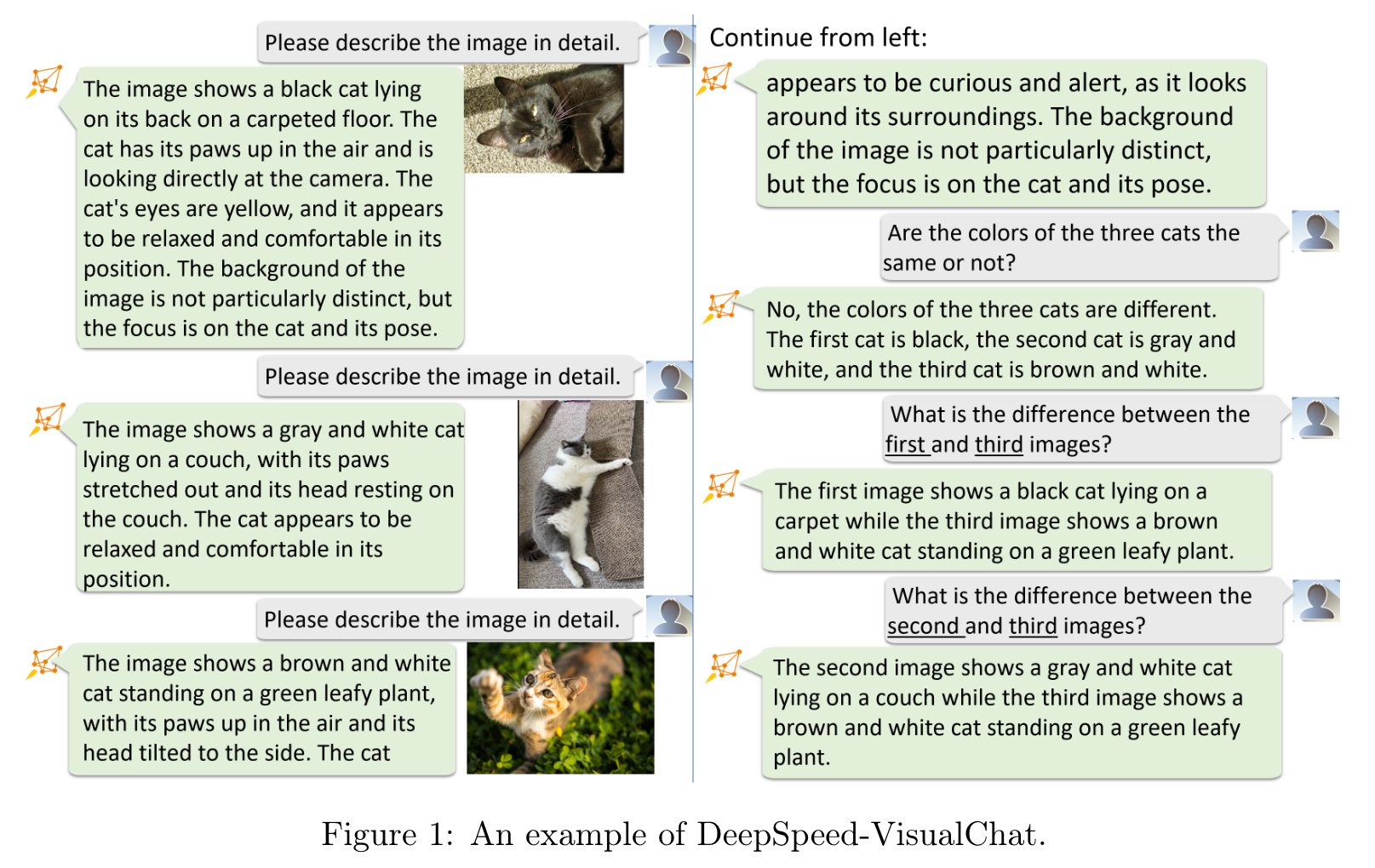

DeepSpeed-VisualChat Multi-Round Multi-Image Interleave Chat via Multi-Modal Causal Attention

[attention chat-gpt qwen-vl clip multimodal llm casual-attention llama mini-gpt4 deep-learning transformer flamingo This is my reading note for DeepSpeed-VisualChat: Multi-Round Multi-Image Interleave Chat via Multi-Modal Causal Attention. This paper proposes a method for multi round multi-image multi modality model. The paper utilizes a frozen LLM and visual encoder. The contribution of the paper includes: 1. Casual cross attention method to combine image and multiround text; 2. A new dataset.

