Towards Practical Capture of High-Fidelity Relightable Avatars

[face relightable nerf deep-learning mixture-volumetric-presentation 3d This is my reading note for Towards Practical Capture of High-Fidelity Relightable Avatars. This paper proposes a method to relight mixture volume representation for the face. The major contribution is to explicitly to enforce linearity of light to the network.

Introduction

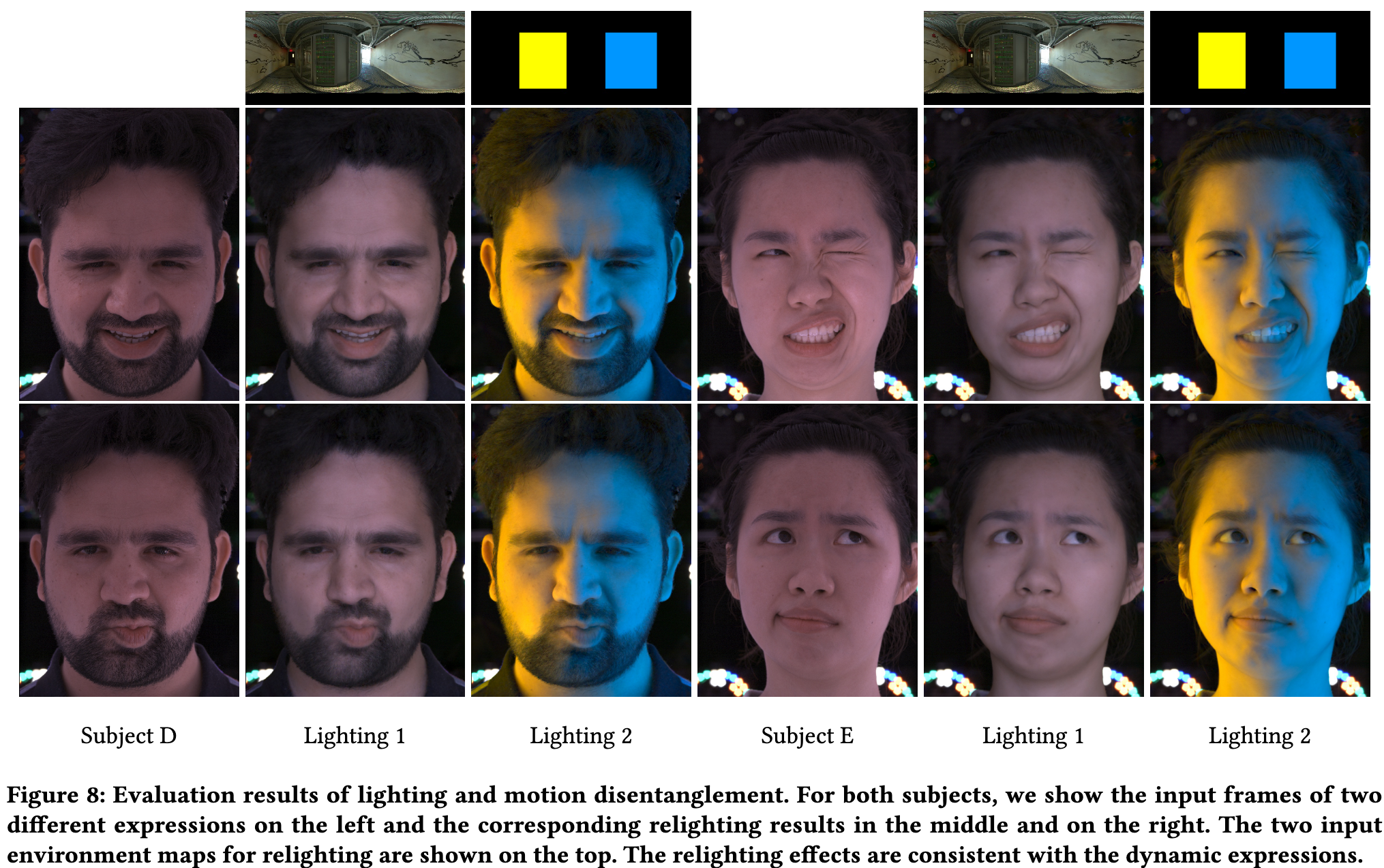

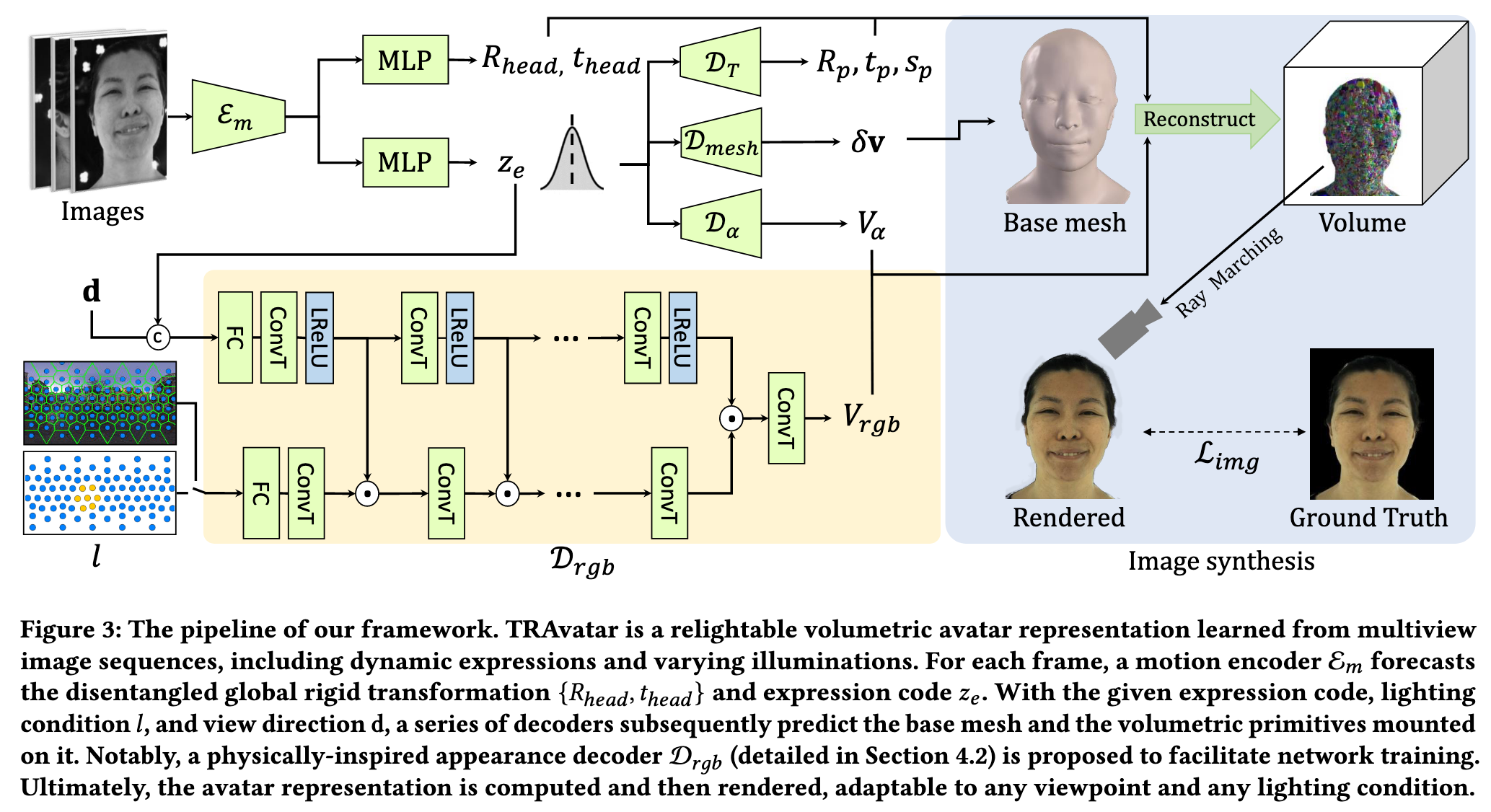

Specifically, TRAvatar is trained with dynamic image sequences captured in a Light Stage under varying lighting conditions, enabling realistic relighting and real-time animation for avatars in diverse scenes. Additionally, TRAvatar allows for tracking-free avatar capture and obviates the need for accurate surface tracking under varying illumination conditions. Our contributions are two-fold: First, we propose a novel network architecture that explicitly builds on and ensures the satisfaction of the linear nature of lighting. Trained on simple group light captures, TRAvatar can predict the appearance in real-time with a single forward pass, achieving high-quality relighting effects under illuminations of arbitrary environment maps. Second, we jointly optimize the facial geometry and relightable appearance from scratch based on image sequences, where the tracking is implicitly learned. This tracking-free approach brings robustness for establishing temporal correspondences between frames under different lighting conditions. (p. 1)

Considering the complexity of lighting conditions, it is non-trivial for the avatar network to directly learn the mapping from environment maps to the appearance. Furthermore, it is challenging to achieve satisfactory decoupling of lighting and other input conditions. To overcome this challenge, we take advantage of the prior knowledge of lighting, specifically its linear nature, to guide the network design. (p. 2)

