Scaling Vision Transformers

[multimodal half-precision vit network-architecture-search deep-learning review adam transformer weight-decay adafactor This is my reading note for Scaling Vision Transformers. This paper provides a detailed comparison and study of designing vision transformer.

Introduction

Optimal scaling of Transformers in NLP was carefully studied in [22], with the main conclusion that large models not only perform better, but do use large computational budgets more efficiently. (p. 1)

Specifically, we discover that very strong L2 regularization, applied to the final linear prediction layer only, results in a learned visual representation that has very strong few-shot transfer capabilities (p. 1)

Core Results

Scaling up compute, model and data together

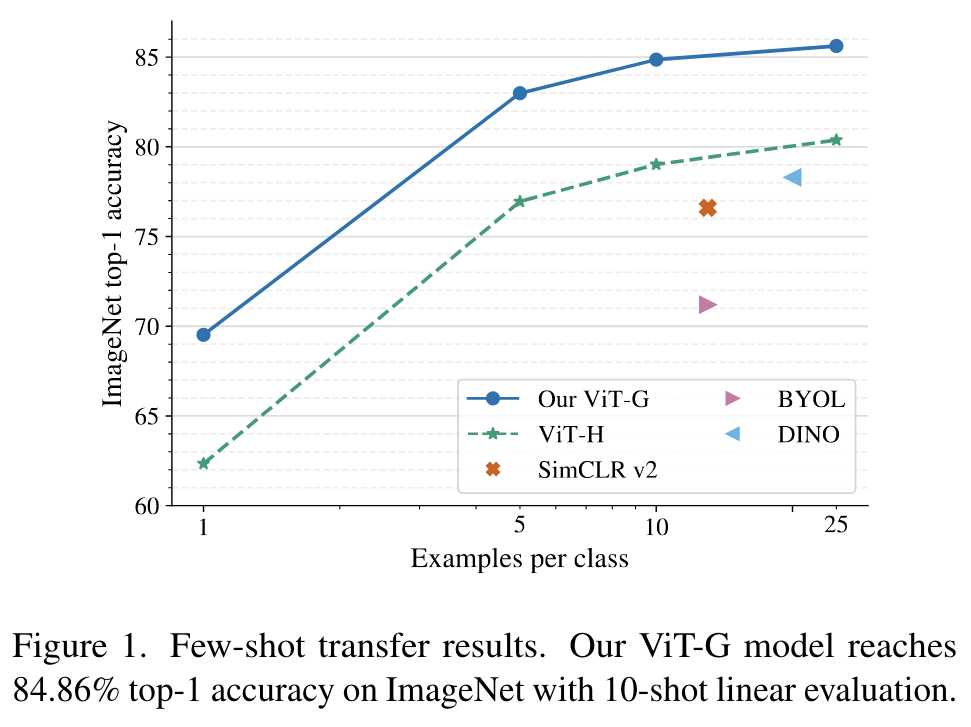

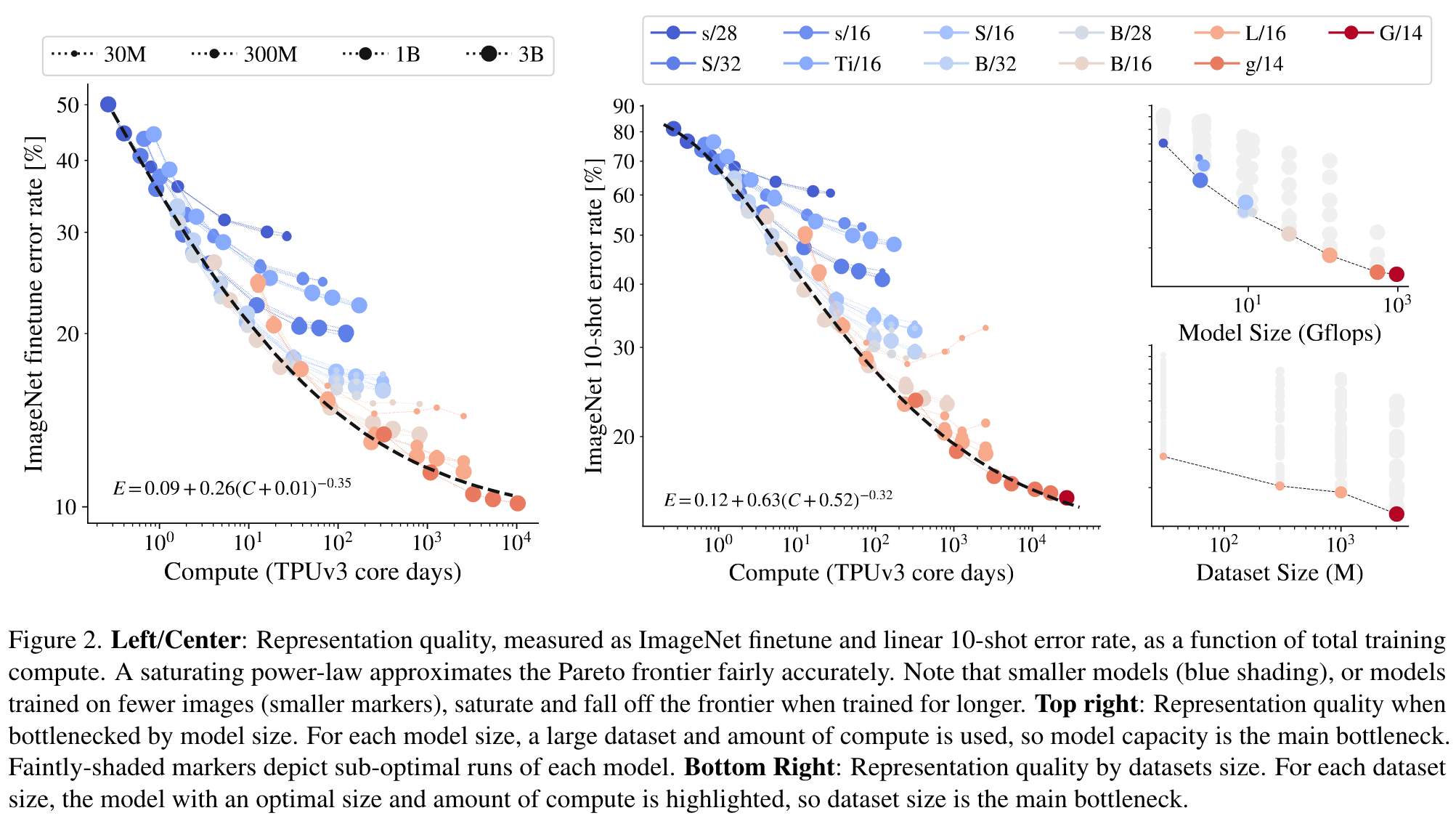

- First, scaling up compute, model and data together improves representation quality. However, it appears that at the largest size the models starts to saturate, and fall behind the power law frontier (linear relationship on the log-log plot in Figure 2). (p. 2)

- Second, representation quality can be bottlenecked by model size. (p. 2)

- Third, large models benefit from additional data, even beyond 1B images. When scaling up the model size, the representation quality can be limited by smaller datasets; even 30-300M images is not sufficient to saturate the largest models (p. 2)

