Key-Locked Rank One Editing for Text-to-Image Personalization

[perfusion attention prompt2prompt diffusion paint-with-words personalize textual-inversion deep-learning dreambooth image2image This is my reading note on Key-Locked Rank One Editing for Text-to-Image Personalization. This paper proposes a personalized image generation method base on controlling attention module of the diffusion model. Especially key captures the layout of concept and value captures the identity of the new concept. A rank one update is applied to the attention weight to this purpose.

Introduction

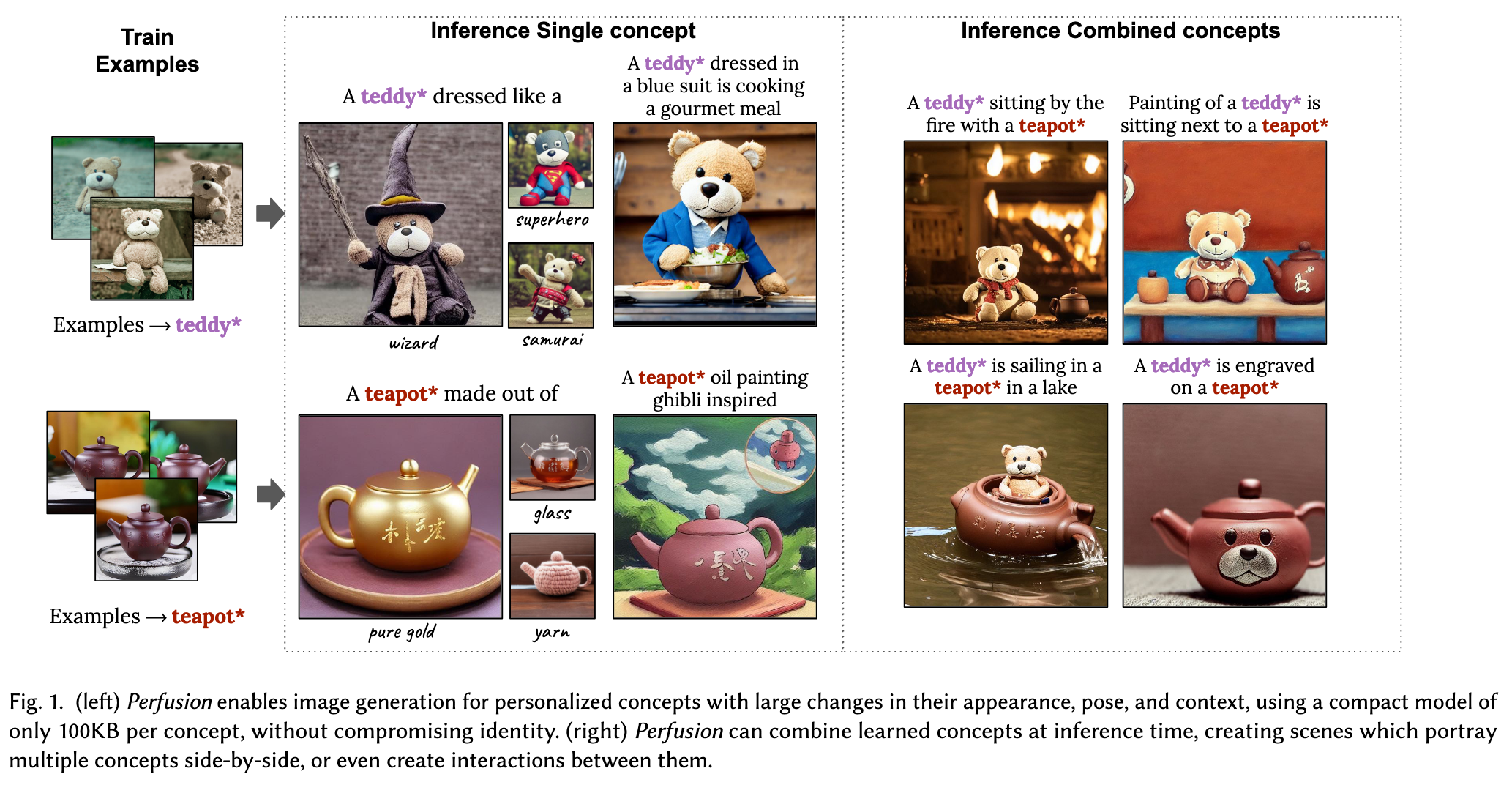

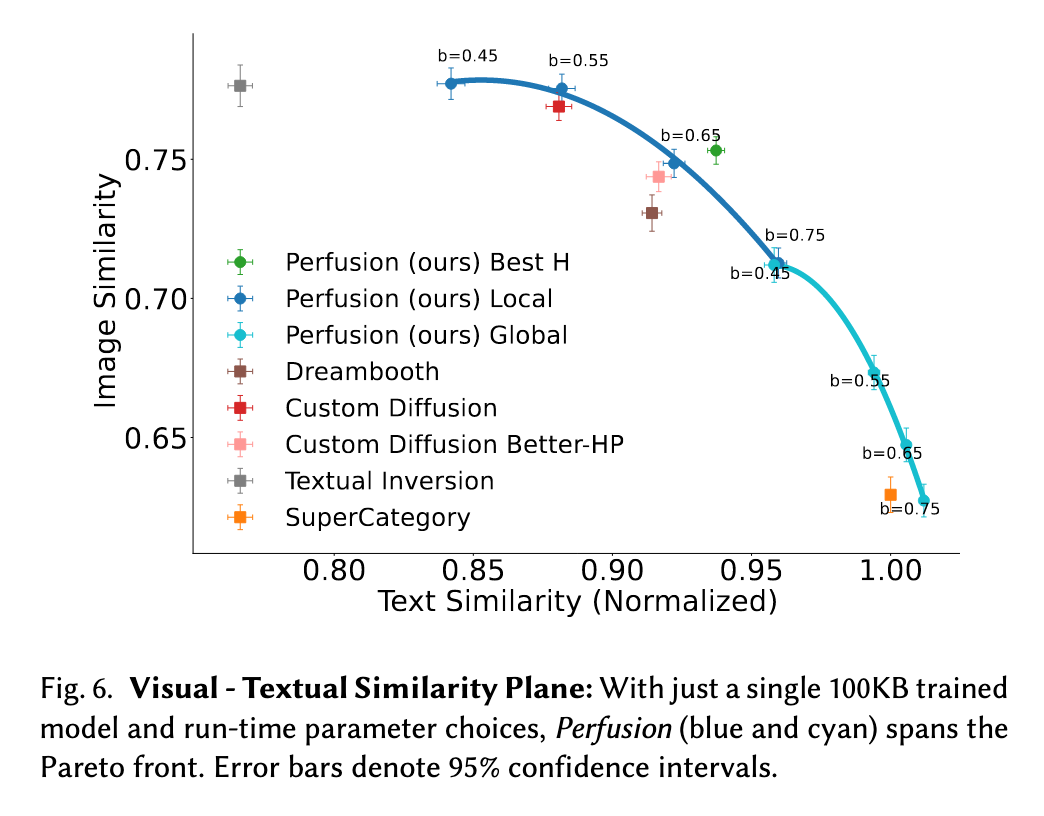

We present Perfusion, a T2I personalization method that addresses these challenges using dynamic rank-1 updates to the underlying T2I model. Perfusion avoids overfitting by introducing a new mechanism that “locks” new concepts’ cross-attention Keys to their superordinate category. Additionally, we develop a gated rank-1 approach that enables us to control the influence of a learned concept during inference time and to combine multiple concepts. This allows runtime-efficient balancing of visual-fidelity and textual-alignment with a single 100KB trained model, which is five orders of magnitude smaller than the current state of the art. (p. 1)

Current methods for personalization take one of two main approaches.

- They either represent a concept through a word embedding at the input of the text encoder [Cohen et al. 2022; Gal et al. 2022]

- or fine-tune the full weights of the diffusion-based denoiser module [Ruiz et al. 2022].

Unfortunately, these approaches are prone to different types of overfitting. As we show below,

- word embedding methods struggle to generalize to unseen text prompts. This is reflected in their textual-alignment scores which tend to be low.

- Fine-tuning methods can better generalize to new text prompts, but they still lack expressivity, as reflected in their textual and visual alignment scores which tend to be lower than our method.

- Moreover, tuning methods typically demand significant storage space, often in the range of hundreds of megabytes or even gigabytes.