Introduction

To address this, we present the DeepSpeed-VisualChat framework, designed to optimize Large Language Models (LLMs) by incorporating multi-modal capabilities, with a focus on enhancing the proficiency of Large Vision and Language Models in handling interleaved inputs. Our framework is notable for (1) its open-source support for multi-round and multi-image dialogues, (2) introducing an innovative multi-modal causal attention mechanism, and (3) utilizing data blending techniques on existing datasets to assure seamless interactions in multi-round, multi-image conversations (p. 1)

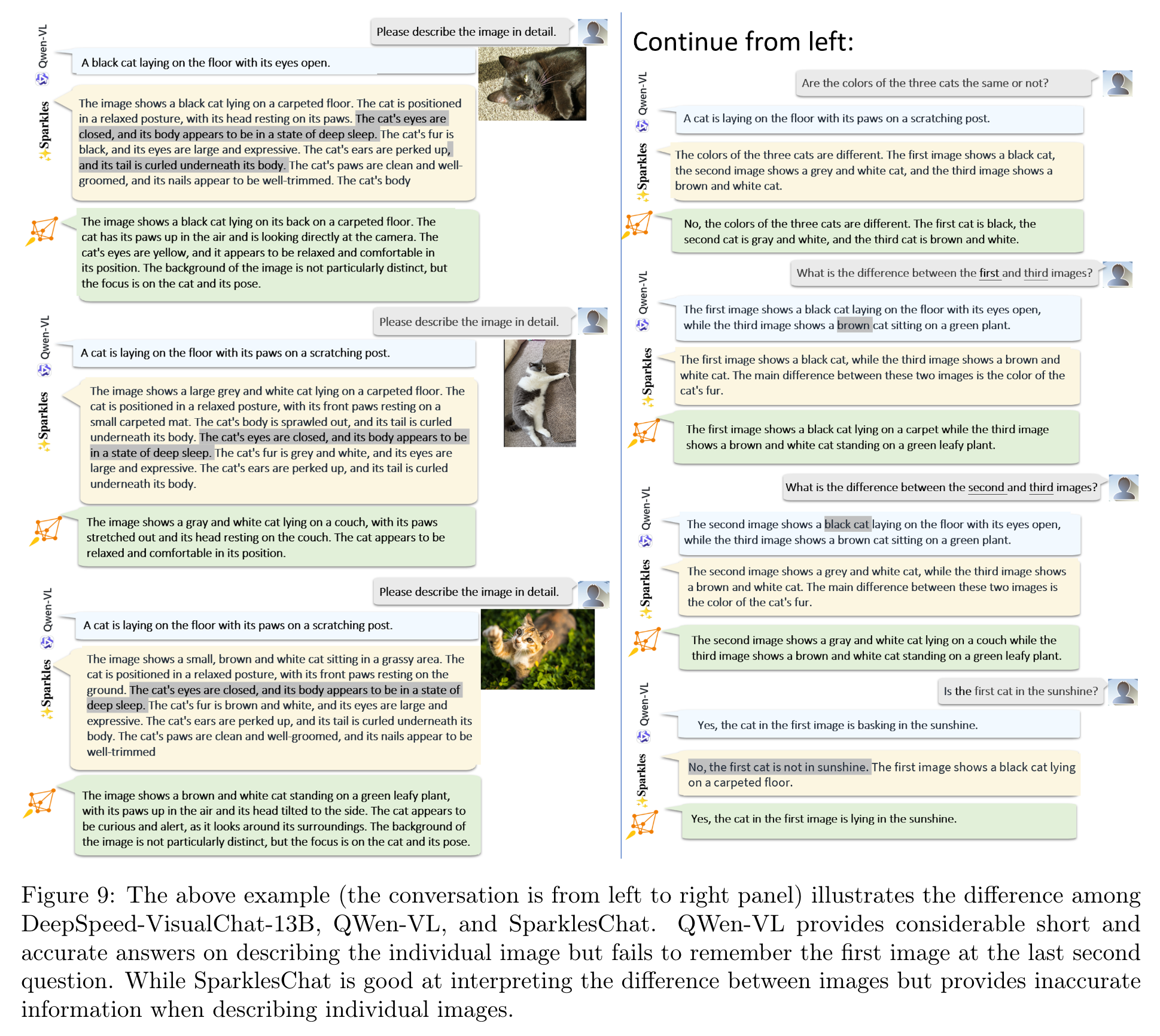

Current frameworks and studies largely focus on either (1) tasks related to individual images, like visual question answering and captioning [23], or (2) handling multiple images but requiring concurrent input [18]. Neither approach adeptly manages interleaved image-and-text inputs. The QWen-VL framework [5], an extension of the LLaVA architecture [23], makes progress in this direction. However, its training costs prove prohibitive for many research labs, and it withholds its training data.

Additionally, in multi-image contexts, their performance is found lacking, even with significant training investments 2, as shown in our comparisons Figure 9. (p. 2)

Related Work

Most implementations of LVLMs deploy one of two architecture styles: (1) The Flamingo design [2, 18, 4] incorporates cross-attention, introducing new parameters to LLMs to interlink visual and textual elements. (p. 3)

Although both designs effectively assimilate visual information and generate textual content, their advantages and drawbacks are manifold. The Flamingo design necessitates extensive training/inference memory and fewer data due to the introduction of numerous new parameters. Conversely, the MiniGPT4 design, while less memory-intensive, is more data-dependent to effectively align visual and textual features. Consequently, an emerging query is whether a novel architecture can harmonize the introduction of fewer new parameters with data efficiency (p. 3)

