Efficient Streaming Language Models with Attention Sinks

[streaming-llm attention rope llm longnet deep-learning window-attention context flash-attention sliding-window transformer rotation-position-encoding register This is my reading note for Efficient Streaming Language Models with Attention Sinks. This paper proposes a method to extend a LLM to infinite length text. This method is based on sliding attention plus prepending four sink tokens to aggregate global information. This paper shares similar idea as Vision Transformers Need Registers, which adds addition token to capture global information in attention.

Introduction

Deploying Large Language Models (LLMs) in streaming applications such as multi-round dialogue, where long interactions are expected, is urgently needed but poses two major challenges. Firstly, during the decoding stage, caching previous tokens’ Key and Value states (KV) consumes extensive memory. Secondly, popular LLMs cannot generalize to longer texts than the training sequence length. Window attention, where only the most recent KVs are cached, is a natural approach — but we show that it fails when the text length surpasses the cache size. We observe an interesting phenomenon, namely attention sink, that keeping the KV of initial tokens will largely recover the performance of window attention. (p. 1)

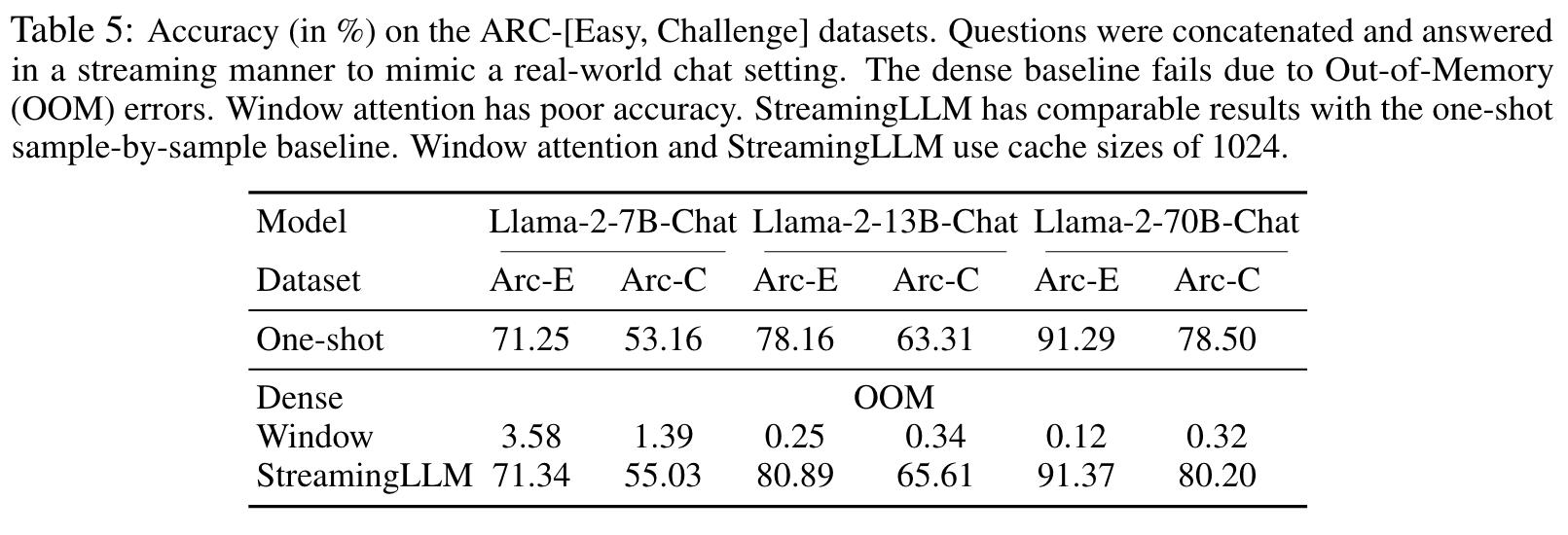

We introduce StreamingLLM, an efficient framework that enables LLMs trained with a finite length attention window to generalize to infinite sequence length without any fine-tuning. (p. 1)

The reason is that LLMs are constrained by the attention window during pre-training. Despite substantial efforts to expand this window size (Chen et al., 2023; kaiokendev, 2023; Peng et al., 2023) and improve training (Dao et al., 2022; Dao, 2023) and inference (Pope et al., 2022; Xiao et al., 2023; Anagnostidis et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023b) efficiency for lengthy inputs, the acceptable sequence length remains intrinsically finite, which doesn’t allow persistent deployments. (p. 1)