- Lastly, both approaches struggle to combine concepts that were trained individually, such as a teddy* and a teapot* (Fig. 1), in a single prompt. (p. 2)

Most relevant to our work are the paint-with-words (PWW) approach introduced by Balaji et al. [2022], and prompt-toprompt (P2P) [Hertz et al. 2022]. PWW biases the attention map toward a predefined mask during inference time. P2P edits a given generated image, by regenerating it with a new prompt while injecting the attention maps of the original image along the diffusion process. In contrast to these methods, we do not edit given images but learn to represent a personalized concept that can be invoked in new prompts. Additionally, we do not override the attention map, but constrain the cross-attention Keys of the new concept. These are a contributing factor to the attention map, but they still allow for concept-specific modifications through the Query features. (p. 3)

Proposed Methods

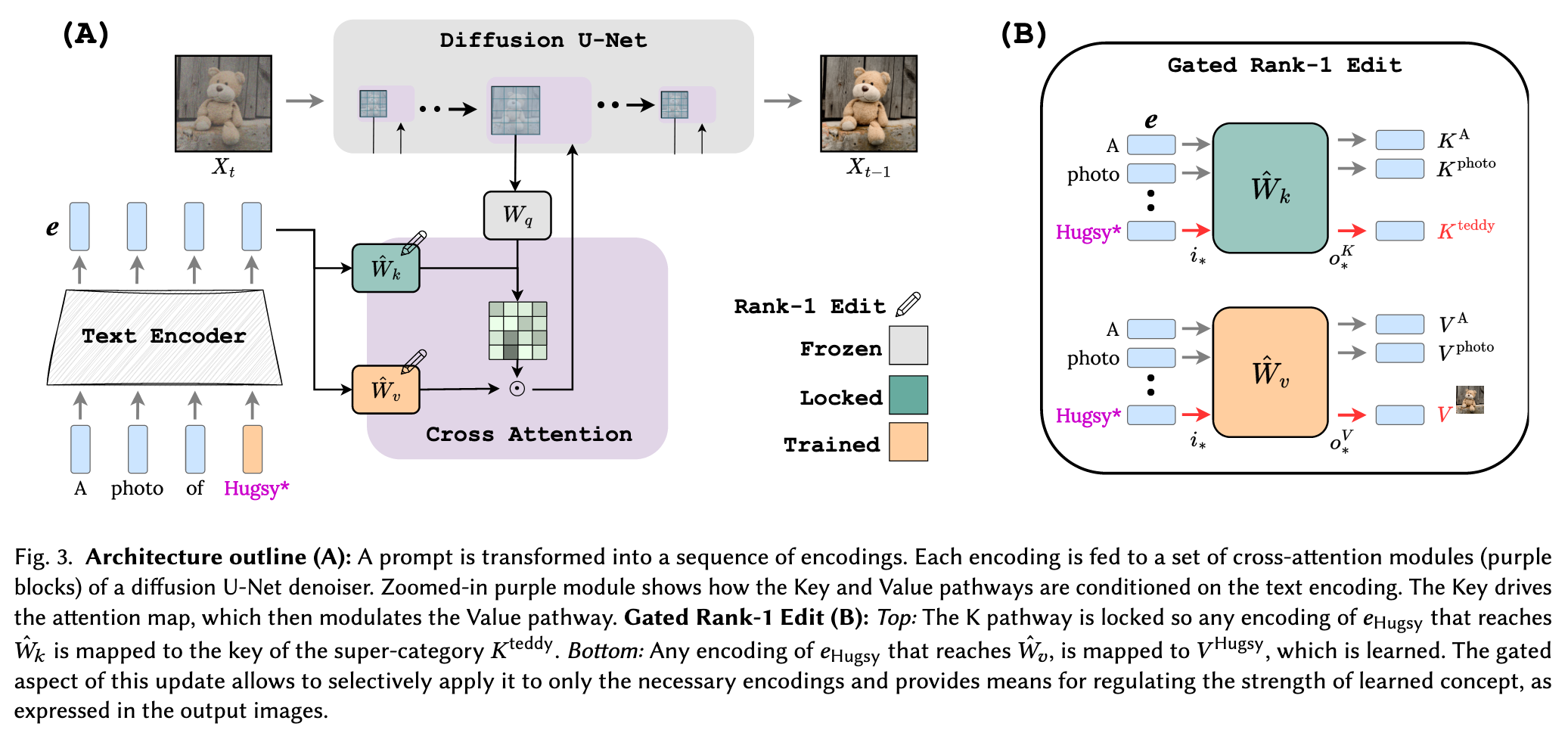

The Keys (K) are a “Where” pathway, which controls the layout of the attention maps, and through them the compositional structure of the generated image. The Values (V) are a “What” pathway, which controls the visual appearance of the image components.