Method

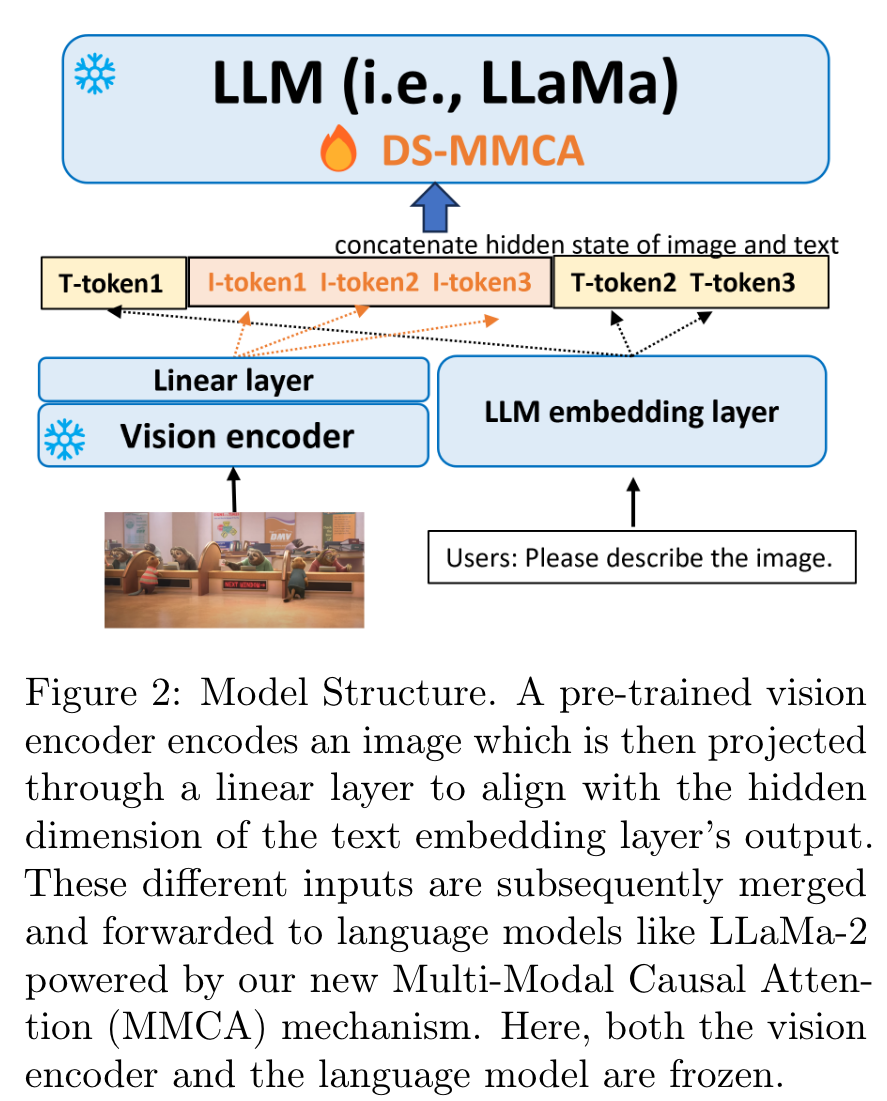

Our model architecture is built on the structure of MiniGPT4 [48, 23], as depicted in Figure 2. Specifically, we maintain the entirety of the visual encoder and the whole language model, with the exception of the embedding layer, in a frozen state. Thus, the only trainable parameters within our model are the visual feature projection layer (a linear layer) and the language model’s embedding. (p. 3)

Diverging from the previous MiniGPT4 architecture, we substitute the conventional causal attention mechanism with our proposed multi-modal causal attention mechanism (refer to Section 4.1). This modification solely alters the computation of causal attention and does not incorporate any new parameters. (p. 3)

Throughout the paper, unless specifically mentioned, we employ the LLaMa-2 family as our language and utilize the extracted (and frozen) visual encoder from QWen-VL [5] as our visual encoder, which accepts 448x448 images and produces 256 image tokens per image. The sequence length for training LLaMa-2 is capped at 4096. (p. 4)

