RoBERTa A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach

[bert llm deep-learning transformer roberta This is my reading note for RoBERTa: A Robustly Optimized BERT Pretraining Approach. This paper revisits the design choice of BERT. It provides that 1) adding more data; 2) using larger batch size; 3) training for more iterations could significantly improves the performance. In addition, using longer sentence/context could also improve performance and next sentence prediction is no longer useful.

Introduction

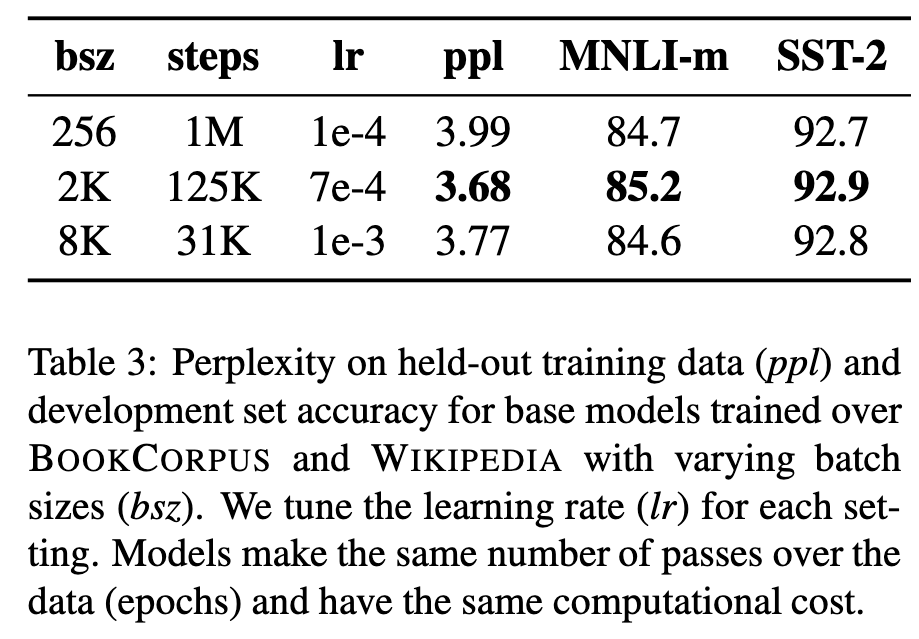

We present a replication study of BERT pretraining (Devlin et al., 2019) that carefully measures the impact of many key hyperparameters and training data size. We find that BERT was significantly undertrained, and can match or exceed the performance of every model published after it. (p. 1)

Our modifications are simple, they include:

- training the model longer, with bigger batches, over more data;

- removing the next sentence prediction objective;

- training on longer sequences; and

- dynamically changing the masking pattern applied to the training data. (p. 1)

Background

Setup

BERT takes as input a concatenation of two segments (sequences of tokens), x_1, . . . , x_N and y_1, . . . , y_M . Segments usually consist of more than one natural sentence. The two segments are presented as a single input sequence to BERT with special tokens delimiting them: [CLS ], x_1, . . . , x_N , [SEP ], y_1, . . . , y_M , [EOS ]. M and N are constrained such that M + N < T , where T is a parameter that controls the maximum sequence length during training. (p. 2)

Training Objectives

During pretraining, BERT uses two objectives: masked language modeling and next sentence prediction. (p. 2)

Masked Language Model (MLM)

A random sample of the tokens in the input sequence is selected and replaced with the special token [MASK ]. The MLM objective is a cross-entropy loss on predicting the masked tokens. BERT uniformly selects 15% of the input tokens for possible replacement. (p. 2)

Next Sentence Prediction (NSP)

NSP is a binary classification loss for predicting whether two segments follow each other in the original text. (p. 2)

Optimization

BERT is optimized with Adam (Kingma and Ba, 2015) using the following parameters: β_1 = 0.9, β_2 = 0.999, ǫ = 1e-6 and L2 weight decay of 0.01. The learning rate is warmed up over the first 10,000 steps to a peak value of 1e-4, and then linearly decayed. BERT trains with a dropout of 0.1 on all layers and attention weights, and a GELU activation function (Hendrycks and Gimpel, 2016). Models are pretrained for S = 1,000,000 updates, with minibatches containing B = 256 sequences of maximum length T = 512 tokens. (p. 2)

Experimental Setup

Implementation

We additionally found training to be very sensitive to the Adam epsilon term, and in some cases we obtained better performance or improved stability after tuning it. Similarly, we found setting β2 = 0.98 to improve stability when training with large batch sizes. (p. 3)

Evaluation

GLUE

Tasks are framed as either single-sentence classification or sentence-pair classification tasks. (p. 3)

SQuAD

The Stanford Question Answering Dataset (SQuAD) provides a paragraph of context and a question. The task is to answer the question by extracting the relevant span from the context. (p. 3)

RACE

In RACE, each passage is associated with multiple questions. For every question, the task is to select one correct answer from four options. (p. 4)

Training Procedure Analysis

Static vs. Dynamic Masking

We find that our reimplementation with static masking performs similar to the original BERT model, and dynamic masking is comparable or slightly better than static masking. (p. 4)

Model Input Format and Next Sentence Prediction

We find that using individual sentences hurts performance on downstream tasks, which we hypothesize is because the model is not able to learn long-range dependencies. (p. 5)

We find that this setting outperforms the originally published BERTBASE results and that removing the NSP loss matches or slightly improves downstream task performance, in contrast to Devlin et al. (2019). It is possible that the original BERT implementation may only have removed the loss term while still retaining the SEGMENT-PAIR input format. (p. 5)

