Scalable Adaptive Computation for Iterative Generation

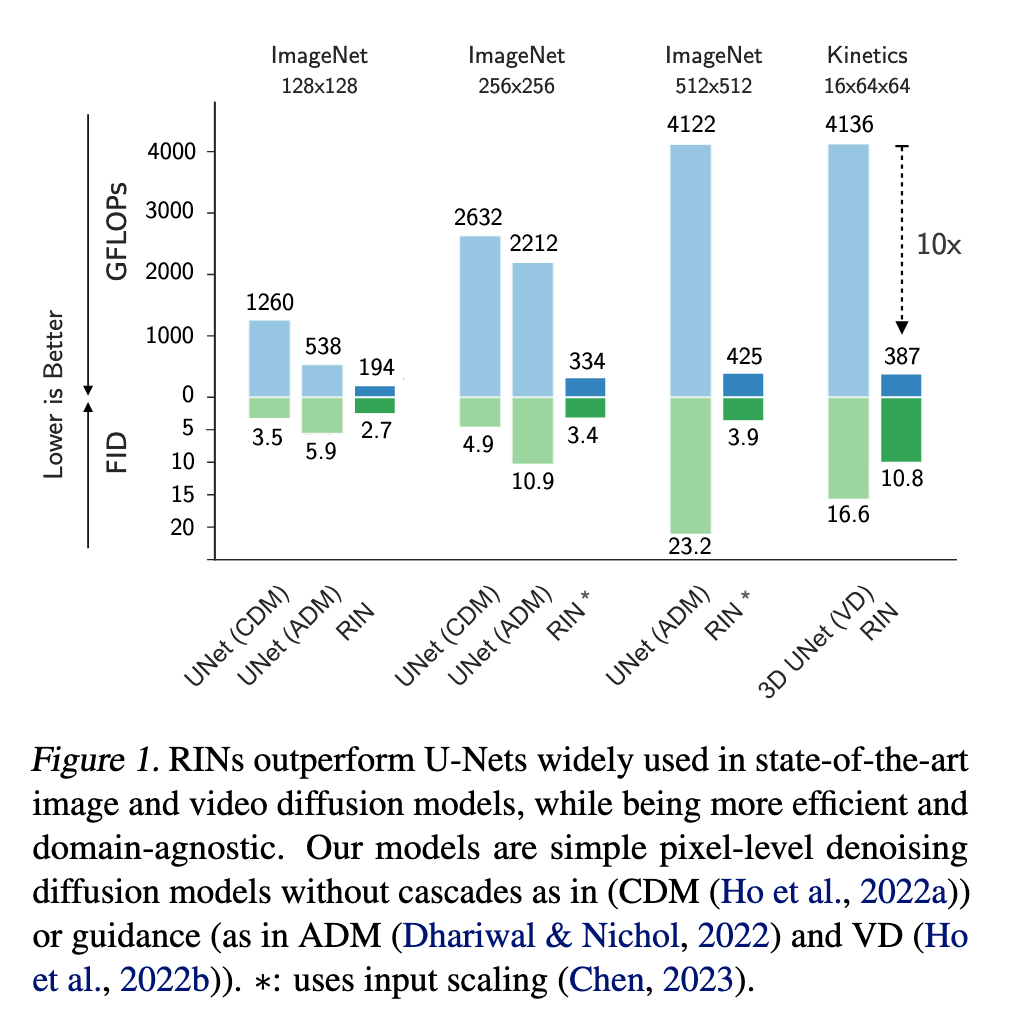

[text2video diffusion unet deep-learning text2image recurrent-neural-network This is my reading note on Scalable Adaptive Computation for Iterative Generation The major innovation here is to map the input token to latents, which is shorter. The latents could be initialized from previous iterations (of diffusion process). As a result, the new method could achieve similar visual fidelity as regular diffusion method but with 1/10 of cost.