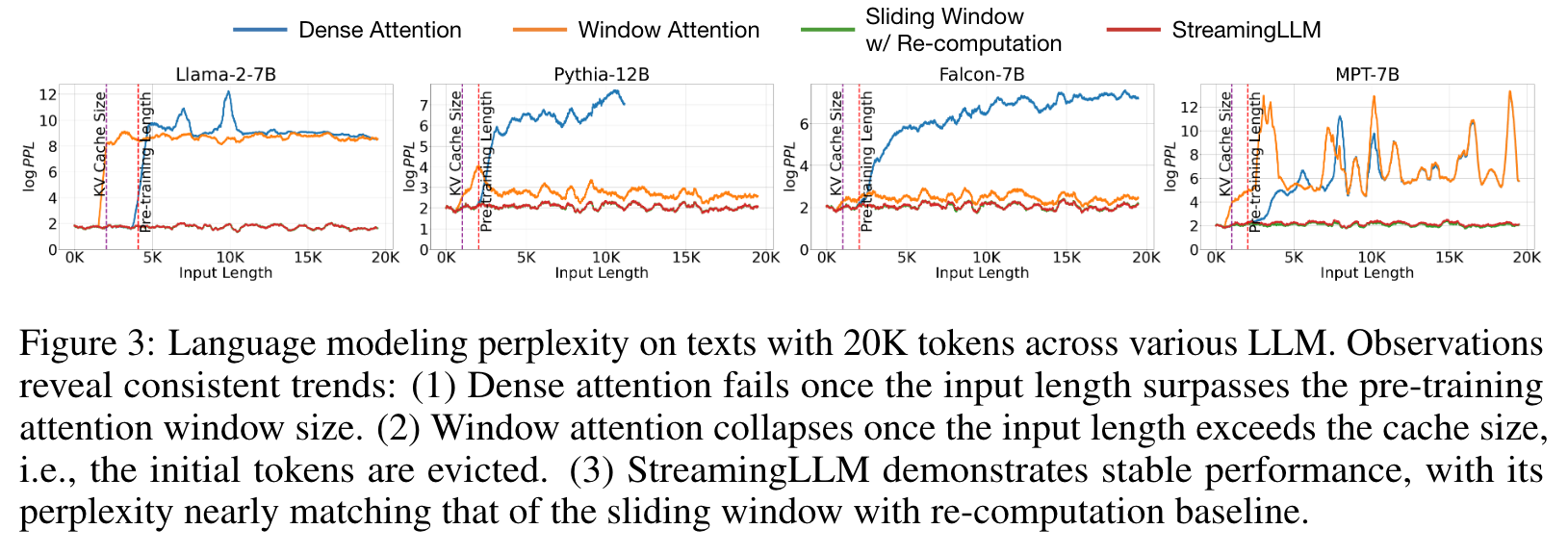

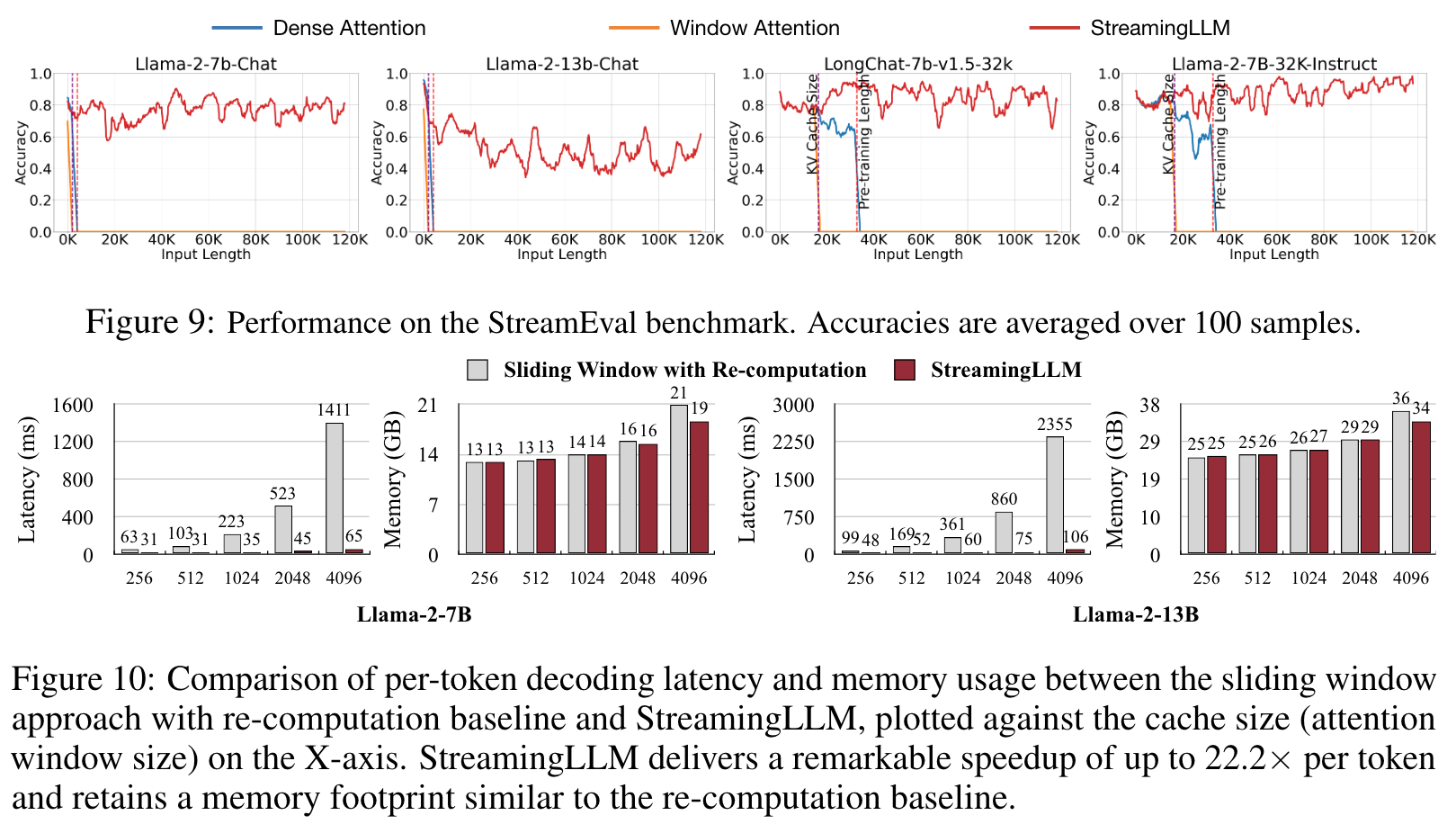

An intuitive approach, known as window attention (Beltagy et al., 2020) (Figure 1 b), maintains only a fixed-size sliding window on the KV states of most recent tokens. Although it ensures constant memory usage and decoding speed after the cache is initially filled, the model collapses once the sequence length exceeds the cache size, i.e., even just evicting the KV of the first token, as illustrated in Figure 3. Another strategy is the sliding window with re-computation (shown in Figure 1 c), which rebuilds the KV states of recent tokens for each generated token. While it offers strong performance, this approach is significantly slower due to the computation of quadratic attention within its window, making this method impractical for real-world streaming applications. (p. 2)

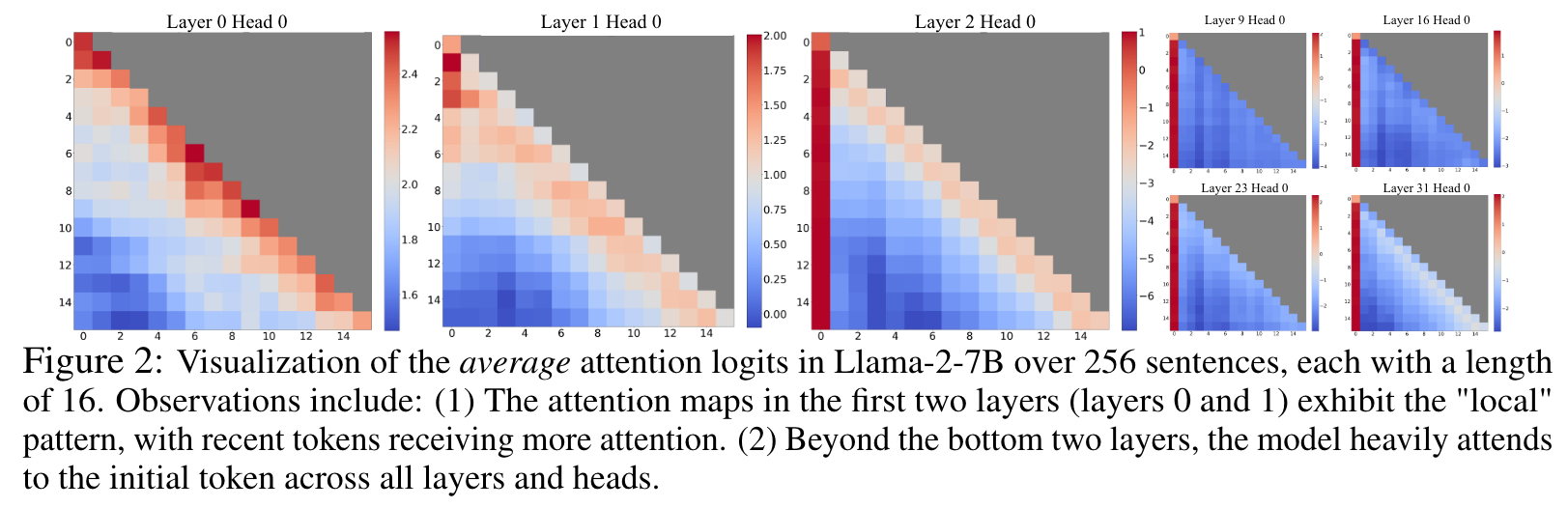

To understand the failure of window attention, we find an interesting phenomenon of autoregressive LLMs: a surprisingly large amount of attention score is allocated to the initial tokens, irrespective of their relevance to the language modeling task, as visualized in Figure 2. We term these tokens “attention sinks”. Despite their lack of semantic significance, they collect significant attention scores. We attribute the reason to the Softmax operation, which requires attention scores to sum up to one for all contextual tokens. Thus, even when the current query does not have a strong match in many previous tokens, the model still needs to allocate these unneeded attention values somewhere so it sums up to one. The reason behind initial tokens as sink tokens is intuitive: initial tokens are visible to almost all subsequent tokens because of the autoregressive language modeling nature, making them more readily trained to serve as attention sinks. (p. 2)