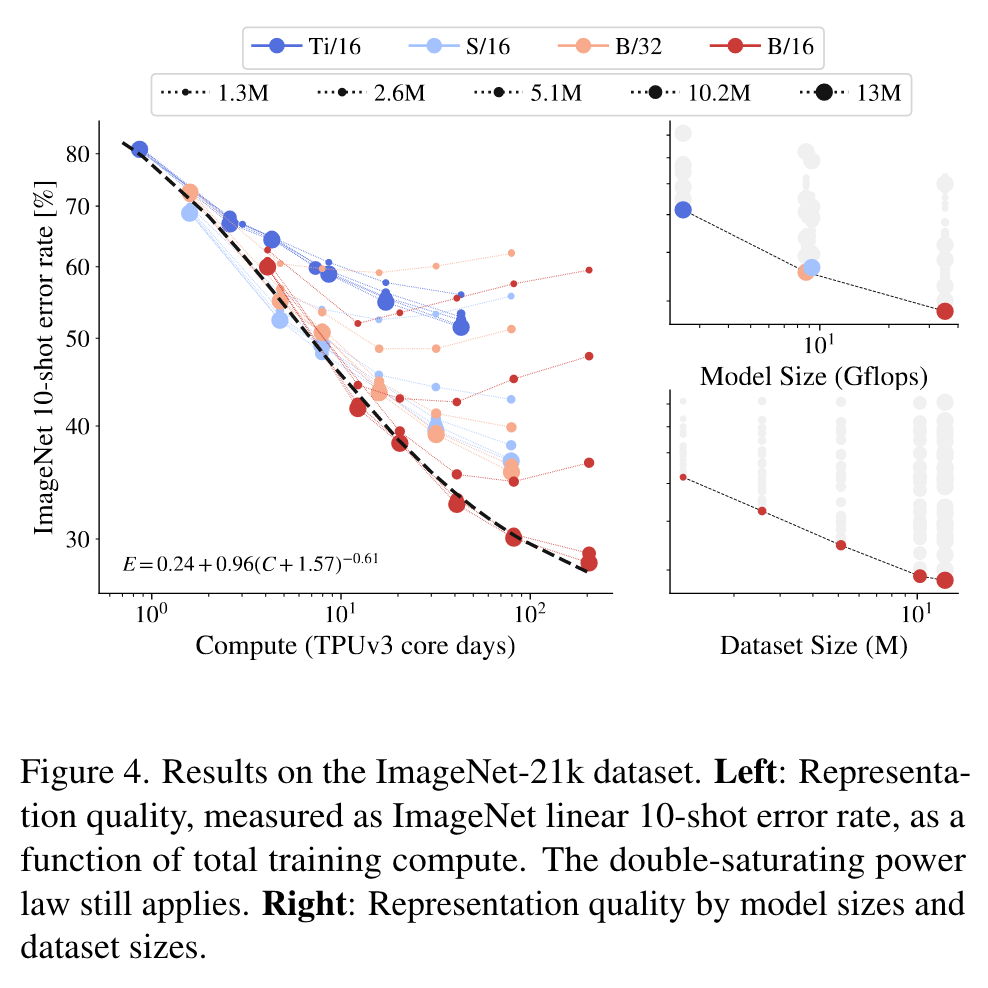

Double-saturating power law

At the higher end of compute, the largest models do not tend towards zero error-rate. If we extrapolate from our observations, an infinite capacity model will obtain a non-zero error. (p. 3)

