FLAVA A Foundational Language And Vision Alignment Model

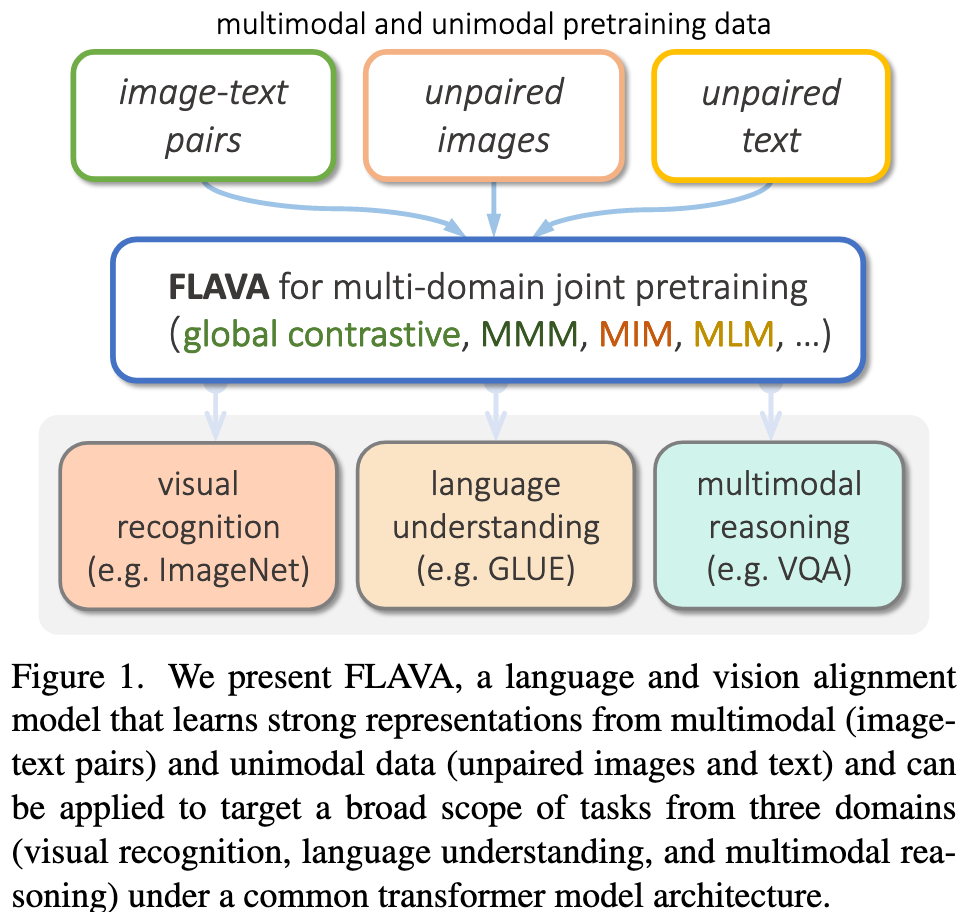

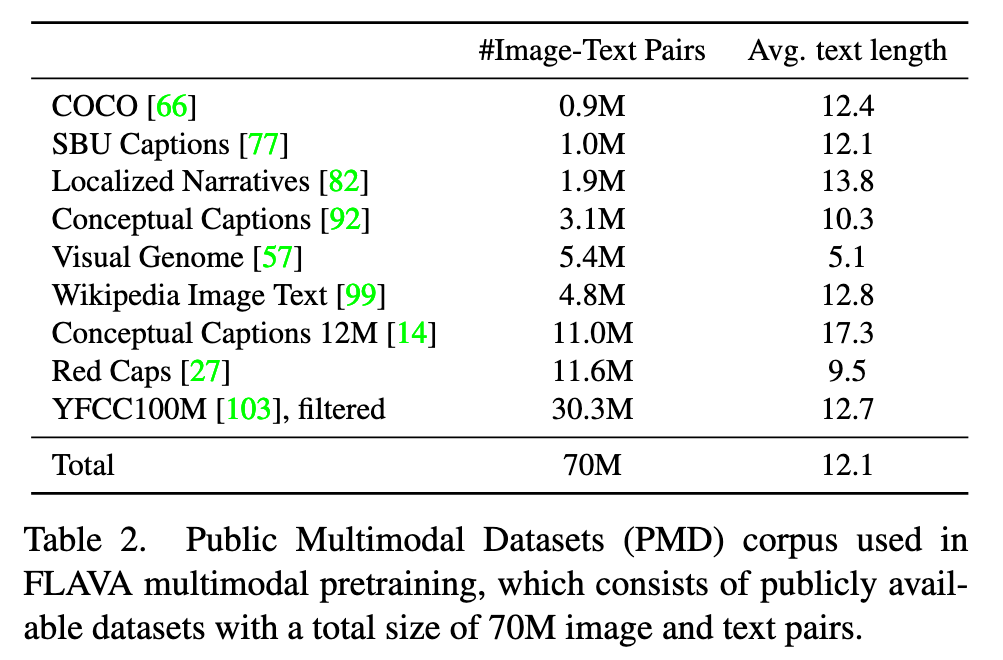

[bert masked-language-modeling clip simvlm multimodal vit masked-image-modeling deep-learning constrast-loss image-text-matching transformer This is my reading note for FLAVA: A Foundational Language And Vision Alignment Model. This paper proposes a multi modality model. Especially, the model not only work across modality, but also on each modality and