Pix2seq A Language Modeling Framework for Object Detection

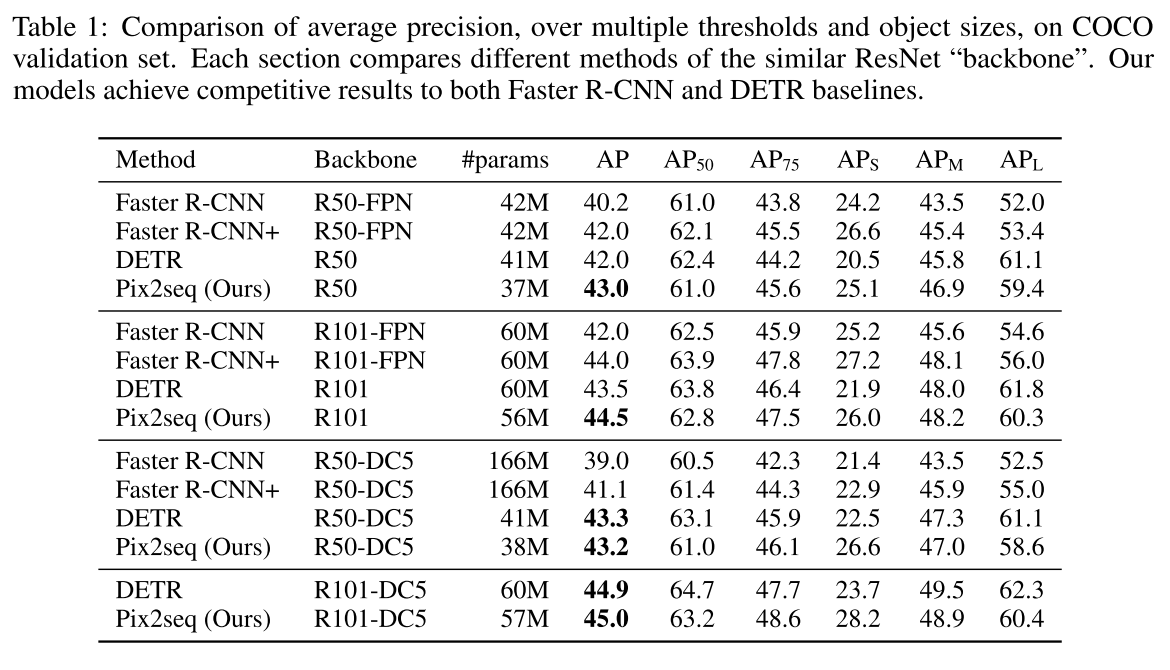

[multimodality image-caption object-detection deep-learning resnet transformer coco Pix2seq: A Language Modeling Framework for Object Detection casts object detection as a language modeling task conditioned on the observed pixel inputs. Object descriptions (e.g., bounding boxes and class labels) are expressed as sequences of discrete tokens, and we train a neural network to perceive the image and generate the desired sequence. Our approach is based mainly on the intuition that if a neural network knows about where and what the objects are, we just need to teach it how to read them out. Experiment results are shown in Table 1, which indicates Pix2seq achieves state of art result on coco.

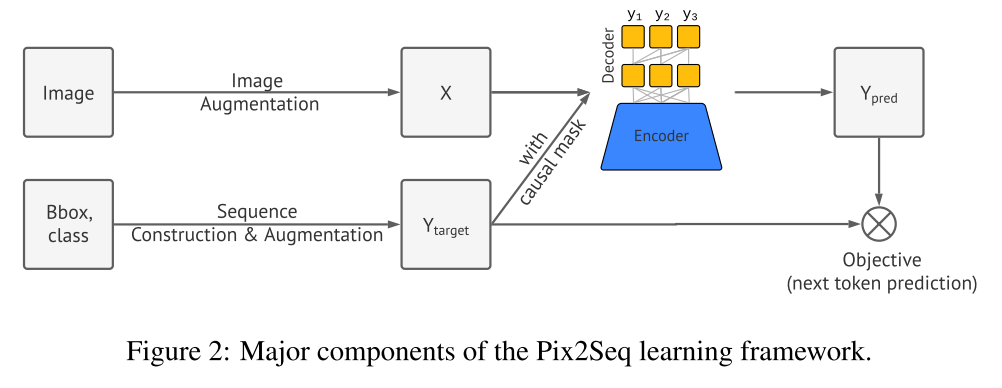

Architecture

Figure 2 shows the architecture of the Pix2Seq. The image will go through an encoder (could be CNN or transformer) and decoder (transformer) takes the image feature and generate the tokens to match the bounding box and object labels.