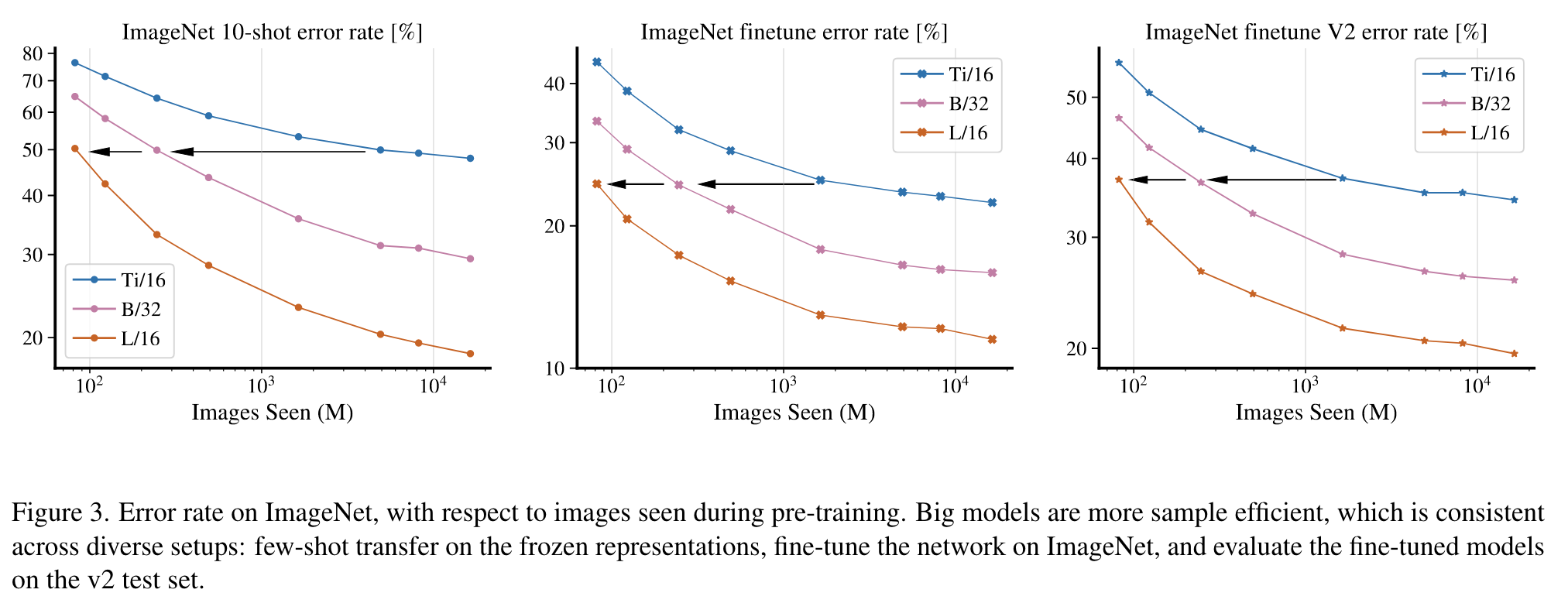

Big models are more sample efficient

We observe that bigger models are more sample efficient, reaching the same level of error rate with fewer seen images (p. 3)

Do scaling laws still apply on fewer images?