joint modality. To do that, it contains loss functions for both within modality but also across modality. It also proposes to use the same architecture for vision encoder, Text encoder as well as multi -modality encoder.

Introduction

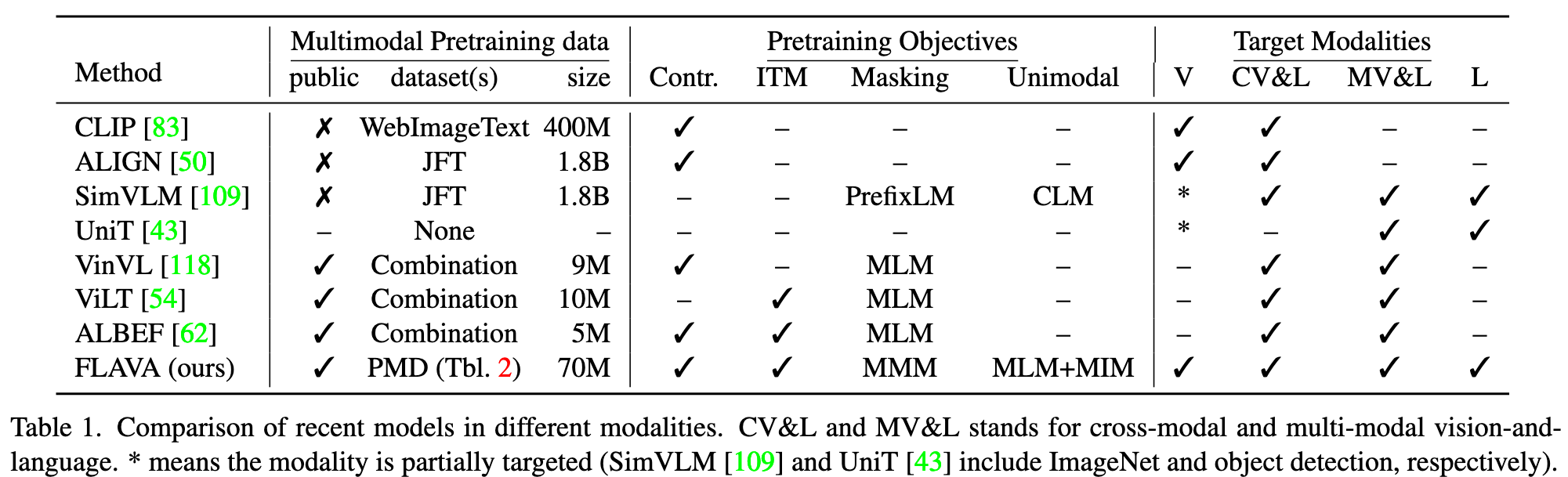

Purely contrastive methods, however, also have important shortcomings. Their cross-modal nature does not make them easily usable on multimodal problems that require dealing with both modalities at the same time. (p. 1)