Introduction

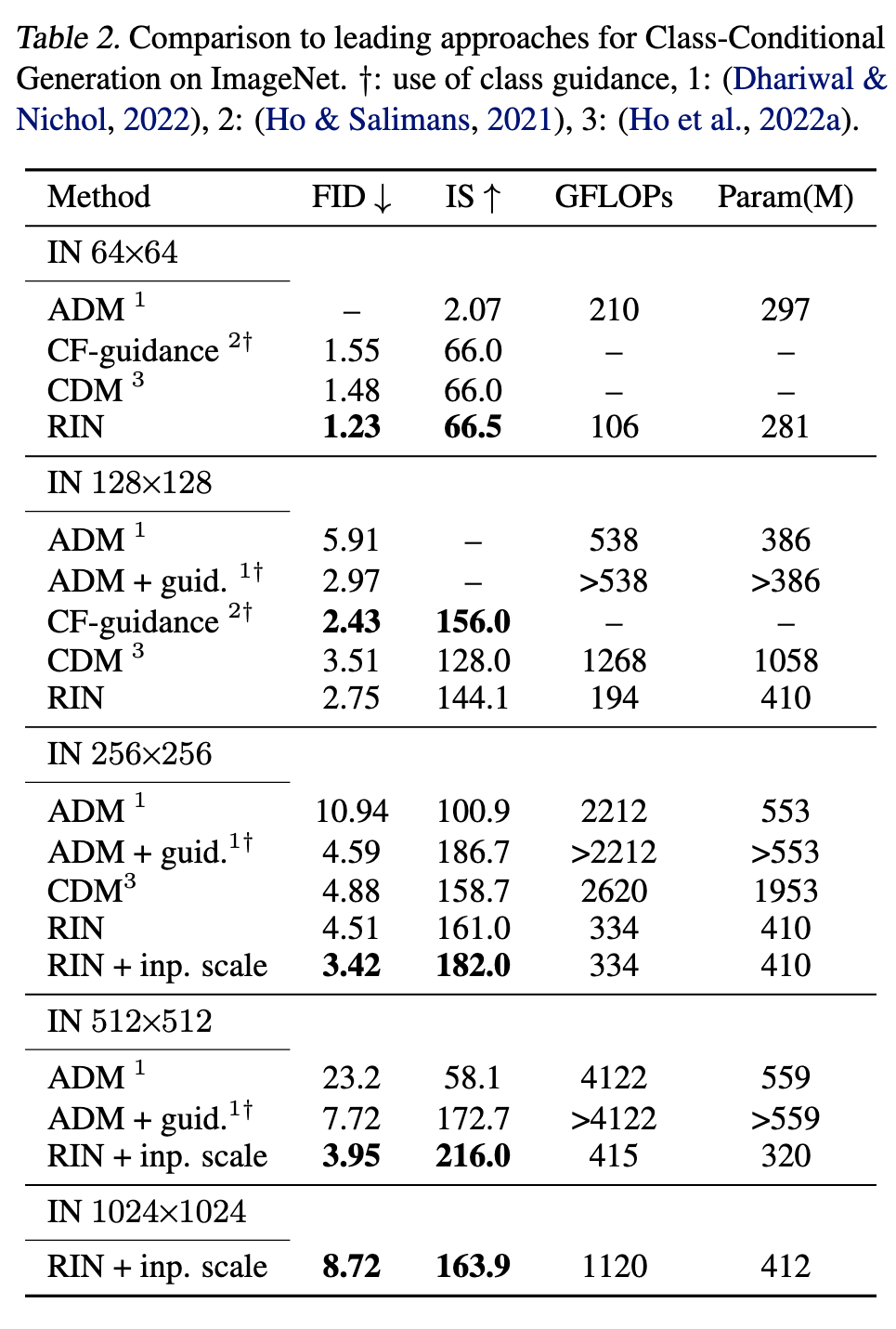

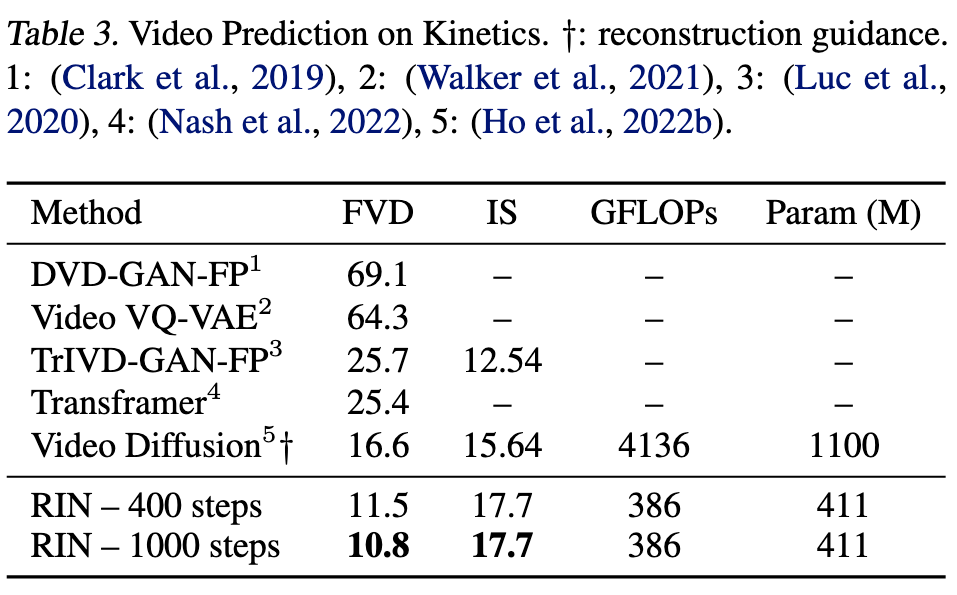

We propose the Recurrent Interface Networks (RINs), an attention-based architecture that decouples its core computation from the dimensionality of the data, enabling adaptive computation for more scalable generation of high-dimensional data. RINs focus the bulk of computation (i.e. global self-attention) on a set of latent tokens, using cross-attention to read and write (i.e. route) information between la- tent and data tokens. Stacking RIN blocks allows bottom-up (data to latent) and top-down (latent to data) feedback, leading to deeper and more expressive routing. While this routing introduces challenges, this is less problematic in recurrent computation settings where the task (and routing problem) changes gradually, such as iterative generation with diffusion models. We show how to leverage recurrence by conditioning the latent to- kens at each forward pass of the reverse diffusion process with those from prior computation, i.e. la- tent self-conditioning. RINs yield state-of-the-art pixel diffusion models for image and video generation, scaling to 1024×1024 images without cascades or guidance, while being domain-agnostic and up to 10× more efficient than 2D and 3D U-Nets. (p. 1)