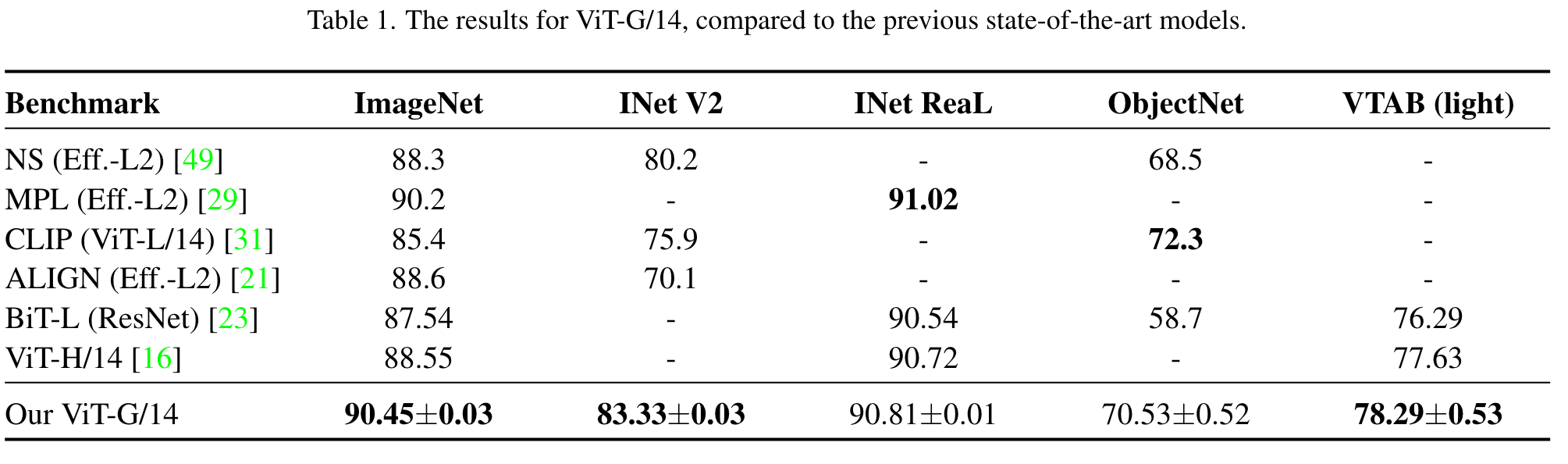

ViT-G/14 results

Method details

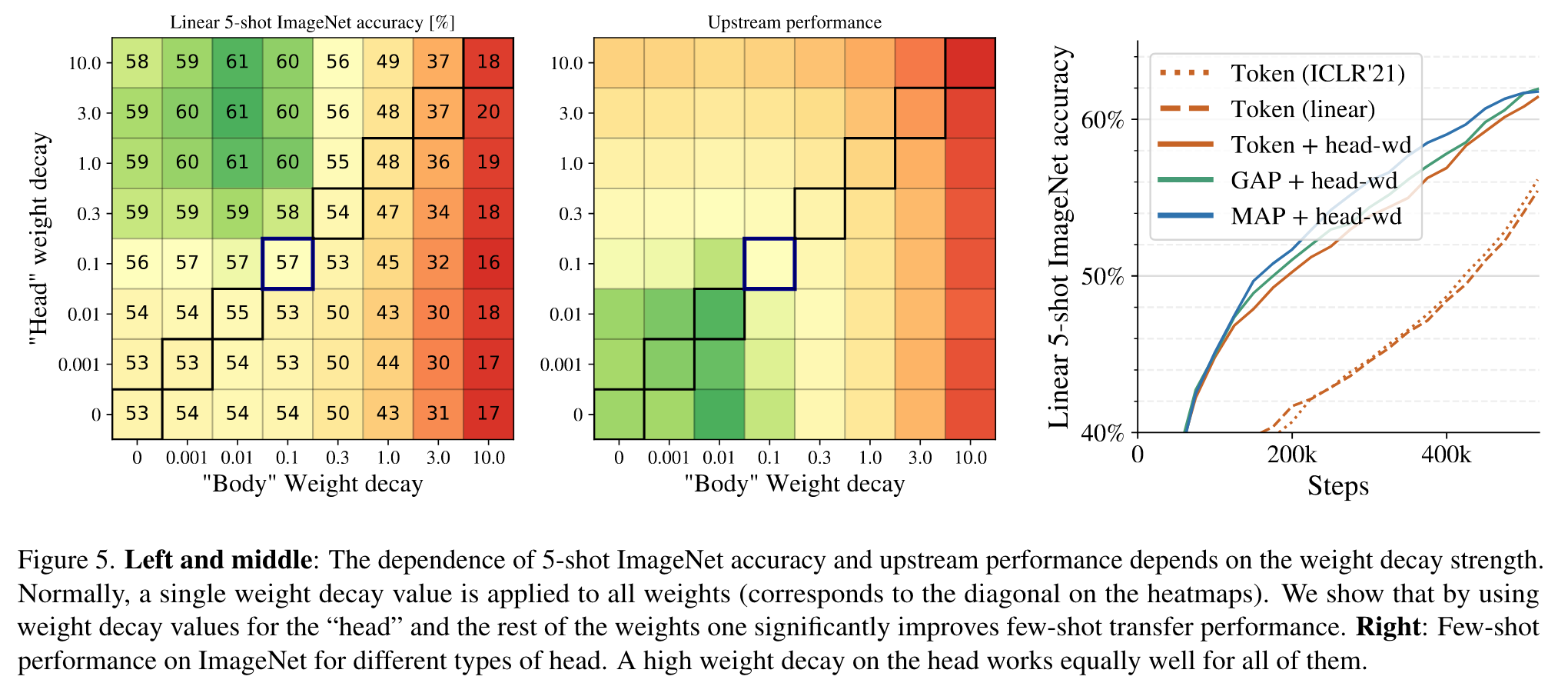

Decoupled weight decay for the “head”

Weight decay has a drastic effect on model adaptation in the low-data regime. (p. 4)

We find that one can benefit from decoupling weight decay strength for the final linear layer (“head”), and for the remaining weights (“body”) in the model. Interestingly, we observe that high weight decay in the head decreases performance on the pre-training (upstream) task (not shown), despite improving transfer performance (p. 4)

However, we hypothesize that a stronger weight decay in the head results in representations with larger margin between classes, and thus better few-shot adaptation. This is similar to the main idea behind SVMs [12]. This large decay makes it harder to get high accuracy during upstream pre-training, but our main goal is high quality transfer. (p. 5)