| At inference time, we sample tokens from model likelihood, i.e., $$P(y_j | x, y_{1:j−1})$$. This can be done by either taking the token with the largest likelihood (arg max sampling), or using other stochastic sampling techniques. We find that using nucleus sampling (Holtzman et al., 2019) leads to higher recall than arg max sampling (Appendix C). The sequence ends when the EOS token is generated. Once the sequence is generated, it is straight-forward to extract and de-quantize the object descriptions (i.e., obtaining the predicted bounding boxes and class labels). |

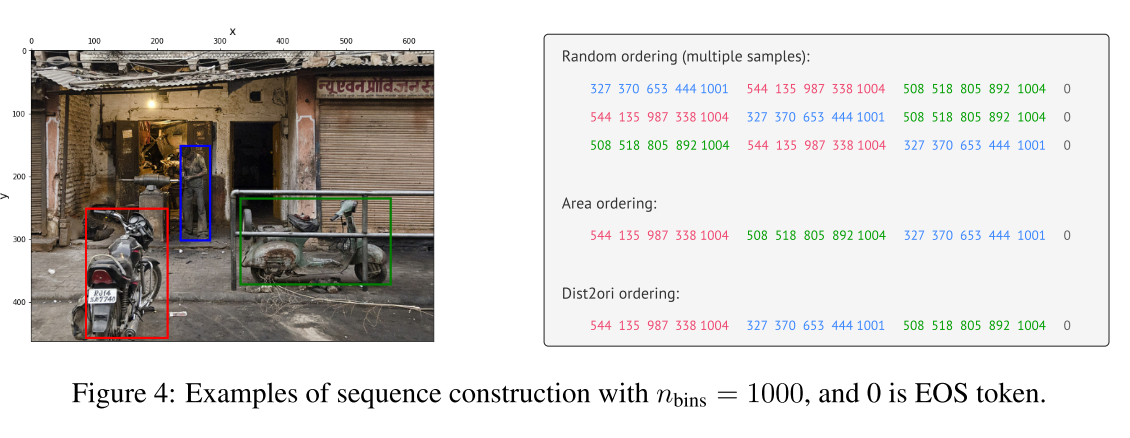

SEQUENCE CONSTRUCTION FROM OBJECT DESCRIPTIONS

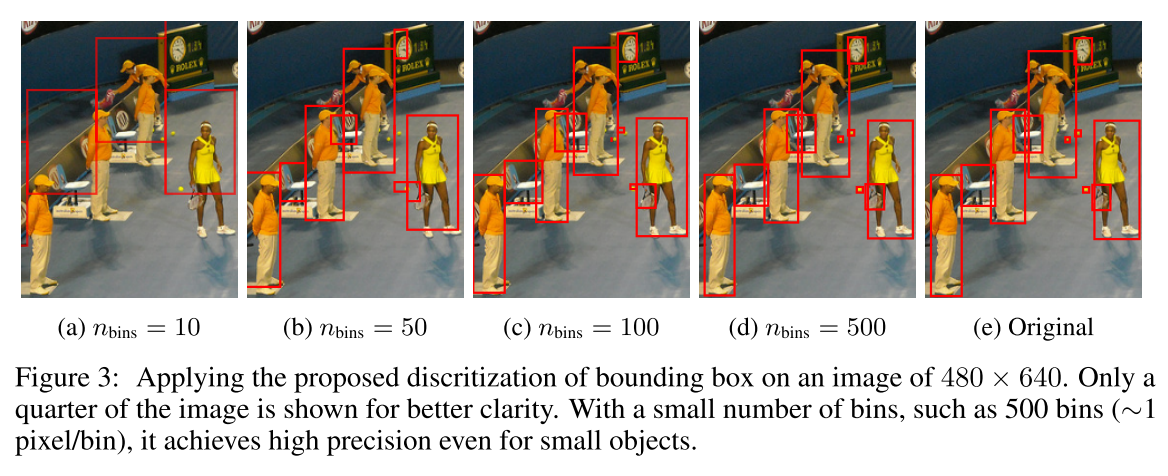

We propose to discretize the continuous numbers used to specify the x, y coordinates of corner points (similarly for height and width if the other box format is used). Specifically, an object is represented as a sequence of five discrete tokens, i.e. [ymin, xmin, ymax, xmax, c], where each of the continuous corner coordinates is uniformly discretized into an integer between [1, nbins], and c is the class index. We use a shared vocabulary for all tokens, so the vocabulary size is equal to number of bins + number of classes. Check Figure 3 for an example.

With each object description expressed as a short discrete sequence, we next need to serialize multiple object descriptions to form a single sequence for a given image. Since order of objects does not matter for the detection task per se, we use a random ordering strategy (randomizing the order objects each time an image is shown). Finally, because different images often have different numbers of objects, the generated sequences will have different lengths. To indicate the end of a sequence, we therefore incorporate an EOS token. Figure 4 shows an example.