Information in natural data is often distributed unevenly, or exhibits redundancy, so it is important to ask how to allocate computation in an adap- tive manner to improve scalability. While prior work has explored more dynamic and input-decoupled computation, e.g., networks with auxiliary memory (Dai et al., 2019; Rae et al., 2019) and global units (Zaheer et al., 2020; Burtsev et al., 2020; Jaegle et al., 2021b;a), general architectures that leverage adaptive computation to effectively scale to tasks with large input and output spaces remain elusive (p. 1)

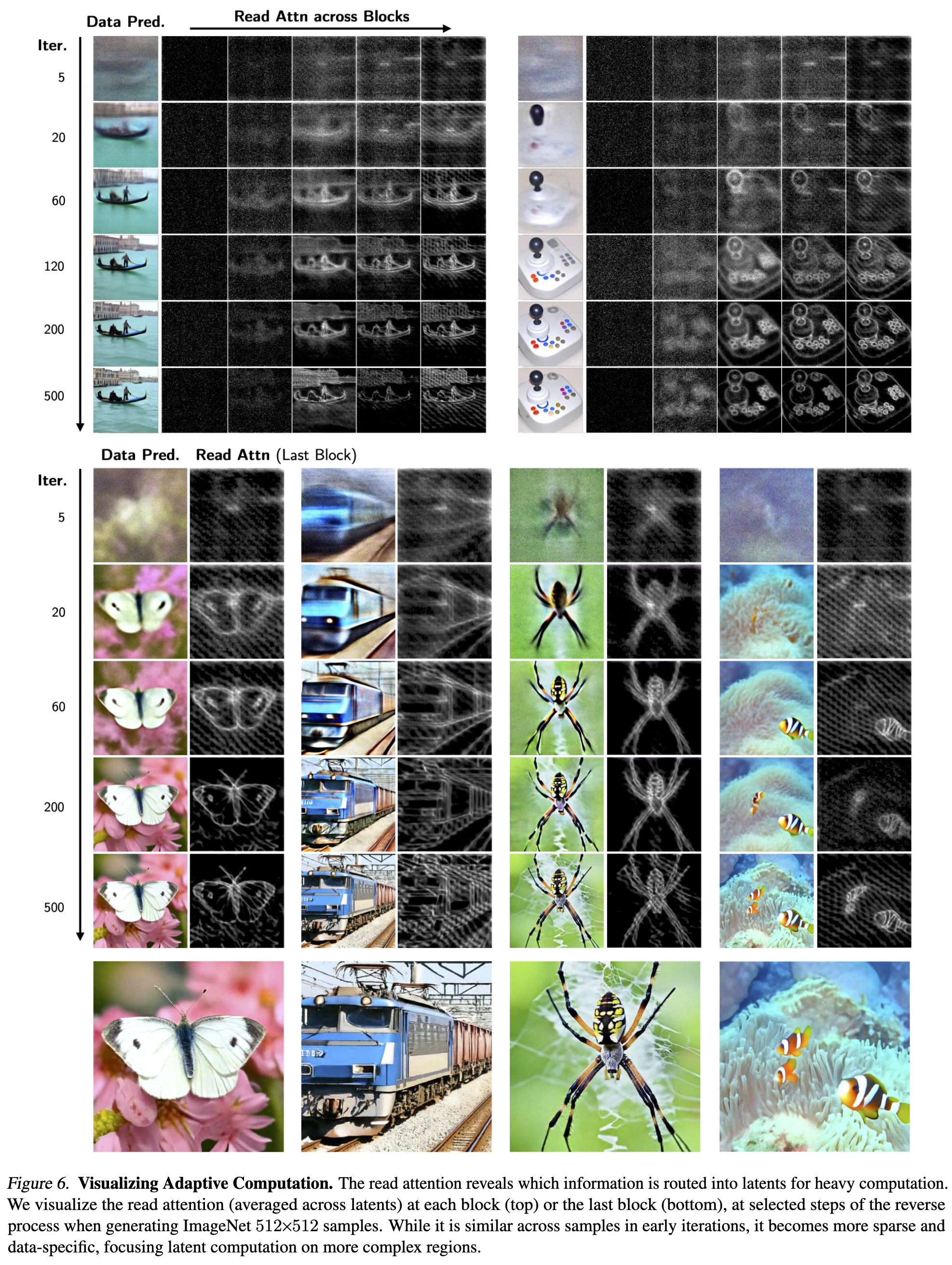

When generating an image with a simple background, an adaptive architecture should ideally be able to allocate computation to regions with complex objects and textures, rather than regions with little or no structure (e.g., the sky). When generating video, one should exploit tempo- ral redundancy, allocating less computation to static regions. While such non-uniform computation becomes more crucial in higher-dimensional data, achieving it efficiently is challenging, especially with modern hardware that favours fixed (p. 1) computation graphs and dense matrix multiplication.

