ELECTRA Pre-training Text Encoders as Discriminators Rather Than Generators

[adversial generator bert spanbert llm gan xlnet discriminator word2vec mass deep-learning electra transformer ernie mask-language-modeling self_supervised unilm This is my reading note ELECTRA: Pre-training Text Encoders as Discriminators Rather Than Generators. This paper proposes to replace masked language modeling with the discriminator task of whether the token is from the authentic data distribution or fixed by the generator model. Especially the model contains a generator that’s trained with masked language modeling objects and discriminator to classify whether a token is filled by the generator or not.

Introduction

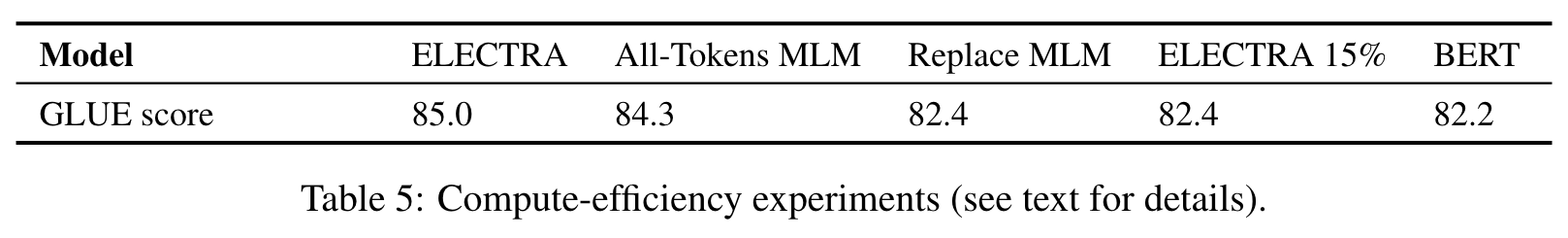

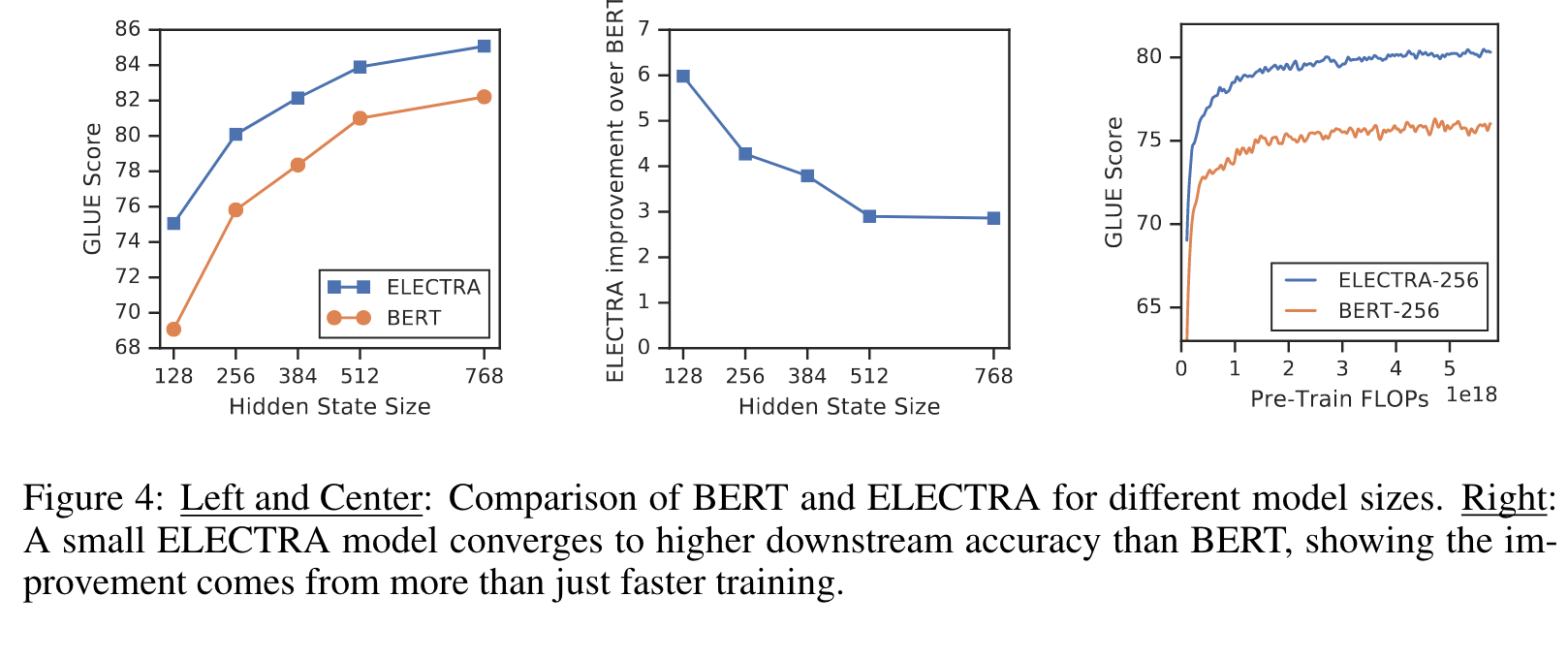

