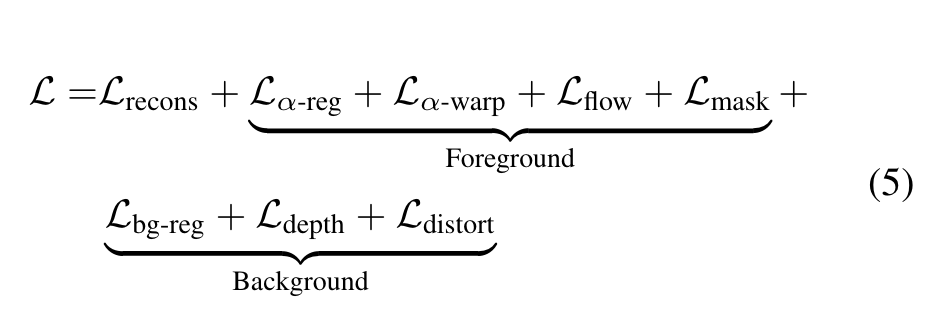

We optimize an OmnimatteRF model for every video since both branches of our model are video-specific. To supervise learning, we employ an image reconstruction loss and several regularization losses. (p. 3)

Reconstruction Loss

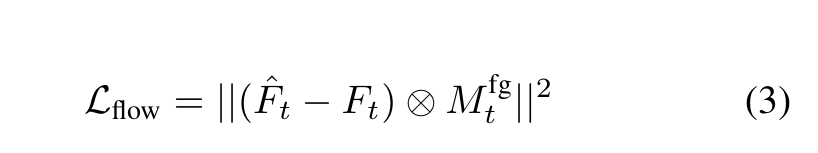

Foreground Losses

We follow Omnimatte and include the alpha regularization loss Lα-reg, alpha warp loss Lα-warp, and flow reconstruction loss Lflow. We also bootstrap the initial alpha prediction to match the input mask with the mask loss Lmask, which is gradually decayed and disabled once its value drops below the threshold. (p. 4)

Instead, we use the ground truth flow Ft as network input to provide motion cues and a masked version of Ft as background flow for composition. The masked flow is F mt = Ft ⊗ (1 − Mfg t ), which is the ground truth optical flow with the regions marked in the coarse masks set to zeros. ⊗ denotes elementwise multiplication. We find it crucial to use F mt rather than Ft for composition, as the latter case encourages the network to produce empty layers with αi t equal to zero everywhere. (p. 4)