Saving memory by removing [class] token

We find that all heads perform similarly, while GAP and MAP are much more memory efficient due to the aforementioned padding considerations. We also observe that non-linear projection can be safely removed. Thus, we opt for the MAP head, since it is the most expressive and results in the most uniform architecture. MAP head has also been explored in [42], in a different context for better quality rather than saving memory. (p. 5)

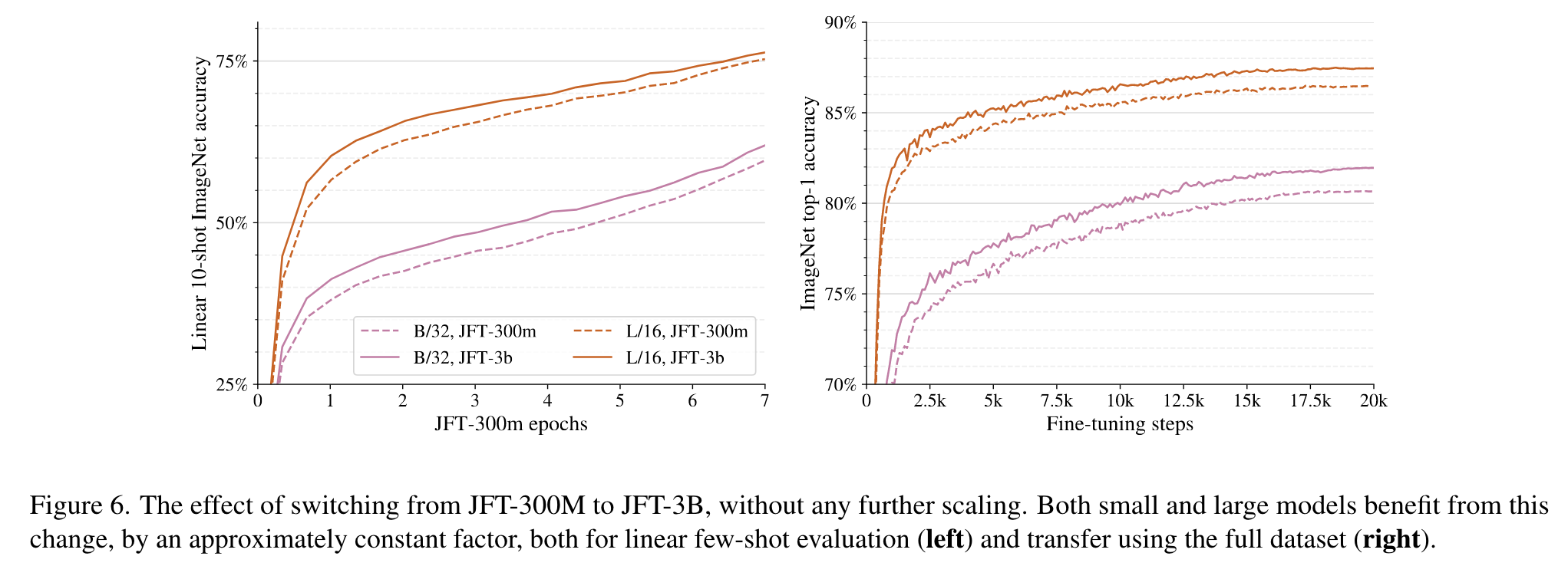

Scaling up data

Memory-efficient optimizers

When training large models, storage required for model parameters becomes a bottleneck. Our largest model, ViT-G, has roughly two billion parameters, which occupies 8 GiB of device memory. To make things much worse, the Adam optimizer that is commonly used for training Transformers, stores two additional floating point scalars per each parameter, which results in an additional two-fold overhead (extra 16 GiB). To tackle the overhead introduced by the Adam optimizer we explore two modifications. (p. 6)

Adafactor optimizer. The above optimizer still induces a large memory overhead. Thus, we turn our attention to the Adafactor optimizer [35], which stores second momentum using rank 1 factorization. From practical point of view, this results in the negligible memory overhead. However, the Adafactor optimizer did not work out of the box, so we make the following modifications: (p. 6)

- We re-introduce the first momentum in half-precision, whereas the recommended setting does not use the first momentum at all.