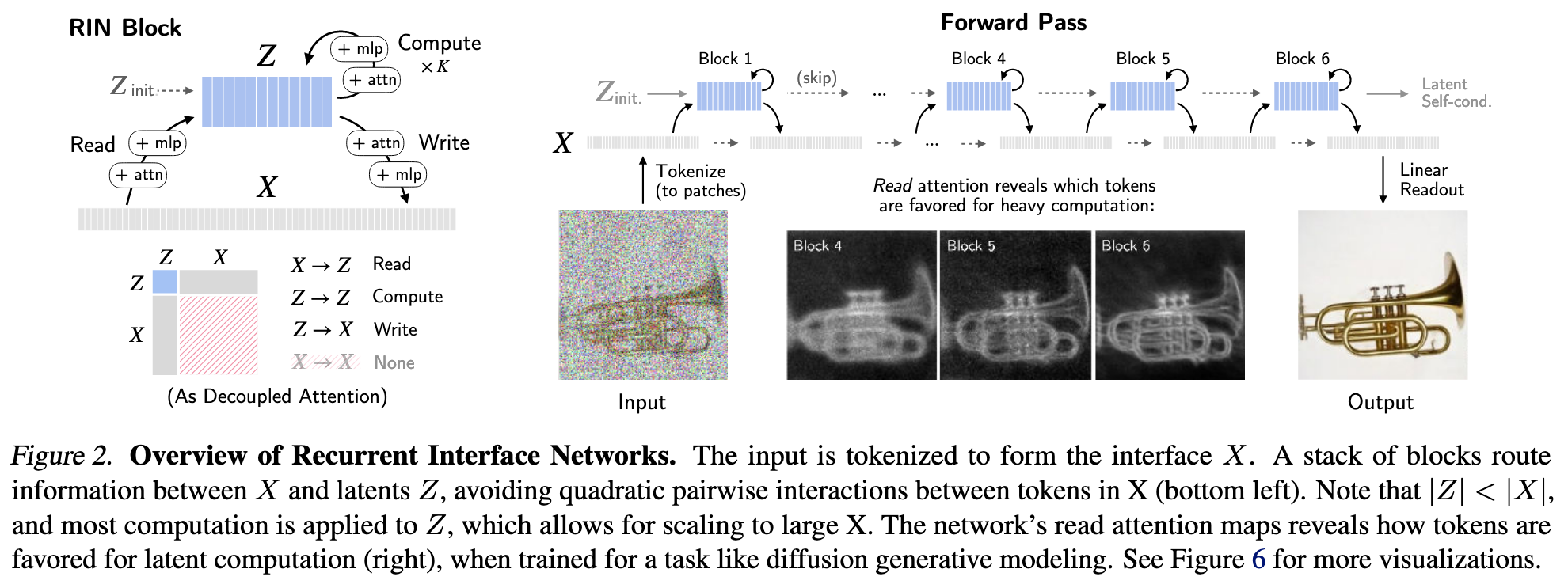

To address this challenge, we propose an architecture, dubbed Recurrent Interface Networks (RINs). In RINs (Fig. 2), hidden units are partitioned into the interface X and latents Z. Interface units are locally connected to the in- put and grow linearly with input size. In contrast, latents are decoupled from the input space, forming a more compact representation on which the bulk of computation operates.