Related Work

Geometry and reflectance acquisition

Traditional frameworks based on graphics pipeline, including geometry reconstruction [Beeler et al. 2010, 2011; Collet et al. 2015; Guo et al. 2019; Riviere et al. 2020; Wu et al. 2018] and physically-inspired reflectance capture [Debevec et al. 2000; Ghosh et al. 2011; Ma et al. 2007; Moser et al. 2021; Weyrich et al. 2006], are often difficult to set up and lack robustness, especially for dynamic subjects and non-facial parts. Recent deep learning based methods [Bi et al. 2021; Cao et al. 2022; Lombardi et al. 2018, 2021; Remelli et al. 2022] have demonstrated promising improvements for avatar representation by approximating the geometry and appearance with neural networks. However, most learning-based methods struggle to handle relighting effectively and have computationally expensive pre-processing and training steps that cannot meet the aforementioned requirements. (p. 2)

Previous methods usually assume physically-inspired reflectance functions modeled as bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF) [Schlick 1994] and solve the parameters by observing the appearance under active or passive lighting. Active lighting methods typically require specialized setups with controllable illuminations and synchronized cameras. Debevec et al. [2000] pioneer in using a Light Stage for facial reflectance acquisition. One-light-at-a-time (OLAT) capture is performed to obtain the dense reflectance field. Later, polarized [Ghosh et al. 2011; Ma et al. 2007; Zhang et