Scaling Laws for Generative Mixed-Modal Language Models

[multimodal review deep-learning dataset hubert chichilla-law gpt opt vq-gan vq-vae casual masking cm3leon This is my reading note for Scaling Laws for Generative Mixed-Modal Language Models. This paper provides a study of scaling raw on dataset size and model size in multimodality settings.

Introduction

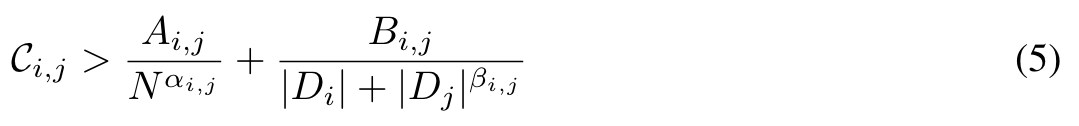

To better understand the scaling properties of such mixed-modal models, we conducted over 250 experiments using seven different modalities and model sizes ranging from 8 million to 30 billion, trained on 5-100 billion tokens. We report new mixed-modal scaling laws that unify the contributions of individual modalities and the interactions between them. (p. 1)

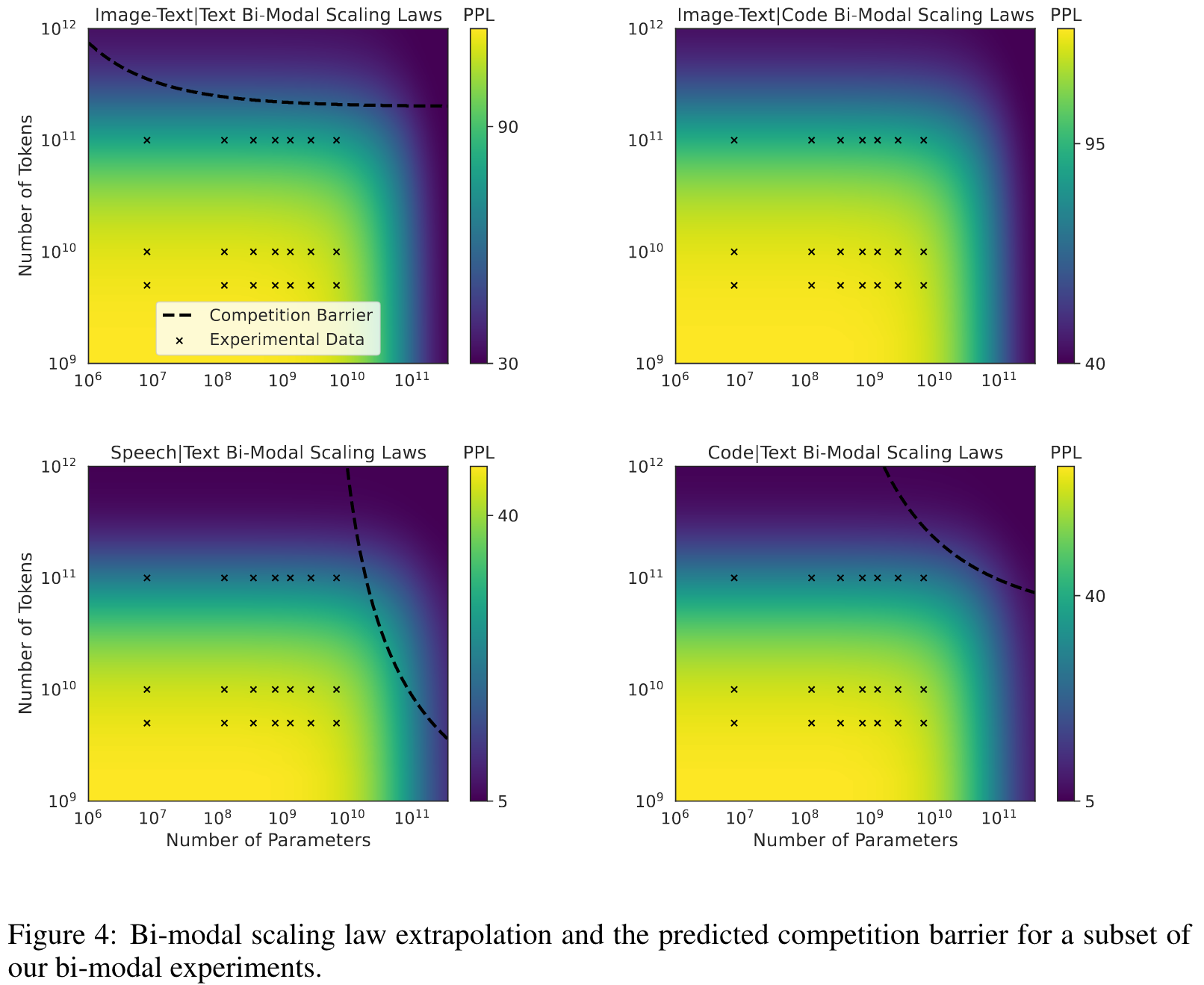

We also report a number of new empirical phenomena that arise during the training of mixed-modal models, including the tendency for the models to prioritize the optimization of a single modality at different stages of training. Our findings demonstrate that these phenomena can be primarily explained through the scaling law of interaction within the mixed-modal model. (p. 2)

RELATED WORK

Neural scaling laws quantify the relationship between model size, dataset size, compute budget, and performance, when training neural networks. Hoffmann et al. (2022) developed a unified formula for scaling laws, and provided recipes for compute-optimal training by adding data-dependent scaling terms unlike previous power law parameterizations. (p. 2)

Interestingly, similar competition and scaling phenomenon have been observed for multi-lingual models. Conneau et al. (2019) observed a “curse of multilinguality,” where training in multiple languages can lead to interference between languages, resulting in decreased performance. Goyal et al. (2021) and Shaham et al. (2022) demonstrated that this interference could occur even on models much smaller than the available training data, but scaling up the model size can improve synergy and alleviate interference. (p. 3)

DEFINITIONS

WHAT IS A MODALITY?

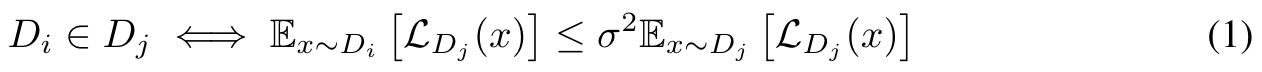

We empirically define modality by comparing the perplexity of one data set to another. Suppose the perplexity of the secondary data set over the probability distribution of the primary set is greater than σ times the mean perplexity of the primary set. In that case, we consider them to be distinct modalities. (p. 3)

UNI-MODAL SCALING LAWS

EMPIRICAL SETTING

DATASETS

Image For all images, we convert them to discrete tokens using the Make-A-Scene visual tokenizer (Gafni et al., 2022), which gives 1024 tokens from an 8192 vocabulary per image. We select a custom subset of 600 million images across Schuhmann et al. (2022), and a custom image-text dataset scraped from Common Crawl. (p. 4)

Speech. We follow a series of preprocessing steps to improve the data quality and remove music and sensitive speech data. We also use a LangID model to select English-only speech. Our public data collection covers various speech styles and content topics, including LibriSpeech (ReadBooks), CommonVoice in Read-Wiki, VoxPopuli from the Parliament domain, and Spotify Podcast and People’s Speech as web speech. (p. 4)