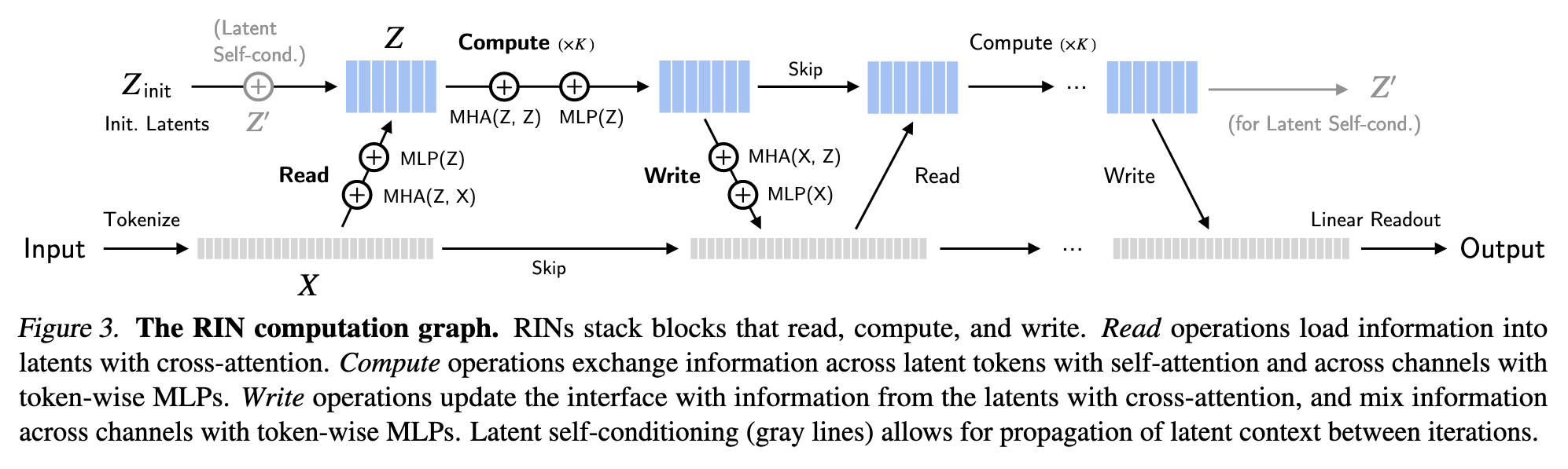

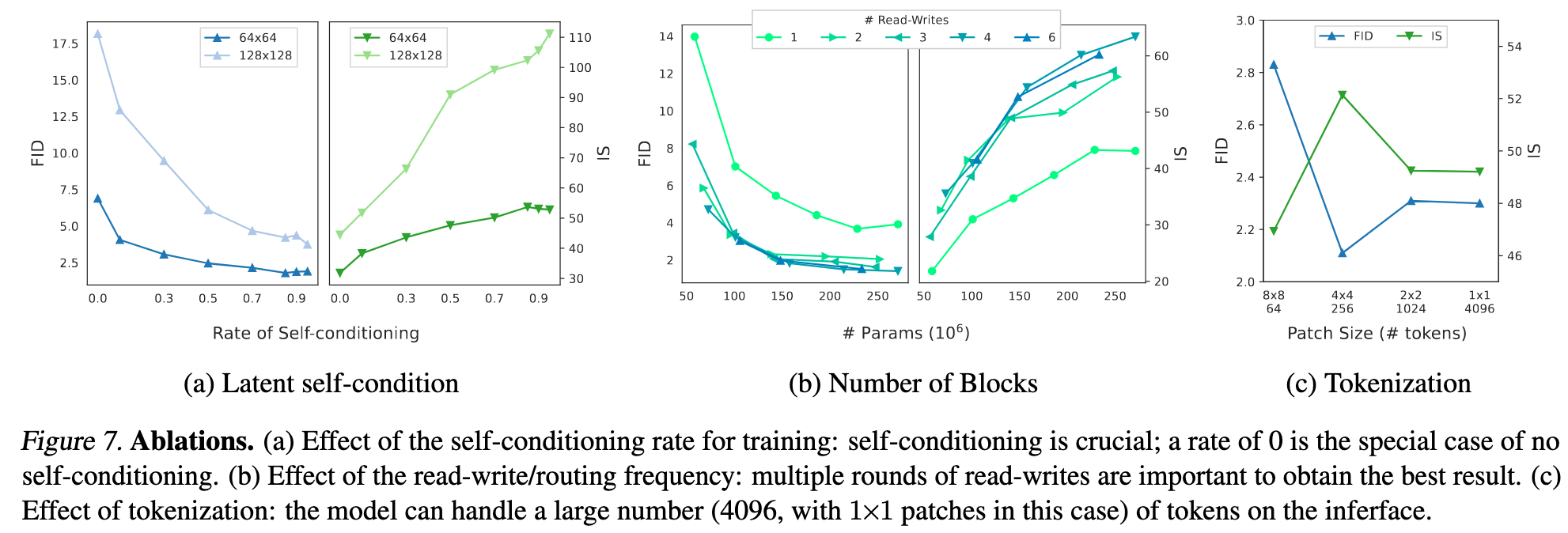

The forward pass proceeds as a stack of blocks that read, compute, and write: in each block, information is routed from interface tokens (with cross-attention) into the latents for high-capacity global processing (with self-attention), and updates are written back to interface tokens (with cross- attention). Alternating computation between latents and interface allows for processing at local and global levels, accumulating context for better routing. As such, RINs allocate computation more dynamically than uniform mod- els, scaling better when information is unevenly distributed across the input and output, as is common in natural data.