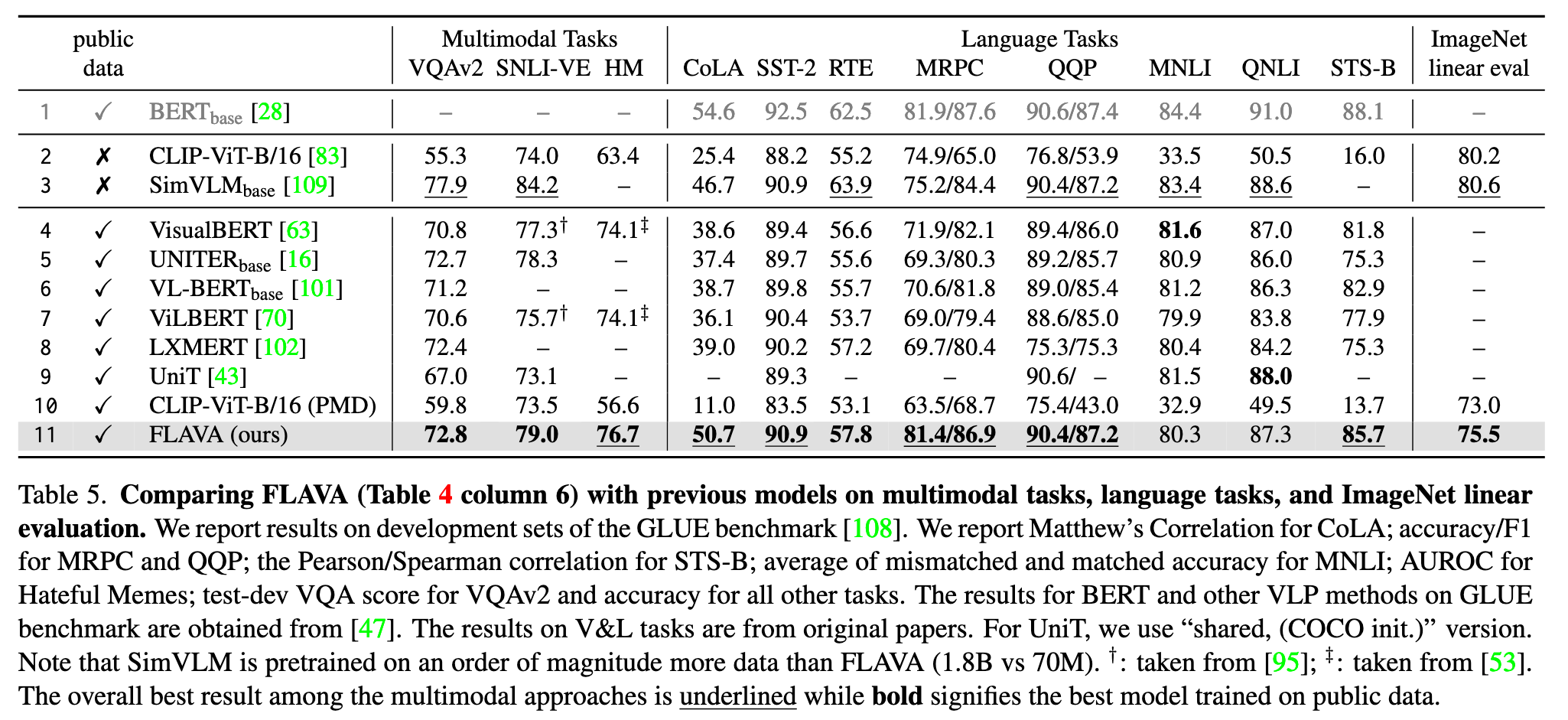

In contrast, the recent literature is rich with transformer models that explicitly target the multimodal vision-and language domain by having earlier fusion and shared self attention across modalities. For those cases, however, the unimodal vision-only or language-only performance of the model is often either glossed over or ignored completely. (p. 1)