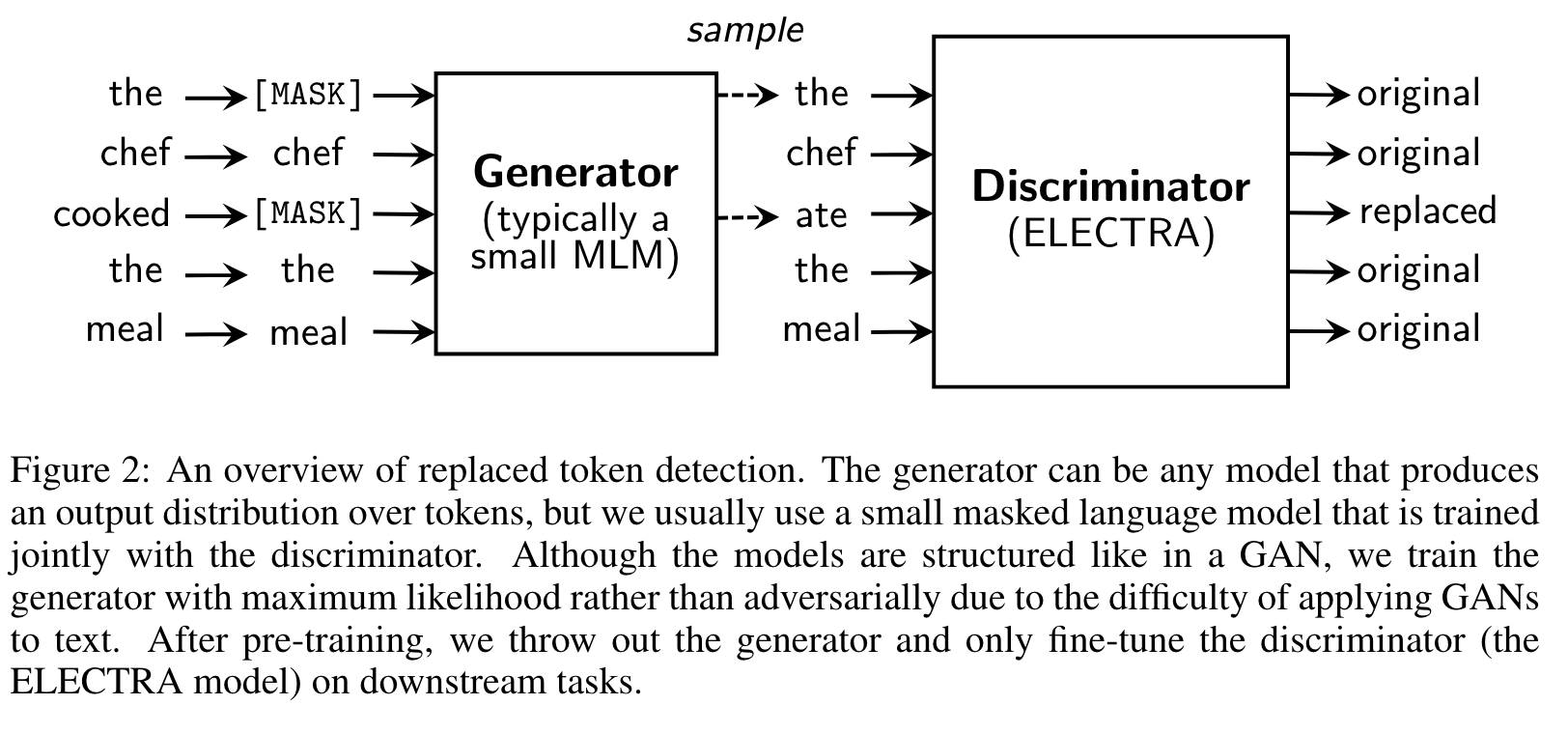

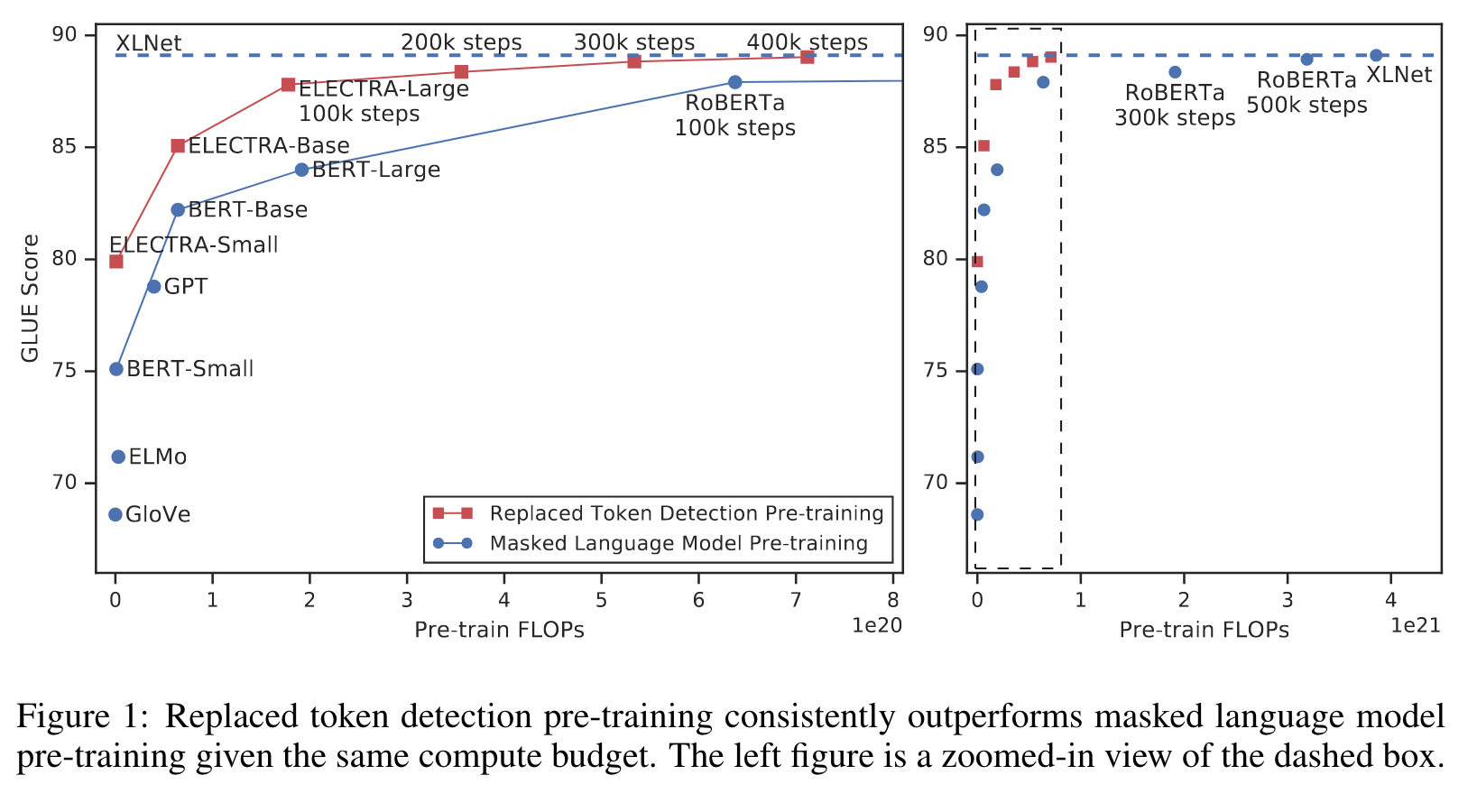

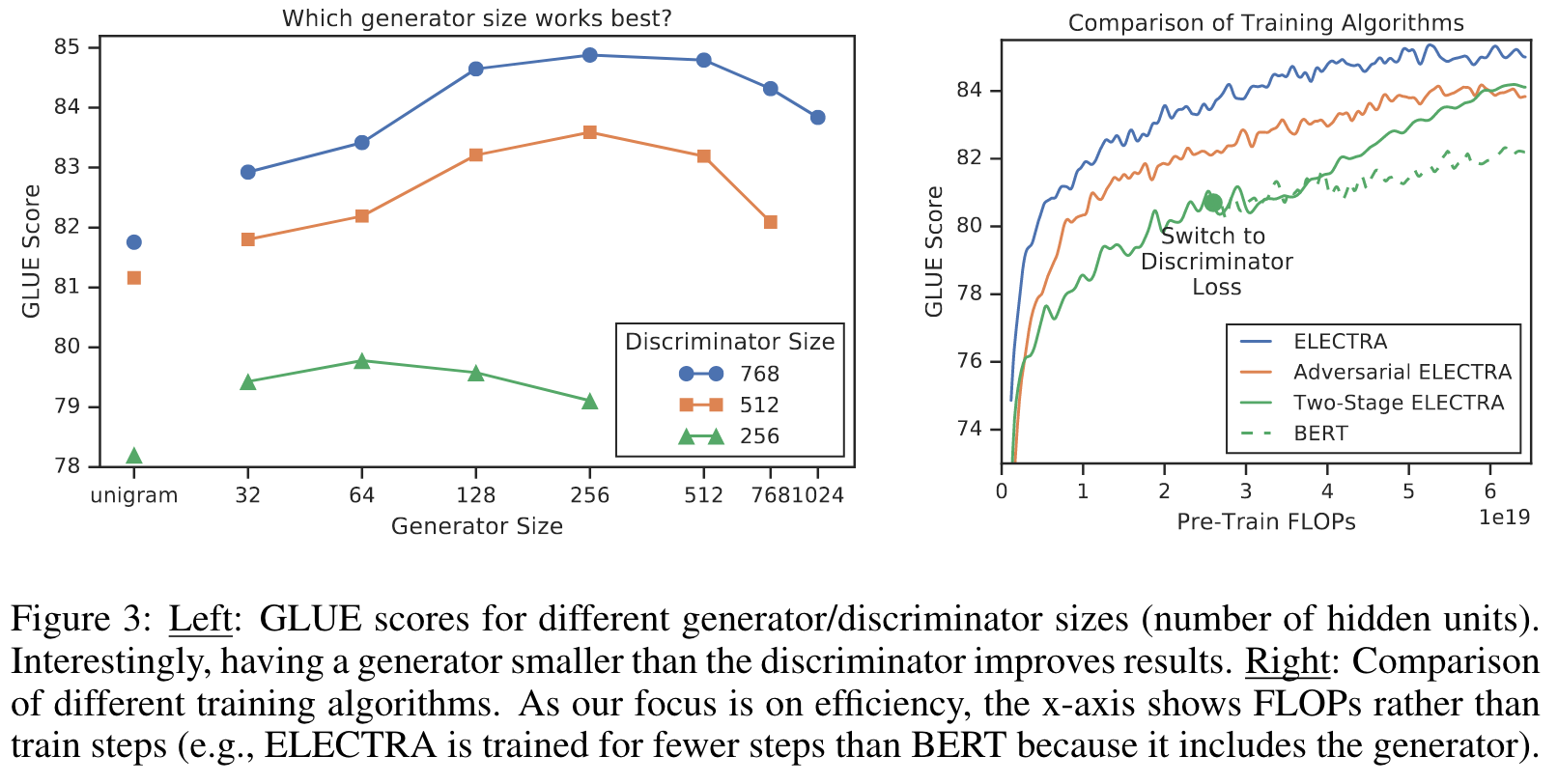

Masked language modeling (MLM) pre-training methods such as BERT corrupt the input by replacing some tokens with [MASK] and then train a model to re- construct the original tokens. While they produce good results when transferred to downstream NLP tasks, they generally require large amounts of compute to be effective. As an alternative, we propose a more sample-efficient pre-training task called replaced token detection. Instead of masking the input, our approach cor- rupts it by replacing some tokens with plausible alternatives sampled from a small generator network. Then, instead of training a model that predicts the original identities of the