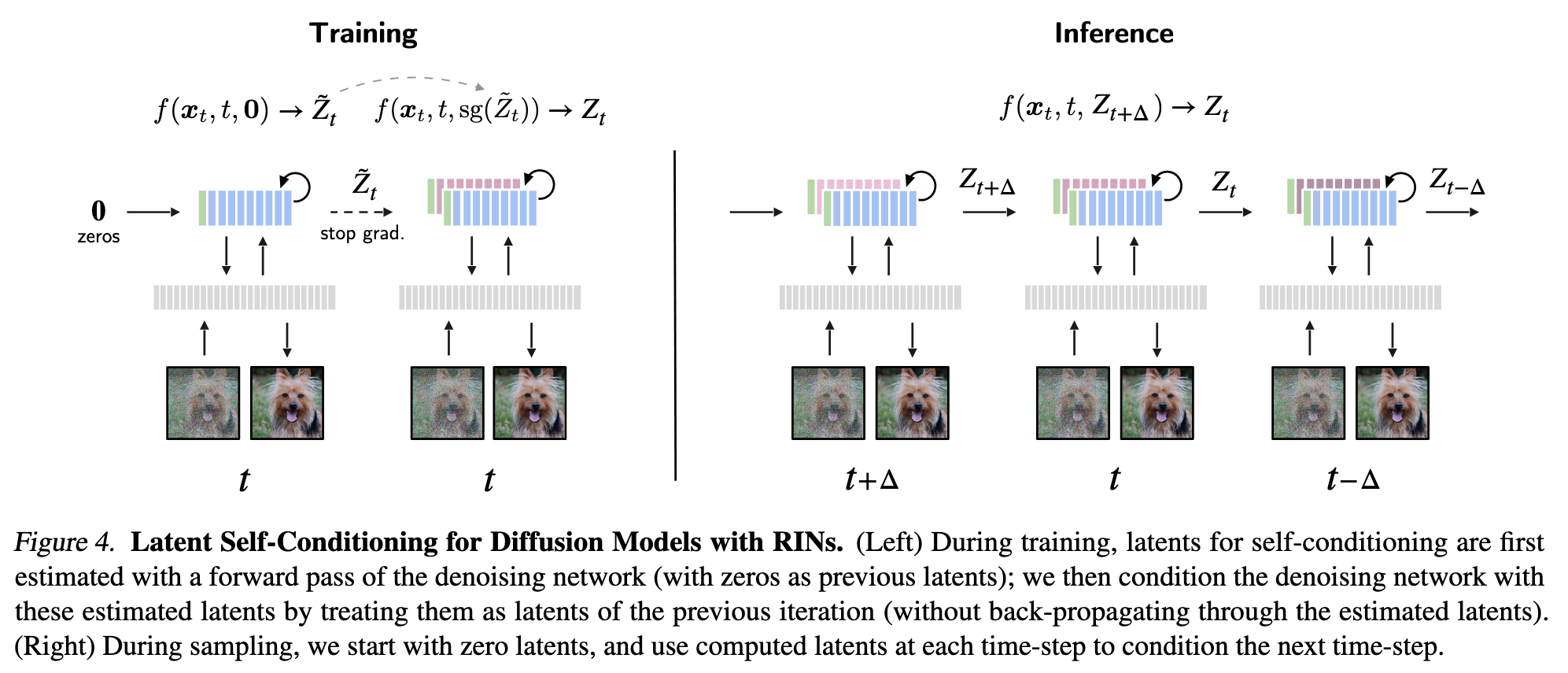

This decoupling introduces additional challenges, which can overshadow benefits if the latents are initialized with- out context in each forward pass, leading to shallow and less expressive routing. We show this can be mitigated in scenarios involving recurrent computation, where the task and routing problem change gradually such that persistent context can be leveraged across iterations to in effect form a deeper network. In particular, we consider iterative generation of images and video with denoising diffusion models (Sohl-Dickstein et al., 2015; Ho et al., 2020; Song et al., 2020; 2021). To leverage recurrence, we propose latent self-conditioning as a “warm-start” mechanism for latents: instead of reinitializing latents at each forward pass, we use latents from previous iterations as additional context, like a recurrent network but without requiring back propagation through time. (p. 2)

Proposed Method

Compared to convolutional nets such as U-Nets (Ron- neberger et al., 2015), RINs do not rely on fixed down- sampling or upsampling for global computation. Compared to Transformers (Vaswani et al., 2017), RINs operate on sets of tokens with positional encoding for similar flexibility across input domains, but avoid pairwise attention across tokens to reduce compute and memory requirements per token. Compared to other decoupled architectures such as PerceiverIO (Jaegle et al., 2021b;a), alternating computation between interface and latents enables more expressive routing without a prohibitively large set of latents.

While RINs are versatile, their advantages are more pronounced in recurrent settings, where inputs may change gradually over time such that it is possible to propagate persistent context to further prime the routing of informa- tion. Therefore, here we focus on the application of RINs to iterative generation with diffusion models. (p. 3)

Interface Initialization. The interface is initialized from an input x, such as an image $x_{image}\in R^{h×w×3}$, or video $x_{video} \in R^{h×w×l×3}$ by tokenizing x into a set of n vectors $X \in R^{n×d}$. For example, we use a linear patch embedding similar to (Dosovitskiy et al., 2020) to convert an image into a set of patch tokens; for video, we use 3-D patches. To indicate their location, patch embeddings are summed with (learnable) positional encodings. Beyond tokenization, the model is domain-agnostic, as X is simply a set of vectors. (p. 3)

Elements of Recurrent Interface Networks

Latent Initialization. The latents $Z \in R^{m×d′}$ are (for now) initialized as learned embeddings, independent of the input. Conditioning variables, such as class labels and time step t of diffusion models, are mapped to embeddings; in our experiments, we simply concatenate them to the set of latents, since they only account for two tokens. (p. 3)

MLP denotes a multi-layer perceptron, and MHA(Q, K) denotes multi-head attention with queries Q, and keys and values K.1 (p. 4)

From the perspective of information exchange among hidden units, MHA propagates information across vectors (i.e. between latents, or between latents and interface), while the MLP (applied vector-wise, with shared weights) mixes information across their channels. (p. 4)

Note, $m\ll n$, thus computation on latents could be more efficient.