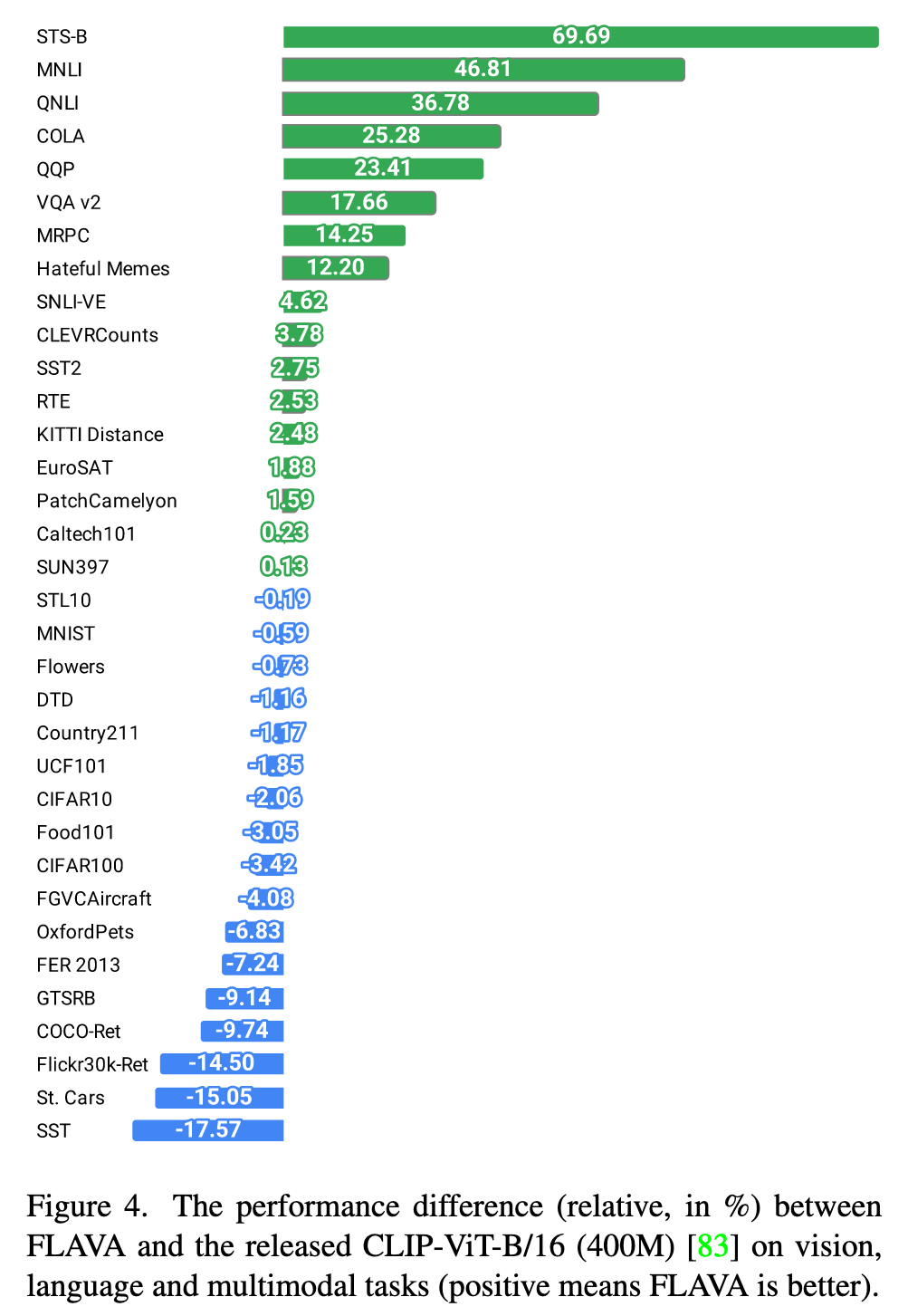

a true foundation model in the vision and language space should not only be good at vision, or language, or vision-and-language problems–it should be good at all three, at the same time. (p. 1)

FLAVA learns strong representations through joint pretraining on both unimodal and multimodal data while encompassing cross-modal “alignment” objectives and multimodal “fusion” objectives. (p. 1)

Background

Generally, models in the vision-and-language space can be divided into two categories: (i) dual encoders where the image and text are encoded separately followed by a shallow interaction layer for downstream tasks [50, 83]; and (ii) fusion encoder(s) with self-attention spanning across the modalities [16, 34, 44, 45, 62–65, 70, 71, 101, 102, 109, 118, 120]. The dual encoder approach works well for unimodal [107, 108] and cross-modal retrieval tasks [66, 81] but their lack of fusion usually causes them to underperform on tasks that involve visual reasoning and question answering [39, 53, 93, 96] which is where models based on fusion encoder(s) shine. (p. 2)

Within the fusion encoder category, a further distinction can be made as to whether the model uses a single transformer for early and unconstrained fusion between modalities (e.g., VisualBERT, UNITER, VLBERT, OSCAR [16, 63, 65, 101, 120]) or allows cross-attention only in specific co-attention transformer layers while having some modality specific layers (e.g., LXMERT, ViLBERT, ERNIE-ViL [70, 71, 102, 116]. Another distinguishing factor between different models lies in the image features that are used, ranging from region features [63, 70, 118], to patch embeddings [54, 62, 109], to convolution or grid features [46, 51].