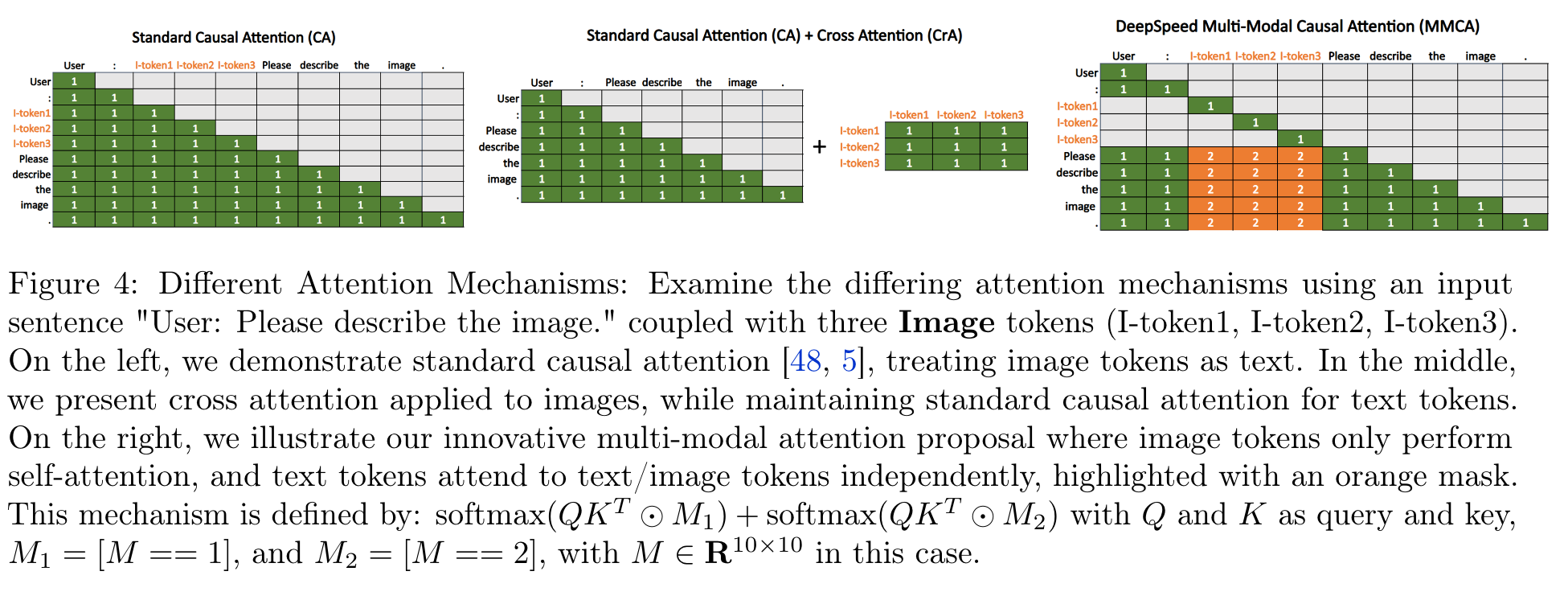

Multi-Round Single-Image Exploration

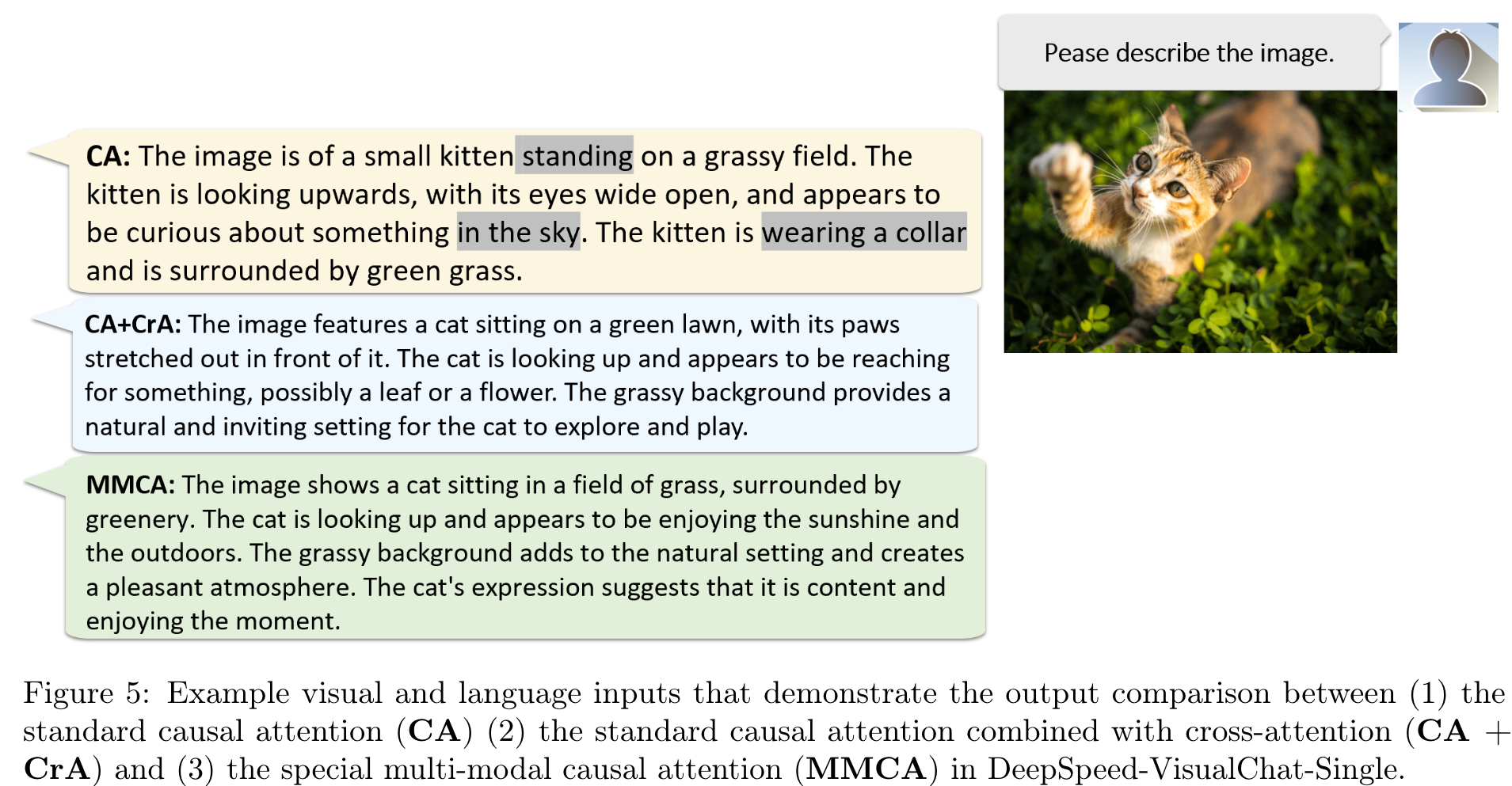

There are two common attention mechanisms used to connect the visual and textual components in a multi-modal model: causal attention, as used in [48, 5], and cross attention, as used in [18, 2]. (p. 4)

Causal Attention (CA)

The CA-based method simply projects visual features (i.e., the features from the output of the final visual encoder layer) into textual features and combines them with the normal textual features after the textual embedding layer to feed into LLMs (p. 5)

- For a visual token, it attends to previous visual and textual tokens, even though visual tokens are already fully encoded in a bidirectional manner and do not need further attention from other visual tokens or the beginning of textual tokens.

- For a textual token, the model needs to learn how to distribute its attention weights between its previous textual and image tokens. Due to these issues, we found that the data efficiency of CA in LVLMs is often problematic. To address this, LLaVA and QWen-VL require visual-language pretraining to fully align visual features with textual features. We also test and compare it with our proposed MMCA in Section 4.2. (p. 5)

