Unified Model for Image, Video, Audio and Language Tasks

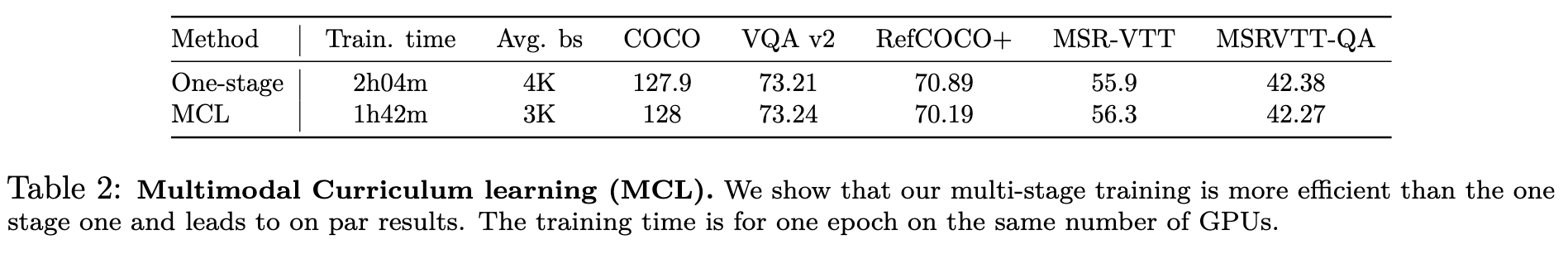

[multimodal deep-learning transformer curriculum-learning multi-task This is my reading note on Unified Model for Image, Video, Audio and Language Tasks. This paper proposes a data and compute efficient method to train multi modality model. It’s based on multi-stage and multi task learning: in each stage new modality will be added and the model will be initialized from previous stage.