Dual encoder models use contrastive pretraining to predict the correct N paired combinations among N2 possibilities. On the other hand, with fusion encoders, inspired by unimodal pretraining schemes such as masked language modeling [28, 68], masked image modeling [5], and causal language modeling [84], numerous pretraining tasks have been explored: (i) Masked Language Modeling (MLM) for V&L where masked words in the caption are predicted with help of the paired image [63, 70, 102]; (ii) prefixLM, where with the help of an image, the model tries to complete a caption [26, 109]; (iii) image-text matching, where the model predicts whether given pair of image and text match or not; and (iv) masked region modeling, where the model regresses onto the image features or predicts its object class. (p. 2)

FLAVA: A Foundational Language And Vision Alignment Model

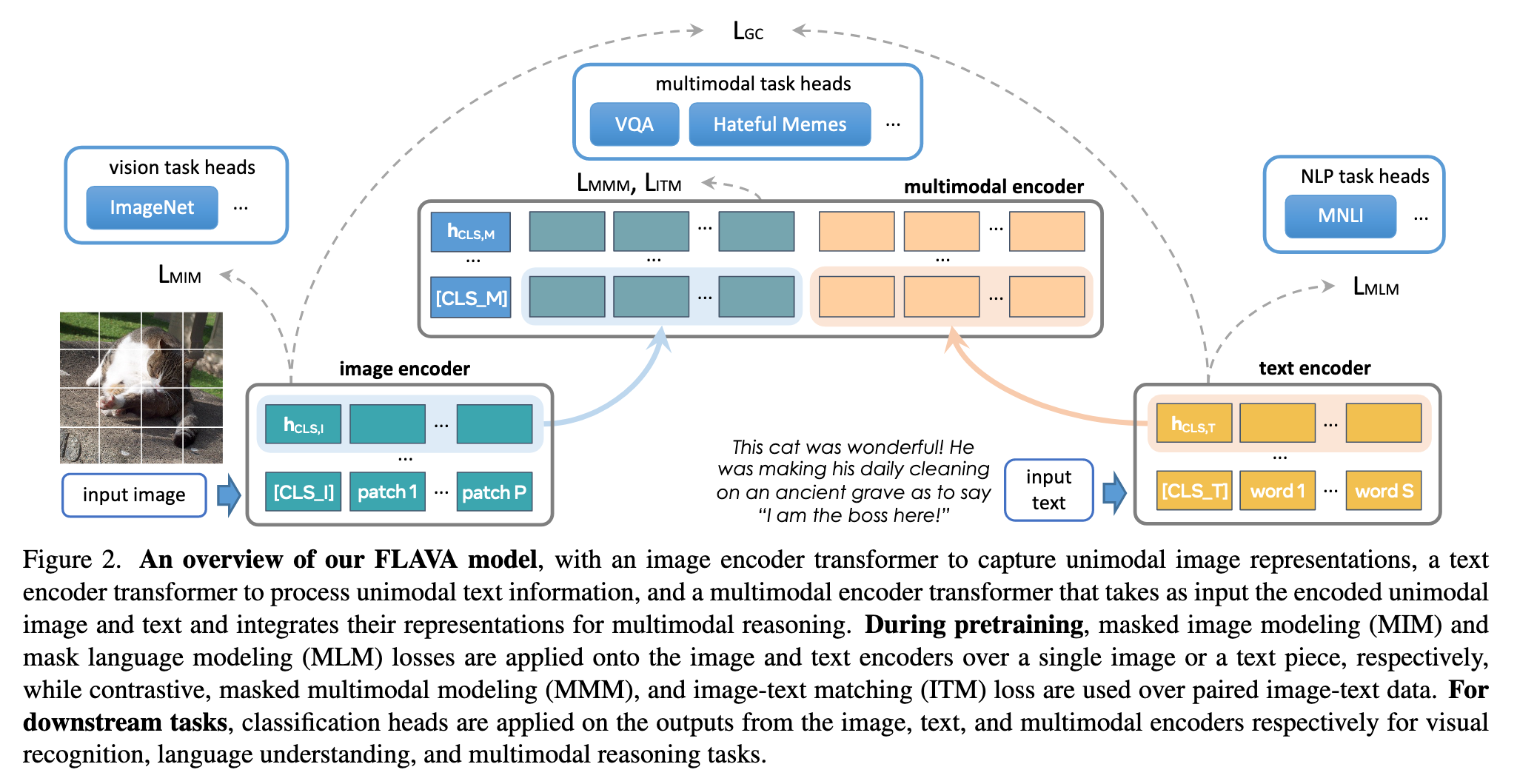

The model architecture

The FLAVA model architecture is shown in Figure 2. The model involves an image encoder to extract unimodal image representations, a text encoder to obtain unimodal text representations, and a multimodal encoder to fuse and align the image and text representations for multimodal reasoning, all of which are based on transformers. (p. 3)