Cross Attention (CrA)

The alternative, cross attention (CrA), along with CA, exhibits better data efficiency but also comes with a few drawbacks:

- It introduces new parameters to the model. For example, Otter has more than 1.5 billion trained parameters compared to the millions of trained parameters in LLaVA. This significantly increases the training cost and memory requirements.

- It requires careful design if an image is introduced in the middle of a conversation during training, as previous text tokens should not be able to attend to the image. (p. 5)

Multi-Modal Causal Attention Mechanism (MMCA)

- For visual tokens, they only attend to themselves, as visual tokens are encoded by the visual encoder.

- For textual tokens, they attend to all their previous tokens. However, they have two separate attention weight matrices for their previous textual tokens and image tokens. (p. 5)

Experiment

Other Learning

Better Visual Encoder

Commonly, the CLIP visual encoder is used in LVLMs. However, the CLIP encoder’s resolution is limited to 224x224, which restricts the level of detail in the images. In our testing, we discovered that using the newly released visual encoder from QWen-VL significantly improves the final model quality due to its higher input resolution (448x448) and larger encoder size (2B parameters). (p. 8)

Overfitting or Not

Typically, we select the best evaluation checkpoint or one close to it for final testing. However, during DeepSpeed-VisualChat-Single training, we found that the final checkpoint, even if it appears overfitted, often delivers better testing results compared to middle checkpoints. Does this imply that we should intentionally overfit our model? The answer is no. We experimented with 5, 10, and 20 epochs for DeepSpeed-VisualChat-Single-13B and observed that 10-epoch training typically yields superior final model quality. (p. 8)

Adding LoRA to Visual Encoder or Language Decoder

We attempted to introduce LoRA-based training to enhance model quality. However, applying LoRA to either module did not yield any significant benefits.

Lowering the Learning Rate for Pretrained Components

We experimented with a smaller learning rate for language embedding since it is already pretrained. However, our results indicated that there is no significant difference when using a separate lower learning rate.

