TiC-CLIP Continual Training of CLIP Models

[multimodal deep-learning tic-clip clip continuous-learning finetune This is my reading note for TiC-CLIP: Continual Training of CLIP Models. This paper studies the problem of how a model performs as the dataset evolve over time. It then proposes the best solutions base on benchmark, which is fine tuned the existing model on the whole dataset, include both new and old data.

Introduction

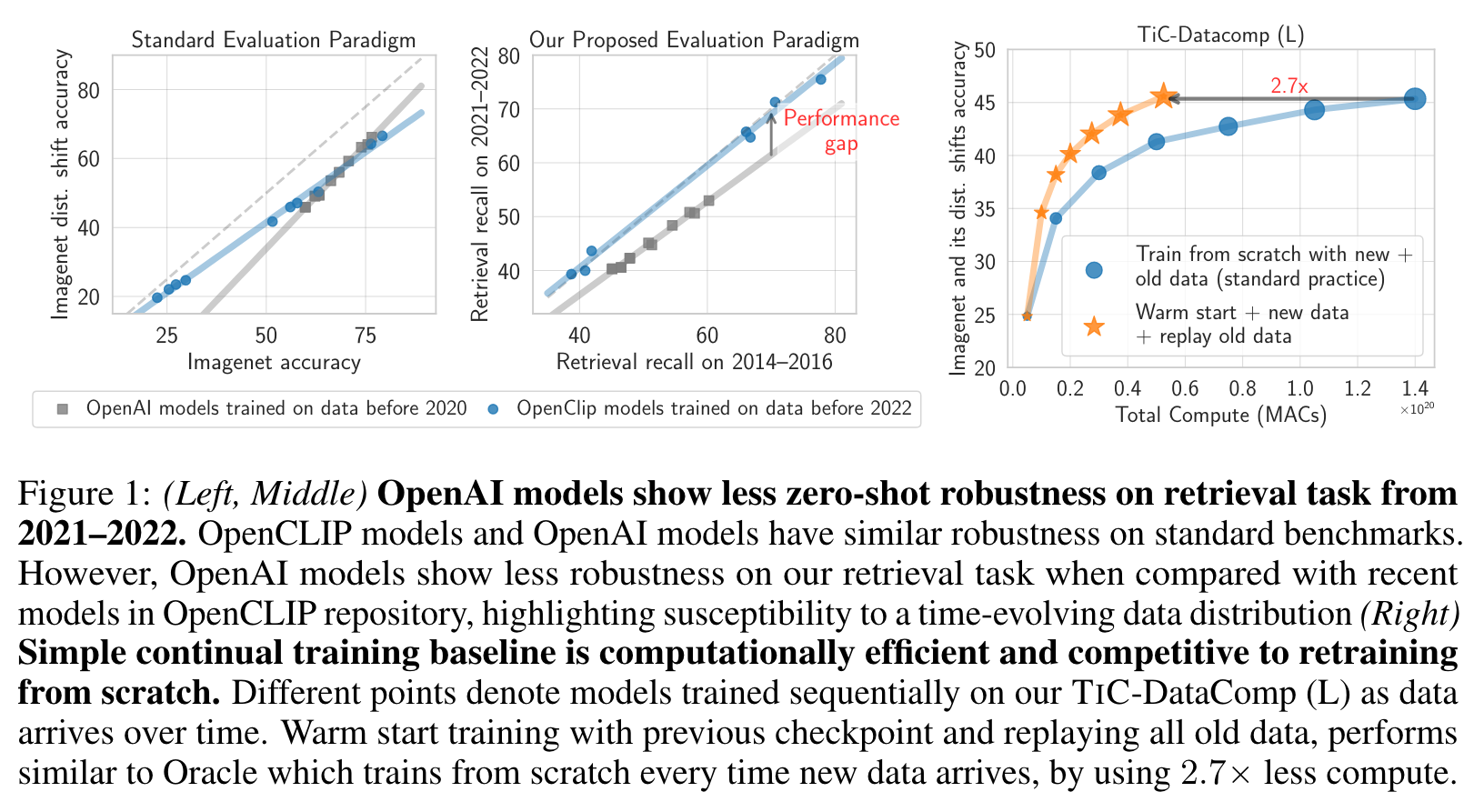

We then study how to efficiently train models on time-continuous data. We demonstrate that a simple rehearsal-based approach that continues training from the last checkpoint and replays old data reduces compute by 2.5ˆ when compared to the standard practice of retraining from scratch. (p. 1)