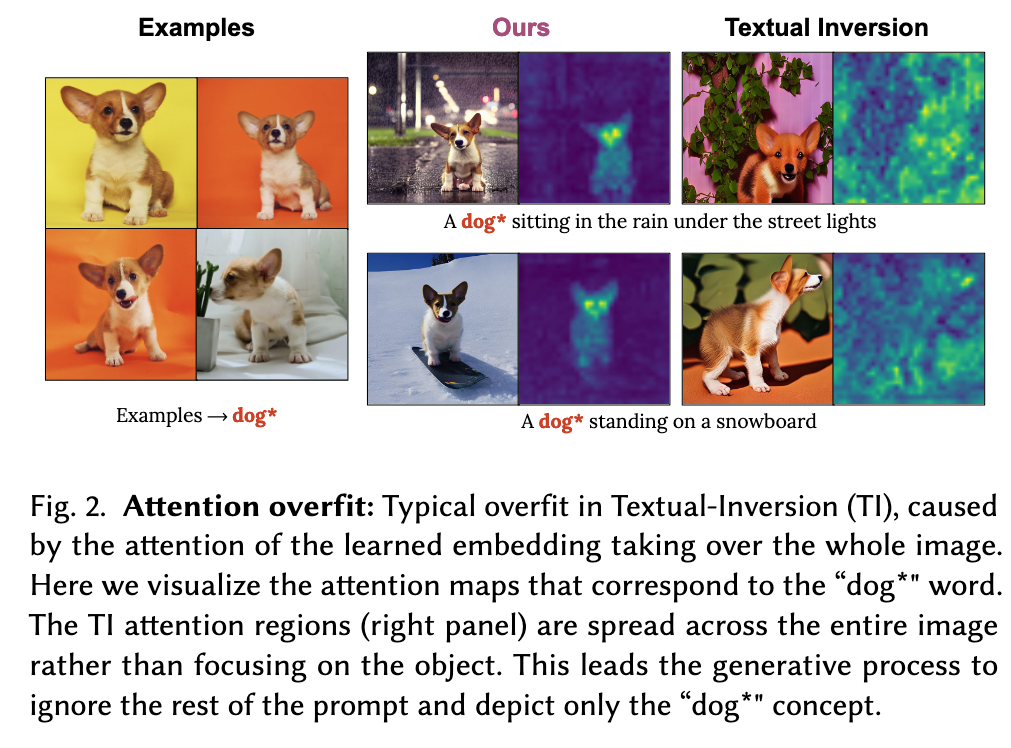

Our main insight is that existing techniques fail when they overfit the Where pathway (Figures 2, 11), causing the attention on the novel words to leak beyond the visual scope of the concept itself. To address this shortcoming, we propose a novel “Key-Locking” mechanism, where the keys of a concept are fixated on the keys of the concept’s super-category. For example, the keys that represent a specific teddybear may be key-locked to the super-category of a teddy instead. Intuitively, this allows the new concept to inherit the super-category’s qualities and creative power (Figure 1). Personalization is then handled through the What (V) pathway, where we treat the Value projections as an extended latent-space and concurrently optimize them along with the input word embedding (p. 2)

Finally, we describe how these components can be incorporated directly into the T2I model through the use of a gated rank-1 update to the weights of the K and V projection matrices. The gated aspect of this update allows us to combine multiple concepts at inference time by selectively applying the rank-1 update to only the necessary encodings. Moreover, the same gating mechanism provides a means for regulating the strength of learned concept, as expressed in the output images. This allows runtime efficient, inference-time trade-off of visual-fidelity with textual-alignment, without requiring specialized models for every new operating point. Empirically, Perfusion not only leads to more accurate personalization at a fraction of the model size, but it also enables the use of more complex prompts and the combination of individually-learned concepts at inference time. (p. 2)

Two conflicting goals and one Naïve Solution

Personalized T2I aims to achieve two goals:

- Avoid overfitting to the example images, so the personalized concept can be generated in various poses, appearances, or context; and

- Preserve the identity of the personalized concept in the generated image, despite being portrayed in a different pose appearance or context. There is a natural trade-off between these two goals. (p. 3)

Avoid overfitting. In preliminary experimentation, we noticed that when learning personalized concepts from a limited number of examples, the model weights of the Where pathway (𝑾𝐾) are prone to overfit to the image layout seen in these examples. Figure 2 illustrates this problem showing that the personalized examples may ‘dominate’ the entire attention map, and prevent other words from affecting the synthesized image. We thus aim to prevent this attention-based overfitting by restricting the Where pathway.