Speech-Text. Many public datasets also come with text aligned with speech. We take ASR and TTS data from Multilingual LibraSpeech and VoxPopuli and form the Speech-Text dataset. (p. 4)

TOKENIZATION

We use a Hidden-Unit BERT (HuBERT) Hsu et al. (2021) model for tokenizing our speech data. HuBERT is a self-supervised learning (SSL) model. It is trained to predict a masked subset of the speech signal using a mask language model objective, and has been found to be effective in learning a combined acoustic and language model over the continuous speech inputs. (p. 4)

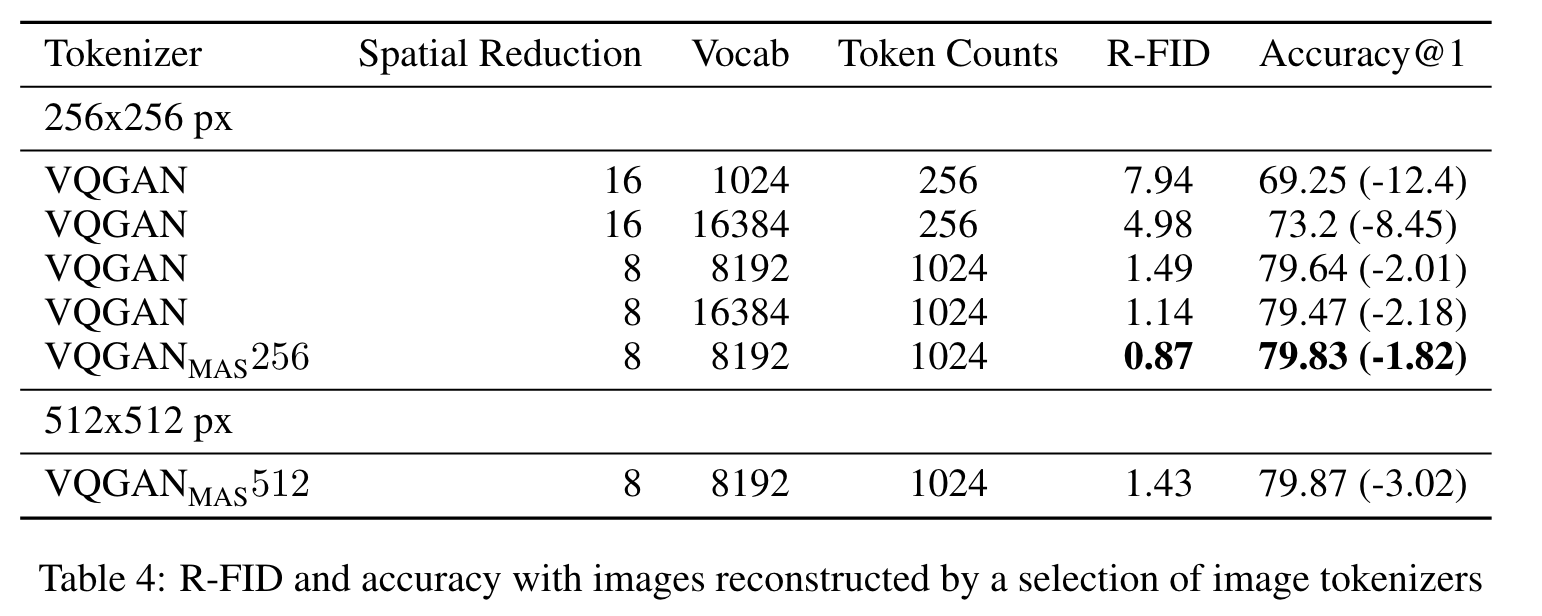

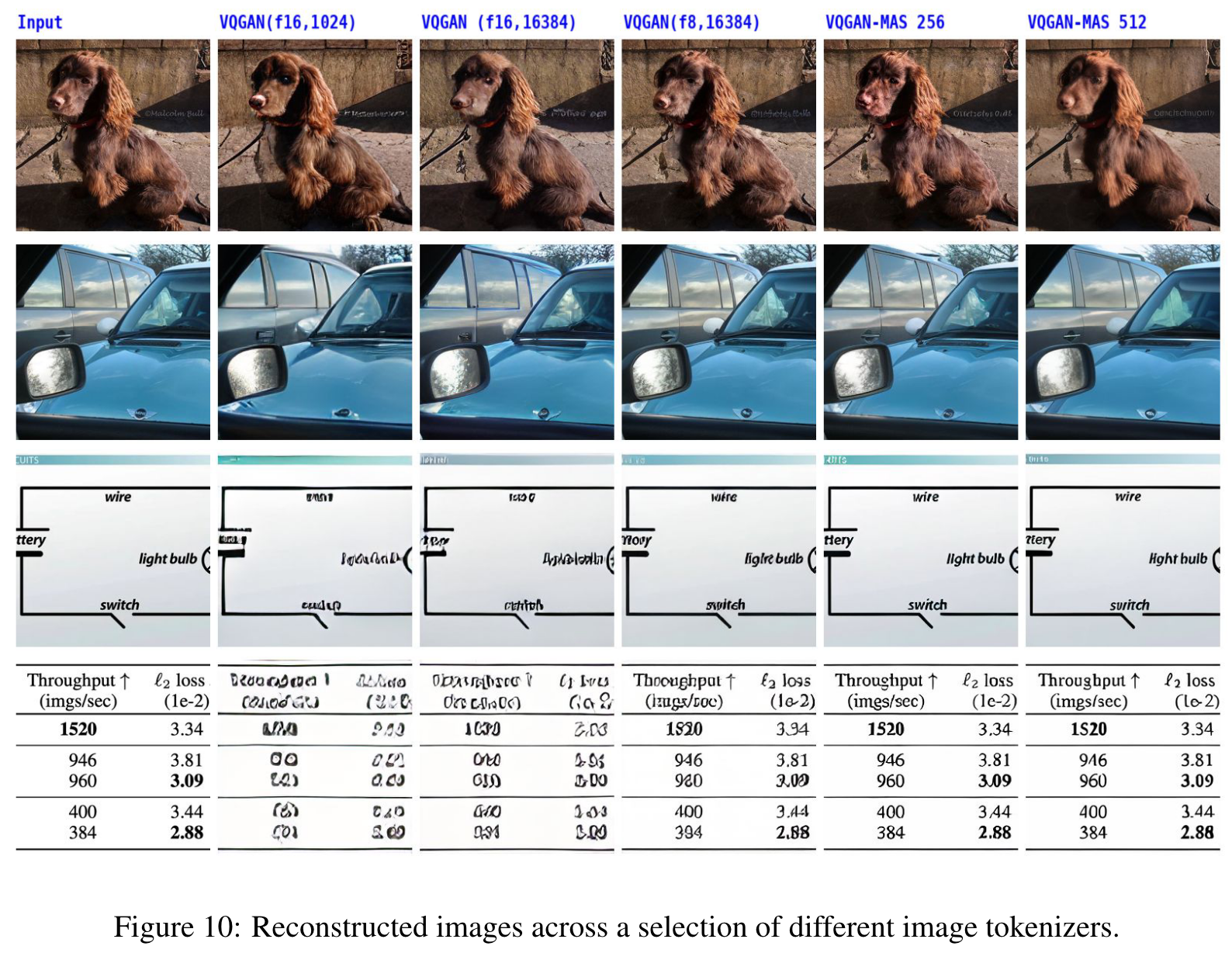

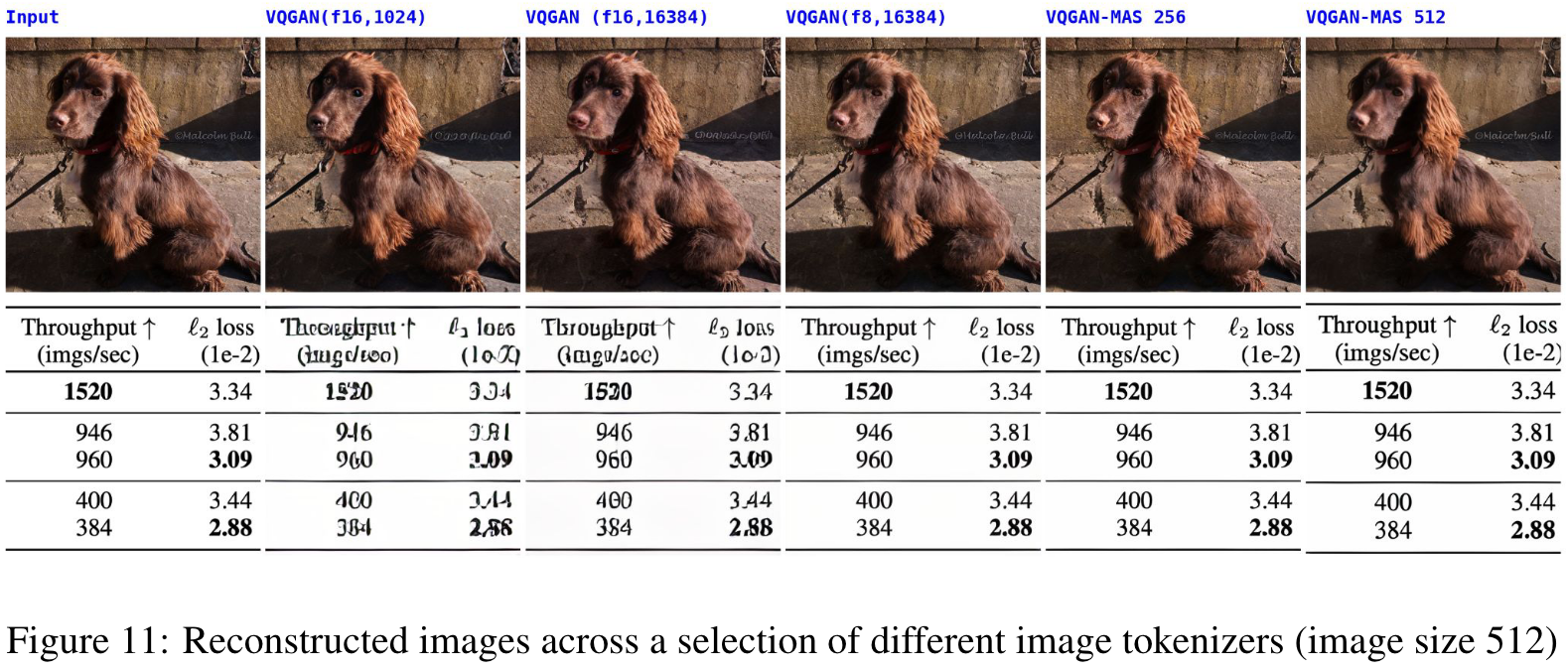

From all the above examples, the reduced spatial reduction is effective for better tokenization; however, it results in a longer token sequence. Another way to increase image representation is to increase the pixel numbers of images. (p. 18)

MODEL ARCHITECTURE

We study the family of decoder-only models described in GPT-3 Brown et al. (2020) and OPT Zhang et al. (2022). We limit ourselves to training up to 6.7 billion-parameter models for all our uni-modal and bi-modal scaling laws and train up to 30B parameters to measure the generalizability of our scaling laws. (p. 5)

CAUSAL MASKING OBJECTIVE