Data Augmentation

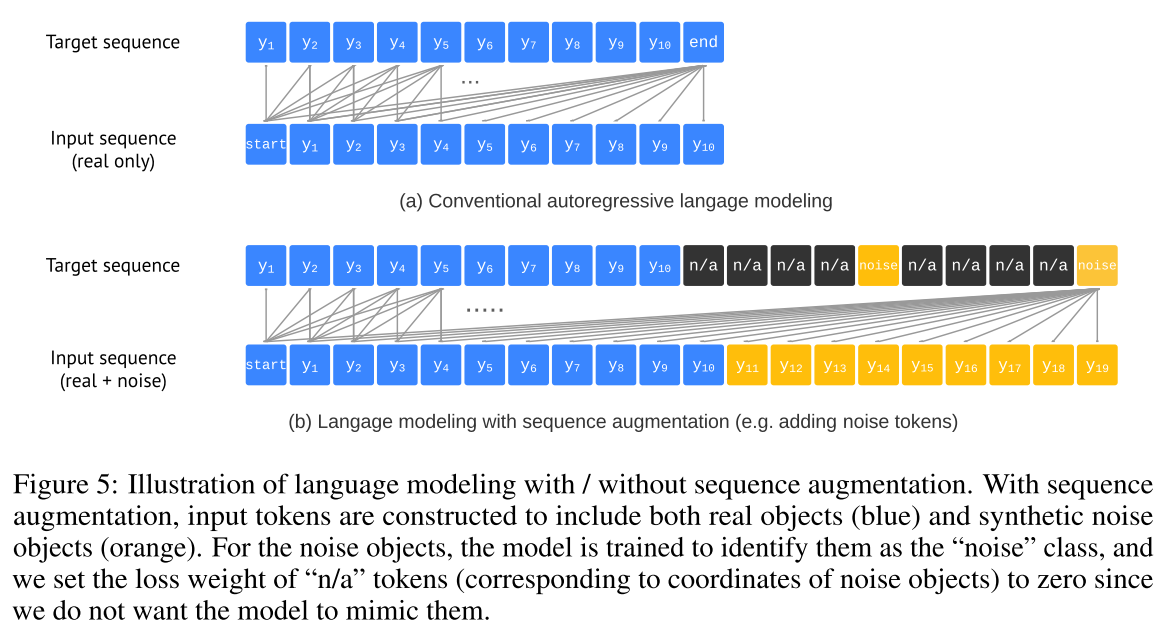

The EOS token allows the model to decide when to terminate generation, but in practice we find that the model tends to finish without predicting all objects. This is likely due to 1) annotation noise (e.g., where annotators did not identify all the objects), and 2) uncertainty in recognizing or localizing some objects. It becomes a trade off between precision and recall.

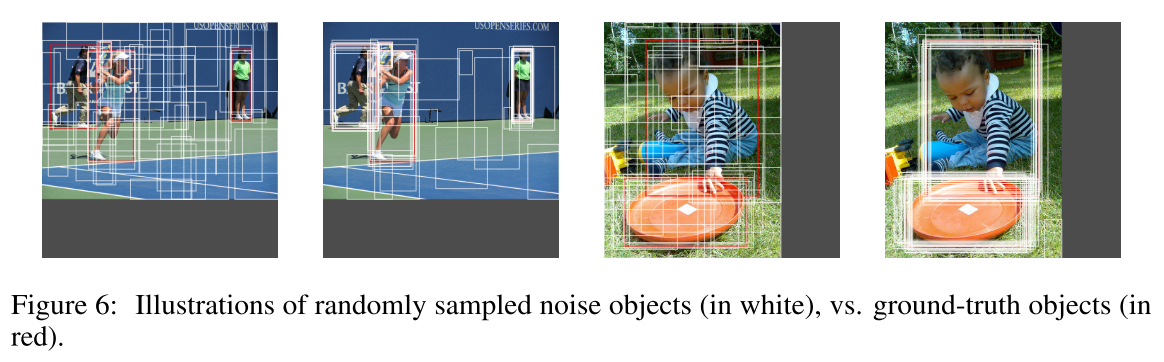

With sequence augmentation, we instead augment input sequences during training to include both real and synthetic noise tokens. We also modify target sequences so that the model can learn to identify the noise tokens rather than mimic them. This improves the robustness of the model against noisy and duplicated predictions (particularly when the EOS token is delayed to increase recall).

Altered sequence construction We first create synthetic noise objects to augment input sequences in the following two ways: 1) adding noise to existing ground-truth objects (e.g., random scaling or shifting their bounding boxes), and 2) generating completely random boxes (with randomly associated class labels).

With sequence augmentation, we are able to substantially delay the EOS token, improving recall without increasing the frequency of noisy and duplicated predictions. Thus, we let the model predict to a maximum length, yielding a fixed-sized list of objects. When we extract the list of bounding boxes and class labels from the generated sequences, we replace the “noise” class label with a real class label that has the highest likelihood among all real class labels. We use the likelihood likelihood of the selected class token as a (ranking) score for the object.