Introduction and Related Work

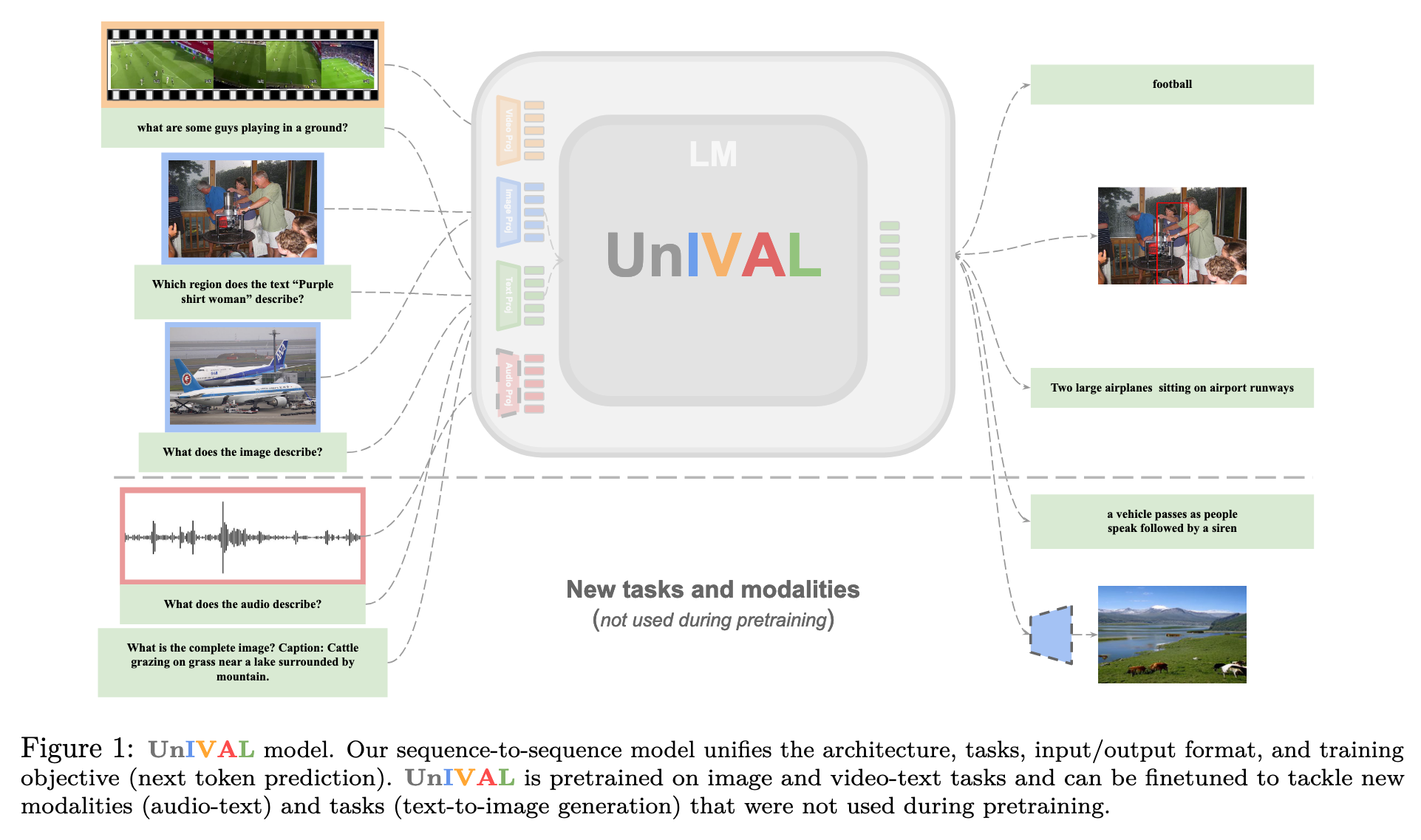

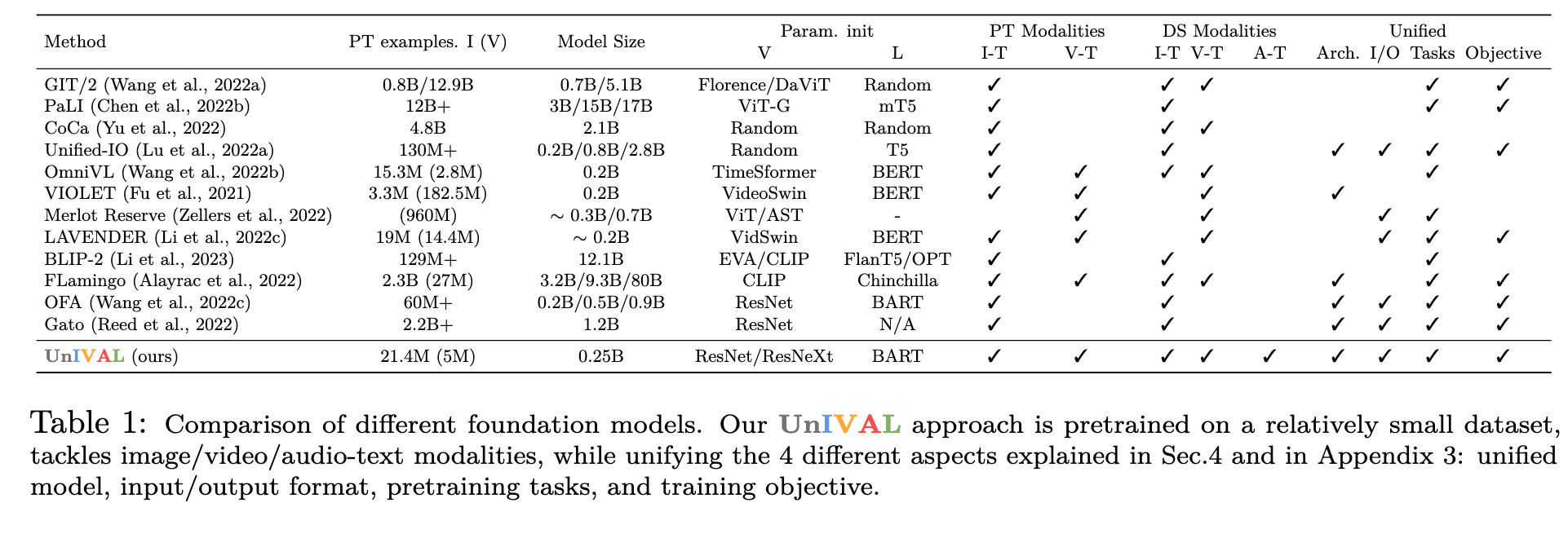

Without relying on fancy datasets sizes or models with billions of parameters, the ∼ 0.25B parameter UnIVAL model goes beyond two modalities and unifies text, images, video, and audio into a single model. Our model is efficiently pretrained on many tasks, based on task balancing and multimodal curriculum learning. UnIVAL shows competitive performance to existing state-of-the-art approaches, across image and video-text tasks. The feature representations learned from image and video-text modalities, allows the model to achieve competitive performance when finetuned on audio-text tasks, despite not being pretrained on audio (p. 1)