Latent Self-Conditioning

Warm-starting Latents. With this in mind, we propose to “warm-start” the latents using latents computed at a previous step. The initial latents at current time step t are the sum of the learnable embeddings Zinit (independent of the input), and a transformation of previous latents computed in the previous iteration t′: \(Z_t=Z_{init}+\mbox{LayerNorm}(Z_{t'}+MLP(Z_{t'}))\) where LayerNorm is initialized with zero scaling and bias, so that Z_t = Z_init early in training. (p. 4)

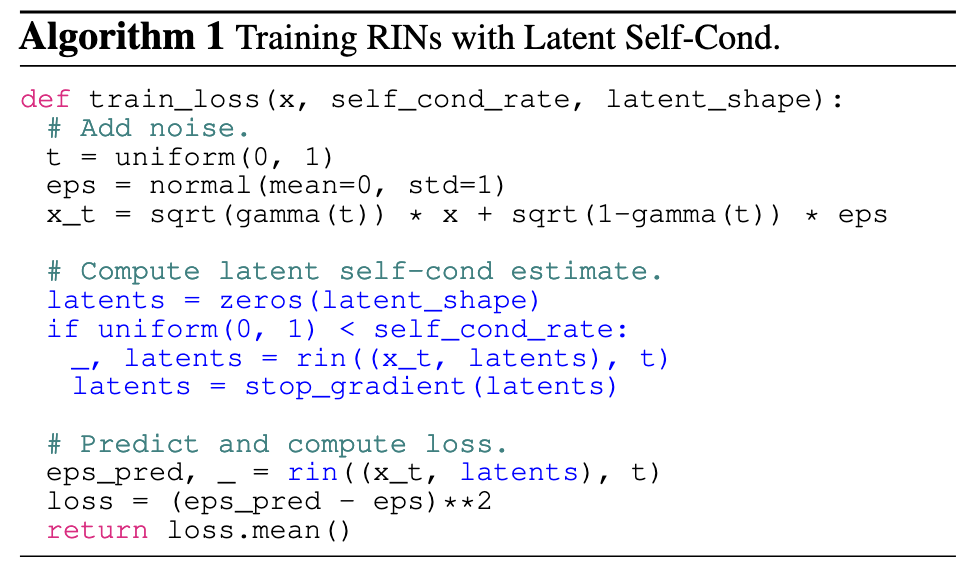

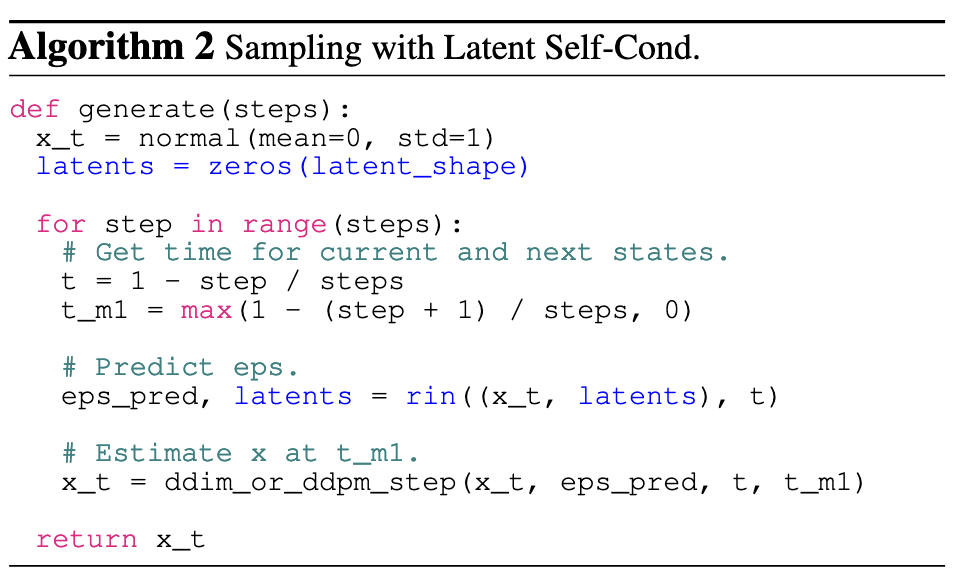

Concretely, consider the conditional denoising network f(xt, t, Zt′ ) that takes as input xt and t, as well as context latents Zt′ . During training, with some probability, we use f(xt, t, 0) to directly compute the prediction ˜ϵt. Otherwise, (p. 4). we first apply f(xt, t, 0) to obtain latents Z˜ t as an estimate of Zt′ , and compute the prediction with f(xt, t,sg(Z˜ t)). Here, sg is the stop-gradient operation, used to avoid back- propagating through the latent estimates. At inference time, we directly use latents from previous time step t′ to initialize the latents at current time step t, i.e., f(xt, t, Zt′ ), in a recurrent fashion. (p. 5)