One naive but common practice for adapting to time-evolving data is to train a new CLIP model from scratch every time we obtain a new pool of image-text data. This practice has its rationale: initiating training from a pre-existing model can make it difficult to change the model’s behavior in light of new data (p. 2)

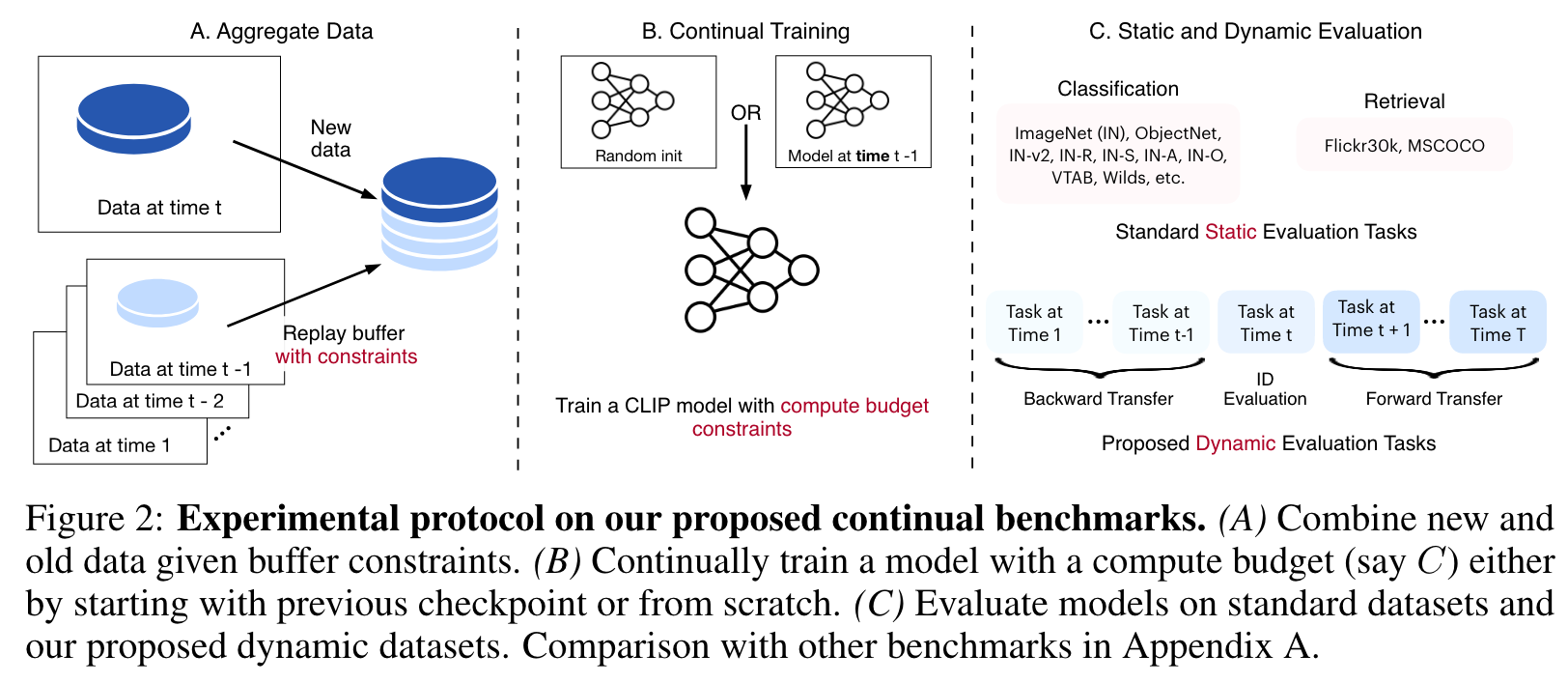

We take the first step towards Time-Continual (TIC) training of CLIP models where data distribution evolves naturally over time (overview in Fig. 2). (p. 2)