al. 2022] and color gradient illuminations [Fyffe and Debevec 2015; Guo et al. 2019] are used for rapid acquisition. Passive capture methods have significantly reduced the necessity for an expensive capture setup. For example, Riviere et al. [2020] and Zheng et al. [2023] propose to estimate physically-based facial textures via inverse rendering. (p. 3)

3D face modeling

The seminal work on 3D morphable models (3DMMs) [Blanz and Vetter 1999; Cao et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2020] employs Principal Component Analyze (PCA) to derive the shape basis from head scans. Despite its widespread use in various applications such as single-view face reconstruction and tracking [Dou et al. 2017b; Thies et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2017], the shape space of 3DMMs is limited by its low-dimensional linear representation. Follow-up methods separate the parametric space dimensions [Jiang et al. 2019; Li et al. 2017; Vlasic et al. 2005] or use local deformation models [Wu et al. 2016] to enhance the representation power of the morphable model. (p. 3)

In recent years, deep learning based methods [Bagautdinov et al. 2018; Tran and Liu 2018, 2019; Zhang et al. 2022; Zheng et al. 2022] have been widely used to achieve impressive realism in face modeling. Lombardi et al. [2018] utilize a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [Kingma and Welling 2013] to jointly model the mesh and dynamic texture, which is used for monocular [Yoon et al. 2019] and binocular [Cao et al. 2021] facial performance capture. Bi et al. [2021] propose to extend the VAE-based deep appearance model by capturing the dynamic performance under controllable group light illuminations to enable relighting (p. 3)