Using Chat-/Non-Chat-Based Models

We explored both chat-based and non-chat-based LLama-2 models. Our findings suggest that when using the chat-based model, strict adherence to the chat-based model’s instruction tuning format is crucial. Failing to do so resulted in even worse model quality than the non-chat-based model.

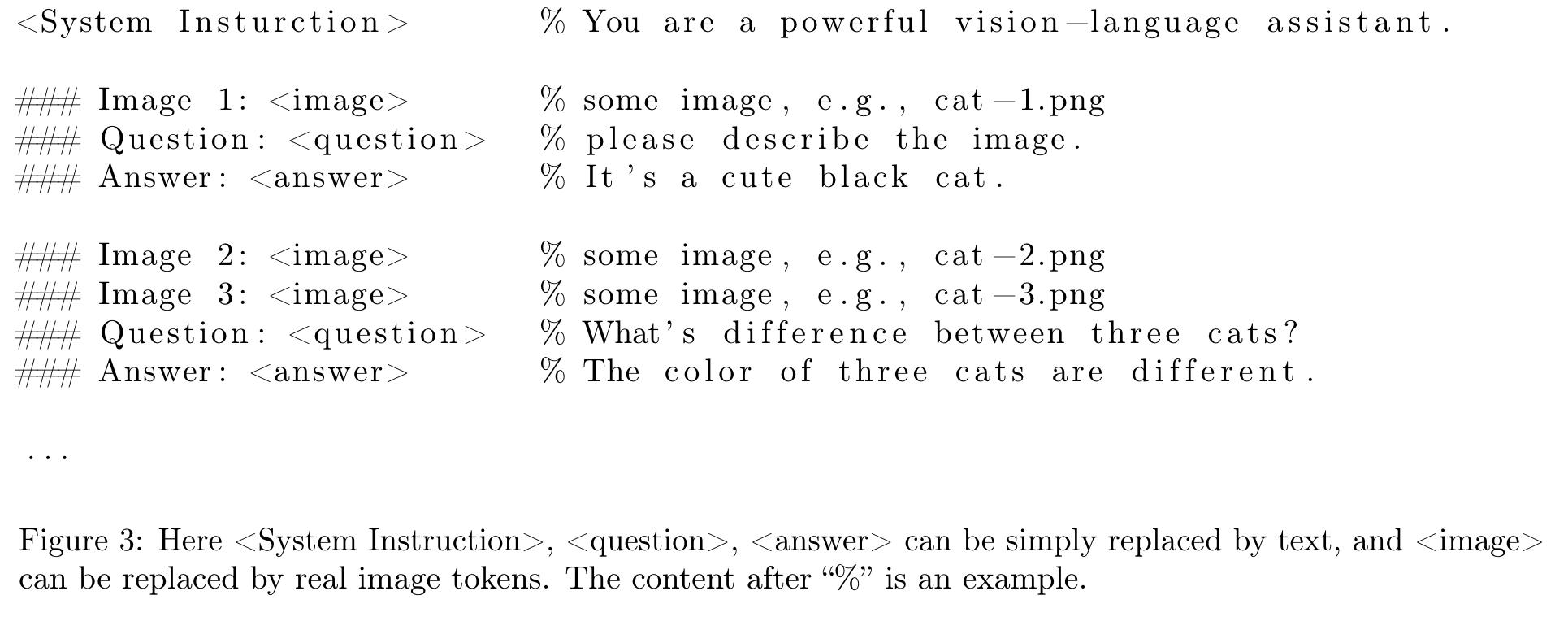

Inserting New Special Tokens or Not

As illustrated in Figure 3, a few tokens can be replaced by new inserted special tokens, such as encoding “###Human: “ as a new special token. However, our testing revealed that it is better not to incorporate them as special tokens. Introducing them as special tokens significantly worsened our generation performance compared to the previous approach. (p. 9)

Multi-Round Multi-Image Exploration

Specifically, we randomly concatenated different numbers of samples into a single sample. (p. 9)