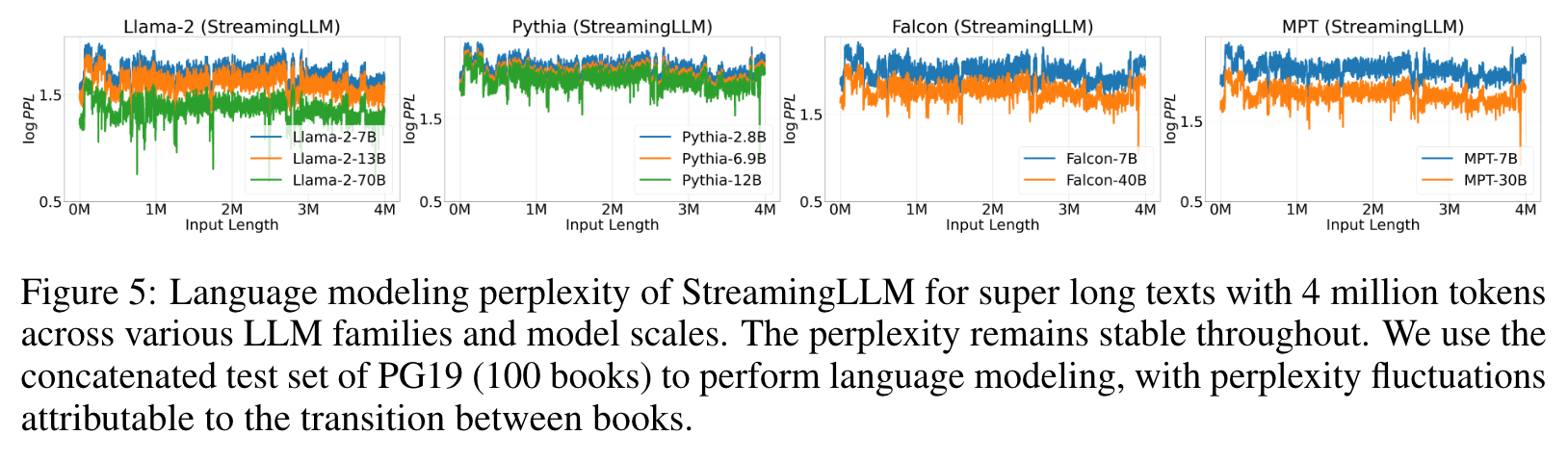

Therefore, StreamingLLM simply keeps the attention sink tokens’ KV (with just 4 initial tokens sufficing) together with the sliding window’s KV to anchor the attention computation and stabilize the model’s performance. It can reliably model 4 million tokens, and potentially even more. Compared with the only viable baseline, sliding window with recomputation, StreamingLLM achieves up to 22.2× speedup, realizing the streaming use of LLMs (p. 3)

