360 Reconstruction From a Single Image Using Space Carved Outpainting

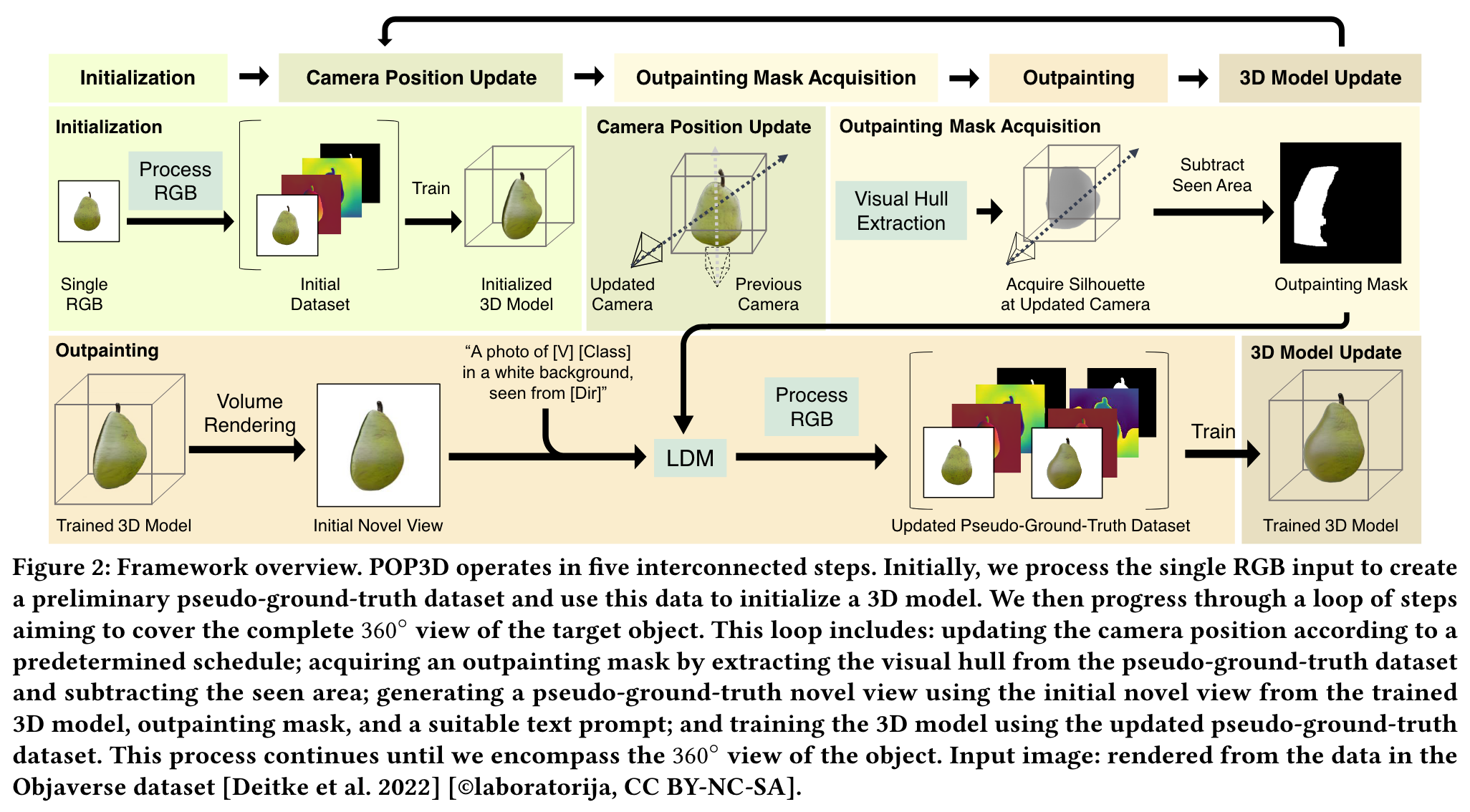

[signed-distance-function monosdf text2image diffusion nerf sdf deep-learning dreambooth image2image 3d This is my reading note for 360 Reconstruction From a Single Image Using Space Carved Outpainting. This paper proposes a method of 3D reconstruction from a single image. To the it represents the 3D object by NERF and iteratively update the NERF by rendering new view using Dream booth.