Instead of the traditional left-to-right causal language modeling objective, we use the causal masked objective from Aghajanyan et al. (2022). This provides a form of bidirectional context for sequence infilling, and also supports more aggressive generalization. (p. 5)

TRAINING PROCEDURE

All models were trained using the metaseq1 code base, which includes an implementation of causal masking Zhang et al. (2022). The training used the PyTorch framework Paszke et al. (2019), with fairscale to improve memory efficiency through fully sharded model and optimizer states Baines et al. (2021). The training also uses Megatron-LM Tensor Parallelism Shoeybi et al. (2019) to support large model runs, and we use bf16 Kalamkar et al. (2019) to improve training stability. we performed a single epoch of training (p. 5)

To ensure stable training, we applied gradient clipping with a maximum norm of 1.0 and used the Adam optimizer with β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.98 Kingma & Ba (2015). We used the built-in polynomial decay learning rate scheduler in MetaSeq with 500 warmup updates and the end learning rate set to 10% of the peak learning rate. (p. 5)

To ensure consistent training strategies across our experiments, we implemented a model restart policy using the Aim experiment tracker and callbacks. Specifically, if training perplexities do not decrease after 500 million tokens, the training run is restarted with a reduced learning rate with a factor of 0.8 of the current time step. (p. 5)