- We disable scaling of learning rate relative to weight norms, a feature that is part of Adafactor.

- Adafactor gradually increases the second momentum from 0.0 to 1.0 throughout the course of training. In our preliminary experiments, we found that clipping the second momentum at 0.999 (Adam’s default value) results in better convergence, so we adopt it (p. 6)

The resulting optimizer introduces only a 50% memory overhead on top the space needed to store model’s parameters. (p. 6)

We observe that both proposed optimizers perform on par with or slightly better than the original Adam optimizer (p. 6)

Learning-rate schedule

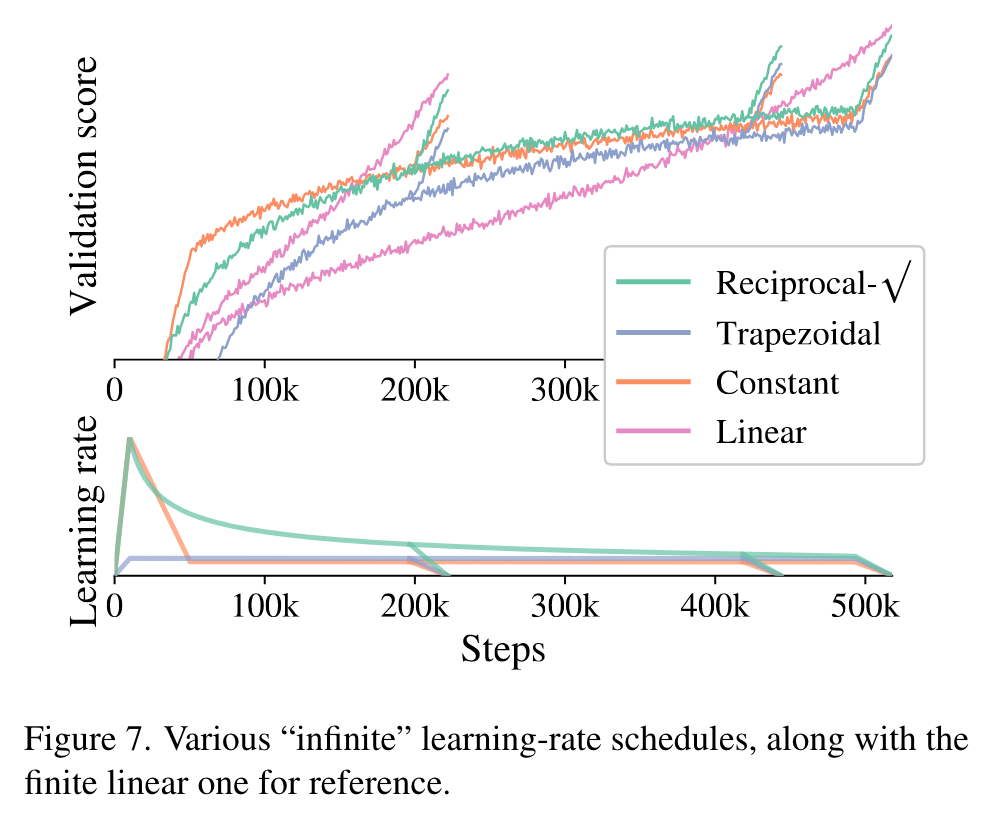

Inspired by [27], we address this issue by exploring learning-rate schedules that, similar to the warmup phase in the beginning, include a cooldown phase at the end of training, where the learning-rate is linearly annealed toward zero. Between the warmup and the cooldown phases, the learning-rate should not decay too quickly to zero. This can be achieved by using either a constant, or a reciprocal squareroot schedule for the main part of training. (p. 6)

Figure 7 shows the validation score (higher is better) for each of these options and their cooldowns, together with two linear schedules for reference. While the linear schedule is still preferable when one knows the training duration in advance and does not intend to train any longer, all three alternatives come reasonably close, with the advantage of allowing indefinite training and evaluating multiple training durations from just one run (p. 6)