corrupted tokens, we train a discriminative model that predicts whether each token in the corrupted input was replaced by a generator sample or not. Thorough experiments demonstrate this new pre-training task is more ef- ficient than MLM because the task is defined over all input tokens rather than just the small subset that was masked out. (p. 1)

The gains are particularly strong for small models; for example, we train a model on one GPU for 4 days that outperforms GPT (trained using 30x more compute) on the GLUE natural lan- guage understanding benchmark. (p. 1)

While more effective than conventional language-model pre-training due to learning bidirectional representations, these masked language modeling (MLM) approaches incur a substan- tial compute cost because the network only learns from 15% of the tokens per example. (p. 1)

A key advantage of our discriminative task is that the model learns from all input tokens instead of just the small masked-out subset, making it more computationally efficient. Although our approach is reminiscent of training the discriminator of a GAN, our method is not adversarial in that the generator producing corrupted tokens is trained with maximum likelihood due to the difficulty of applying GANs to text (Caccia et al., 2018). (p. 2)

Related Work

- BERT (Devlin et al., 2019) pre-trains a large Transformer (Vaswani et al., 2017) at the masked-language modeling task (p. 9)

- MASS (Song et al., 2019) and UniLM (Dong et al., 2019) extend BERT to generation tasks by adding auto-regressive generative training objectives.