Preserving Identity. In Image2StyleGAN, Abdal et al. [2019] proposed a hierarchical latent-representation to capture identities more effectively. There, instead of predicting a single latent code at the generator’s input space, they predicted a different code for each resolution in the synthesis process. We propose the What (V) pathway activations as a similar latent space, given their compact nature and the multi-resolution structure of the underlying U-Net denoiser (p. 4)

A Naïve Solution. Whenever the encoding contains the target concept, ensure that its cross-attention keys match those of its super-category, which we call Key Locking. Additionally, we want the cross-attention values to represent the concept in the multi-resolution latent space. (p. 4)

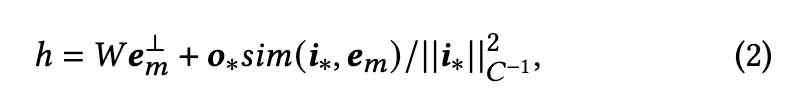

One way to implement this idea would be a simple vector replacement simply swapping out the keys and values assigned to the encoding at the personalized concept’s index. However, this fails to account for the cross-word information sharing in the text encoder. By the time the encoding reaches the denoiser’s cross-attention layers, its features are already influenced by the features of other words in the text, and in turn, influence them as well. We (p. 4)

A natural solution is then to edit the weights of the cross-attention layers, 𝑾𝑉 and 𝑾𝐾 using ROME. Specifically, when given a targetinput 𝑖Hugsy we enforce the 𝐾 activation to emit a specific targetoutput 𝑜𝐾 Hugsy = 𝐾teddy. Similarly, given a target-input 𝑖Hugsy, we enforce the 𝑉 activation to emit a learned output 𝑜𝑉 Hugsy = 𝑉 Hugsy (p. 4)

- Challenge 1: Training with ROME leads to a mismatch between training and inference. (p. 4)

- Challenge 2: A similar effect also prevents us from combining more than one learned concept, as their effects on the projections are not well-disentangled. Moreover, these new concepts are associated with multiple target-inputs 𝒊∗, which may themselves be inherently entangled (e.g. if the concepts share related semantics). Together, these lead to the creation of visual artifacts when attempting to combine concepts at inference-time.

To address these challenges we propose to align the training and inference steps of ROME, and introduce a new gating mechanism. Both components are described below. (p. 5)

Gated Rank-1 Model Editing for Personalized T2I

we propose to unify the second and third steps of ROME. As such, the target-output optimization and matrix update occur together during training. The network learns to account for any effects on other prompt-parts, avoiding the train-inference mismatch. (p. 5)

We found this approach introduced visual artifacts, even when the prompt only included a single learned concept. We hypothesize that this problem arises because the different 𝒊∗s of individually learned concepts may interfere with each other (p. 5)

To address this challenge, we use a gating mechanism to selectively allow or attenuate the influence of each concept on the layer output. (p. 5)