Image encoder

We adopt the ViT architecture [31] for the image encoder. Given an input image, we resize it to a fixed image size and split the image into patches, which are then linearly embedded and fed into a transformer model (along with positional embeddings and an extra image classification token [CLS I]). The image encoder output is a list of image hidden state vectors {hI }, each corresponding to an image patch, plus an additional hCLS,I for [CLS I]. We use the ViT-B/16 architecture for our image encoder. (p. 3)

Text encoder

Given an input piece of text (e.g., a sentence or a pair of sentences), we first tokenize and embed it into a list of word vectors following [28]. Then, we apply a transformer model over the word vectors to encode them into a list of hidden state vectors {hT }, including hCLS,T for the text classification [CLS T] token. Importantly, different from prior work, our text encoder has exactly the same architecture as the visual encoder, i.e., we use the same ViT architecture (but with different parameters) for both the visual and textual encoder, i.e. ViT-B/16. (p. 3)

Multimodal encoder

We use a separate transformer to fuse the image and text hidden states. Specifically, we apply two learned linear projections over each hidden state vector in {hI } and {hT }, and concatenate them into a single list with an additional [CLS M] token added, as shown in Figure 2. This concatenated list is fed into the multimodal encoder transformer (also based on the ViT architecture), allowing cross-attention between the projected unimodal image and text representations and fusing the two modalities. The output from the multimodal encoder is a list of hidden states {hM}, each corresponding to a unimodal vector from {hI } or {hT } (and a vector hCLS,M for [CLS M]). (p. 3)

Multimodal pretraining objectives

Global contrastive (GC) loss

Our image-text contrastive loss resembles that of CLIP [83]. This is accomplished by linearly projecting each hCLS,I and hCLS,T into an embedding space, followed by L2-normalization, dot-product, and a softmax loss scaled by temperature (p. 4)

In contrast, through experiments that can be found in the supplemental, we observe a noticeable performance gain by performing full backpropagation across GPUs compared to only doing backpropagation locally. We call our loss “global contrastive” LGC to distinguish it from “local contrastive” approaches. (p. 4)

Masked multimodal modeling (MMM)

Specifically, given an image and text input, we first tokenize the input image patches using a pretrained dVAE tokenizer [89], which maps each image patch into an index in a visual codebook similar to a word dictionary (we use the same dVAE tokenizer as in [5]). Then, we replace a subset of image patches based on rectangular block image regions following BEiT [5] and 15% of text tokens following BERT [28] with a special [MASK] token. Then, from the multimodal encoder’s output {hM}, we apply a multilayer perceptron to predict the visual codebook index of the masked image patches, or the word vocabulary index of the masked text tokens. (p. 4)

Image-text matching (ITM)

Finally, we add an image-text matching loss LITM following prior vision-and-language pretraining literature [16, 70, 102]. During pretraining, we feed a batch of samples including both matched and unmatched image-text pairs. Then, on top of hCLS,M from the multimodal encoder, we apply a classifier to decide if an input image and text match each other. (p. 4)