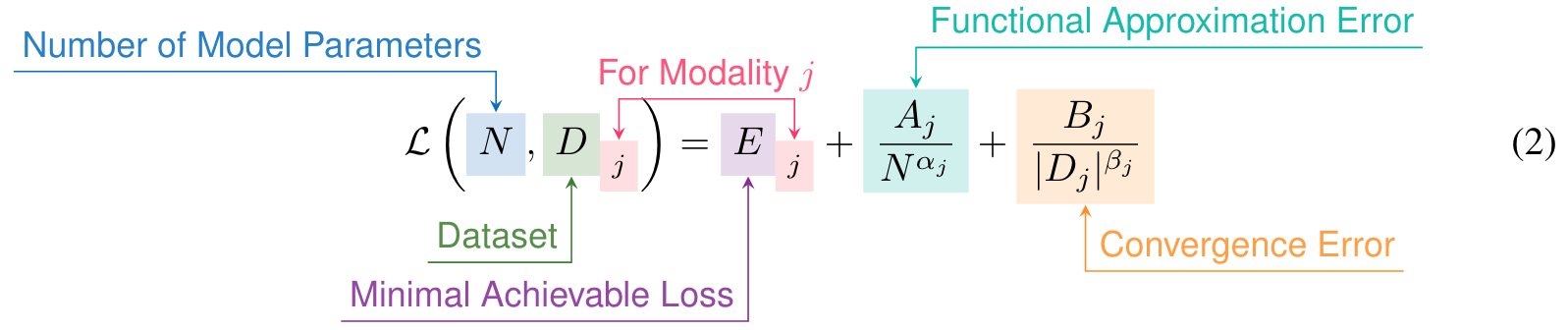

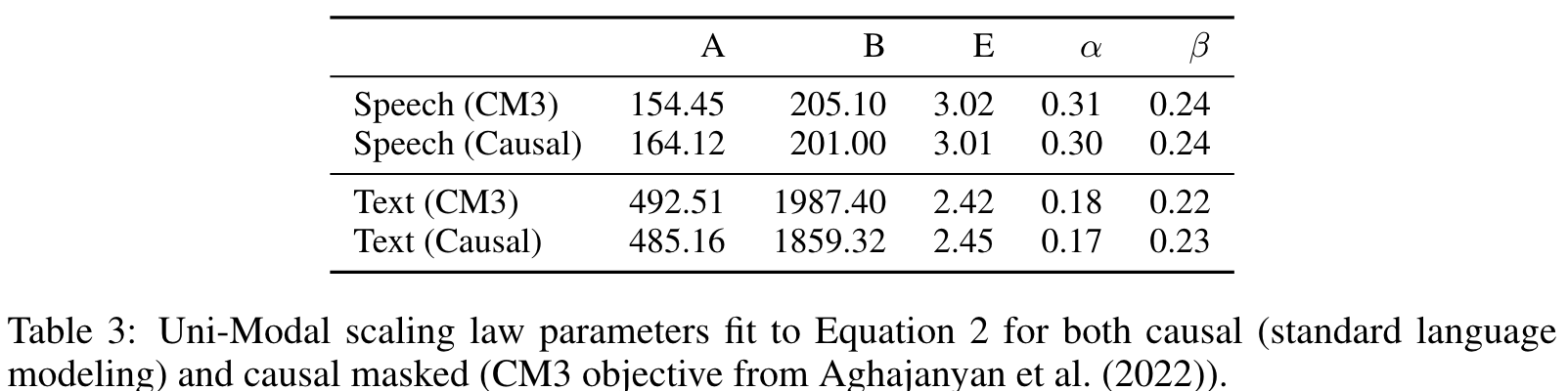

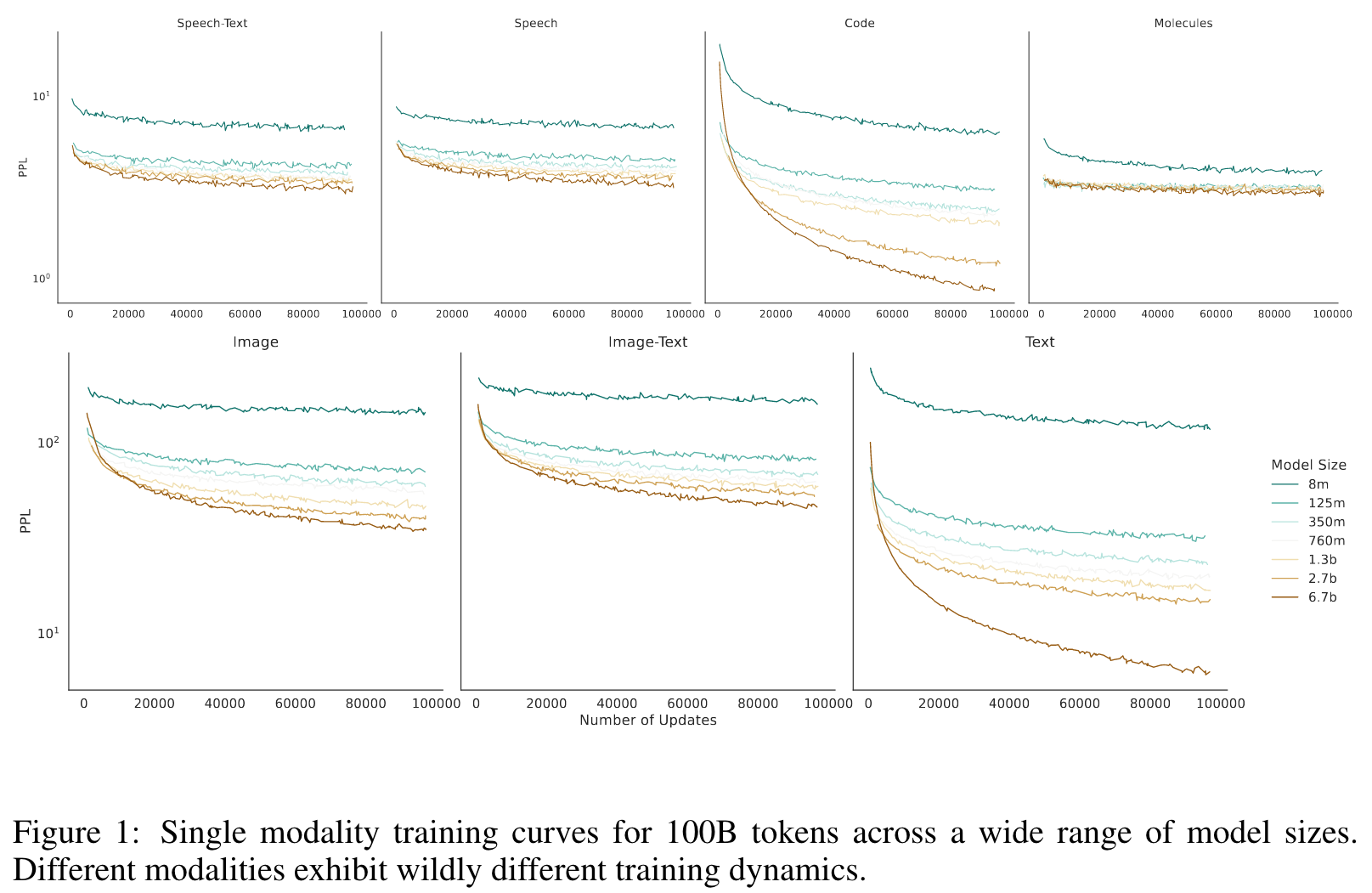

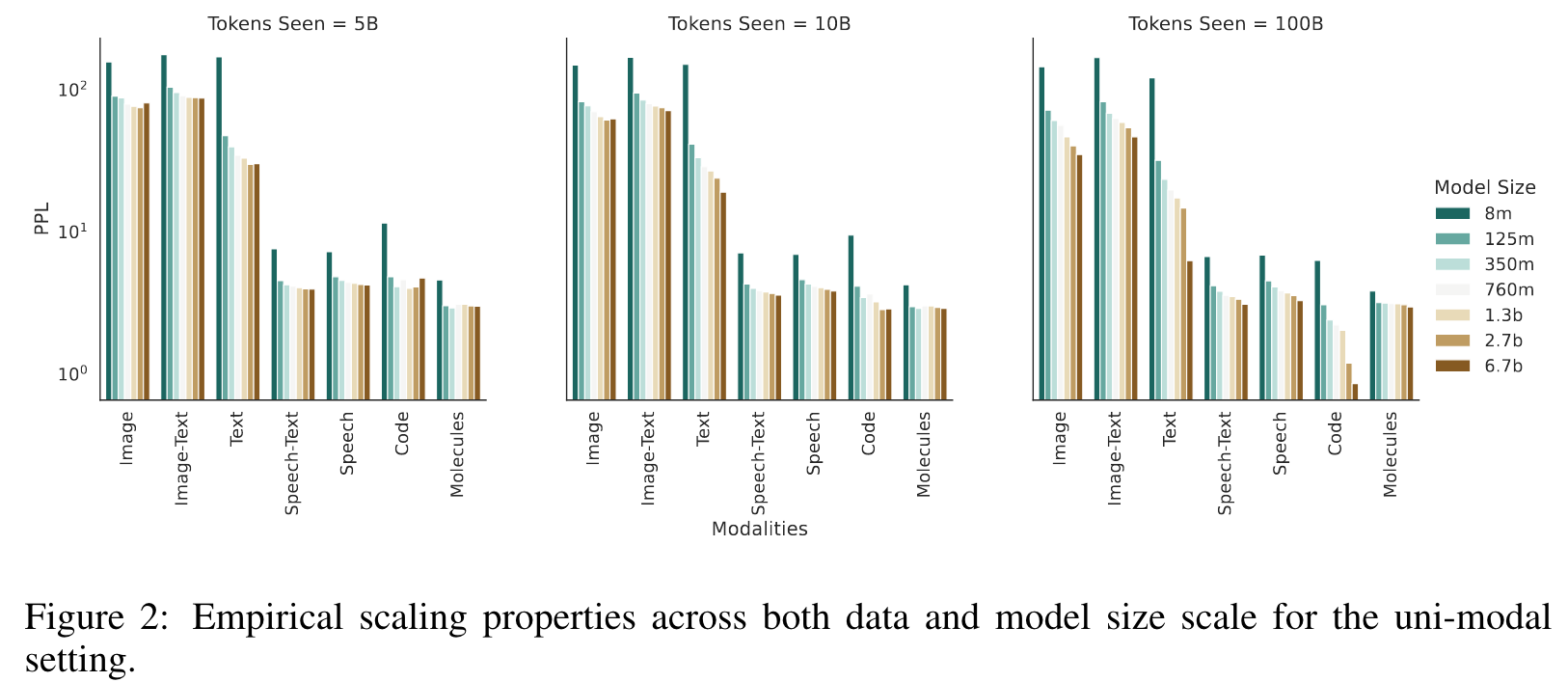

SCALING LAWS

Overall, we see that scaling dynamics are fundamentally different across modalities, scale, and