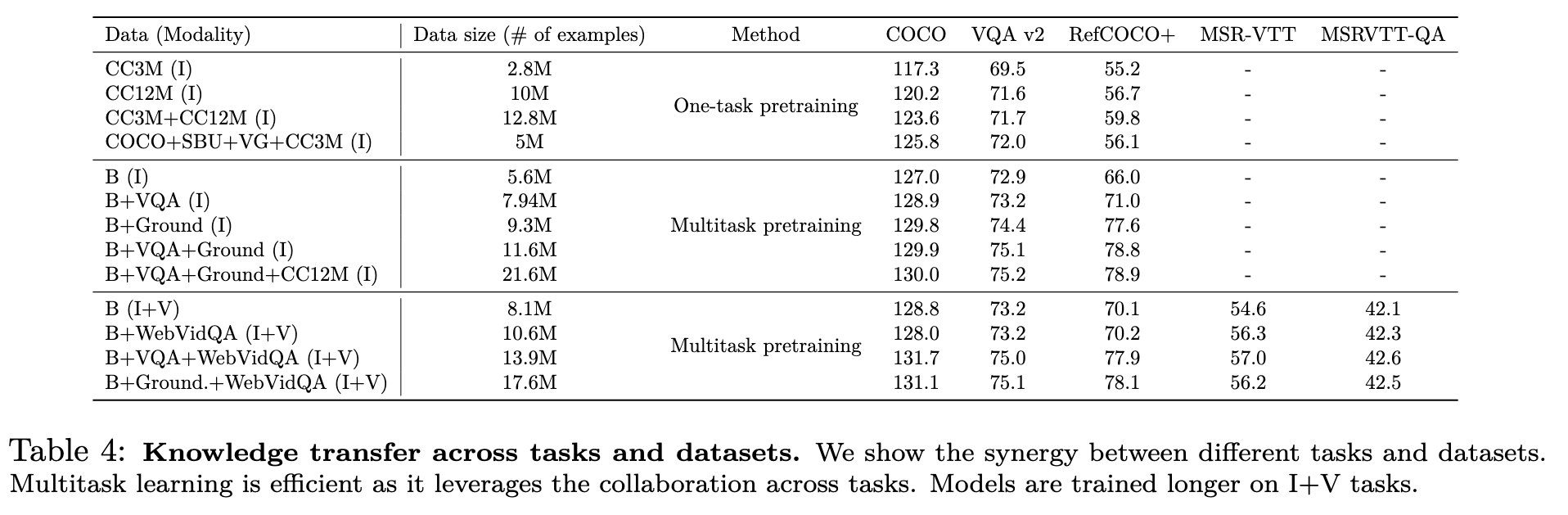

The prevailing approach for pretraining multimodal models revolves around training them on large, noisy image-caption datasets (Schuhmann et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2021; Radford et al., 2021), where the model is tasked with generating or aligning image-captions through causal generation or unmasking. However, this approach encounters a significant challenge: it relies on extensive datasets to compensate for the inherent noise and the relatively simple task of caption generation. In contrast, multitask learning (Caruana, 1997) on relatively small yet high-quality datasets presents an alternative solution to learn efficient models capable of competing with their large-scale counterparts (Alayrac et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2022b; Reed et al., 2022). (p. 2)

Current small to mid-scale (less than couple of hundred million parameters) vision-language models (Li et al., 2019; Shukor et al., 2022; Dou et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022b) still have task-specific modules/heads, many training objectives, and support a very small number of downstream tasks due to the different input/output format. (p. 2)

They have the capability to unify tasks across different modalities, and thus easily supporting new tasks, by representing all inputs and outputs as sequences of tokens, utilizing an unified input/output format and vocabulary. These tokens can represent various modalities such as text, image patches, bounding boxes, audio, video, or any other modality, without the need for task-specific modules/heads. These strategies are straightforward to scale and manage, as they involve a single training objective and a single model (p. 2)

Key contributions:

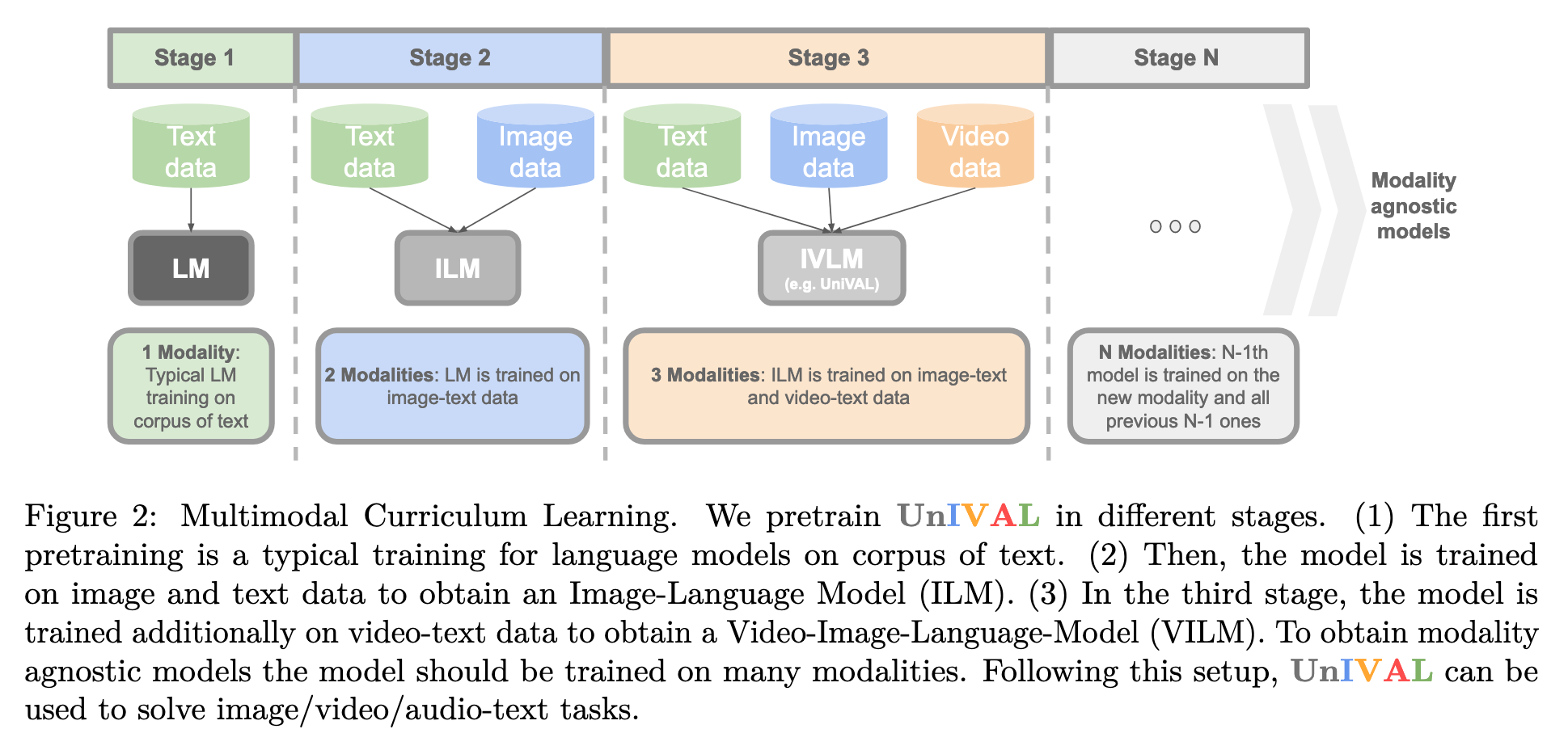

- We show the benefits of multimodal curriculum learning with task balancing, for efficiently training the model beyond two modalities. (p. 2)

- We show the importance of multitask pretraining, compared to the standard single task one, and study the synergy and knowledge transfer between pretrained tasks and modalities. In addition, we find that pretraining on more modalities makes the model generalizes better to new ones. In particular, without any audio pretraining, UnIVAL is able to attain competitive performance to SoTA when finetuned on audio-text tasks. (p. 3)