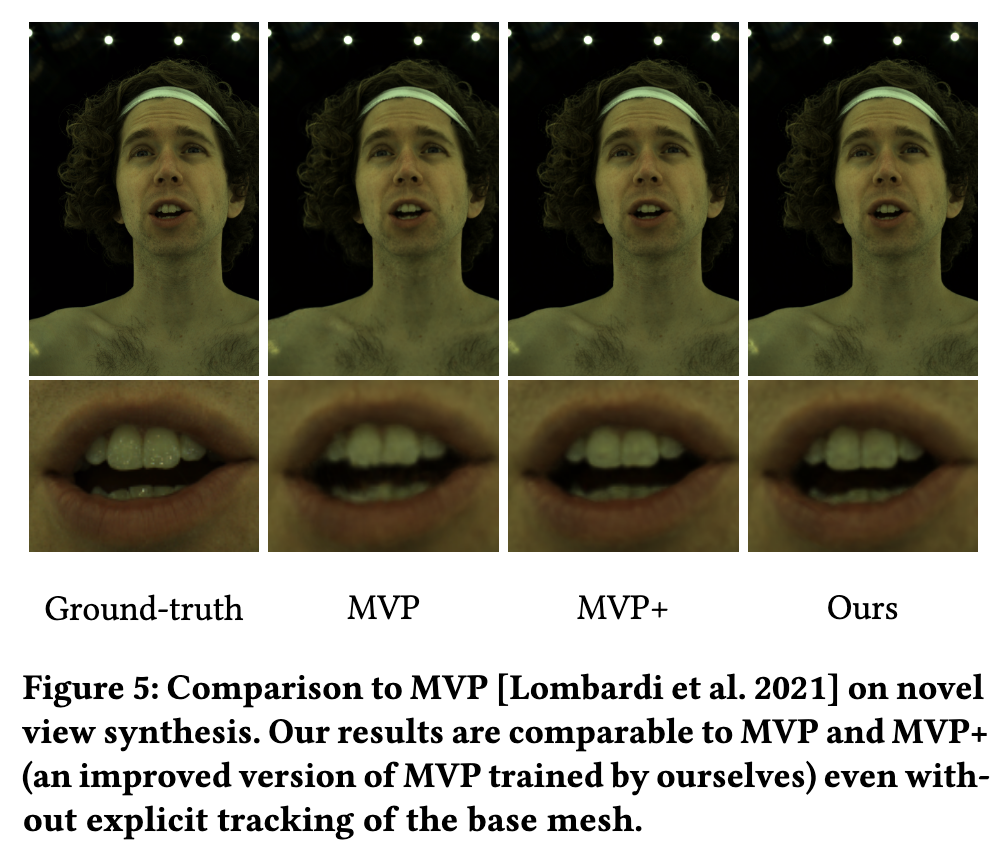

While mesh-based methods typically require dense correspondence based on sophisticated surface tracking algorithms [Beeler et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2018] for training and degrade in non-facial regions, recent progress in neural volumetric rendering further enables photorealistic avatar creation. Lombardi et al. [2021] propose MVP (Mixture of Volumetric Primitives), a hybrid volumetric and primitive-based representation that produces high-fidelity rendering results with efficient runtime performance. More recently, Li et al. [2023] extend MVP with eyeglasses to be relightable following [Bi et al. 2021]. But it requires additional efforts for real-time relighting (p. 3)

Image-based relighting

In contrast to model-based reflectance acquisition approaches, image-based relighting addresses the problem from an orthogonal perspective. By exploiting the linear nature of light transport, Debevec et al. [2000] propose to add up hundreds of images of densely sampled reflectance fields from OLAT capture to synthesize rendering results under novel lighting conditions. Subsequently, the number of sampled images is reduced by using specifically designed illumination patterns [Peers et al. 2009; Reddy et al. 2012] or employing sparse sampling [Fuchs et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2009]. Xu et al. [2018] propose to train a network for relighting a scene from only five input images. Meka et al. [2019] show that the full 4D reflectance field of human faces can be regressed from two images under color gradient light illumination. Sun et al. [2020] propose a learning-based method to achieve higher lighting resolution than the original Light Stage OLAT capture. Although these approaches achieve photorealistic rendering under novel lighting conditions, they only work from fixed viewpoints. (p. 3)