Unimodal pretraining objectives

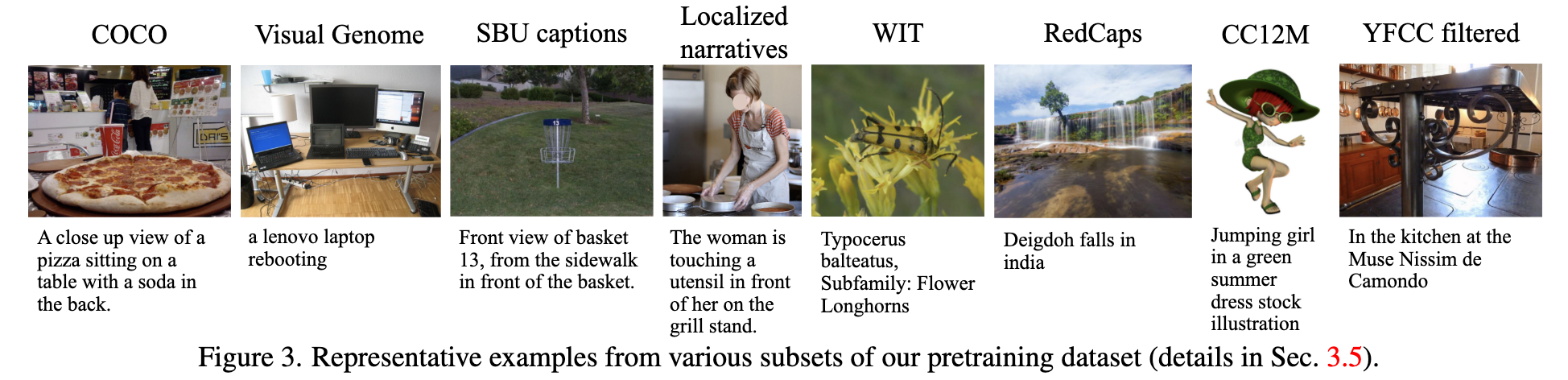

In this work, we introduce knowledge and information from these unimodal datasets through 1) pretraining the image encoder and text encoder on unimodal datasets; 2) pretraining the entire FLAVA model jointly on both unimodal and multimodal datasets; or 3) a combination of both by starting from pretrained encoders and then jointly training. When applied to stand-alone image or text data, we adopt masked image modeling (MIM) and masked language modeling (MLM) losses over the image and text encoders respectively, as described in what follows. (p. 4)

Encoder initialization from unimodal pretraining

We first pretrain the text encoder with the MLM objective on the unimodal text dataset. We experiment with different ways for pretraining the image encoder: we pretrain the image encoder on unpaired image datasets with either MIM or the DINO objective [13], before joint training on both unimodal and multimodal datasets. (p. 4)

Then, we initialize the whole FLAVA model with the two respective unimodallypretrained encoders, or when we train from scratch, we initialize randomly. We always initialize the multimodal encoder randomly for pretraining. (p. 5)

Joint unimodal and multimodal training

After unimodal pretraining of the image and text encoders, we continue training the entire FLAVA model jointly on the three types of datasets with round-robin sampling. In each training iteration, we choose one of the datasets according to a sampling ratio that we determine empirically (see supplemental) and obtain a batch of samples. Then, depending on the dataset type, we apply unimodal MIM on image data, unimodal MLM on text data, or the multimodal losses (contrastive, MMM, and ITM) in Sec. 3.2 on image-text pairs. (p. 5)

Implementation details

A large batch size, a large weight decay, and a long warm-up are all important for preventing divergence with a large learning rate (we use 8,192 batch size, 1e-3 learning rate, 0.1 weight decay, and 10,000 iteration warm-up in our pretraining tasks together with the AdamW optimizer [55, 69]). In addition, the ViT transformer architecture (which applies layer norm [3] before the multi-head attention rather than after [115]) provides more robust learning for the text encoder under large learning rate than the BERT [28] transformer architecture. FLAVA is implemented using the open-source MMF [94] and fairseq [78] libraries. We use Fully-Sharded Data Parallel (FSDP) [86,87] and train in full FP16 precision except the layer norm [3] to reduce GPU memory consumption. (p. 5)