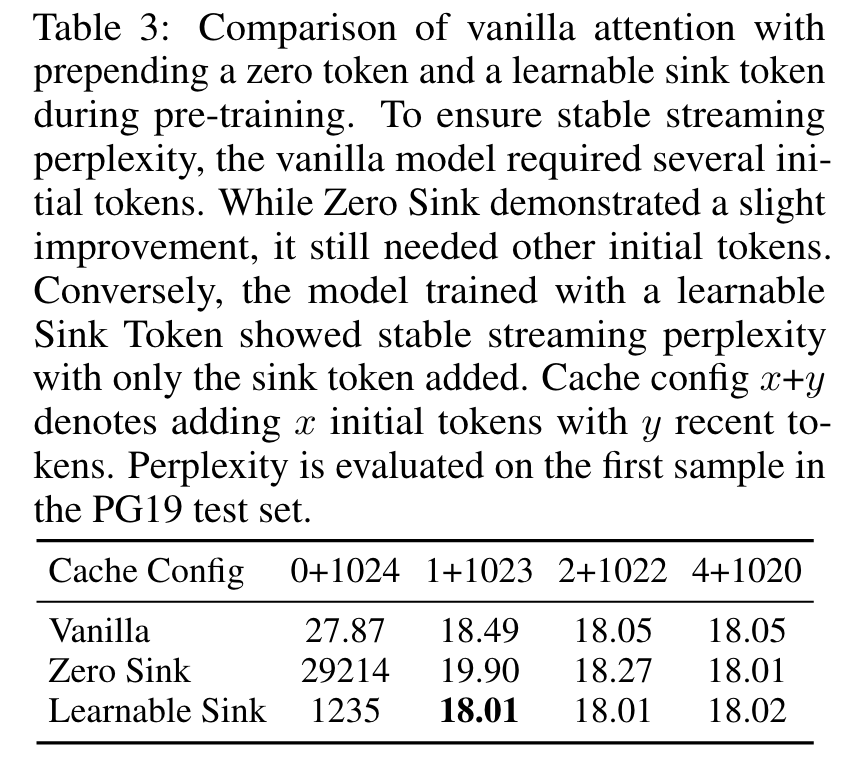

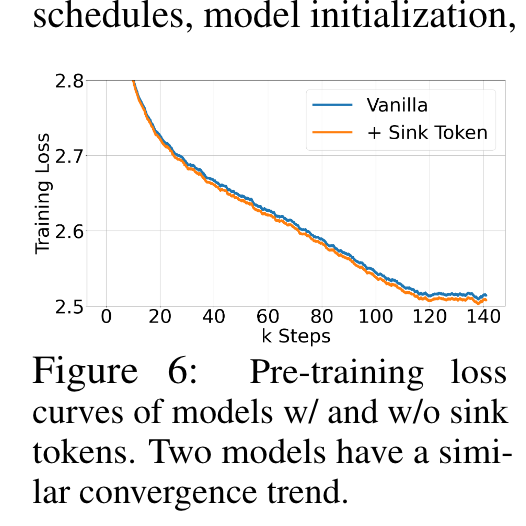

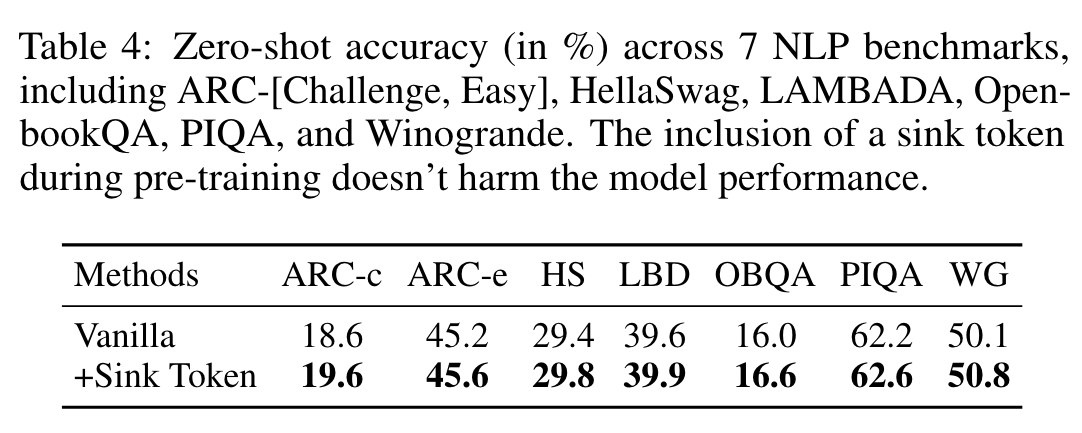

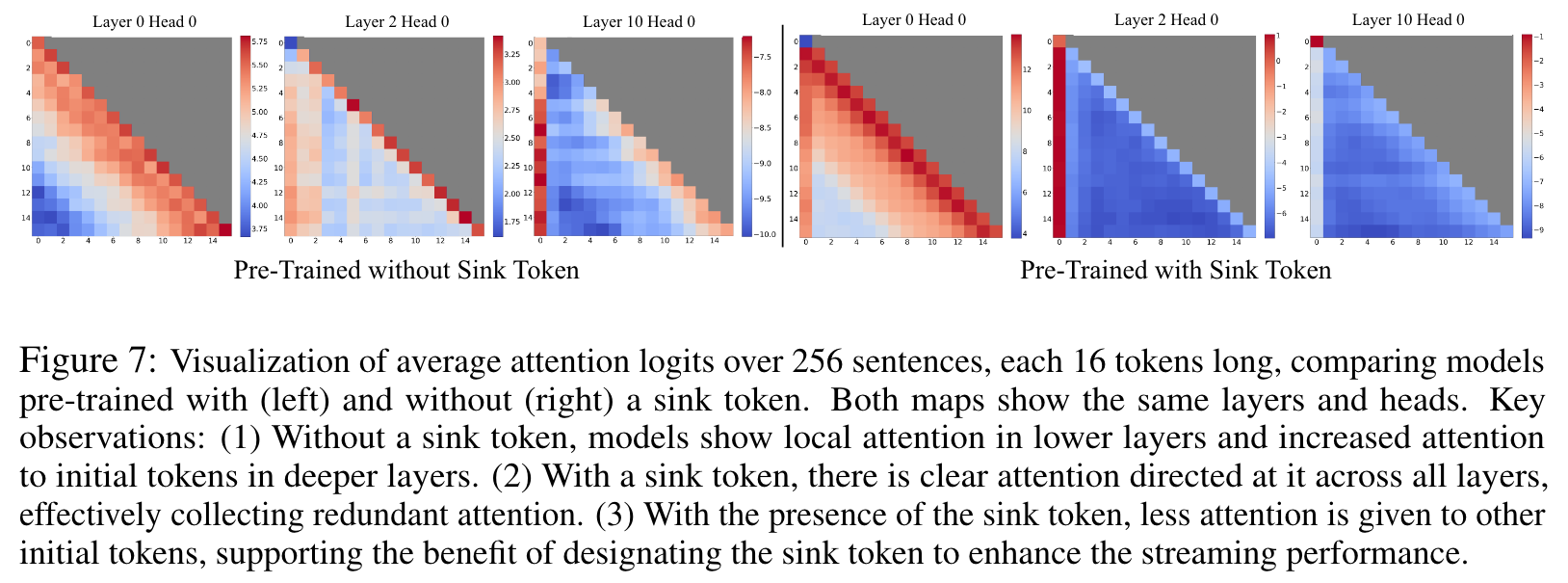

Finally, we confirm our attention sink hypothesis and demonstrate that language models can be pre-trained to require only a single attention sink token for streaming deployment. Specifically, we suggest that an extra learnable token at the beginning of all training samples can serve as a designated attention sink. (p. 3)

Related Work

Extensive research has been done on applying LLMs to lengthy texts, with three main areas of focus: Length Extrapolation, Context Window Extension, and Improving LLMs’ Utilization of Long Text. Our StreamingLLM framework primarily lies in the first category, where LLMs are applied to text significantly exceeding the pre-training window size, potentially even of infinite length. We do not expand the attention window size of LLMs or enhance the model’s memory and usage on long texts. The last two categories are orthogonal to our focus and could be integrated with our techniques. (p. 3)

Length extrapolation

It aims to enable language models trained on shorter texts to handle longer ones during testing. A predominant avenue of research targets the development of relative position encoding methods for Transformer models, enabling them to function beyond their training window. One such initiative is Rotary Position Embeddings (RoPE) (Su et al., 2021), which transforms the queries and keys in every attention layer for relative position integration. Despite its promise, subsequent research (Press et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023) indicated its underperformance on text that exceeds the training window. Another approach, ALiBi (Press et al., 2022), biases the query-key attention scores based on their distance, thereby introducing relative positional information. While this exhibited improved extrapolation, our tests on MPT models highlighted a breakdown when the text length was vastly greater than the training length. (p. 3)

Context Window Extension