Introduction

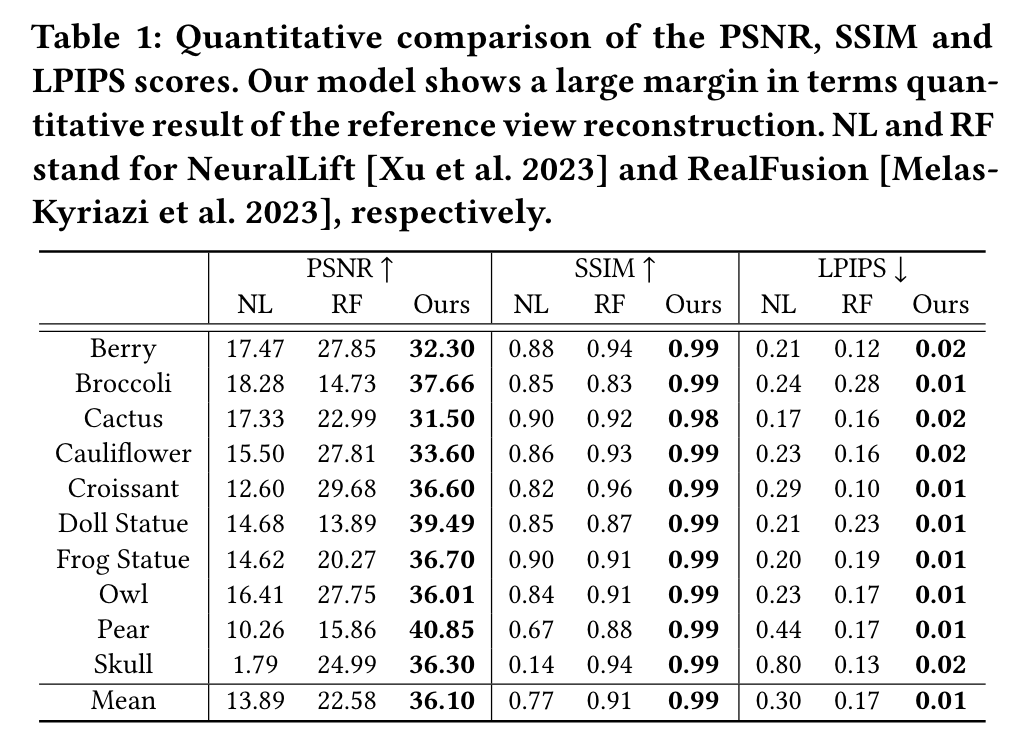

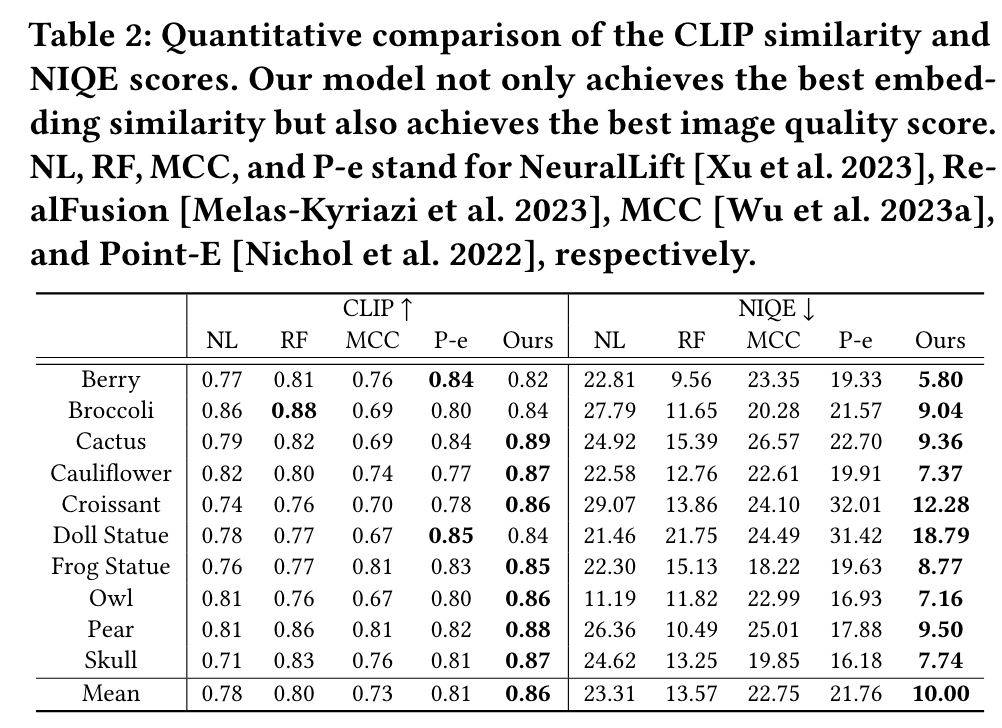

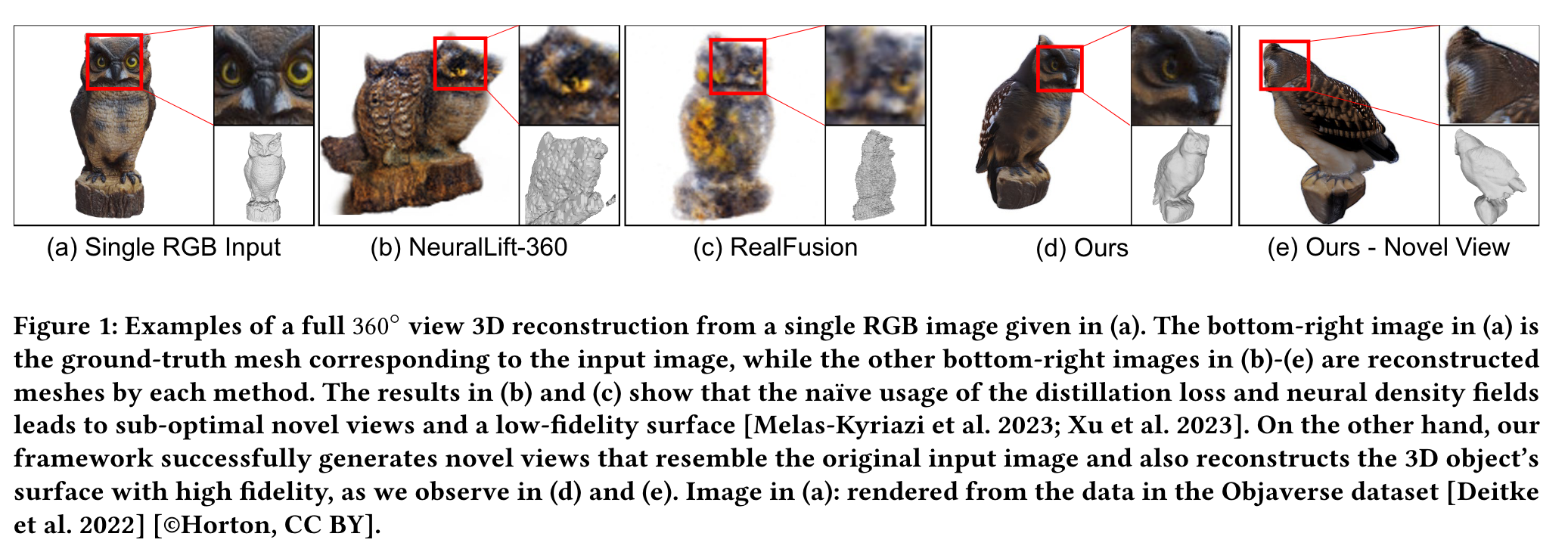

We introduce POP3D, a novel framework that creates a full 360◦ view 3D model from a single image. POP3D resolves two prominent issues that limit the single-view reconstruction. Firstly, POP3D offers substantial generalizability to arbitrary categories, a trait that previous methods struggle to achieve. Secondly, POP3D further improves reconstruction fidelity and naturalness, a crucial aspect that concurrent works fall short of. Our approach marries the strengths of four primary components: (1) a monocular depth and normal predictor that serves to predict crucial geometric cues, (2) a space carving method capable of demarcating the potentially unseen portions of the target object, (3) a generative model pretrained on a large-scale image dataset that can complete unseen regions of the target, and (4) a neural implicit surface reconstruction method tailored in reconstructing objects using RGB images along with monocular geometric cues. The combination of these components enables POP3D to readily generalize across various in-the-wild images and generate state-of-the-art reconstructions, outperforming similar works by a significant margin (p. 1)