dataset size (which further reinforces our selection of dataset-size-dependent parameterization of scaling laws). (p. 5)

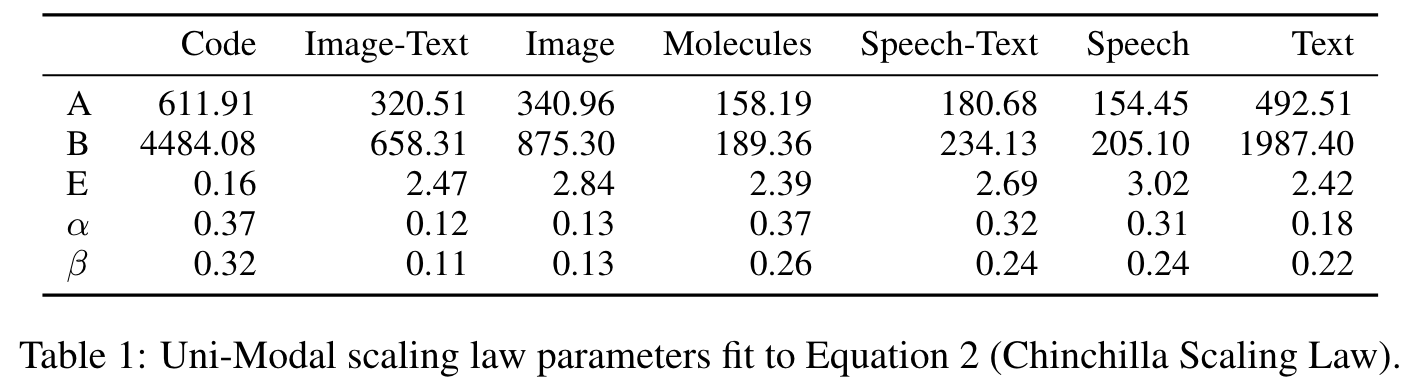

The scaling laws for each modality are presented in Table 1. The parameters for each modality vary significantly (p. 6)