Cumulative method that warm starts training with the latest checkpoint and replays all old data, achieves performance competitive to an Oracle while being 2.7ˆ computationally more efficient. (p. 3)

RELATED WORK

Neural networks trained on new data suffer from catastrophic forgetting of prior knowledge Continual learning methods can be categorized broadly into

- regularization: Regularization methods push the model to change slowly in the directions of prior knowledge and often incur additional memory/compute costs (Kirkpatrick et al., 2017; Mirzadeh et al., 2020a;b; Farajtabar et al., 2020).

- replay: Data replay methods retain all or a subset of the prior data for either retraining or regularization (Lopez-Paz & Ranzato, 2017; Rebuffi et al., 2017; Chaudhry et al., 2018). Simple replay-based baselines can surpass various methods on standard benchmarks (Lomonaco et al., 2022; Balaji et al., 2020; Prabhu et al., 2020).

- architecture-based methods: architecture-based methods expand the model as new tasks arrive which limits their applicability in continually evolving environments (Schwarz et al., 2018; Rusu et al., 2016). (p. 9)

TIC-CLIP: BENCHMARKS AND EXPERIMENTAL PROTOCOL

BENCHMARK DESIGN: HOW WE CREATE TIME-CONTINUAL DATASETS?

To instantiate continual training of CLIP, we extend existing image-text datasets with time information collected from the original source of the datasets. (p. 3)