Selecting model dimensions

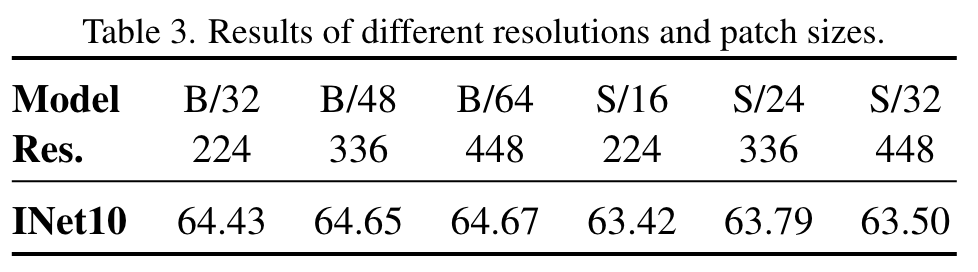

Impact of resolution and patch size

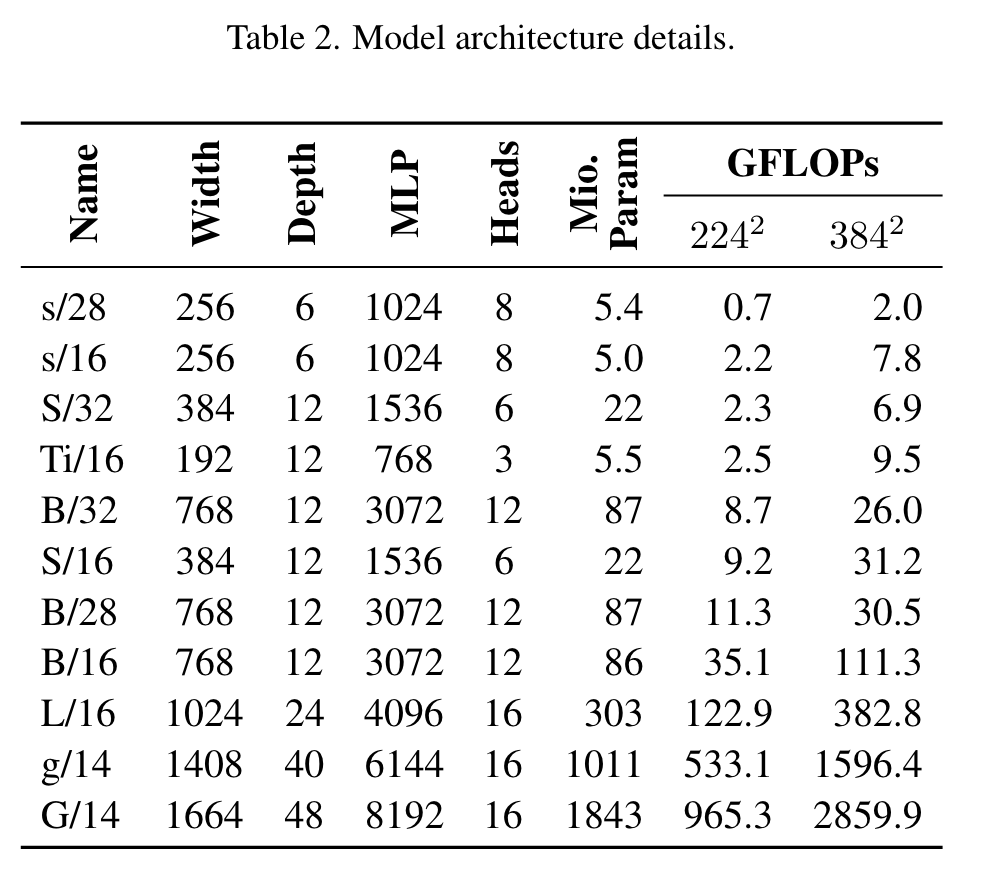

We observed in Table 3 that the quality difference is pretty subtle if we increase patch and resolution together. What matters for ViT architecture is the total number of patches, which has already been covered in Table 2 with different patch sizes: 32, 28, 16, and 14. (p. 12)