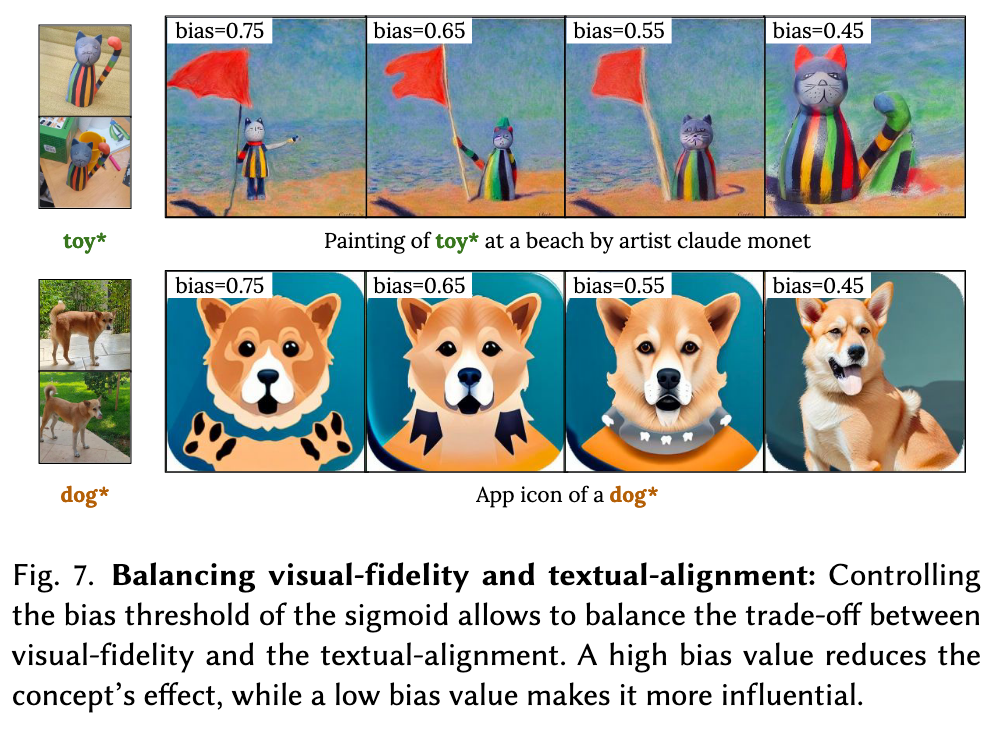

This non-linear gating mechanism therefore provides two important benefits: First, it allows us to better separate the influence of individually learned concepts during inference time. Second, even for a single concept, it allows for inference-time control over the influence of the concept. By adjusting the values of the sigmoid hyper-parameters, the bias and the temperature, we can trade visual fidelity with textual alignment and vice-versa. (p. 5)

Inference

Single concept: For inference with a single trained concept, we simply apply Eq. (3) to the forward pass of each edited cross-attention layer. We can control the strength of the depicted concept by changing the values of the sigmoid’s 𝜏 and 𝛽 at inference time. (p. 5)

Combining multiple concepts: To combine concepts that were trained in isolation, we extend equation Eq. (3) to include multiple concepts (p. 5)

Global Key-Locking: Key-Locking ensures that a concept’s Key is correctly aligned with its superconcept. However, it does not ensure that the text-encoder handles the concept in the same way it would have handled the superconcept and its correlations to the other words in the encoding. We also investigate an inference time method to align Key-locked concepts to an entire prompt. We refer to this variant as global key-locking, and to our vanilla mechanism as local key locking (p. 5)

Experiment

Ablation Study

In Figure 9 we study in greater depth the properties of Perfusion by an ablation study. We show the trade-off between visual and textual similarity for the following conditions.

- 1-shot: We compare between training our method with all the training examples (average of 6.5 image for each concept), to training with just a single example for each concept. We observe that training with just a single example introduces slight overfitting.

- Key-locking: We compare between our method with keylocking to our method with trained key projection layers. It is evident that key-locking shifts the Pareto curve to the right meaning less overfit. This result confirms our hypothesis that locking the key projection layers leads to better textualalignment and enables complex deformations of the learned concept.

- Zero-Shot Masking Loss: We compare the effects of training with and without a zero-shot mask. We notice that using zero-shot mask tends to improve the textual similarity, which mean it helps reduce the overfitting.

- Sigmoid Train Bias: We compare between different values of the Sigmoid biases used during training time. We notice that using a higher bias results in better Pareto front.

- Sigmoid Inference Temperature We compare between different values of the Sigmoid temperature used during inference time. We notice that using inference-time Sigmoid temperature that is higher than the train-time Sigmoid temperature results a better pareto front. Generally temperature of 0.15 tends to work better. (p. 9)

Different Lock Types

We find that global locking allows to generate rich scenes, portray better the nuances of the object attributes or activities, and in general allow more visual variability of the concept, compared to local key locking and trained-K (p. 11)

Balancing visual-fidelity and textual-alignment

Figure 7 provides qualitative examples for balancing the visual-fidelity versus the textual-alignment, by adjusting the sigmoid bias threshold. Higher bias values reduce the impact of the concept, while lower values give it more prominence in the generated image. This is because the concept energy is spread across multiple encodings in the text encoder, not just the one corresponding to the concept word. Lowering the bias increases its influence on all relevant encodings. (p. 11)