It centers on expanding the LLMs’ context window, enabling the processing of more tokens in one forward pass. A primary line of work addresses the training efficiency problem Solutions have ranged from system-focused optimizations like FlashAttention (Dao et al., 2022; Dao, 2023), which accelerates attention computation and reduces memory footprint, to approximate attention methods (Zaheer et al., 2020; Beltagy et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Kitaev et al., 2020) that trade model quality for efficiency. Recently, there has been a surge of work on extending pre-trained LLMs with RoPE (Chen et al., 2023; kaiokendev, 2023; bloc97, 2023; Peng et al., 2023), involving position interpolation and fine-tuning. However, all the aforementioned techniques only extend LLMs’ context window to a limited extent, which falls short of our paper’s primary concern of handling limitless inputs. (p. 3)

Improving LLMs’ Utilization of Long Text

It optimizes LLMs to better capture and employ the content within the context rather than merely taking them as inputs (p. 3)

Proposed Method

THE FAILURE OF WINDOW ATTENTION AND ATTENTION SINKS

While the window attention technique offers efficiency during inference, it results in an exceedingly high language modeling perplexity (p. 4)

Identifying the Point of Perplexity Surge

Figure 3 shows the perplexity of language modeling on a 20K token text. It is evident that perplexity spikes when the text length surpasses the cache size, led by the exclusion of initial tokens. This suggests that the initial tokens, regardless of their distance from the tokens being predicted, are crucial for maintaining the stability of LLMs. (p. 4)

Why do LLMs break when removing initial tokens’ KV?

We find that, beyond the bottom two layers, the model consistently focuses on the initial tokens across all layers and heads. The implication is clear: removing these initial tokens’ KV will remove a considerable portion of the denominator in the SoftMax function (Equation 1) in attention computation. This alteration leads to a significant shift in the distribution of attention scores away from what would be expected in normal inference settings (p. 4)