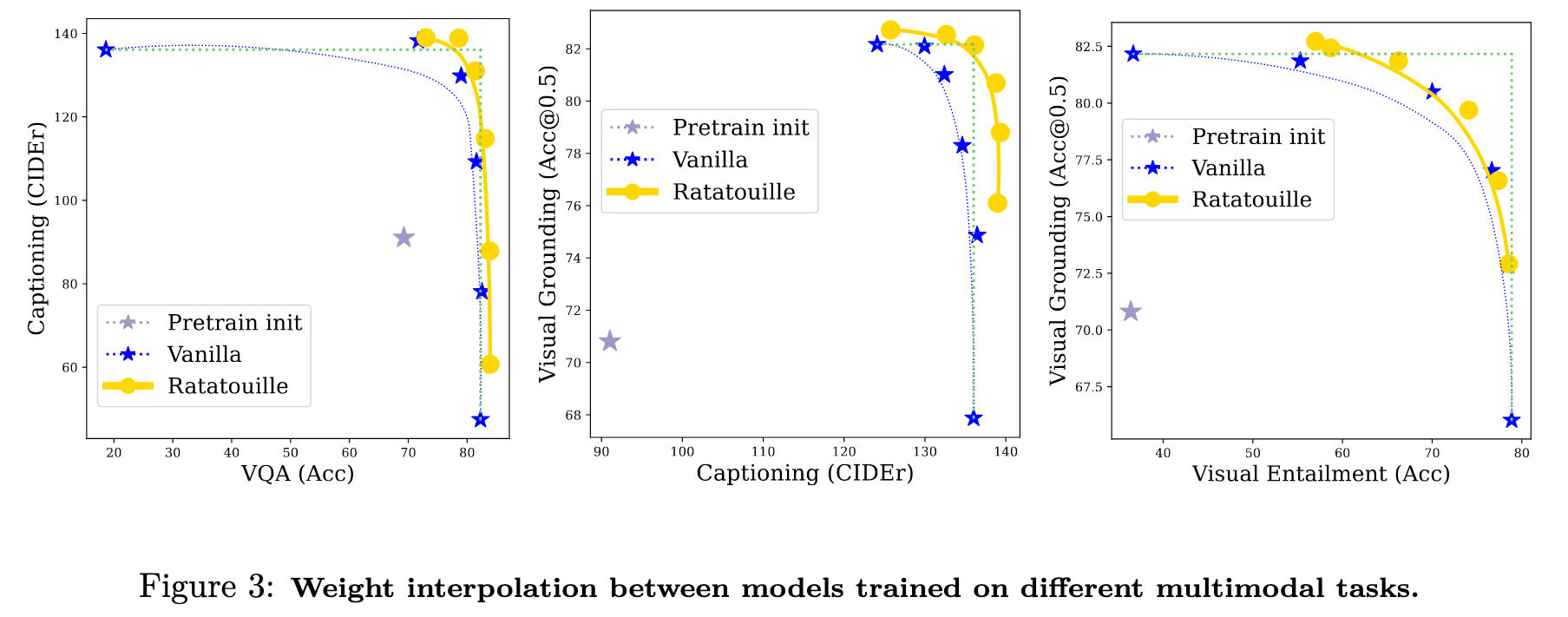

- We propose a novel study on multimodal model merging via weight interpolation (Izmailov et al., 2018; Wortsman et al., 2022; Rame et al., 2022). We show that, when weights are finetuned on different multimodal tasks from our unified pretrained model, interpolation in the weight space can effectively combine the skills of the various finetuned weights, creating more robust multitask models without any inference overhead. Thus, in addition to multitask pretraining, averaging differently finetuned weights is another way to leverage and recycle (Rame et al., 2023a) the diversity of multimodal tasks, enabling their collaboration. This is the first study of weight interpolation showing its effectiveness with multimodal foundation models. (p. 3)

Multimodal pretraining: Contrastive-based approaches (Radford et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2021) try to learn shared and aligned latent space by training on hundreds of millions of pairs. More data-efficient approaches (Shukor et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021a; 2022b; Dou et al., 2021; Singh et al., 2022) relied on additional multimodal interaction modules and variety of training objectives such as image-text matching, masked language modeling and image-text contrastive (p. 3)

Unified models: In the vision community, the work of Chen et al. (2022a), proposed a pixel-to-sequence framework to unify different vision tasks such as object detection and instance segmentation. For multimodal tasks, Cho et al. (2021) proposed to unify vision-language tasks as conditional text generation. OFA (Wang et al., 2022c) then proposed a large-scale sequence-to-sequence framework and extended previous approaches to more image-text tasks, including text-to-image generation. Similarly, Unified-IO (Lu et al., 2022a), in addition to image-text tasks, targets many visual tasks including dense prediction ones. The closest works to us are indeed OFA (Wang et al., 2022c) and Unified-IO (Lu et al., 2022a), however, we propose to unify tasks across more modalities, with significantly smaller model and dataset sizes. The differences are clarified in Tab.1, where we compare different foundation models involving unification. (p. 4)