- ERNIE (Sun et al., 2019a) and SpanBERT (Joshi et al., 2019) mask out contiguous sequences of token for improved span representations (p. 9)

- Instead of masking out input tokens, XLNet (Yang et al., 2019) masks attention weights such that the input sequence is auto- regressively generated in a random order. (p. 9)

Contrastive Learning Broadly, contrastive learning methods distinguish observed data points from fictitious negative samples. (p. 10)

Word2Vec (Mikolov et al., 2013), one of the earliest pre-training methods for NLP, uses contrastive learning. (p. 10)

METHOD

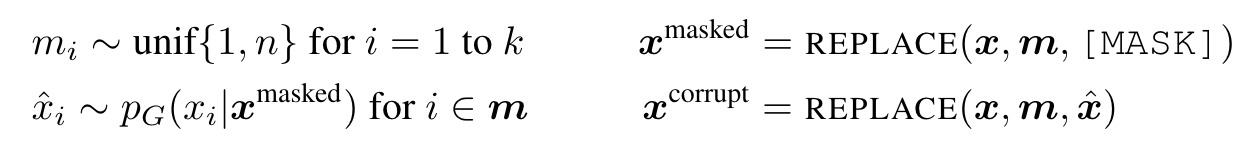

Our approach trains two neural networks, a generator G and a discriminator D. Each one primarily consists of an encoder (e.g., a Transformer network) that maps a sequence on input tokens x = [x_1, …, x_n] into a sequence of contextualized vector representations h(x) = [h_1, …, h_n]. For a given position t, (in our case only positions where x_t = [MASK]), the generator outputs a probability for generating a particular token x_t with a softmax layer (p. 3)

For a given position t, the discriminator predicts whether the token x_t is “real,” i.e., that it comes from the data rather than the generator distribution, with a sigmoid output layer (p. 3)

The generator then learns to predict the original identities of the masked-out tokens. The discriminator is trained to distinguish tokens in the data from tokens that have been replaced by generator samples. (p. 3)

We don’t back-propagate the discriminator loss through the generator (indeed, we can’t because of the sampling step). After pre-training, we throw out the generator and fine-tune the discriminator on downstream tasks. (p. 4)

Comparing with GAN

Although similar to the training objective of a GAN, there are several key differences. First, if the generator happens to generate the correct token, that token is considered “real” instead of “fake”; we found this formulation to moderately improve results on downstream tasks. More importantly, the generator is trained with maximum likelihood rather than being trained adversarially to fool the discriminator. Adversarially training the generator is challenging because it is impossible to back- propagate through sampling from the generator. (p. 3)

Experiment

EXPERIMENTAL SETUP

Our model architecture and most hyperparameters are the same as BERT’s. For fine-tuning on GLUE, we add simple linear classifiers on top of ELECTRA. For SQuAD, we add the question- answering module from XLNet on top of ELECTRA (p. 4)

MODEL EXTENSIONS

Weight Sharing

We propose improving the efficiency of the pre-training by sharing weights be- tween the generator and discriminator. If the generator and discriminator are the same size, all of the transformer weights can be tied. However, we found it to be more efficient to have a small genera- tor, in which case we only share the embeddings (both the token and positional embeddings) of the generator and discriminator. In this case we use embeddings the size of the discriminator’s hidden states.4 The “input” and “output” token embeddings of the generator are always tied as in BERT. (p. 4)

GLUE scores are 83.6 for no weight tying, 84.3 for tying token embeddings, and 84.4 for tying all weights. We hypothesize that ELECTRA benefits from tied token embeddings because masked language modeling is particularly effective at learning these representations: while the discriminator only updates tokens that are present in the input or are sampled by the generator, the generator’s softmax over the vocabulary densely updates all token embeddings. On the other hand, tying all encoder weights caused little improvement while incurring the significant disadvantage of requiring the generator and discriminator to be the same size. Based on these findings, we use tied embeddings for further experiments in this paper. (p. 5)