EVALUATION TESTBED

Dynamic tasks

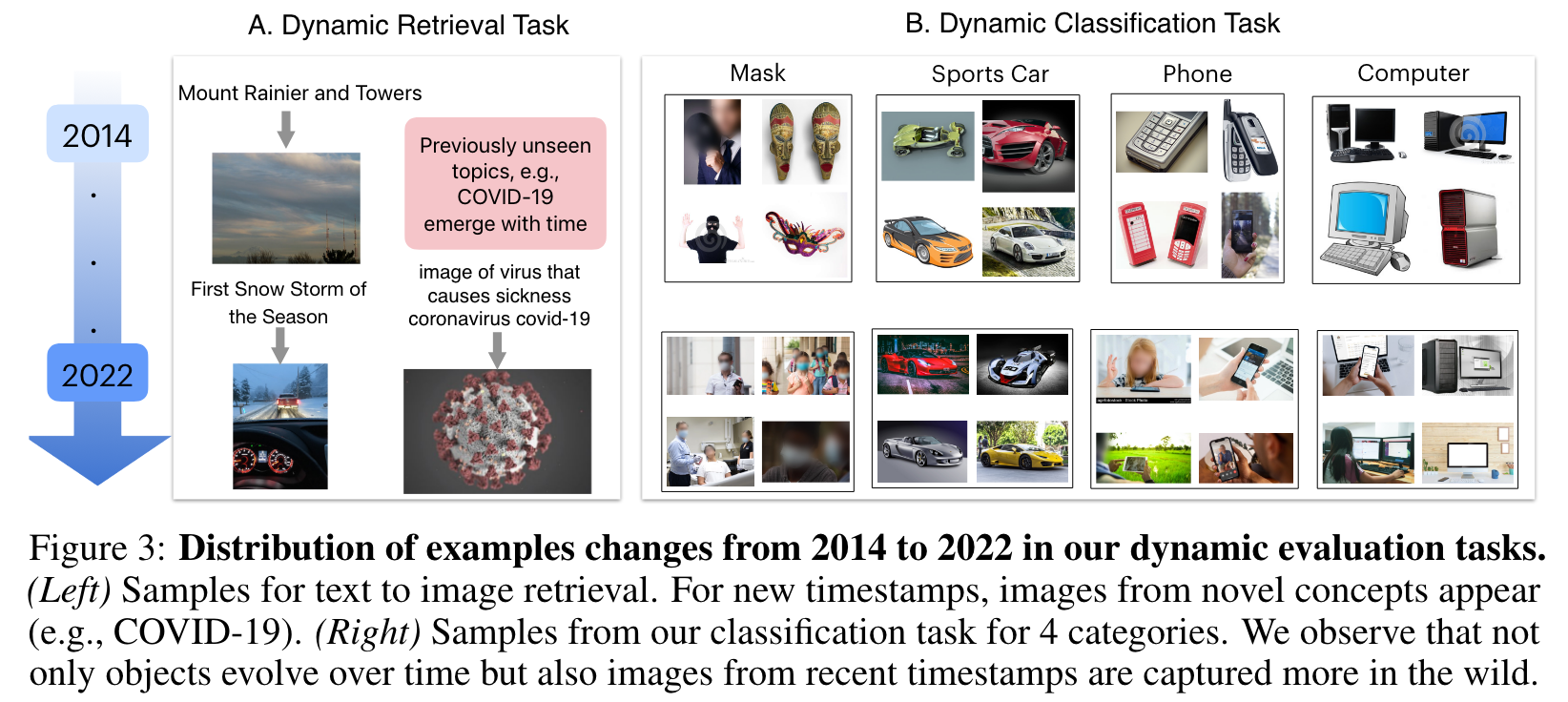

We leverage the temporal information in our benchmarks to create dynamic evaluation tasks. Here, the test data comprises samples varying over years as the world evolved. (p. 4)

- Dynamic retrieval task: To create a retrieval task, we sample a batch of IID image-text pairs from different timestamps and evaluate text retrieval performance given the corresponding image (similarly, image retrieval given the corresponding text) (p. 4)

- Dynamic classification task: We also create a classification dataset TIC-DataComp-Net with Ima- geNet classes from CommonPool and augmented with timestamps. (p. 4)

Static tasks

We also evaluate models on numerous classification and retrieval tasks in a zero- shot manner as in Radford et al. (2021). In particular, we consider 28 standard tasks: 27 image classification tasks, e.g., ImageNet and its 6 distribution shifts (e.g., ImageNetv2, ImageNet-R, ImageNet-Sketch, and Objectnet), datasets from VTAB and Flickr30k retrieval task. We refer to these as static evaluation tasks. (p. 5)

Evaluation metrics

We define metrics for classification tasks and retrieval tasks based on accuracy and Recall@1, respectively. (p. 5)

- In-domain performance: average performance at each training time step (i.e., the diagonal of E)

- Backward transfer: average on time steps before each training step (i.e., the lower triangular of E)

- Forward transfer: average on time steps following each training step (i.e., the upper triangular of E) (p. 5)

ANALYZING DISTRIBUTION SHIFTS IN THE CONSTRUCTED BENCHMARKS

We observe that over time, in the retrieval task, new concepts like COVID-19 emerge. Likewise, certain ImageNet classes evolve, such as the shift from “masquerad” masks to “surgical/protective” masks in their definitions. Moreover, as time evolves, we observe that image quality improves and more images tend to appear in the wild in contrast to centered white background images (p. 5)