Weight averaging across multimodal tasks: To combine multiple expert models with diverse special- izations, we leverage a simple yet practical strategy: linear interpolation in the weight space. We follow Ilharco et al. (2023); Daheim et al. (2023); Ortiz-Jimenez et al. (2023) suggesting that averaging networks in weights can combine their abilities without any computational overhead. In particular, this weight averaging (WA) strategy was shown useful in model soups approaches (Wortsman et al., 2022; Rame et al., 2022) to improve out-of-distribution generalization as an approximation of the more costly averaging of predictions. Fusing (Choshen et al., 2022) averages multiple auxiliary weights to serve as an initialization for the unique finetuning on the target task. In contrast, ratatouille (Rame et al., 2023a) delays the averaging after the multiple finetunings on the target tasks: each auxiliary model is finetuned independantly on the target task, and then all fine-tuned weights are averaged. (p. 4)

Background on Unified Foundation Models

Unified input/output. To have a unified model, it is important to have the same input and output format across all tasks and modalities. The common approach is to cast everything to sequence of tokens as in language models. Multimodal outputs can also be discritized, by using VQ-GAN for images and discrete pixel locations for visual grounding. A unified vocabulary is used when training the model. (p. 5)

Unified model. The unified input/output representation allows to use a single model to solve all tasks, without the need to any adaptation when transitioning from the pretraining to the finetuning phase (e.g., no need for task-specific heads). In addition, the current advances in LLMs, especially their generalization to new tasks, make it a good choice to leverage these models to solve multimodal tasks. The common approach is to have a language model as the core model, with light-weight modality-specific input projections. (p. 5)

Unified tasks. To seamlessly evaluate the model on new unseen tasks, it is essential to reformulate all tasks in the same way. For sequence-to-sequence frameworks, this can be done via prompting, where each task is specified by a particular textual instruction. In addition, discriminaive tasks can be cast to generation ones, and thus having only sequence generation output. (p. 5)

Unified training objective. Due to the success of next token prediction in LLMs, it is common to use this objective to train also unified models. An alternative, is to use an equivalent to the MLM loss. The same loss is used during pretraining and finetuning. (p. 5)

Pretraining of UnIVAL

We focus on the challenge of achieving reasonable performance without relying on vast amounts of data. Our approach involves multi-task pretraining on many good-quality datasets. We hope that the quality mitigates the need for massive datasets, thereby reducing computational requirements, while enhancing the model’s generalization capabilities to novel tasks. (p. 5)

Unified model

Our model’s core is a LM designed to process abstract representations. It is enhanced with lightweight modality-specific projections that enable the mapping of different modalities to a shared and more abstract representation space, which can then be processed by the LM. We use the same model during pretraining and finetuning of all tasks, without any task-specific heads. (p. 5)

Shared module. To tackle multimodal tasks at small to mid-scale, we employ an encoder-decoder LM, due to its effectiveness for multimodal tasks and zero-shot generalization after multitask training. Another advantage of this architecture is the inclusion of bidirectional attention mechanisms in addition to unidirectional causal attention. This is particularly beneficial for processing various non-textual modalities. Our model accepts a sequence of tokens representing different modalities as input and generates a sequence of tokens as output. (p. 5)

Light-weight specialized modules. To optimize data and compute requirements, it is crucial to map different modalities to a shared representation space, before feeding them into the encoder of the LM. To achieve this, we employ lightweight modality-specific encoders. Each encoder extracts a feature map, which is then flattened to generate a sequence of tokens. These tokens are linearly projected to match the input dimension of the LM. (p. 5)

In our approach, we opt for CNN encoders (p. 6)

Unified input/output format

The input/output of all tasks consists of a sequence of tokens, where we use a unified vocabulary that contains text, location, and discrete image tokens. (p. 6)