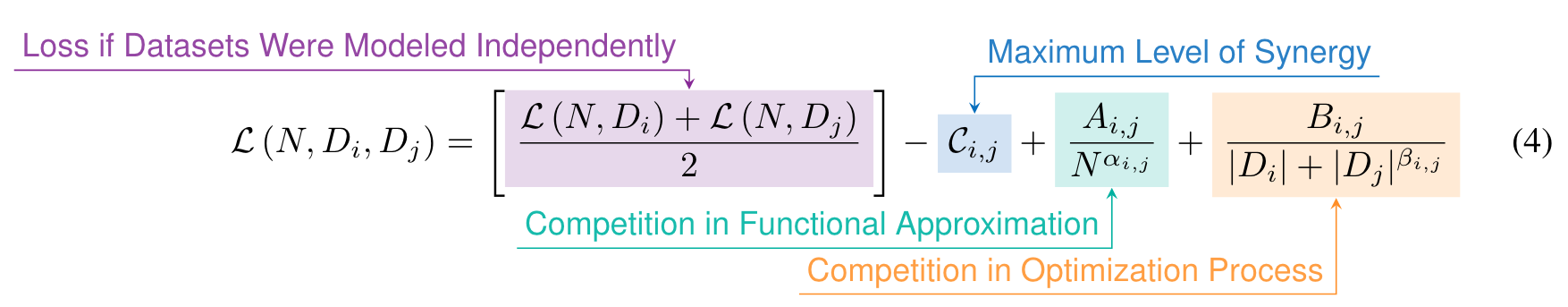

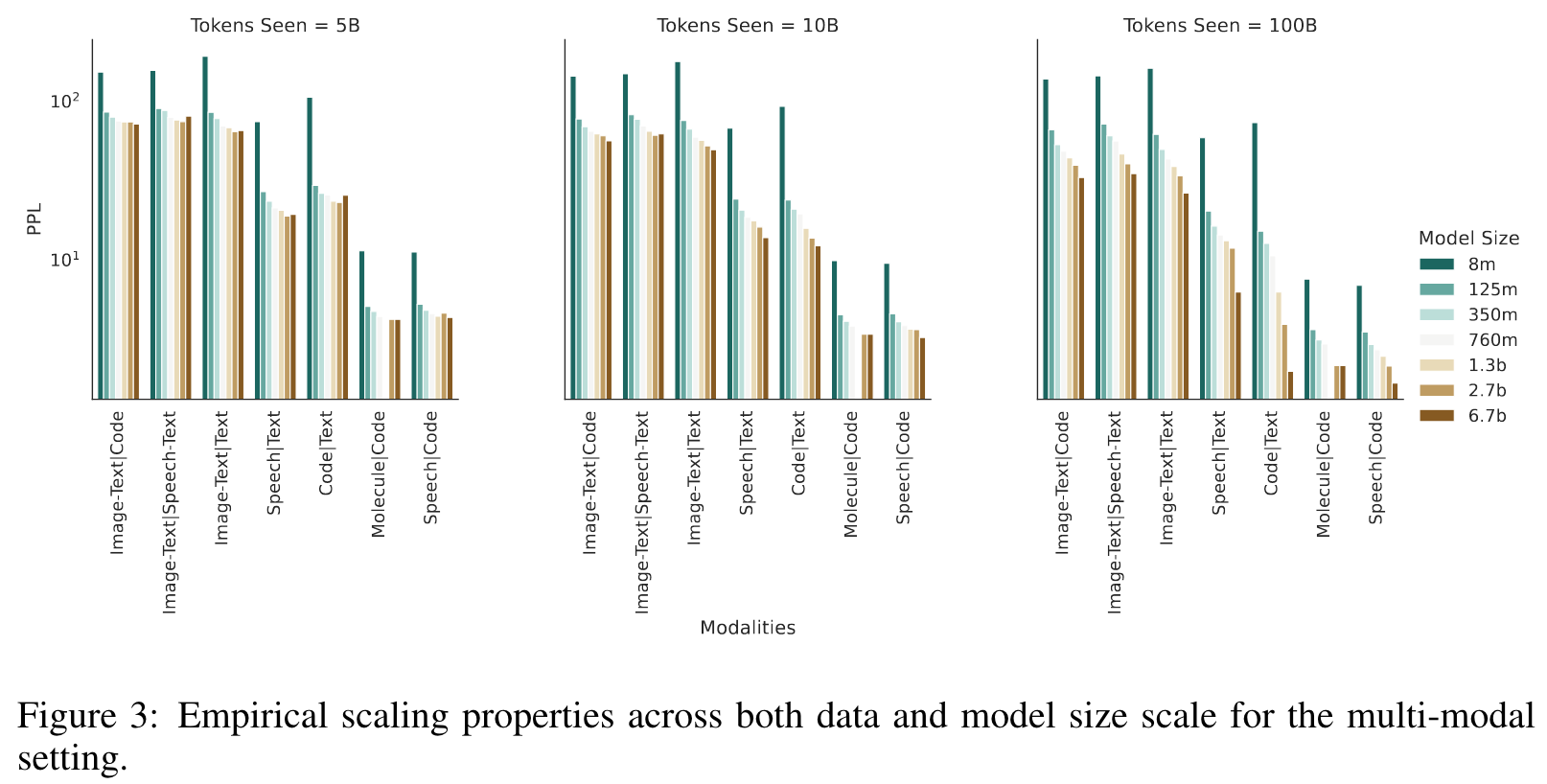

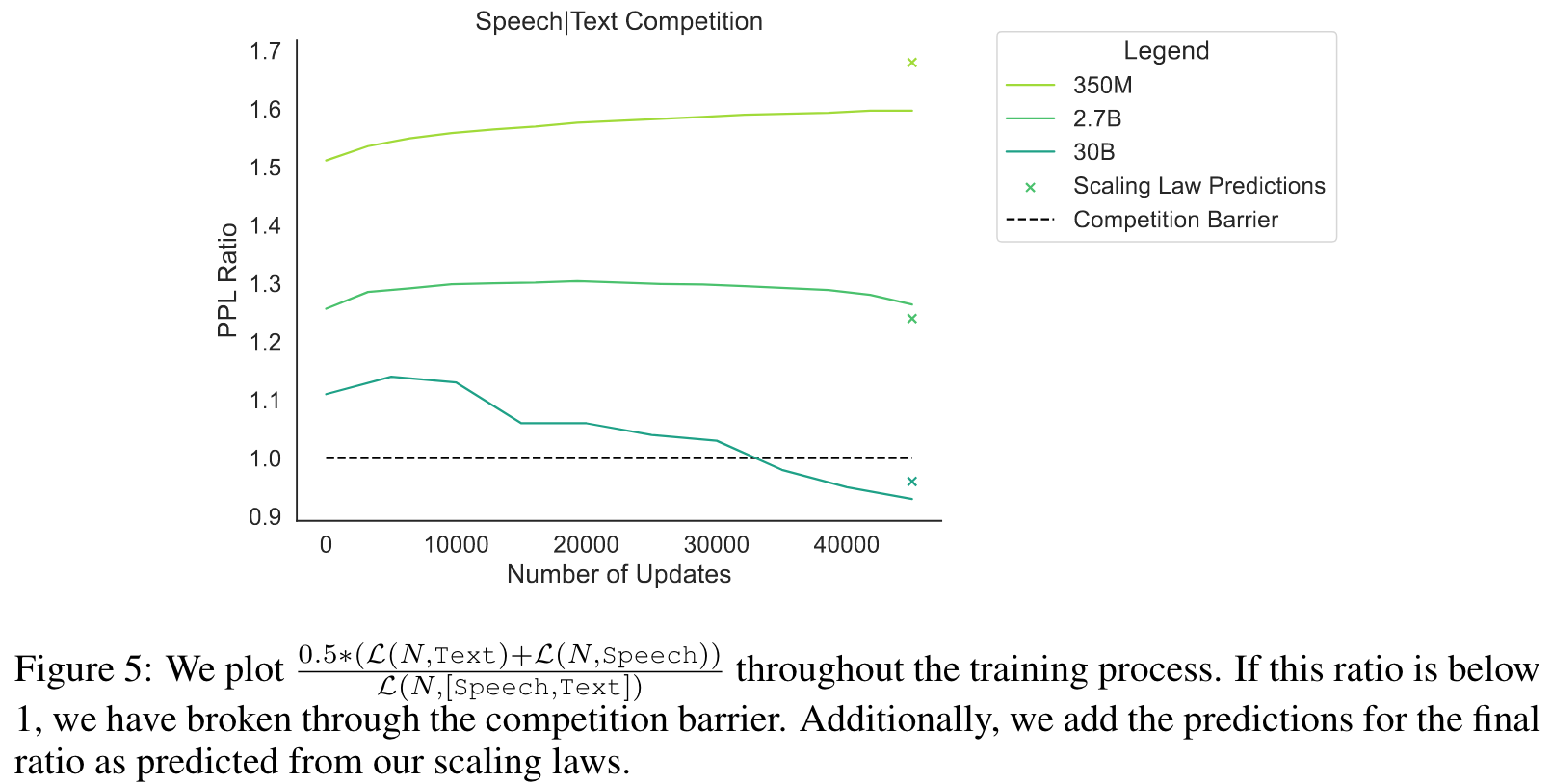

BI-MODAL SCALING LAWS

Given these laws, we can now make predictions about what scale will be required to overcome modal competition and achieve synergy from training on each pair of modalities. By modality competition, we refer to the empirical phenomena of two modalities performing worse than if we trained two individual models on the same number of per-modality tokens. By synergy, we mean the inverse. (p. 7)

| For the Speech | Text coupling, the predicted compute optimal parameters are N = 28.35B and D = 45.12B (p. 9) |

EMERGENT PHENOMENA

Phenomenon 1 Intermittent Coordinate Ascent Like Training

Different source modalities in a multi-modal setting are optimized at different paces, with some modalities even pausing their training progression for a significant amount of steps. (p. 9)