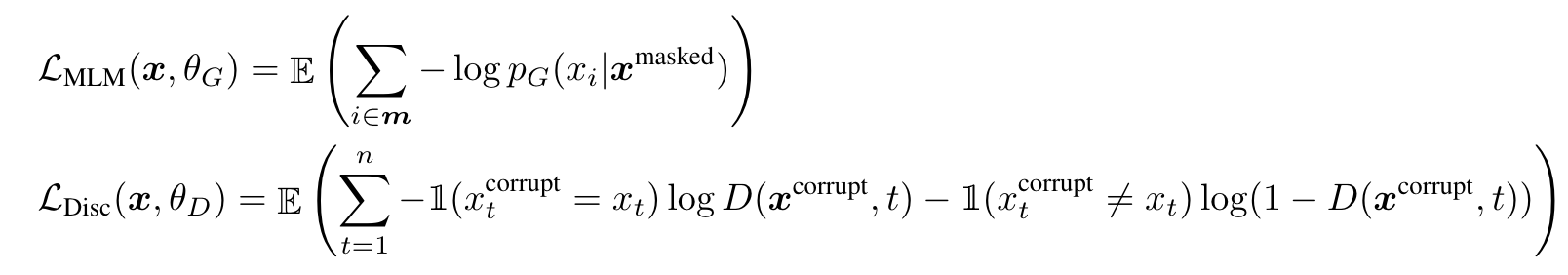

Smaller Generators

If the generator and discriminator are the same size, training ELECTRA would take around twice as much compute per step as training only with masked language mod- eling. We suggest using a smaller generator to reduce this factor. Specifically, we make models smaller by decreasing the layer sizes while keeping the other hyperparameters constant. (p. 5)

Nevertheless, we find that models work best with generators 1/4-1/2 the size of the discriminator. We speculate that having too strong of a generator may pose a too-challenging task for the discriminator, preventing it from learning as effectively. In particular, the discriminator may have to use many of its parameters modeling the generator rather than the actual data distribution. (p. 5)

Training Algorithms

We found that without the weight initialization the discriminator would some- times fail to learn at all beyond the majority class, perhaps because the generator started so far ahead of the discriminator. Joint training on the other hand naturally provides a curriculum for the dis- criminator where the generator starts off weak but gets better throughout training. (p. 5)

Although still outperforming BERT, we found adversarial training to underperform maximum-likelihood training. Further analysis suggests the gap is caused by two problems with adversarial training. First, the adversarial generator is simply worse at masked lan- guage modeling; it achieves 58% accuracy at masked language modeling compared to 65% accuracy for an MLE-trained one. We believe the worse accuracy is mainly due to the poor sample efficiency of reinforcement learning when working in the large action space of generating text. Secondly, the adversarially trained generator produces a low-entropy output distribution where most of the proba- bility mass is on a single token, which means there is not much diversity in the generator samples. Both of these problems have been observed in GANs for text in prior work (Caccia et al., 2018). (p. 6)

Small Models

Starting with the BERT-Base hyperparameters, we shortened the sequence length (from 512 to 128), reduced the batch size (from 256 to 128), reduced the model’s hidden dimension size (from 768 to 256), and used smaller token embeddings (from 768 to 128). (p. 6)