Experiment

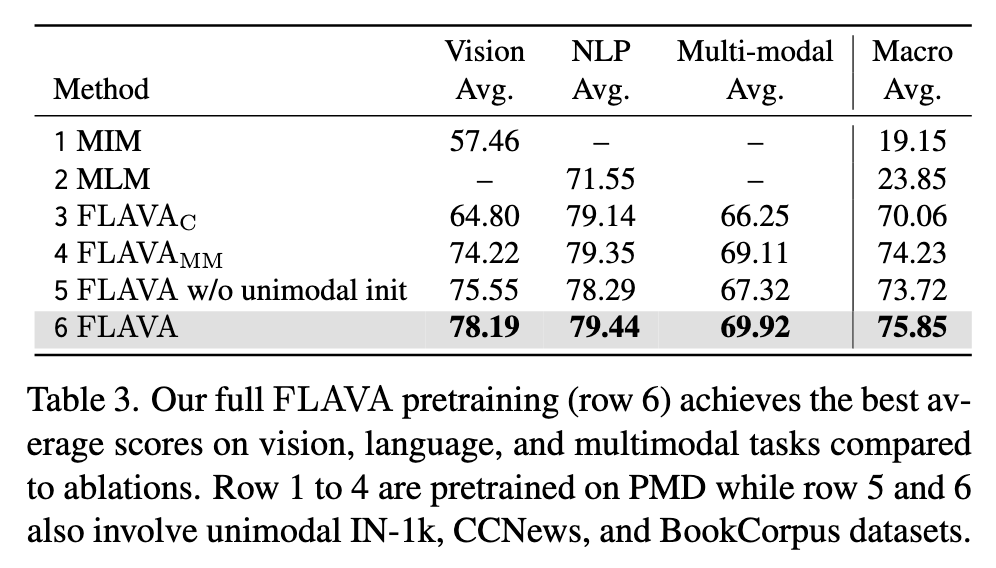

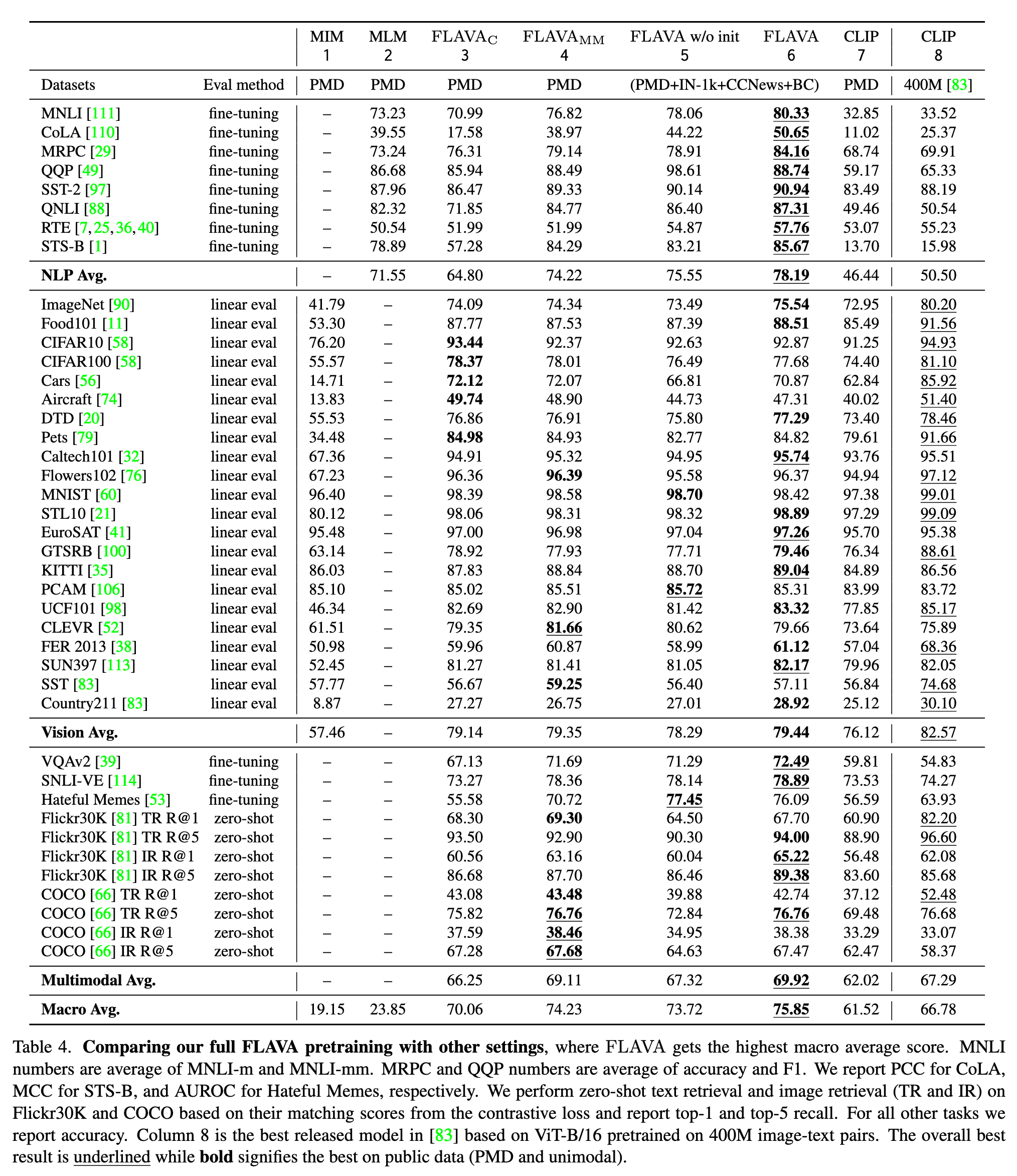

Ablation

Global vs. local contrastive losses.

In our FLAVA model, we apply a global contrastive loss, where the image and text features are gathered across GPUs and the loss is backpropagated through the gathering operation to all GPUs. This is in contrast with the implementation in [48], where the loss is only back-propagated to local features from the same GPU. It can be seen from Table C.1 (columns 3 vs 4) that the global contrastive loss (column 4) leads to a noticeable gain in the average vision and NLP performance compared to its local contrastive counterpart and also provides a slight boost in multimodal performance. (p. 15)