Finally we find that restricting sequences to come from a single document (DOC-SENTENCES) performs slightly better than packing sequences from multiple documents (FULL-SENTENCES). (p. 5)

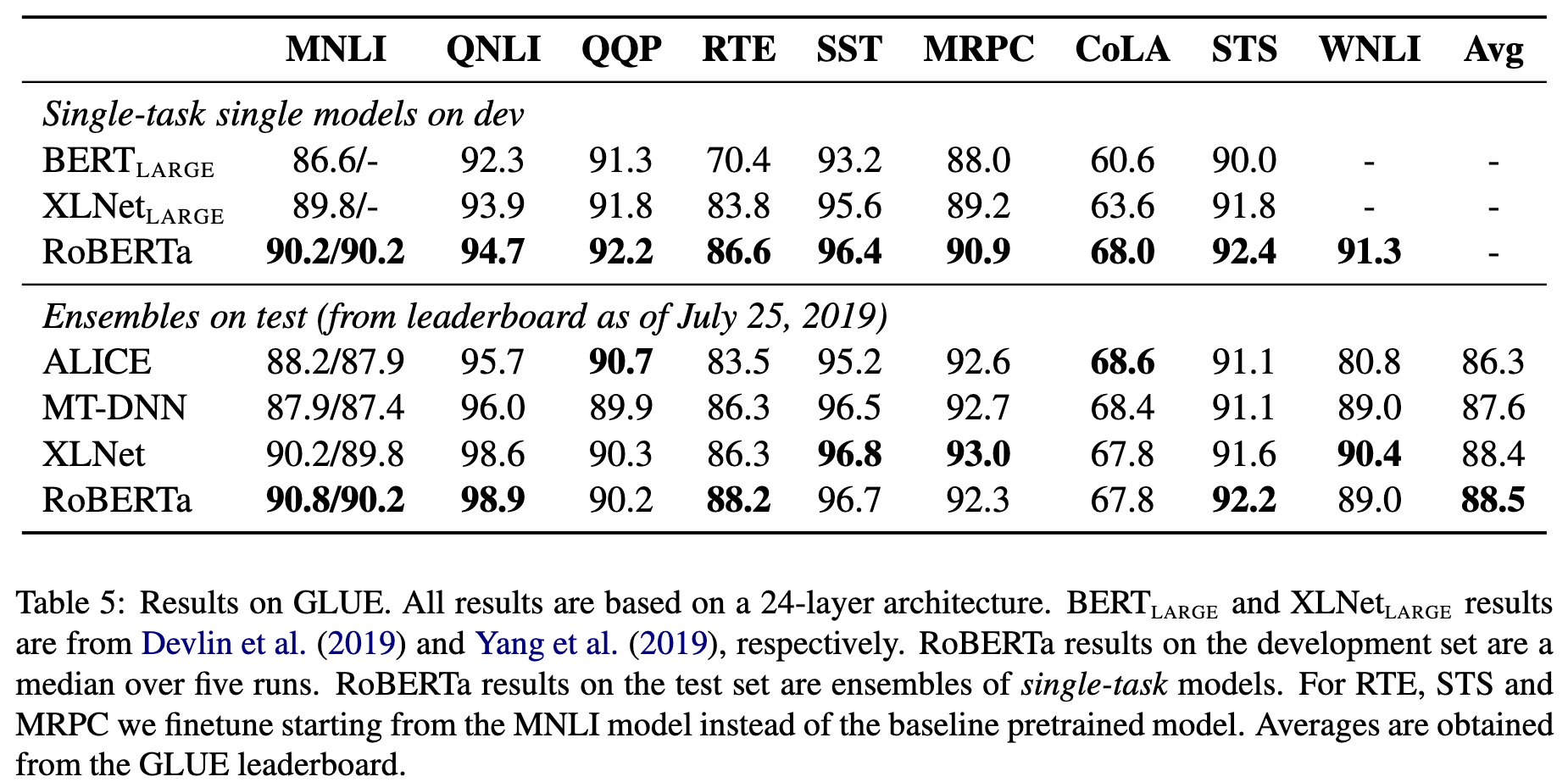

Training with large batches

Past work in Neural Machine Translation has shown that training with very large mini-batches can both improve optimization speed and end-task performance when the learning rate is increased appropriately (Ott et al., 2018). We observe that training with large batches improves perplexity for the masked language modeling objective, as well as end-task accuracy. (p. 6)

Text Encoding

Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) (Sennrich et al., 2016) is a hybrid between character- and word-level representations that allows handling the large vocabularies common in natural language corpora. Instead of full words, BPE relies on subwords units, which are extracted by performing statistical analysis of the training corpus. BPE vocabulary sizes typically range from 10K-100K subword units. (p. 6)

Radford et al. (2019) introduce a clever implementation of BPE that uses bytes instead of unicode characters as the base subword units. Using bytes makes it possible to learn a subword vocabulary of a modest size (50K units) that can still encode any input text without introducing any “unknown” tokens. (p. 6)

The original BERT implementation (Devlin et al., 2019) uses a character-level BPE vocabulary of size 30K, which is learned after preprocessing the input with heuristic tokenization rules. Following Radford et al. (2019), we instead consider training BERT with a larger byte-level BPE vocabulary containing 50K subword units, without any additional preprocessing or tokenization of the input. This adds approximately 15M and 20M additional parameters for BERTBASE and BERTLARGE, respectively. (p. 6)

RoBERTa

Specifically, RoBERTa is trained with dynamic masking (Section 4.1), FULL-SENTENCES without NSP loss (Section 4.2), large mini-batches (Section 4.3) and a larger byte-level BPE (Section 4.4). (p. 6)