Background Losses

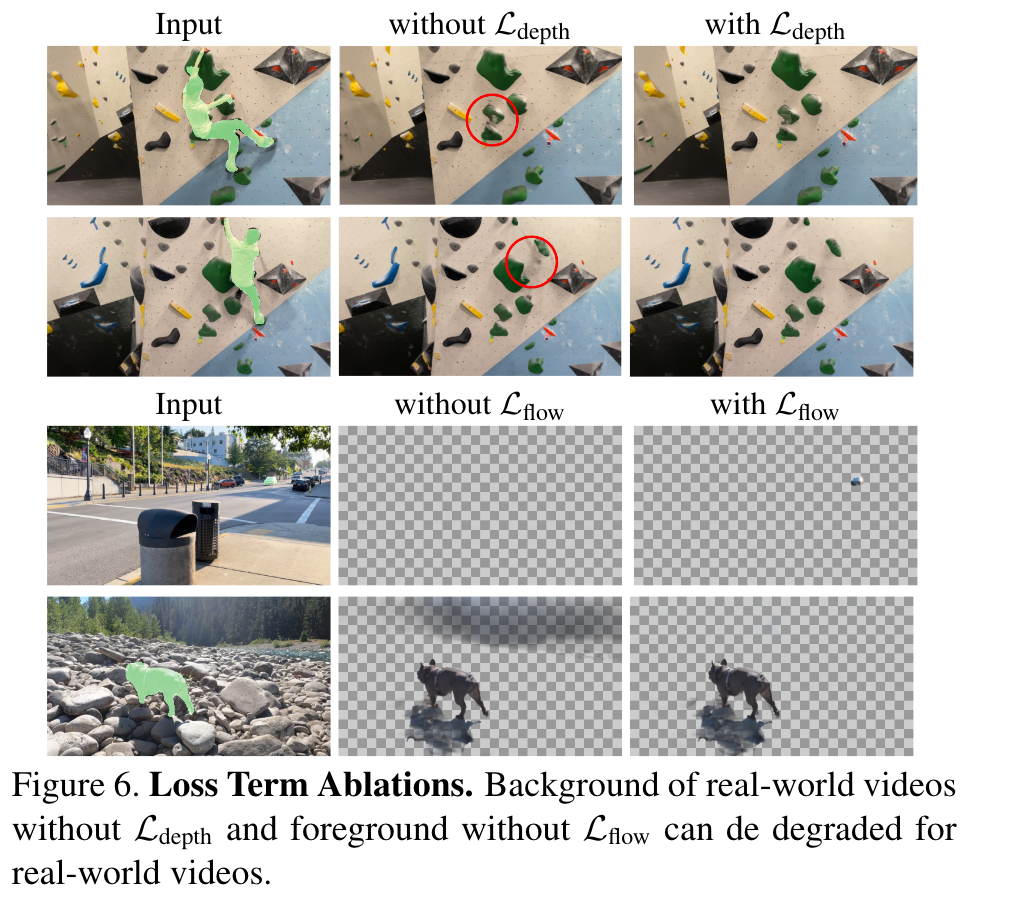

Apart from the reconstruction loss, the background network is supervised by the total variation regularization loss, Lbg-reg, as in TensoRF [8]. In addition, monocular depth supervision is used to improve scene reconstruction when the camera motions consist of rotation only: (p. 5)

Also, we empirically find that Ldepth can introduce floaters, and employ the distortion loss Ldistort proposed in Mip-NeRF 360 [4] to reduce artifacts in the background. (p. 5)

Summary

At every optimization step, Lrecons and background losses are evaluated at sparse random locations. Foreground losses are computed for the full image. (p. 5)