Meka et al. [2020] achieve relightable free viewpoint rendering of dynamic facial performance by extending Meka et al. [2019] with explicit 3D reconstruction and multi-view capture. However, they extract pixel-aligned features from captured raw images under color gradient light illumination to build relightable textures, which limits its usage scenarios to performance replay. In contrast, our approach enables the creation of virtual avatars that not only allows for free viewpoint rendering with a relightable appearance but also possesses the capability of being controlled by an animation sequence of a different subject. (p. 4)

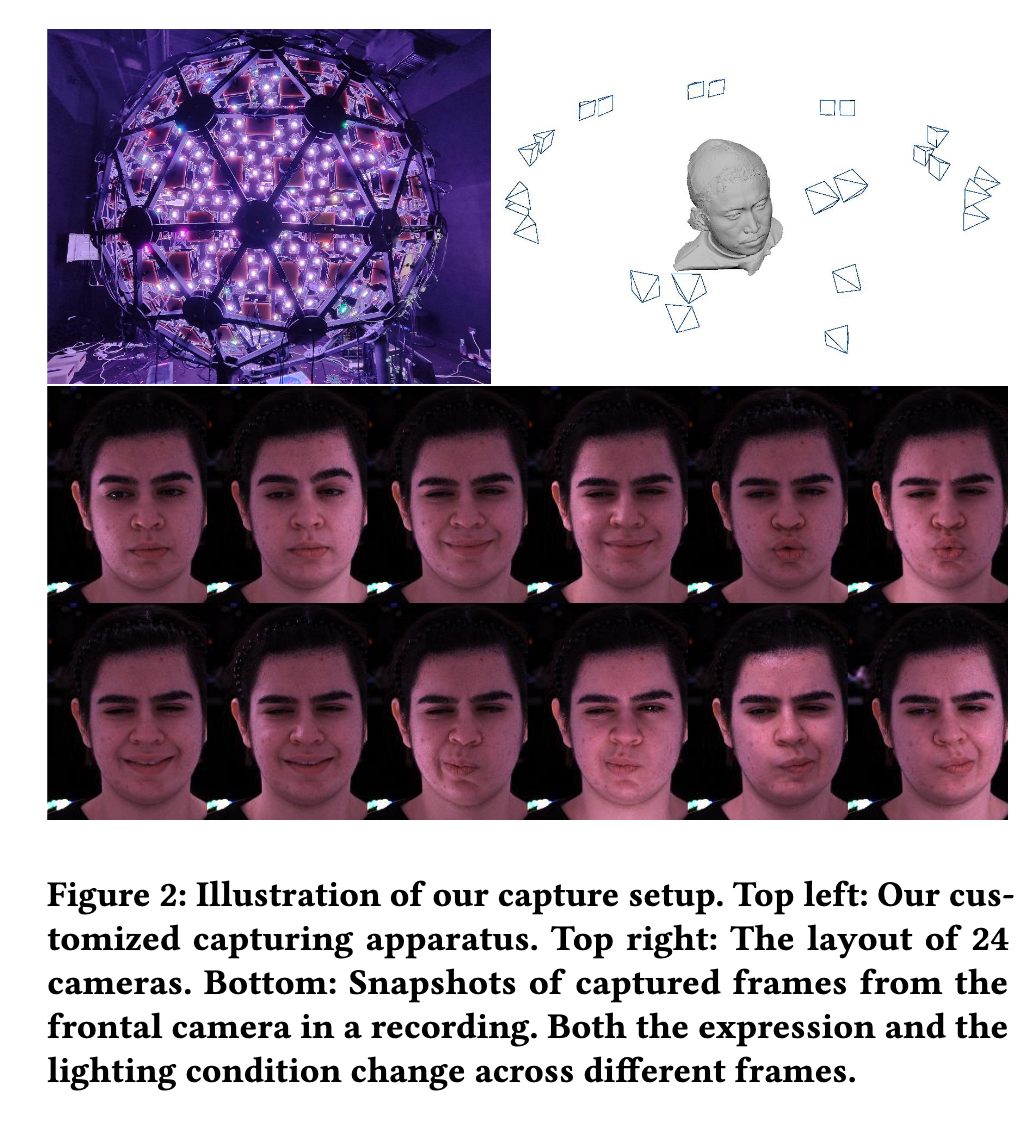

CAPTURING APPARATUS

Lighting units

The 356 lighting units are uniformly mounted on the sphere and are oriented towards the center. Each customized lighting unit comprises 132 high-brightness Light-Emitting Diodes (LEDs) that are controlled by a programmable embedded system. The LEDs are equipped with diffusers and lenses to ensure equal density illumination at the center. (p. 4)

There are five different types of LEDs on the lighting unit, namely red, green, blue, white 4500K, and white 6500K and each type of LED is grouped into three categories with different polarization arrangements. The brightness of each group of lights can be adjusted independently using Pulse Width Modulation up to 100KHz. All the lighting units are connected to a central control unit and a computer via a CAN bus. The lighting pattern can be shuffled within 2ms, allowing us to capture the subject’s performance under various lighting conditions quickly (p. 4)

Cameras

Our apparatus includes 24 machine vision cameras installed around the sphere, with a focus on the center. The cameras consist of four 31M RGB cameras, 12 5M RGB cameras, and eight 12M monochrome cameras. The trigger ports of these cameras are linked to the central control unit, which synchronizes the cameras and lighting units to capture the subject’s performance under various lighting conditions. We have disabled postprocessing features such as automatic gain adjustments in the cameras to ensure a linear response to the illuminance. (p. 4)