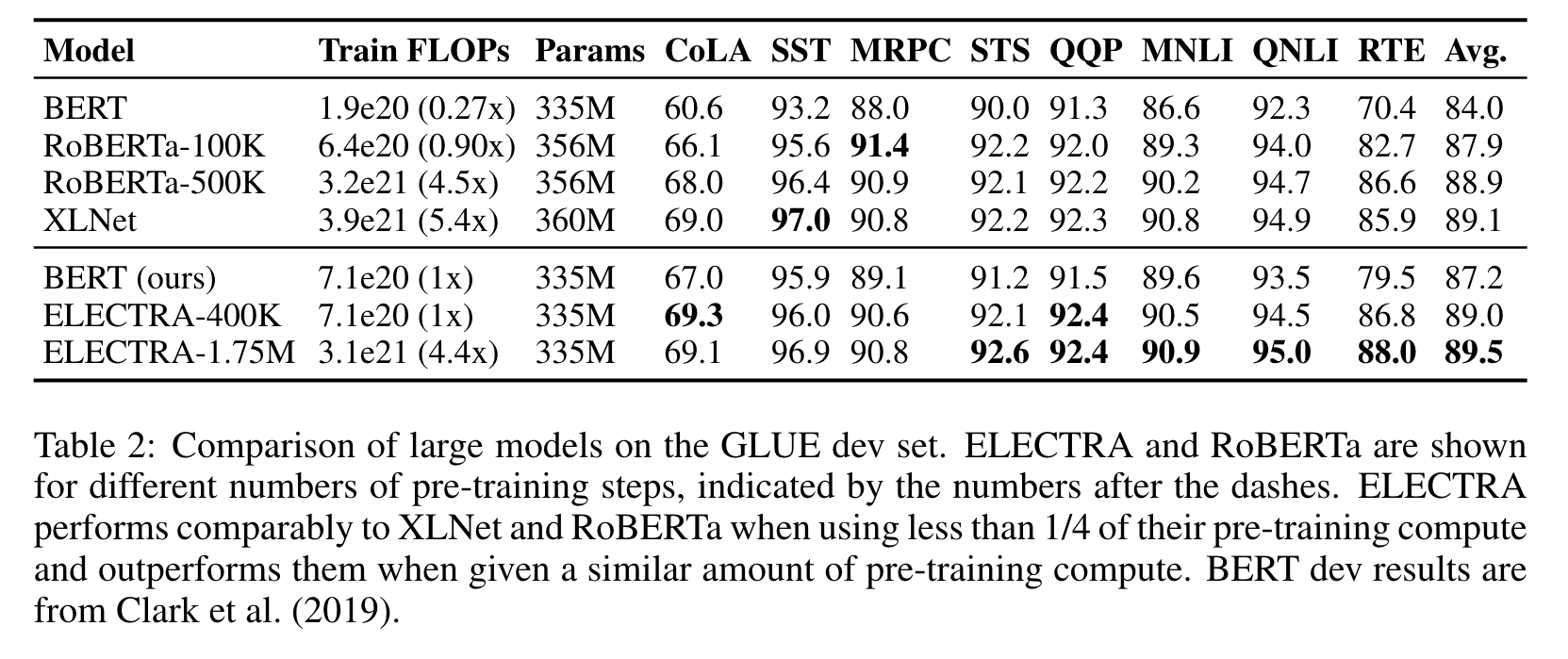

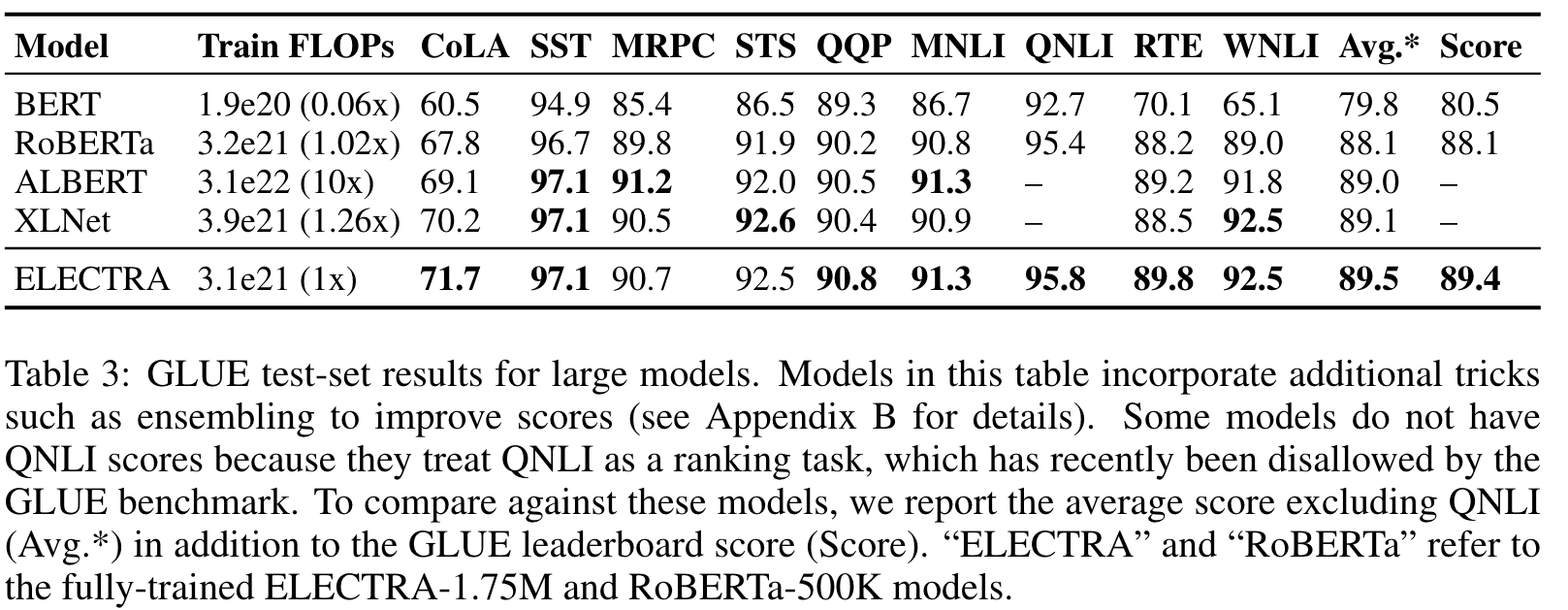