Related Work

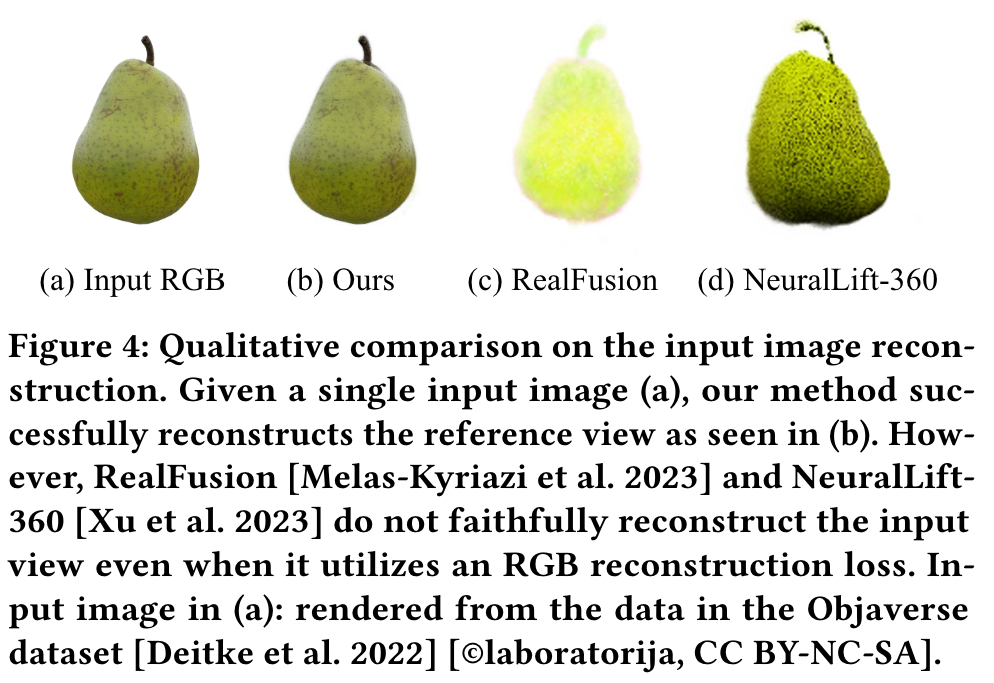

Concurrent methods [Deng et al. 2023; Melas-Kyriazi et al. 2023; Xu et al. 2023] that leverage a large-scale image prior [Rombach et al. 2022] via a distillation loss [Poole et al. 2023] frequently fall short of faithfully reconstructing the input view. This discrepancy arises as the distillation loss interferes with the RGB reconstruction loss of the input view and their limited target resolution of the reconstruction further exacerbates this problem. Furthermore, their use of naïve neural density fields often leads to low-fidelity surface reconstruction. (p. 2)

Few-View-to-3D Reconstruction

However, without dense camera views, training a neural radiance field becomes a severely underconstrained problem. When only given a few views, such models may overfit to each given view resulting in a broken geometry and blurry noise when rendering novel views [Jain et al. 2021]. (p. 3)

Single-View-to-3D Reconstruction

Most of the early work that reconstruct 3D models from a single image rely on the visible information given in an image such as shading [Zhang et al. 1999], texture [Loh 2006], or defocus [Favaro and Soatto 2005]. Recent works use a more general prior in order to generate the invisible parts of an input image. For instance, some methods use 3D datasets to learn a 3D prior that can be used for reconstruction [Choy et al. 2016; Girdhar et al. 2016; Groueix et al. 2018; Saito et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2018; Xie et al. 2019]. (p. 3)

To overcome the issues arising from needing a 3D training dataset, methods that learn 3D structures from image collections have been introduced However, they either need further annotations such as semantic key points and segmentation masks [Kanazawa et al. 2018] or multi-view images of the same scene with accurate camera parameters [Chan et al. 2023; Gu et al. 2023; Guo et al. 2022; Karnewar et al. 2023; Lin et al. 2023; Vasudev et al. 2022]. Other methods that train with single view per scene are category-specific [Henzler et al. 2019; Jang and Agapito 2021; Pavllo et al. 2023; Wu et al. 2023b; Ye et al. 2021]. (p. 3)

While 3D diffusion models [Shue et al. 2023; Wang et al. 2023b] are also gaining attention, concurrent works [Deng et al. 2023; Melas-Kyriazi et al. 2023; Tang et al. 2023; Xu et al. 2023] attempt to directly use a 2D diffusion model [Rombach et al. 2022] trained on a large-scale image-text dataset [Schuhmann et al. 2022] as a prior for single view reconstruction. To generate unseen regions from the reference view, they heavily rely on a distillation loss similar to the score distillation sampling loss introduced by Poole et al. [2023]. The problem is that the distillation loss is simultaneously applied to views that have overlapping regions from the given single view. This often disrupts the RGB loss and consequently often leads to a poor reconstruction of the input view. While a very recent work [Tang et al. 2023] tries to bypass this problem by projecting the reference image on to the trained 3D representation, novel views far from the reference view tend to lack quality:

- Firstly, they have a low target resolution, (p. 3)

- Secondly, these works use naive neural density functions as their geometry representations, which may produce noisy artifacts due to the lack of a well-defined surface threshold (p. 3)

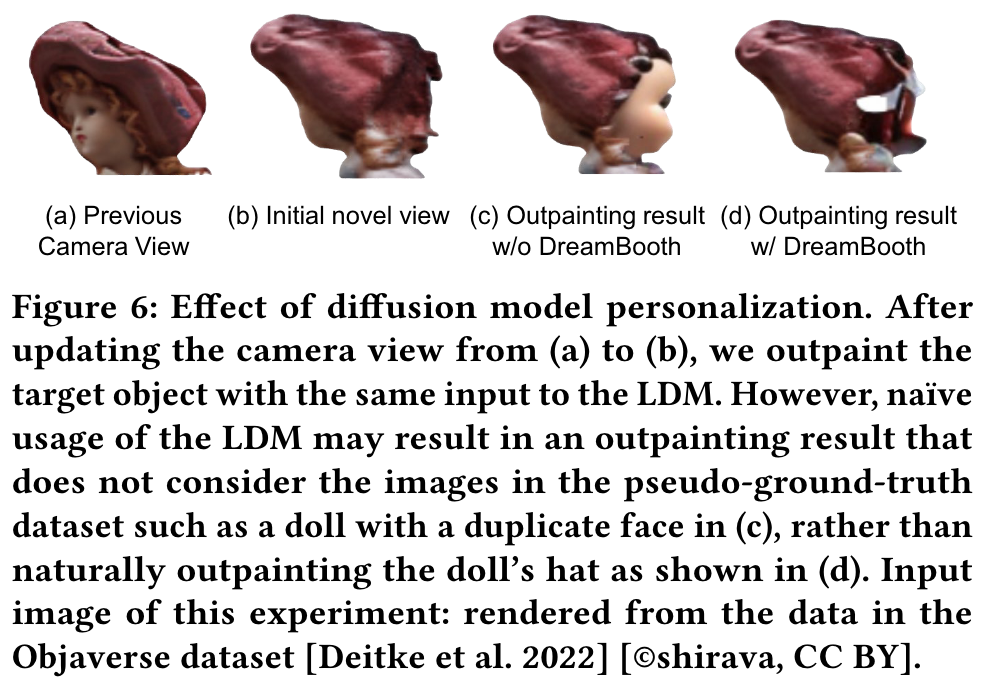

- Lastly, these models only rely on the given single image and its augmentations to personalize the diffusion model using a method similar to Textual Inversion [Gal et al. 2023] in an attempt to generate unseen regions consistent with the input image. In contrast to these methods, our data generation framework allows the use of a state-of-the-art diffusion model personalization method, DreamBooth [Ruiz et al. 2023], that requires multiple views of the same object by using multi-view pseudo-ground-truth images, which allows for a better personalization qualit (p. 3)

Proposed Method

Our key idea is to progressively outpaint the unseen regions of the object by synthesizing their color and geometric information. (p. 4)

- In the initialization step, we estimate the depth and normal maps of the input image and lift it to a 3D view.

- Then, we update the camera position to a nearby viewpoint that has not been seen before, and obtain an outpainting mask that indicates the region to be outpainted using space carving [Kutulakos and Seitz 1999].

- Next, we outpaint the masked region by generating its color and geometric information using a latent diffusion model (LDM) [Rombach et al. 2022].