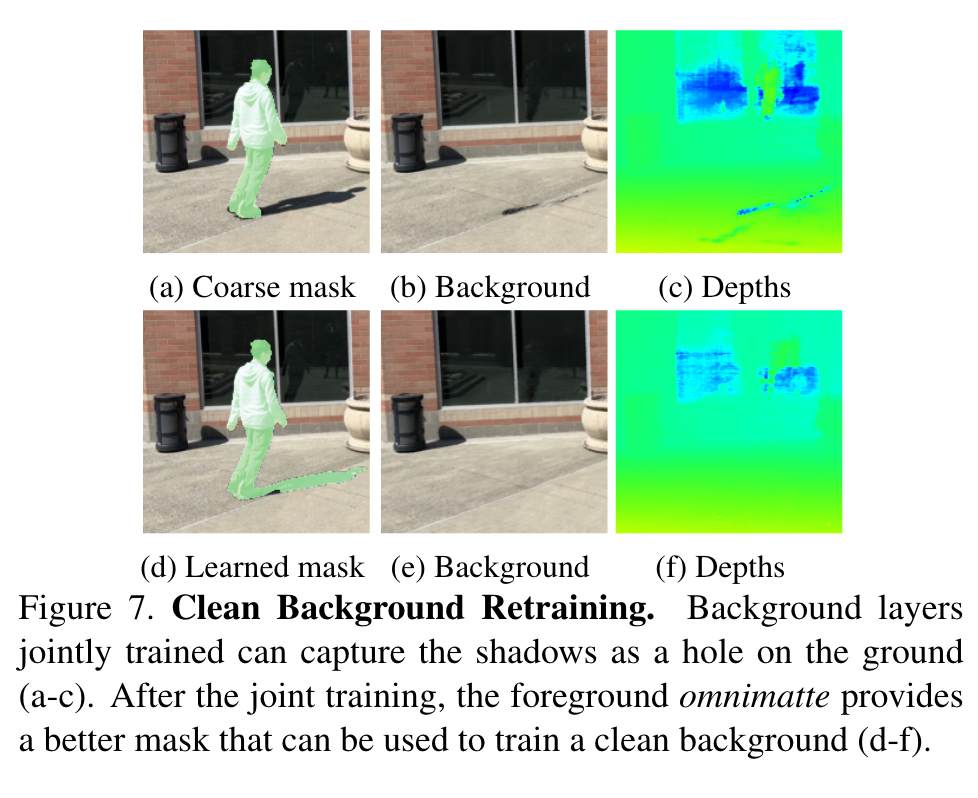

Clean Background via Masked Retraining

When the pipeline is trained jointly as described above, it is sometimes observed that the background radiance field models some of the foreground contents like shadows (see Fig. 3(c)). Compared to 2D images, 3D radiance fields are so much more capable that they can exploit distorted geometry constructs, such as holes and floaters, to capture some temporal effects, although the models are given no time information. (p. 5)

Therefore, we propose to obtain clean background reconstruction via an optional optimization step. In joint training, the foreground omnimatte layers can capture most associated effects, including the parts with leaked content in the background layer. The alpha layers αt can then be used to train a radiance field model from scratch, with no samples from the foreground region where alpha values are high. (p. 5)

Experiment

Limitations

We list some limitations that future works can explore.

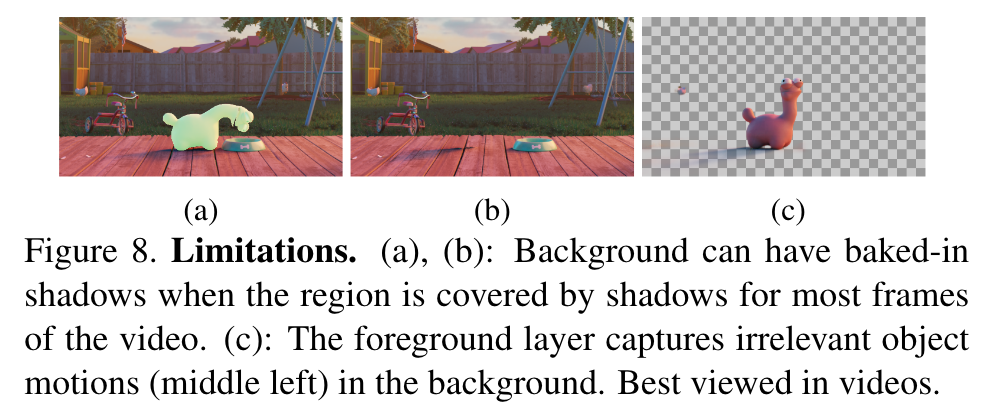

- If a background region is covered by shadows nearly all of the time, the background model cannot recover its color correctly. An example from a Movies video is shown in Fig. 8. In theory, an omnimatte layer has an alpha channel and can capture only the additive shadow that allows the background to have the original color. However, this problem is largely underconstrained in the current setting, making it ambiguous and leading the background to unsatisfying solutions.

- The foreground layer captures irrelevant content. In real-world videos, unrelated motions often exist in the background, like swaying trees and moving cars. These effects cannot be modeled by the static radiance field and will be captured by the foreground layer regardless of their association with the object. Possible directions include i) using a dummy 2D layer to catch such content or ii) a deformable 3D background model with additional regularization to address the ambiguity as both background and foreground can model motion.

- Foreground objects may have missing parts in the omnimatte layers if they’re occluded. Since our foreground network predicts pixel values for alpha composition, it does not always hallucinate the occluded parts.

- The video resolution is limited. This is primarily due to the U-Net architecture of the foreground model inherited from Omnimatte. Higher resolutions can potentially be supported with the use of other lightweight image encoders.

- The foreground layer may capture different content when the weights are randomly initialized differently. We include visual results in the supplementary materials. (p. 7)