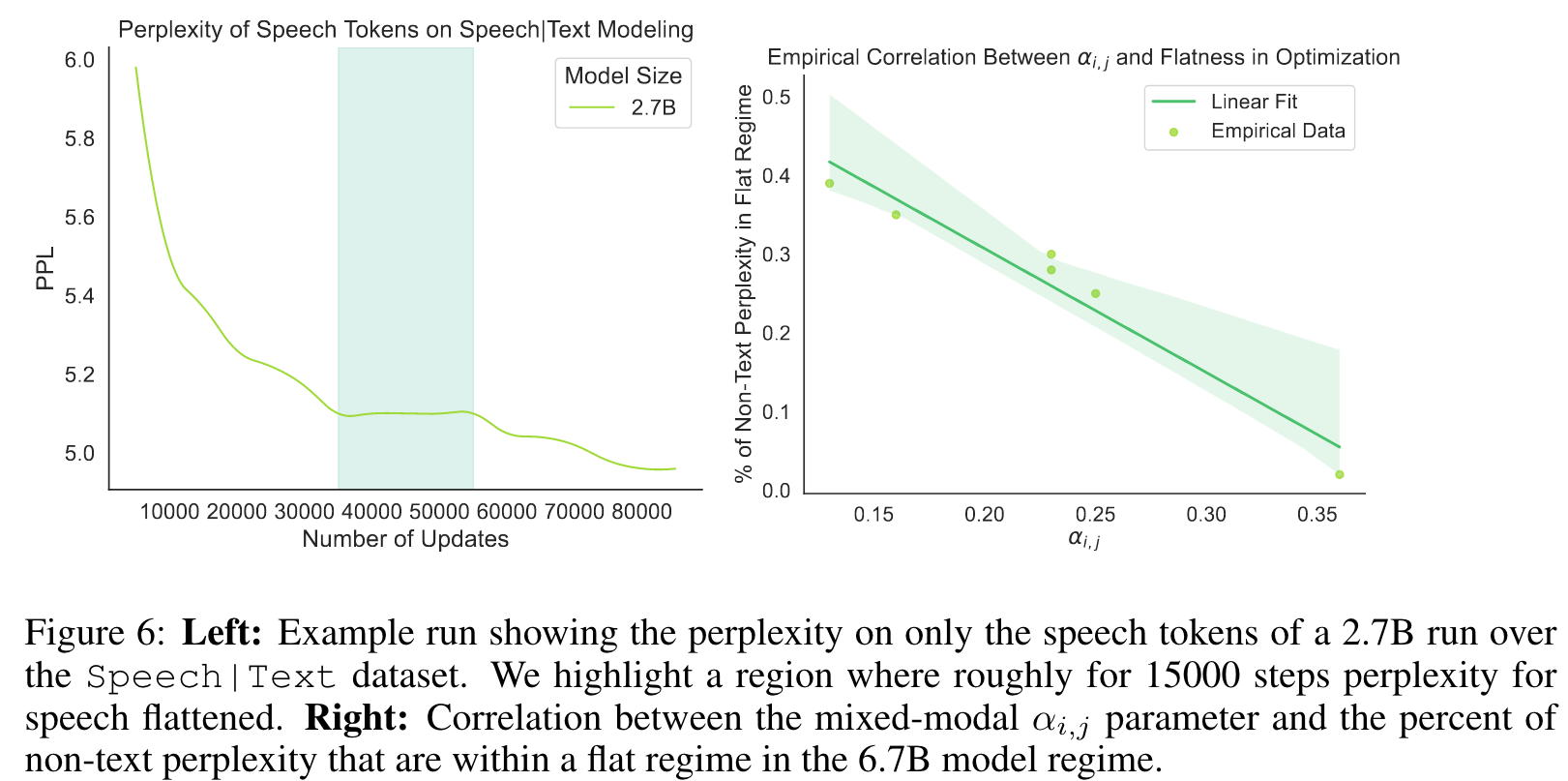

When looking at average perplexity over the dataset, the training dynamics are always consistently smooth and somewhat monotonically decreasing (Figure 5.1). But looking at the sub-perplexities of the modalities shows a different picture; certain modalities flatten out during training (see left figure in Figure 6). (p. 9)

Phenomenon 2 Rate of Phenomena 1 Diminishes Past A Certain Scale

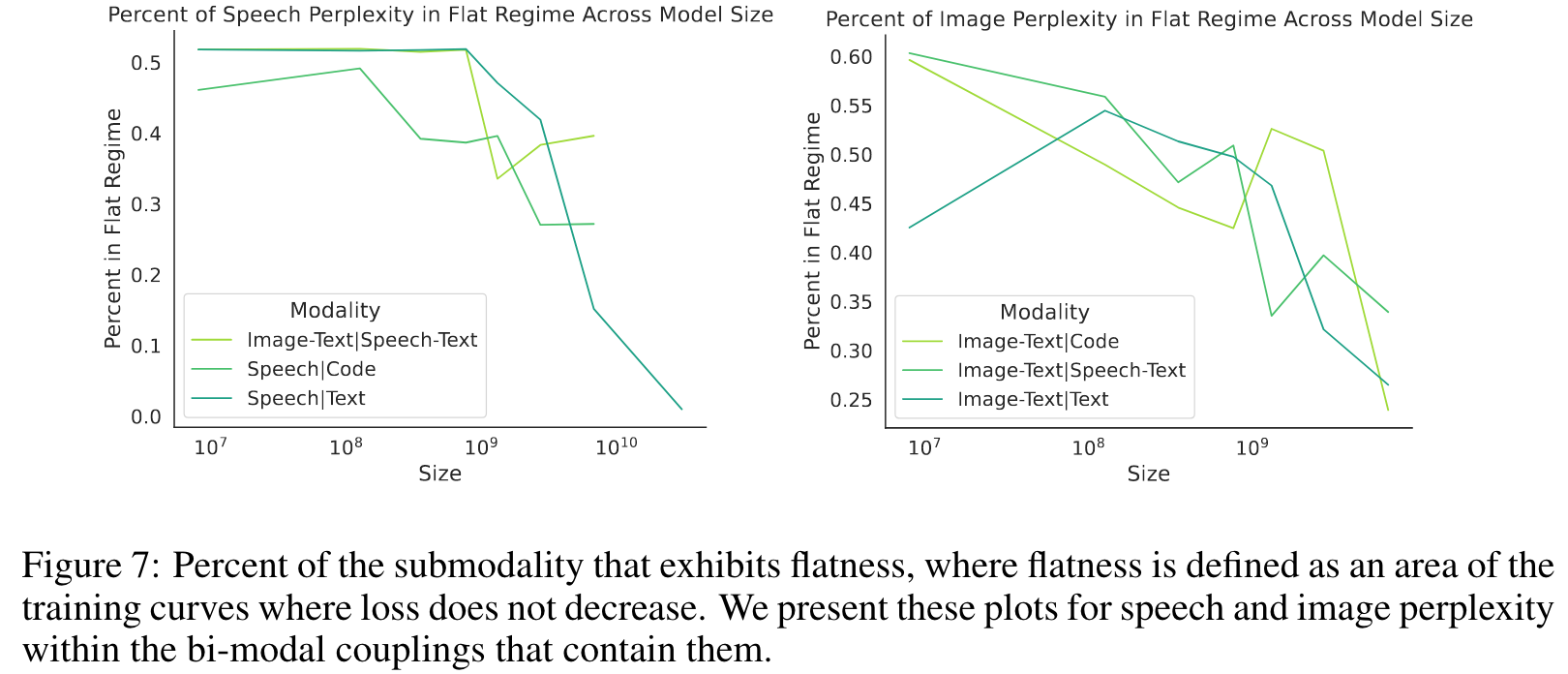

The rate of intermittent coordinate ascent-like training is correlated with scale (N ) and αi,j. (p. 9)

Most of this intermittent coordinate ascent-like training can be reduced by simply increasing the model size. (p. 10)