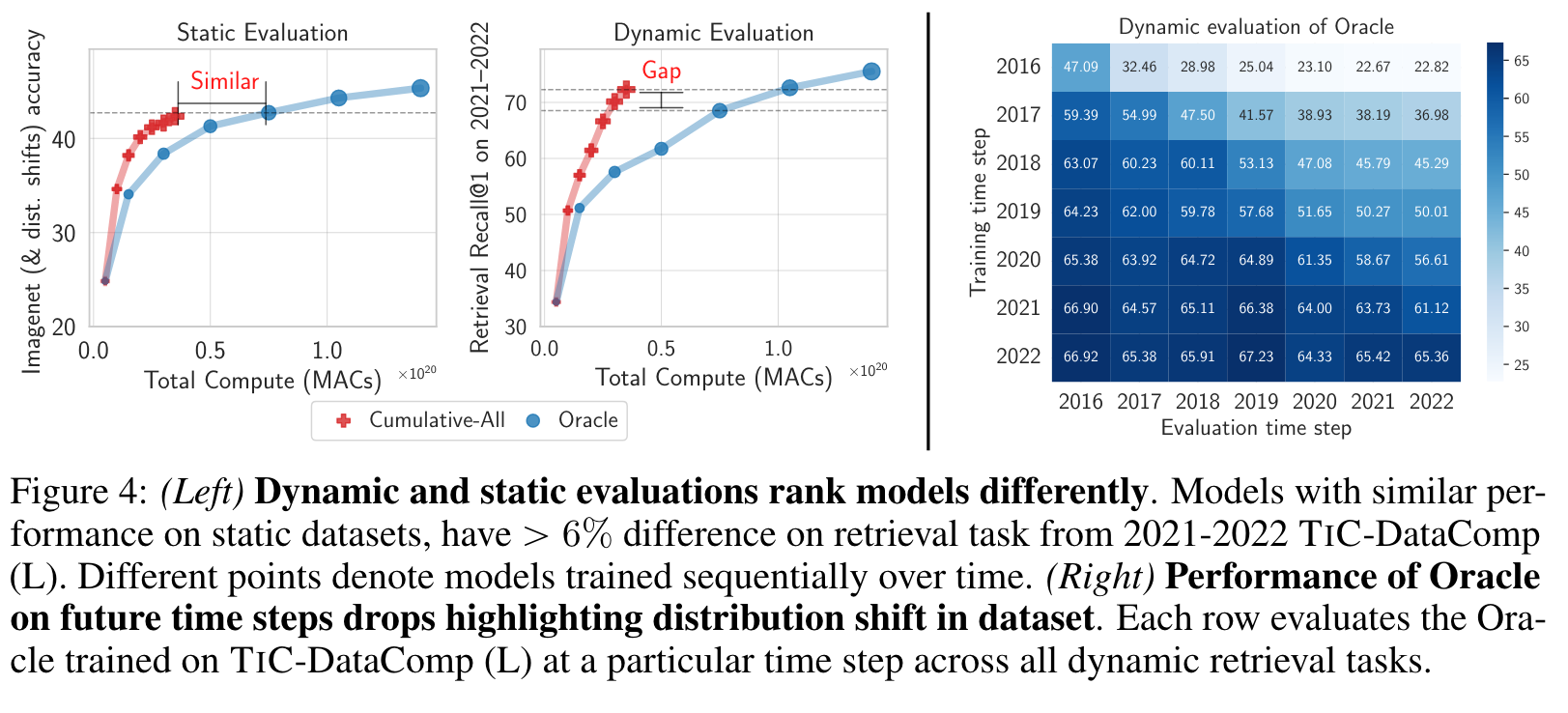

We observe a significant performance gap between OpenAI and OpenCLIP models on our dynamic retrieval task (Fig. 1). This gap widens notably on retrieval queries where captions mention COVID-19. On the other hand, OpenAI and OpenCLIP models exhibit similar robustness for retrieval on data coming from Flickr highlighting that data from some domains do not exhibit shifts that cause performance drops. For our classification task, we observe a very small drop (« 1%) when averaged across all categories. However, we observe a substantial gap on specific subtrees in ImageNet. For example, classes in “motor vehicle” subtree show an approximate 4% performance drop, when comparing OpenAI and OpenCLIP models. These findings highlight that while overall ImageNet classes may remain timeless, certain categories tend to evolve faster than others. (p. 6)

TIC-CLIP: HOW TO CONTINUALLY TRAIN CLIP MODELS?