Experiment

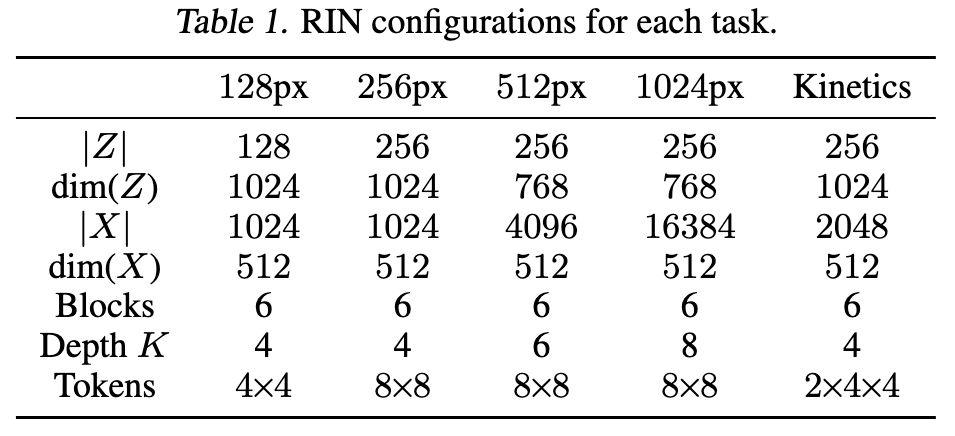

Tokenization and Readout. For image generation, we tokenize images by extracting non-overlapping patches fol- lowed by a linear projection. We use a patch size of 4 for 64×64 and 128×128 images, and 8 for larger images. To produce the output, we apply a linear projection to interface tokens and unfold each projected token to obtain predicted patches, which we reshape to form an image. For video, we tokenize and produce predictions in the same manner as images; for 16×64×64 inputs, we use 2×4×4 patches, resulting in 2048 tokens. (p. 5)

Ablation

Latent Self-conditioning. We study the effect of the rate ofA rate of 0 denotes the special case where no self-conditioning is used (for training nor inference), while a rate > 0 e.g. 0.9 means that self- conditioning is used for 90% of each batch of training tasks (and always used at inference). As demonstrated in Figure 7a, there is a clear correlation between self-conditioning rate and sample quality (i.e., FID/IS), validating the importance using latent self-conditioning to provide context for enhanced routing. We use 0.9 for the best results reported. (p. 8)

Latent Self-conditioning. We study the effect of the rate ofA rate of 0 denotes the special case where no self-conditioning is used (for training nor inference), while a rate > 0 e.g. 0.9 means that self- conditioning is used for 90% of each batch of training tasks (and always used at inference). As demonstrated in Figure 7a, there is a clear correlation between self-conditioning rate and sample quality (i.e., FID/IS), validating the importance using latent self-conditioning to provide context for enhanced routing. We use 0.9 for the best results reported. (p. 8)

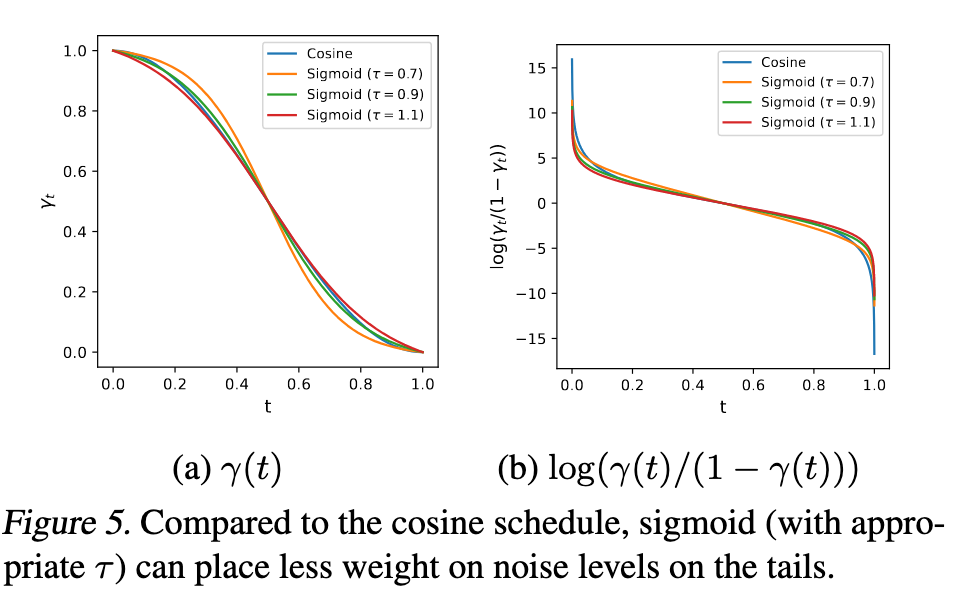

Effect of Noise Schedule. We find that the sigmoid schedule with an appropriate temperature is more stable training than the cosine schedule, particularly for larger images. For sampling, the noise schedule has less impact and the default cosine schedule can suffice (see Appendix Figure B.1). (p. 8)