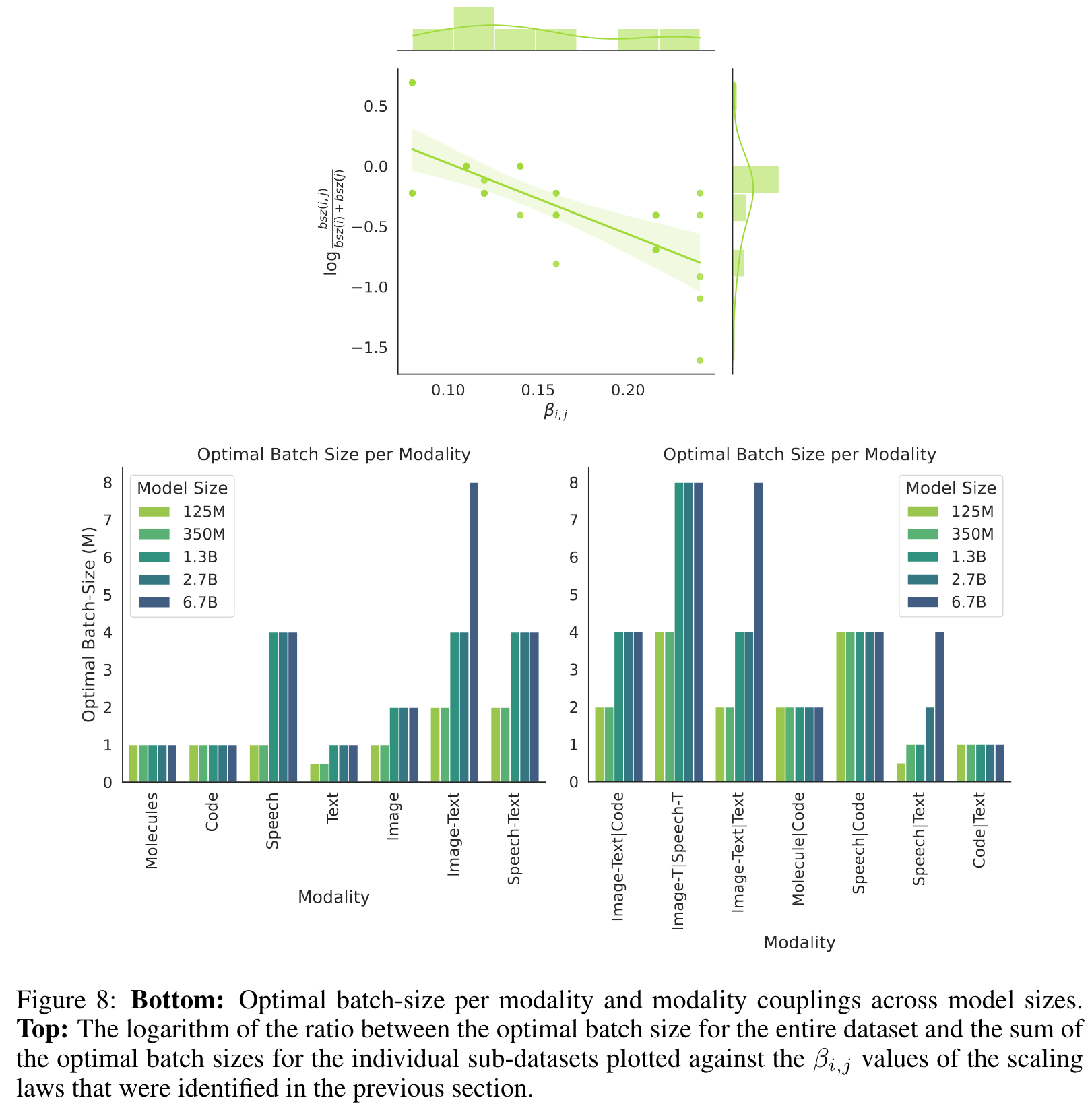

Phenomenon 3 Optimal Batch Size for Modalities i and j is Correlated with βi,j

We fixed the batch size to 1M tokens, but the question of the optimal batch for each modality and modality coupling remains. We found no correlation between αi,j and optimal batch-size. (p. 10)

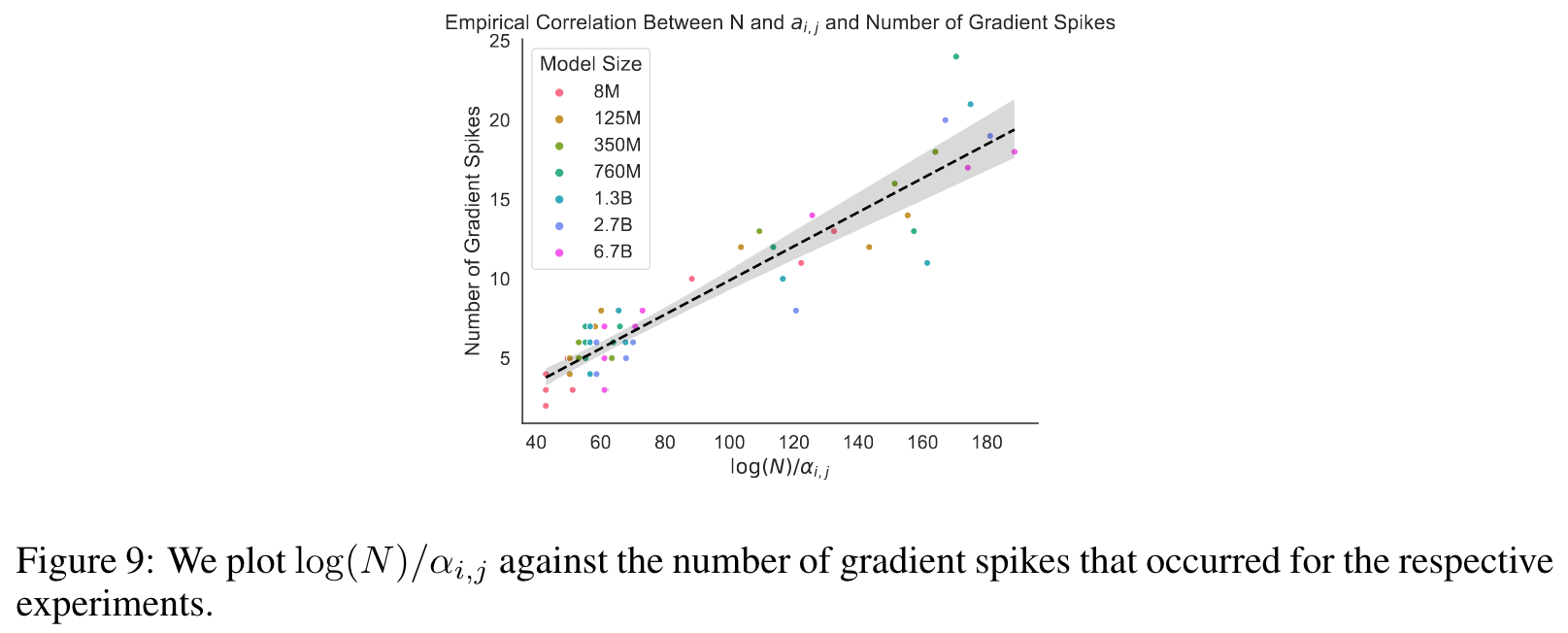

Phenomenon 4 Rate of Deteriorating Training Dynamics is Correlated with αi,j and N

The stability of training can be captured by looking at the total count of gradient norm spikes throughout the lifetime of the training. We hypothesize that lower values of αi,j, reflecting higher competition between modalities, will correlate with more gradient norm spikes. (p. 11)