Unified pretraining tasks

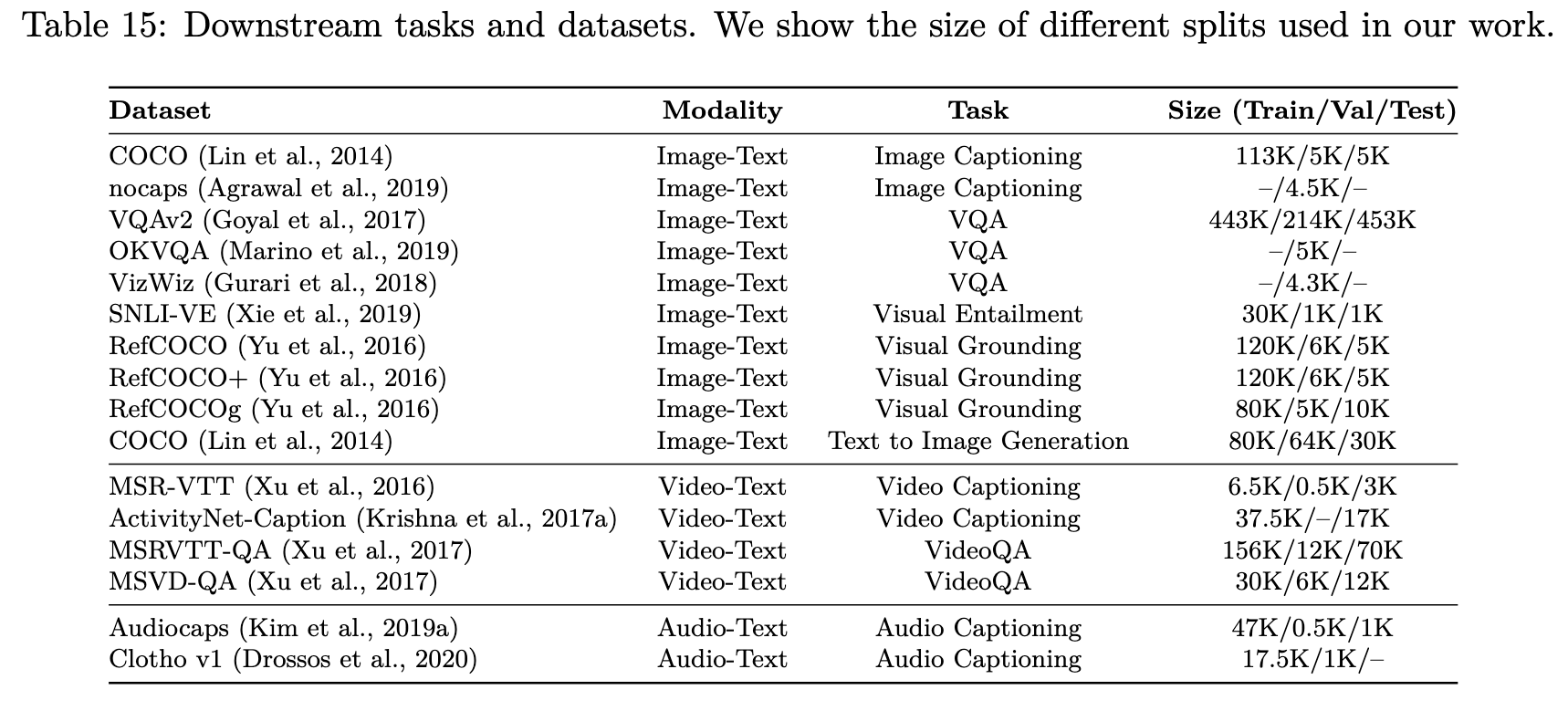

As our model’s core is a LM, we transform all tasks into a sequence-to-sequence format, where each task is specified by a textual prompt. For pretraining tasks, we pretrain only on relatively small public datasets, such as image captioning (COCO (Lin et al., 2014), Visual Genome (VG) (Krishna et al., 2017b), SBU (Ordonez et al., 2011), CC3M (Sharma et al., 2018) and CC12M (Changpinyo et al., 2021) (only in the first stage)), VQA (VQAv2 (Goyal et al., 2017), GQA (Hudson & Manning, 2019), VG (Krishna et al., 2017b)), Visual Grounding (VGround) and referring expression comprehension (RefCOCO, RefCOCO+, RefCOCOg (Yu et al., 2016)), video captioning (WebVid2M (Bain et al., 2021)) and video question answering (WebVidQA (Yang et al., 2021a)) (p. 6)

Unified training objective

We follow other approaches (Wang et al., 2022c; Alayrac et al., 2022) and optimize the model for conditional next token prediction. Specifically, we use a cross-entropy loss. (p. 6)

Efficient pretraining

Other works train the model on all tasks and modalities simultaneously (Wang et al., 2022c; Li et al., 2022c). However, we have observed that models trained on more modalities tend to exhibit better generalization to new ones. To capitalize on this, we employ a different strategy wherein we gradually introduce additional modalities during training (shown in Fig.2). This approach facilitates a smoother transition to new modalities by providing a better initialization. This approach mainly yields gains in training efficiency (p. 7)