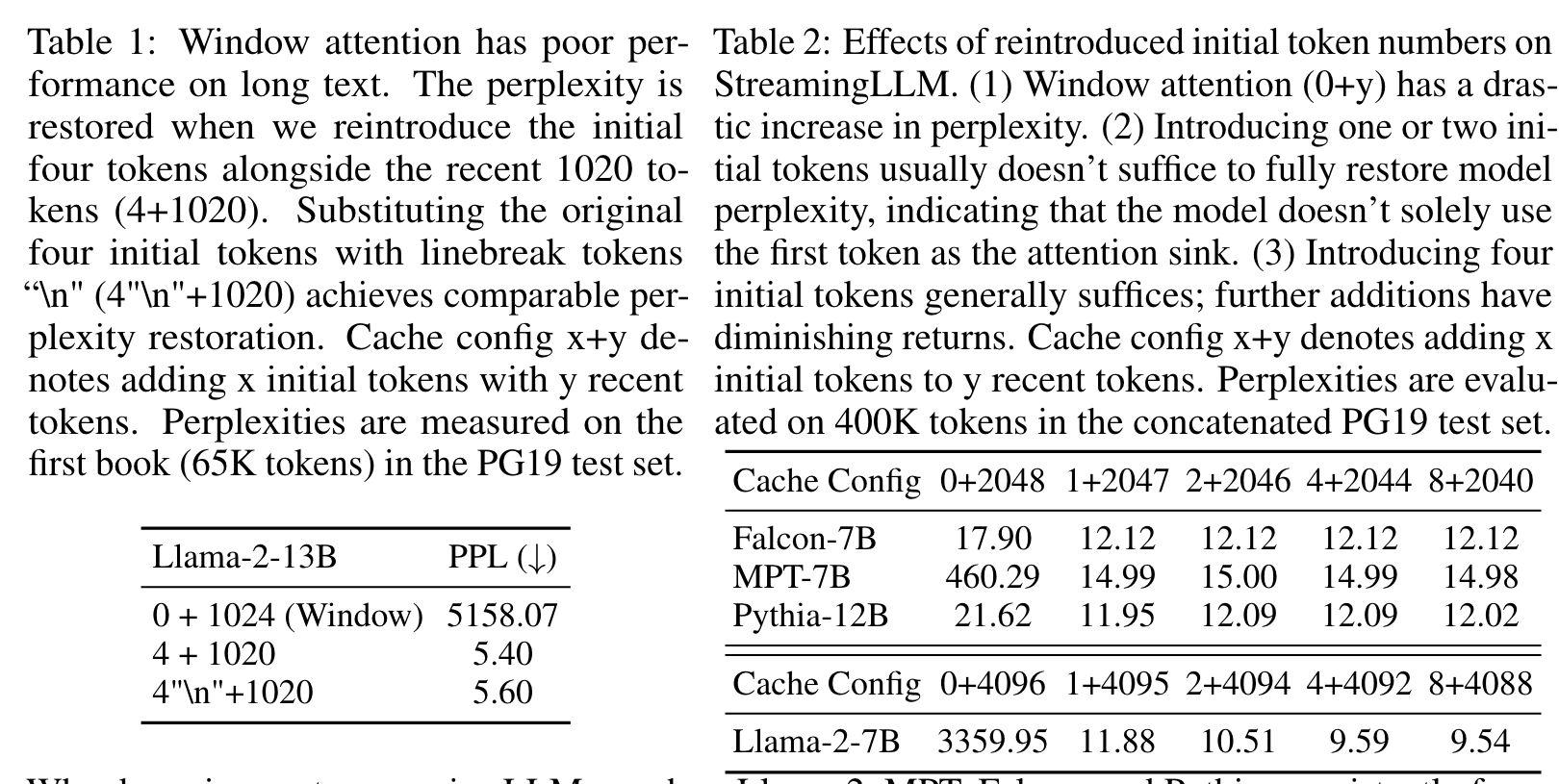

There are two possible explanations for the importance of the initial tokens in language modeling: (1) Either their semantics are crucial, or (2) the model learns a bias towards their absolute position. To distinguish between these possibilities, we conduct experiments (Table 1), wherein the first four tokens are substituted with the linebreak token “\n”. The observations indicate that the model still significantly emphasizes these initial linebreak tokens. Furthermore, reintroducing them restores the language modeling perplexity to levels comparable to having the original initial tokens. This suggests that the absolute position of the starting tokens, rather than their semantic value, holds greater significance. (p. 4)

LLMs attend to Initial Tokens as Attention Sinks

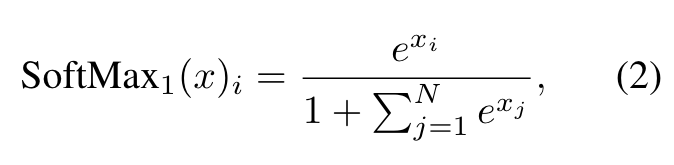

The nature of the SoftMax function (Equation 1) prevents all attended tokens from having zero values. This requires aggregating some information from other tokens across all heads in all layers, even if the current embedding has sufficient self-contained information for its prediction. Consequently, the model tends to dump unnecessary attention values to specific tokens. (p. 4)

Our explanation is straightforward: Due to the sequential nature of autoregressive language modeling, initial tokens are visible to all subsequent tokens, while later tokens are only visible to a limited set of subsequent tokens. As a result, initial tokens are more easily trained to serve as attention sinks, capturing unnecessary attention. (p. 5)