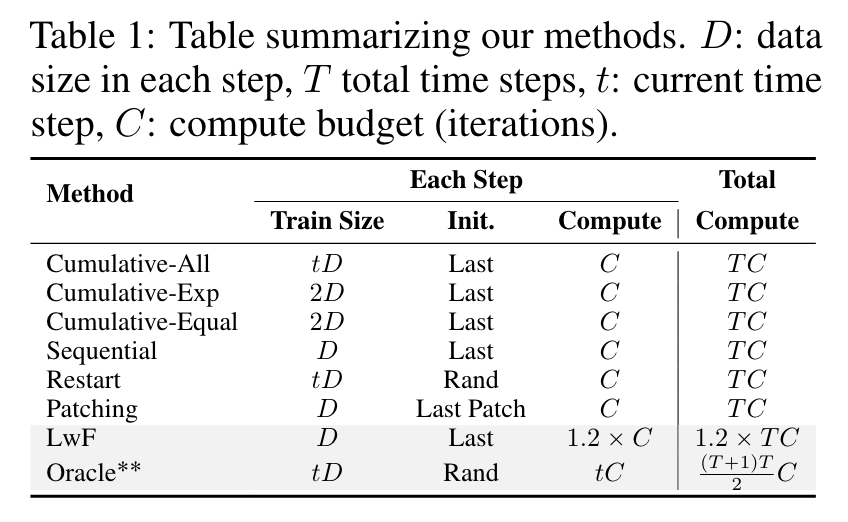

- Oracle: Train a CLIP model from scratch (i.e., random initialization) on all image-text data received till time t using a large compute budget of t ˆ C. (p. 6)

- Cumulative: Train each model initialized from last checkpoint on the union of all data up to t with compute budget C. This method is analogous to Experience Replay Given a fixed buffer size for each past step, we observe minimal to no difference between random subsampling and other strategies. After sampling the replay data, we randomly shuffle it together with new data for training. (p. 6)

- Sequential: Train only on the new data starting from the best checkpoint of the previous time step. (p. 6)

- Restart: Train each model from scratch (i.e., random initialization) on all the data till time t for compute budget C. (p. 6)

- LwF: Train only on the new data with an additional loss that regularizes the model by KL divergence between the image-text similarity matrix of last checkpoint and current model on each mini-batch (Li & Hoiem, 2017; Ding et al., 2022). (p. 7)

- Patching: We use sequential patching from Ilharco et al. (2022) and initialize from a patched model of last step and train only on the new data. To obtain patched model at each time step, we apply weight interpolation with the patched model (if any) trained at time step t´1 and model trained at time step t. We tune the mixing coefficients by optimizing average retrieval performance on previous tasks. (p. 7)

EXPERIMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS

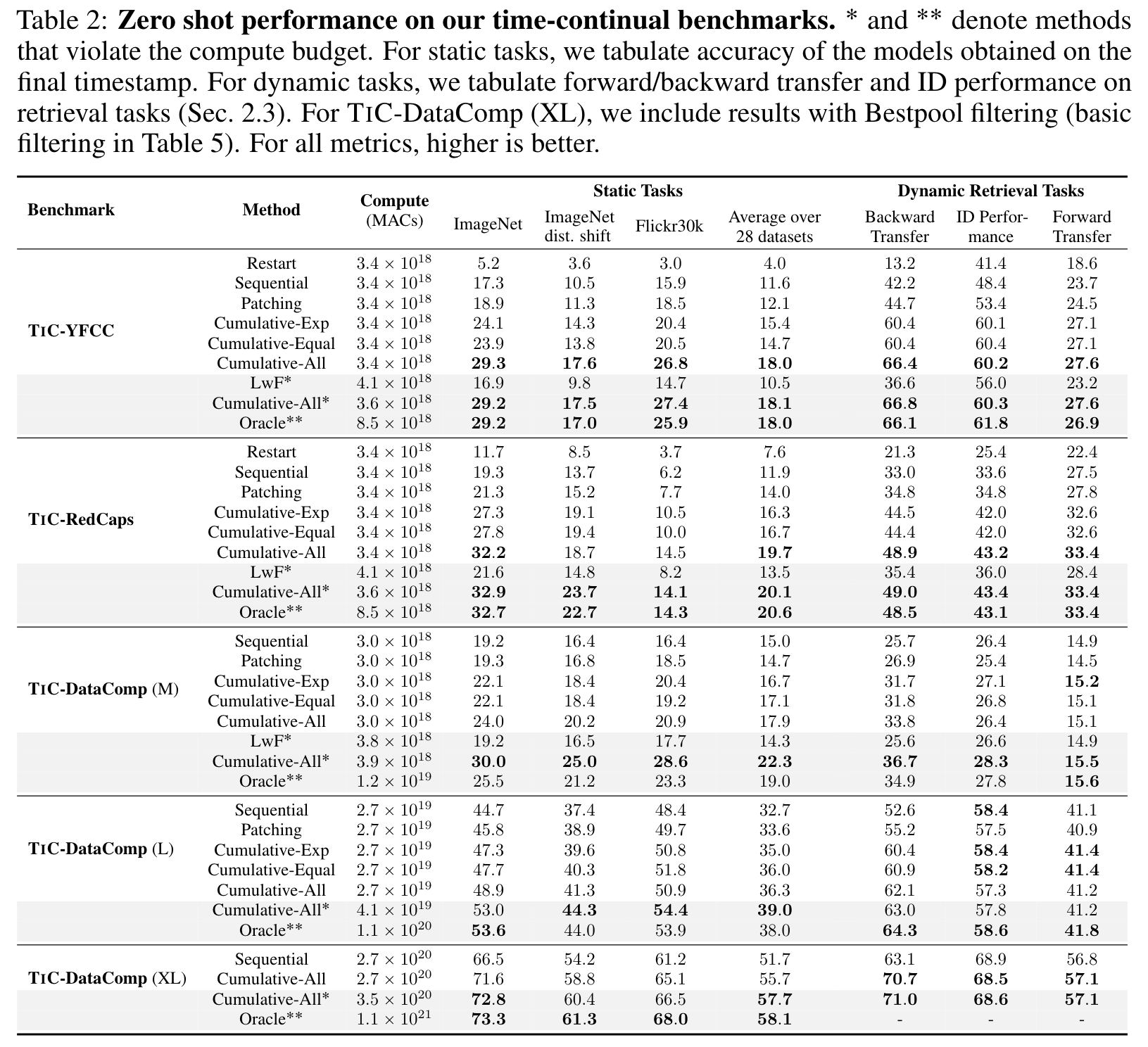

Cumulative-All saves up to 4ˆ the cost. On dynamic evaluation tasks, we observe that Cumulative- All where we replay all the past data, achieves performance close to the Oracle (within 1%) using significantly less compute. This highlights that with unconstrained access to past data, we can simply train sequentially and save significant computational resources. (p. 8)

These results hint that to continuously improve on static tasks with time, replaying old data as in Cumulative-All plays a crucial role. (p. 8)

While reducing the buffer sizes, these methods still achieve performance close to Cumulative-All (within 2%) on both static and dynamic tasks, with -Equal consistently better than -Exp strategy. As we go to large scale, e.g., from medium to large, the gap between these methods and Cumulative-All reduces. These findings demonstrate that even a small amount of replay data from old time steps stays competitive with replaying all data and significantly improves over no replay at all. (p. 8)