- Finally, we update the 3D model of the object using the outpainted information. We repeat these steps until we cover the entire 360◦ of the object. (p. 4)

To represent the shape and appearance of a 3D object, we adopt VolSDF [Yariv et al. 2021], which represents a 3D object using a pair of neural networks. Specifically, to represent the geometry of an object, we use a neural network modeling a signed distance function (SDF) 𝑓𝜃 : 𝑥 ↦→ 𝑠, which maps a 3D point 𝑥 ∈ R3 to its signed distance 𝑠 ∈ R to the surface. To account for the appearance, we use another neural network that models a radiance function 𝐿𝜃 (x, nˆ, zˆ) where nˆ is the spatial gradient of the SDF at point x. zˆ is the global geometry feature vector same as in Yariv et al. [2020]. Unlike VolSDF, we do not give the viewing direction as input to 𝐿𝜃 and ignore view-dependent color changes as a single image does not provide view-dependent lighting information and conventional outpainting methods do not account for view dependency. (p. 4)

As 3D model generation from a single image is an extremely ill-posed task, we impose a couple of assumptions to restrict the possible outcomes of the reconstruction results. First, we assume that the target object lies within a cube, which has its center at the origin, and edges of length 2 aligned with the coordinate axes, and initialize the object as a unit sphere following Atzmon and Lipman [2020]. We also assume a virtual camera looking at the target 3D object during our 3D reconstruction process. Specifically, we place the camera on a sphere of radius 3 to point at the origin and parameterize its position using spherical coordinate angles. The field of view (FoV) of the camera is set to 60◦ assuming that the camera parameters of the input image are not given. (p. 4)

Initialization

Specifically, given 𝐿0, we first extract the foreground object by estimating a binary mask 𝑀0 using an off-the-shelf binary segmentation method [Lee et al. 2022]. We then estimate the depth map 𝐷0 and the normal map 𝑁0 for the foreground object using off-the-shelf monocular depth and normal estimators [Bhat et al. 2023; Eftekhar et al. 2021]. Using the estimated depth and normal maps, and binary mask, we estimate an initial 3D model. The pseudo-ground-truth dataset is iteratively updated in the following steps to progressively reconstruct the 3D model of a target object. For training the implicit representation, we adopt the approach of MonoSDF [Yu et al. 2022] with a slight modification to consider the mask 𝑀0 (p. 5)

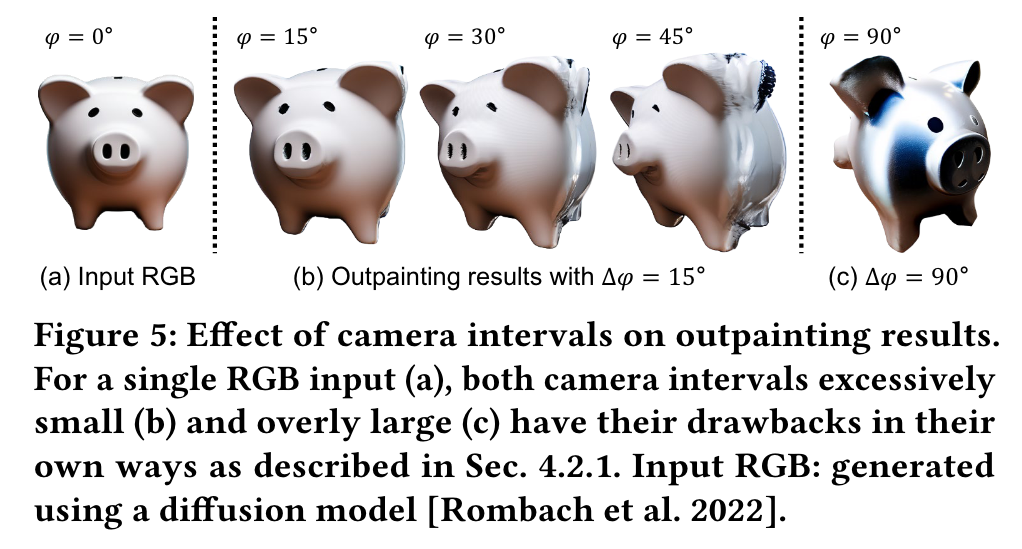

Camera Position Update

However, we found that an excessively small or large interval may detrimentally affect the output. Hence, we use an interval of 45◦ degrees in our experiments, (p. 5)