LARGE MODELS

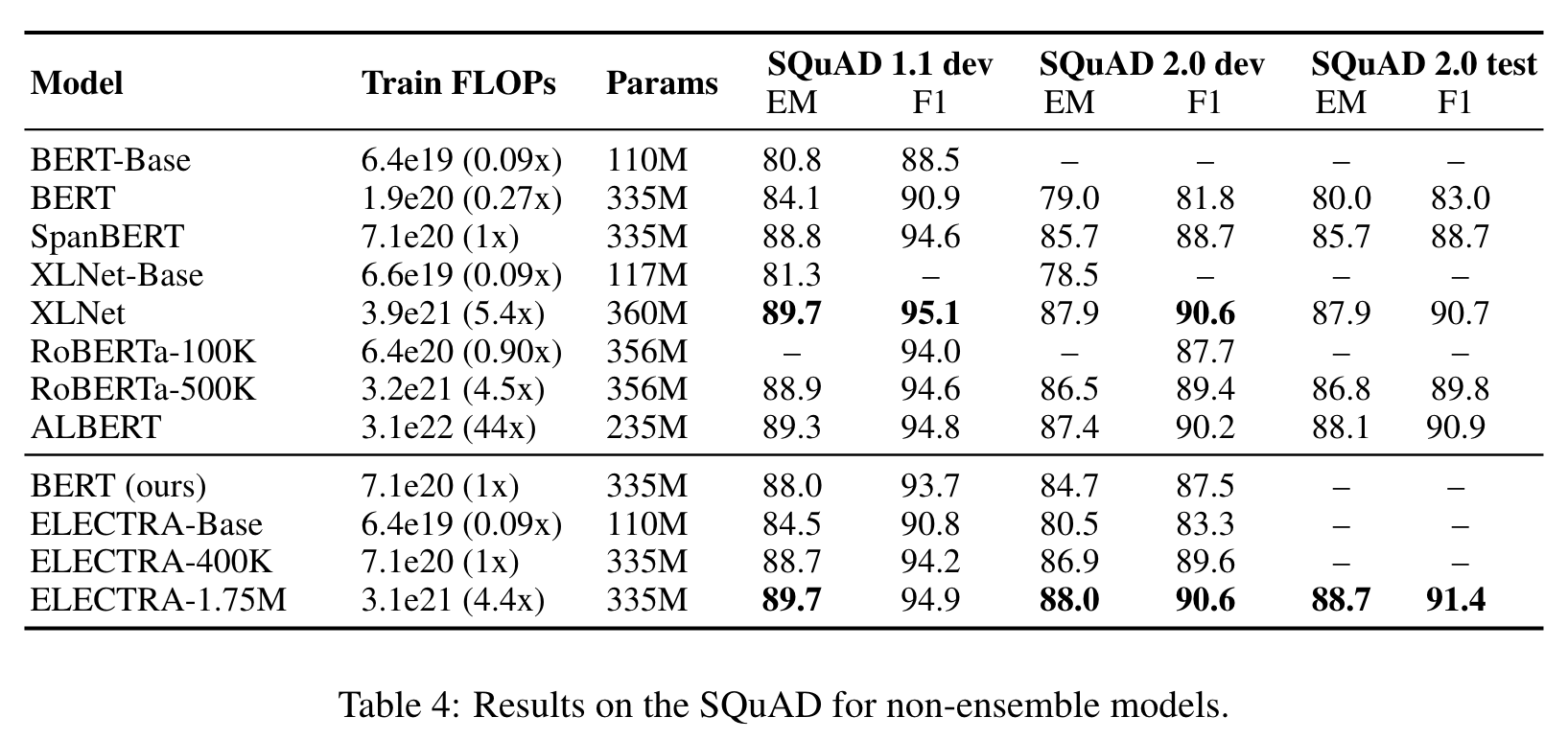

EFFICIENCY ANALYSIS