We calibrate the camera array with a 250mm calibration sphere similar to [Beeler et al. 2010] and undistort the images to ensure high-quality reconstruction. The mean reprojection error is less than 0.4 pixels, which facilitates high-quality creation of the target avatar. (p. 4)

Method

TRAvatar

Inspired by the success of image based relighting methods, our lighting condition is modeled as a vector 𝑙 ∈ R_+^356 representing the incoming light field of 356 densely sampled directions corresponding to the light positions of the Light Stage. (p. 5)

Specifically, the transformation decoder D_𝑇 : R^256 → R^{9×𝑁_{𝑝𝑟𝑖𝑚}} computes the rotation 𝑅_𝑝 , translation 𝑡_𝑝 , and scale 𝑠_𝑝 of 𝑁_{𝑝𝑟𝑖𝑚} primitives relative to the tangent space of the base mesh, which compensate for the motion that is not modeled by the mesh vertex v. The opacity decoder D_𝛼 : R^256 → R^{𝑀^3×𝑁_{𝑝𝑟𝑖𝑚}} also takes the expression code 𝑧_𝑒 as input and decodes the voxel opacity 𝑉𝛼 of the primitives. The appearance decoder D_𝑟𝑔𝑏 : R^{256+356+3} → R^{3×𝑀^3×𝑁_{𝑝𝑟𝑖𝑚}} takes the expression code 𝑧_𝑒 , the lighting condition 𝑙, and the view direction d as input and predicts the RGB colors 𝑉_𝑟𝑔𝑏 of the primitives. (p. 5)

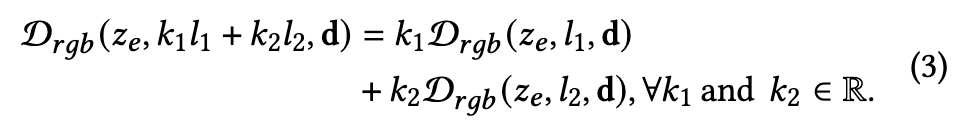

Relightable Appearance

Although the appearance changes drastically when lighting condition changes, previous methods [Basri and Jacobs 2003; Xu et al. 2018] have shown that the relighted images often lie in low-dimensional subspaces. For example, nearly all the lighting effects are linear [Chandrasekhar 2013; Debevec et al. 2000] and the full reflectance field can be predicted from a few images of the object in specific lighting conditions [Meka et al. 2019; Xu et al. 2018]. However, directly predicting all OLAT images and adding them up for environment map relighting is not feasible for real-time rendering. Our key observation is that we can design a network architecture upon the disentangled representation for our appearance decoder D_𝑟𝑔𝑏 to strictly satisfy the linear nature of lighting, i.e.: (p. 5)