We’ve noted that LLMs are typically trained to utilize multiple initial tokens as attention sinks rather than just one. As illustrated in Figure 2, the introduction of four initial tokens, as attention sinks, suffices to restore the LLM’s performance. In contrast, adding just one or two doesn’t achieve full recovery (p. 5)

This lack of a uniform starting token leads the model to use several initial tokens as attention sinks. We hypothesize that by incorporating a stable learnable token at the start of all training samples, it could singularly act as a committed attention sink, eliminating the need for multiple initial tokens to ensure consistent streaming. Token 13 Generating Token 14 0 1 2 3 10 11 12 13 14 (p. 5)

ROLLING KV CACHE WITH ATTENTION SINKS

Alongside the current sliding window tokens, we reintroduce a few starting tokens’ KV in the attention computation. The KV cache in StreamingLLM can be conceptually divided into two parts, as illustrated in Figure 4: (1) Attention sinks (four initial tokens) stabilize the attention computation; 2) Rolling KV Cache retains the most recent tokens, crucial for language modeling. (p. 5)

When determining the relative distance and adding positional information to tokens, StreamingLLM focuses on positions within the cache rather than those in the original text. This distinction is crucial for StreamingLLM’s performance. (p. 5)

For encoding like RoPE, we cache the Keys of tokens prior to introducing the rotary transformation. Then, we apply position transformation to the keys in the rolling cache at each decoding phase. On the other hand, integrating with ALiBi is more direct. Here, the contiguous linear bias is applied instead of a ’jumping’ bias to the attention scores. This method of assigning positional embedding within the cache is crucial to StreamingLLM’s functionality, ensuring that the model operates efficiently even beyond its pre-training attention window size. (p. 5)

Due to this, the model inadvertently designates globally visible tokens, primarily the initial ones, as attention sinks. A potential remedy can be the intentional inclusion of a global trainable attention sink token, denoted as a “Sink Token”, which would serve as a repository for unnecessary attention scores. Alternatively, replacing the conventional SoftMax function with a variant like SoftMax-off-by-One (Miller, 2023), (p. 6)

Note that this SoftMax alternative is equivalent to using a token with an all-zero Key and Value features in the attention computation. We denote this method as “Zero Sink” to fit it consistently in our framework. (p. 6)

Experiment

ABLATION STUDIES

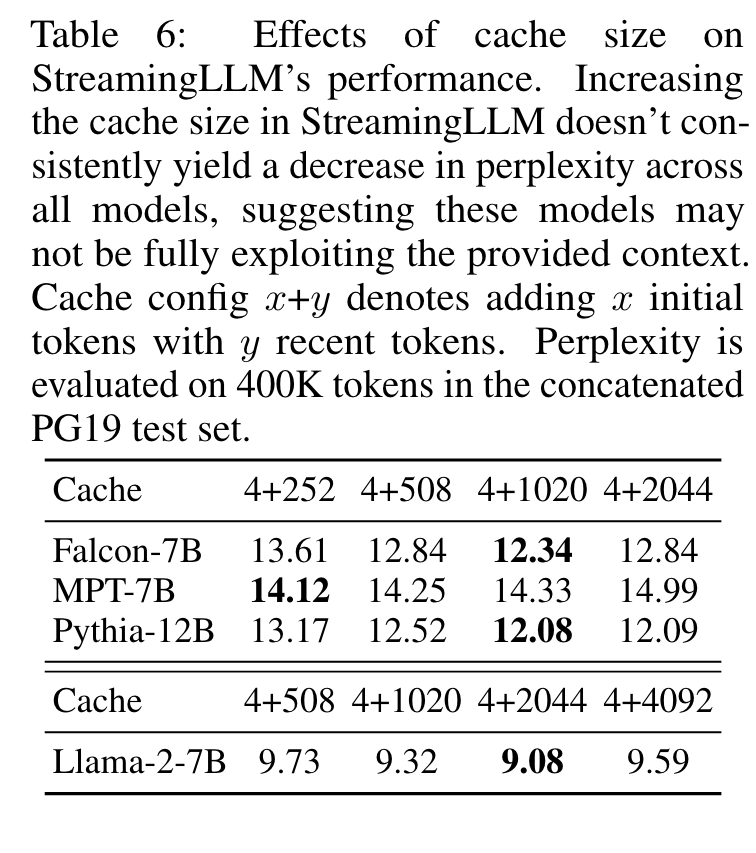

Numbers of Initial Tokens

The results show the insufficiency of introducing merely one or two initial tokens, whereas a threshold of four initial tokens appears enough, with subsequent additions contributing marginal effects. This result justifies our choice of introducing 4 initial tokens as attention sinks in StreamingLLM. (p. 8)

Cache Sizes

This inconsistency shows a potential limitation where these models might not maximize the utility of the entire context they receive. (p. 9)