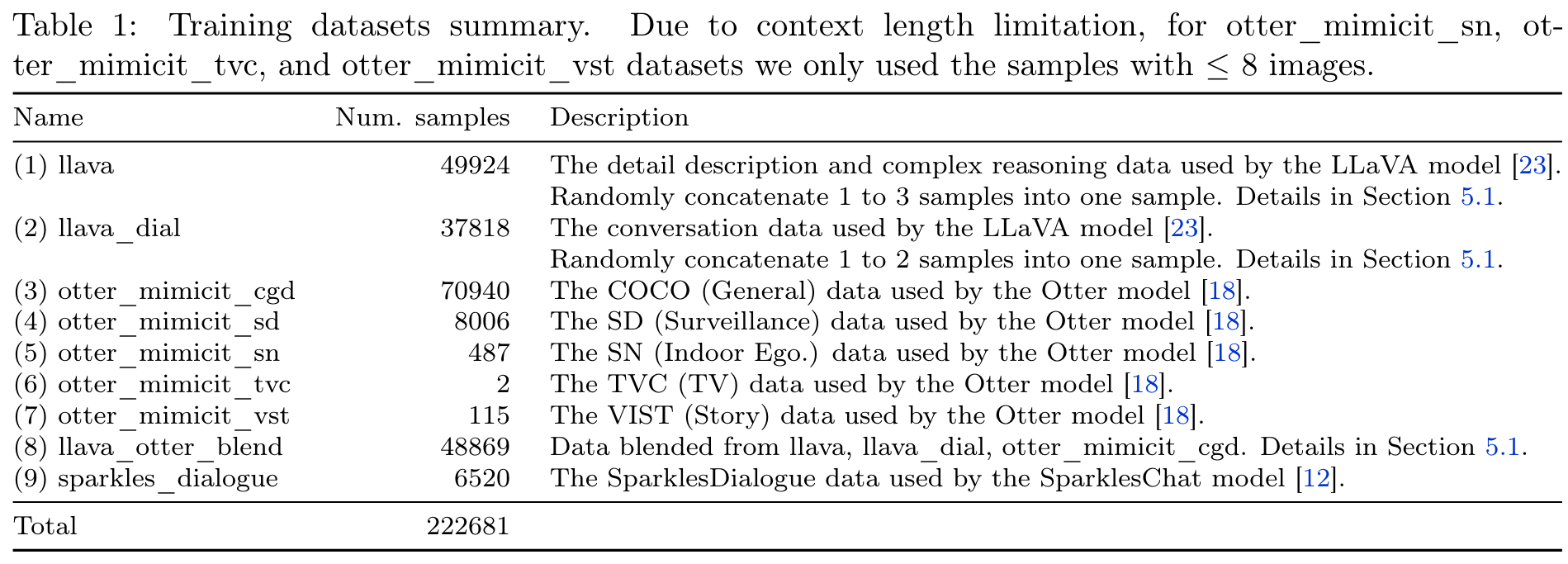

This enables us to build a synthesized multi-round multi-image data llava_otter_blend as a more natural blending: for each sample in the otter_mimicit_cgd dataset, we look for llava and llava_dial samples that use the same image, and then build a new sample in a “llava/llava_dial conversations then otter_mimicit_cgd conversation” fashion (as shown in Table 1). (p. 9)

Experiment

Other Learning

Exploration of Projection Layers

We experimented with two different projection layers to bridge visual encoders and LLMs: a single linear layer and a Vision Transformer layer. We did not observe any benefits from the Vision Transformer approach in the preliminary phase, so we decided not to pursue this route further.

Advanced Data Blending Techniques

We explored more intricate data blending methods, such as shuffling the image ID of the Otter and LLaVA datasets. For example, in the Otter dataset, the paired images were later referenced as the first and third images by inserting another image as the second one. However, our experiments led to deteriorated performance, characterized by incomplete sentences and incorrect references. Upon reviewing the data, we hypothesized that these issues were probably due to incorrect references in the training data during the data blending process. (p. 13)