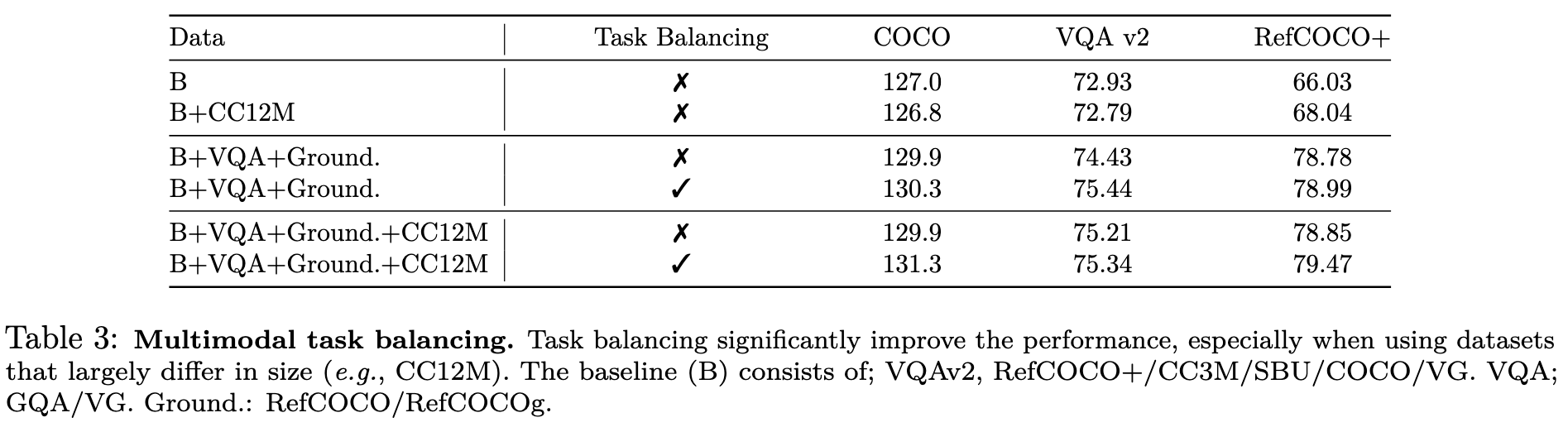

Multimodal task balancing. Contrary to previous work (Wang et al., 2022c), we find it more beneficial to balance the tasks in the batch, especially when using highly unbalanced datasets (p. 7)

Implementation details for pretraining. The architecture of the LM is a typical encoder-decoder transformer initialized by BART-base (Lewis et al., 2020) with few modifications, following the implementation details of other work (Wang et al., 2022c). The modality-specific encoders are ResNet-101 pretrained on ImageNet as image encoder, 3D ResNext-101 (Hara et al., 2018b) pretrained on kinetics 400 as video encoder and PANN encoder pretrained for audio classification as audio encoder, we do not skip the last block as done by previous approaches (Wang et al., 2022c). We use Adam optimizer with weight decay 0.01 and linear decay scheduler for the learning rate starting from 2e − 4. At the end of the last stage, we train the model for additional epoch after increasing the resolution of images from 384 to 480 and the videos from 224 × 224 and 8 frames to 384 × 384 and 16 frames (p. 7)

Weight Interpolation of UnIVAL Models

Then, given two models with weights W1 and W2 finetuned on 2 different tasks among those 4 image-text tasks, we analyze the performance of a new model whose weights are W = λ · W1 + (1 − λ) · W2, where λ ∈ [0, 1]. (p. 12)

Then, by weight interpolation between these two vanilla finetuned endpoints, we reveal a convex front of solutions that trade-off between the different abilities, validating that we can effectively combine the skills of expert models finetuned on diverse multimodal tasks. (p. 12)

In conclusion, these experiments show that uniform averaging can merge different finetuned models to get one general model that performs well on all seen and unseen tasks. Though, results could be improved with tailored selection of the interpolation coefficients λ (p. 13)

Discussion

Despite the good quantitative results, we find that UnIVAL suffers from several limitations. First, UnIVAL can hallucinate. Specifically, it may generate new objects in image descriptions (object bias (Rohrbach et al., 2018)) prioritizing coherence in its generation rather than factuality. Nonetheless, in comparison to other large models like Flamingo (Alayrac et al., 2022), we show in Appendix J that UnIVAL demonstrates a reduced inclination towards hallucinations. This distinction can be attributed to using smaller LM, a component that is known to be particularly susceptible to this issue when scaled. Second, it struggles in complex instruction following. (p. 14)