The expression code 𝑧_𝑒 and the view direction d are fed into an ordinary non-linear branch. The lighting condition 𝑙 is injected in a separate linear branch, where the activation layers and the bias in the fully connected layer and transposed convolutional layers are removed. The feature maps of the linear branch F_lin is point-wise multiplied with the feature maps from the non-linear branch F_nlin at each stage: (p. 6)

In this way, the appearance decoder D𝑟𝑔𝑏 is strictly linear to the lighting condition 𝑙 while being non-linear to the expression code 𝑧𝑒 and the view direction d that does not limit the representation power (p. 6)

Network Training

Our model is trained end-to-end on the multi-view image sequences under varying illuminations. The training loss L_𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 consists of two parts: L_𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 = L_𝑖𝑚𝑔 + L_𝑟𝑒𝑔, where L𝑖𝑚𝑔 is the data term and L_𝑟𝑒𝑔 is the regularization term. The data term L𝑖𝑚𝑔 contains three components and measures the similarity between the captured input and the rendered output: (p. 6)

where L_1 is the MAE loss, L_VGG is the perceptual loss, and L_GAN is the adversarial loss that improves the visual quality. (p. 6)

The regularization loss L_𝑟𝑒𝑔 comprises four components: (p. 6)

where L_Lap = ||L(v − v_𝑏𝑎𝑠𝑒 )||2 is the expression-aware Laplacian loss to encourage a smooth base mesh. L is the sparse Laplacian matrix. v_𝑏𝑎𝑠𝑒 = B(B^𝑇 B)^{−1}B^𝑇 v is calculated in a least-squares manner based on the 51 predefined expression blendshapes B ∈ R51×3𝑁𝑚𝑒𝑠ℎ from the FaceScape dataset [Yang et al. 2020]. $L_{𝑝𝑅} = \frac{1}{𝑁_{prim}}\lVert(D_𝑇) _{𝑅,𝑡} \rVert$ regularizes the predicted rotation and translation (D_𝑇) _{𝑅,𝑡} to be small. We apply a predefined mask on the base mesh to assign higher weights of L_Lap and L_𝑝𝑅 on facial regions compared to non-facial parts. L_𝑣𝑜𝑙 and L_KLD are the volume minimization prior and KL-divergence loss as in [Lombardi et al. 2021], respectively. 𝜆_Lap, 𝜆_𝑝𝑅, 𝜆_𝑣𝑜𝑙 , and 𝜆_KLD are balancing weights. (p. 6)

Experiment

Ablation Study

We compare four different designs:

- NL: We remove the linear lighting branch of D𝑟𝑔𝑏 and directly feed the concatenated lighting condition 𝑙 and other latent codes to an ordinary non-linear network with the same layers as for appearance prediction. (p. 7)

- NL + ENV: We use the same network architecture as in (1) but use the Light Stage to simulate environment maps [Debevec et al. 2002] instead of group lights for training.

- NL + LCL: We adopt the same network architecture as in (1) and add a lighting consistency loss inspired by the recent single image portrait relighting method [Yeh et al. 2022] to enforce the linearity of lighting.

- NL + TS: We adopt the same network architecture as in (1) and use a two-stage training framework [Bi et al. 2021] for relighting. Specifically, we initially train an appearance decoder D_𝑟𝑔𝑏 for OLAT relighting, and subsequently use the trained network to synthesize data for training the environment map relighting appearance decoder. (p. 8)

Limitation

Despite our promising results, there are some limitations to be addressed in future work. First, the data capturing apparatus employed in our framework is expensive, which may limit its applicability and adoption. Second, due to the lack of sufficient surface constraints, it becomes challenging to perform precise manual control on the learned implicit representation. (p. 8)