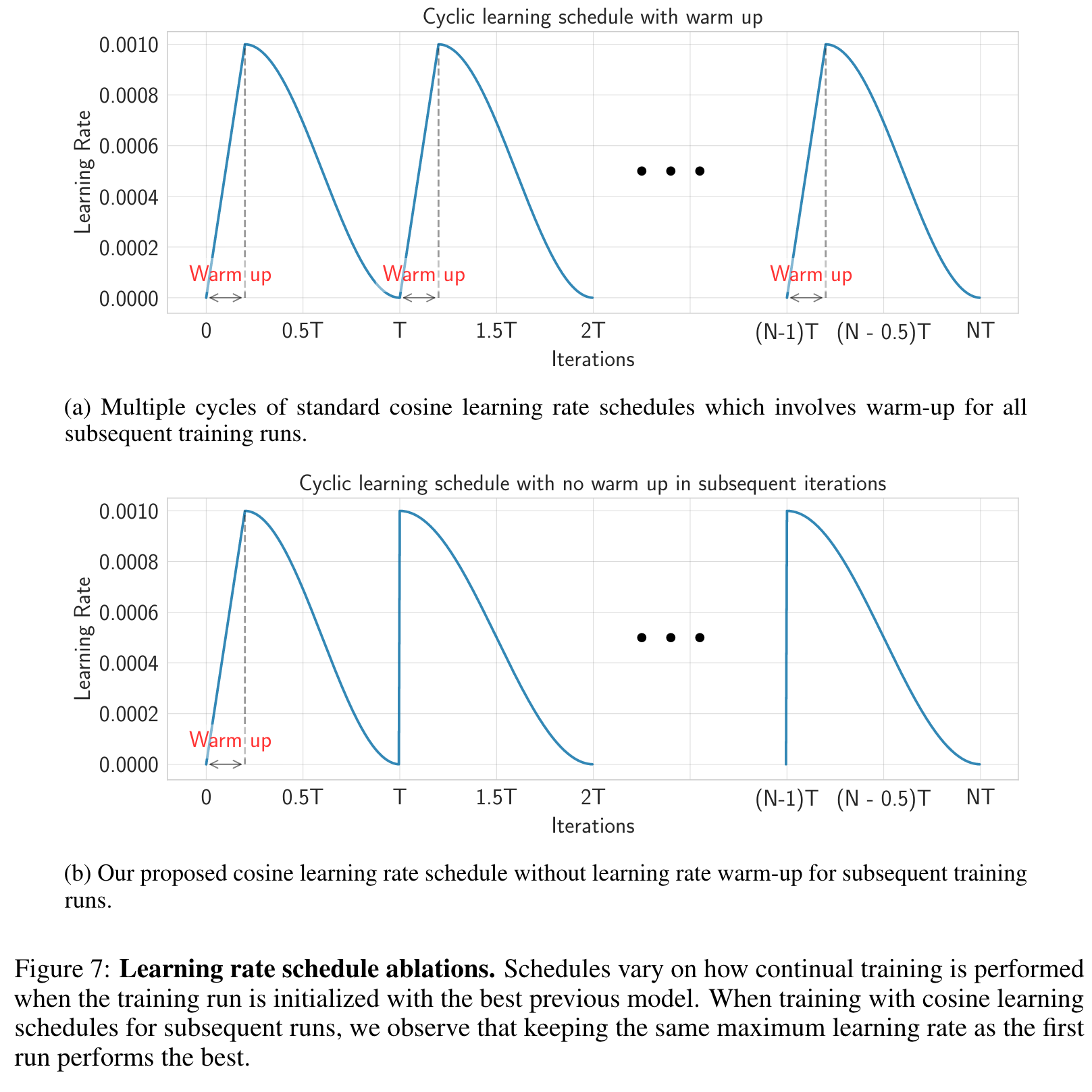

We investigate the effectiveness of warm-up in first versus subsequent time steps. Surprisingly, we observe that not using warmup for subsequent training runs is strictly more beneficial than using warm up on both static and dynamic tasks. (p. 8)

we observe that decaying maximum LR for subsequent steps in our setup hurts on static and dynamic tasks and consequently, we use same maximum LR across our runs (p. 9)

Choosing models solely based on static task performance may inadvertently select models that underperform on dynamic tasks. (p. 9)

Learning Rate Ablation