Outpainting Mask Acquisition

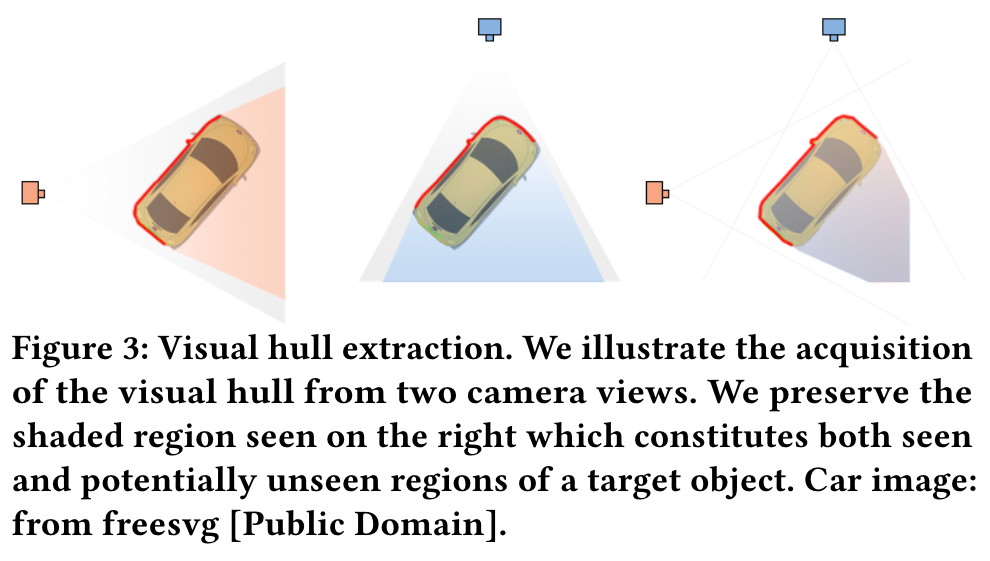

In order to generate the appearance and shape of unseen regions seamlessly, the areas designated for outpainting need to be appropriately chosen. To address this, we leverage the concept of the visual hull [Laurentini 1994]. The visual hull provides a rough approximation of the object’s shape derived from the object’s silhouettes from different viewpoints. To create our outpainting mask, we subtract the observed regions from this initial mask, leaving only the potentially new visible areas. (p. 5)

Visual Hull Computation via Space Carving. For the computation of the visual hull [Laurentini 1994], we use a depth-based voxel carving method driven by a voting scheme (p. 5)

Foreground Mask Computation via Warping Operation. Since 𝑀VH 𝑖 contains both seen and unseen regions, we should subtract out the seen region in order to obtain our outpainting mask 𝑀˜ 𝑖. This is achieved by using a warping operation to compute the foreground mask 𝑀FG 𝑖 in the target view. The process involves rendering the depth from the previous viewpoints S0:𝑖−1, lifting the image points to the 3D space, and subsequently projecting the lifted points to the target view 𝜙𝑖. To mitigate aliasing during the warping process, we scale up the image by a scaling factor of 8. We account for visibility and do not warp pixels not visible from the target viewpoint via back-point culling. (p. 5)

Pseudo-Ground-Truth Generation

In order to reconstruct the 360◦ shape and appearance of the target object, we generate pseudo-ground-truth images to fill in the unseen parts of the object. For this purpose, we use a pretrained state-ofthe-art generative model. Specifically, we use the Latent Diffusion Model (LDM) [Rombach et al. 2022] that takes an RGB image, a mask condition, and a text condition as input and outputs an RGB image following the input conditions.

However, naïvely using a pretrained diffusion model may result in outpainting results that do not resemble the reference image. To generate pseudo-ground-truth images that are coherent to the given single view, we adopt a personalization technique outlined in DreamBooth [Ruiz et al. 2023]. (p. 6)

As the inputs to the personalized LDM, we use:

- 𝐼𝑖 the RGB image rendered from the trained model at the updated camera view,

- 𝑀˜ 𝑖 the outpainting mask at the updated camera view, as detailed in Section 3.3, and

- a text prompt designed to generate view-consistent results. For the text condition, we utilize a prompt structured as “A photo of [V] [Class] in a white background, seen from [Dir]” where [V] represents the personalized unique identifier of the specific object, [Class] refers to a simple class keyword such as ‘hamburger’ or ‘doll’, and [Dir] is a directional keyword such as ‘front’, ‘left’, ‘right’ and ‘behind’ used to guide the generation following the approach of Poole et al. [2023]. (p. 6)

3D Model Update

Using the updated pseudo-ground-truth dataset P, we train the SDF 𝑓𝜃 and neural radiance field 𝐿𝜃 following MonoSDF [Yu et al. 2022]. After retraining the target 3D model, we return to the camera position update step described in Sec. 3.2, and continue the loop until we go through the whole camera schedule S. (p. 6)

Experiment