SeamlessM4T-Massively Multilingual & Multimodal Machine Translation

[multimodal w2v-bert response-ai review quantization segmentation asr voice-activity-detection text2speech seamlessm4t hubert whisper llm language-identification machine-translation speech-recognition audio self_supervised sonar bert tts nllb read transformer vad laser This is my reading note 1/2 on SeamlessM4T-Massively Multilingual & Multimodal Machine Translation. It is end to end multi language translation system supports multimodality (text and audio). This paper also provides a good review on machine translation. This note focus on data preparation part of the paper and please read SeamlessM4T-model for the other part.

Introduction

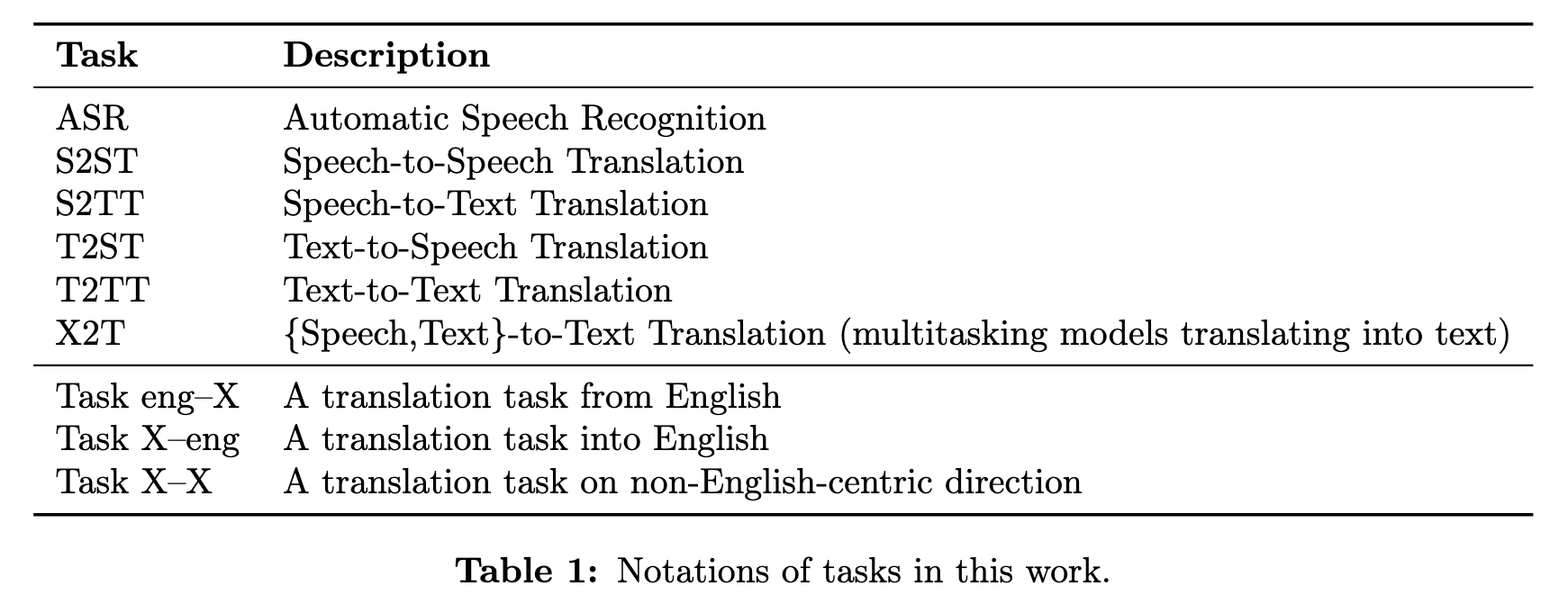

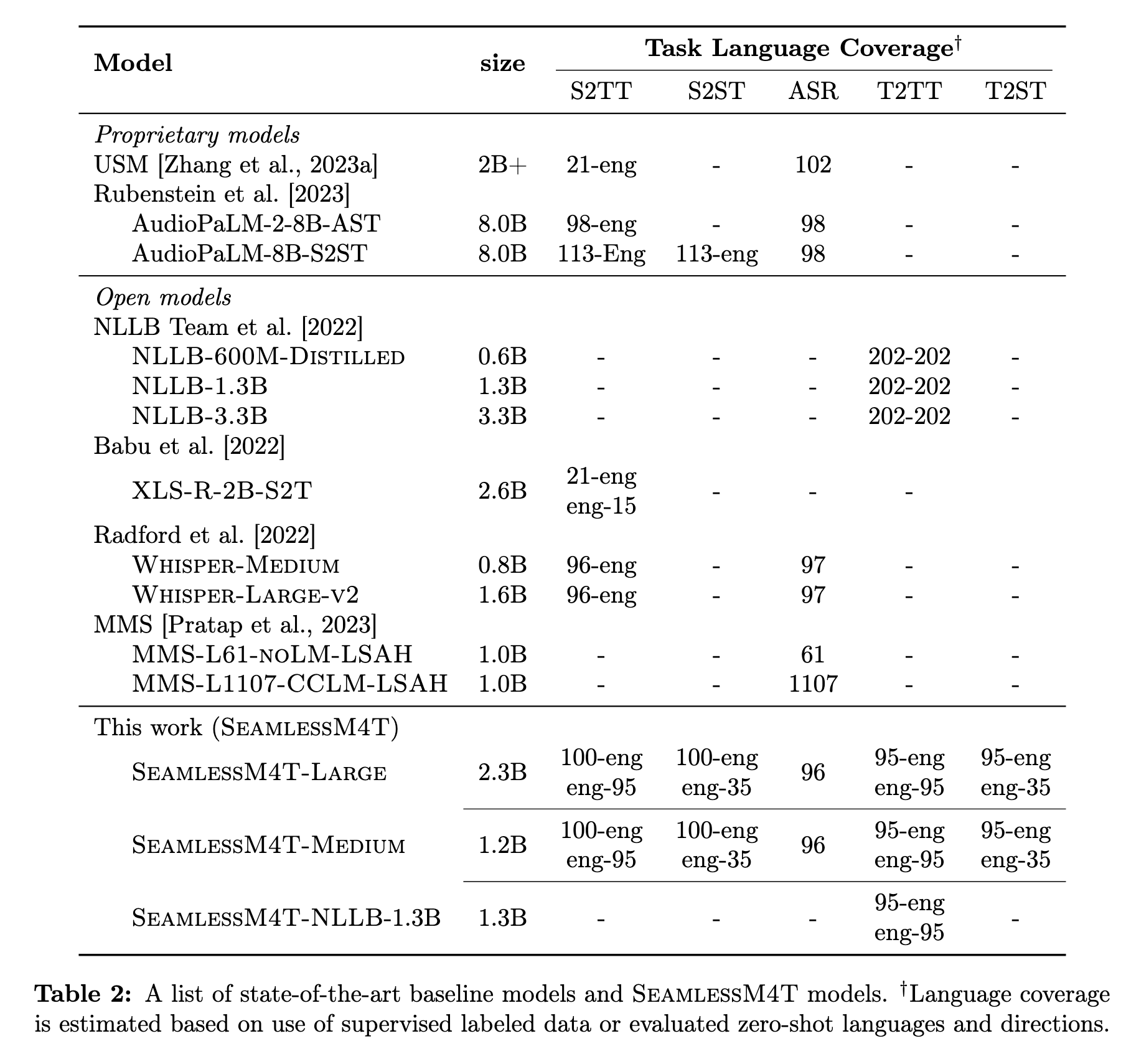

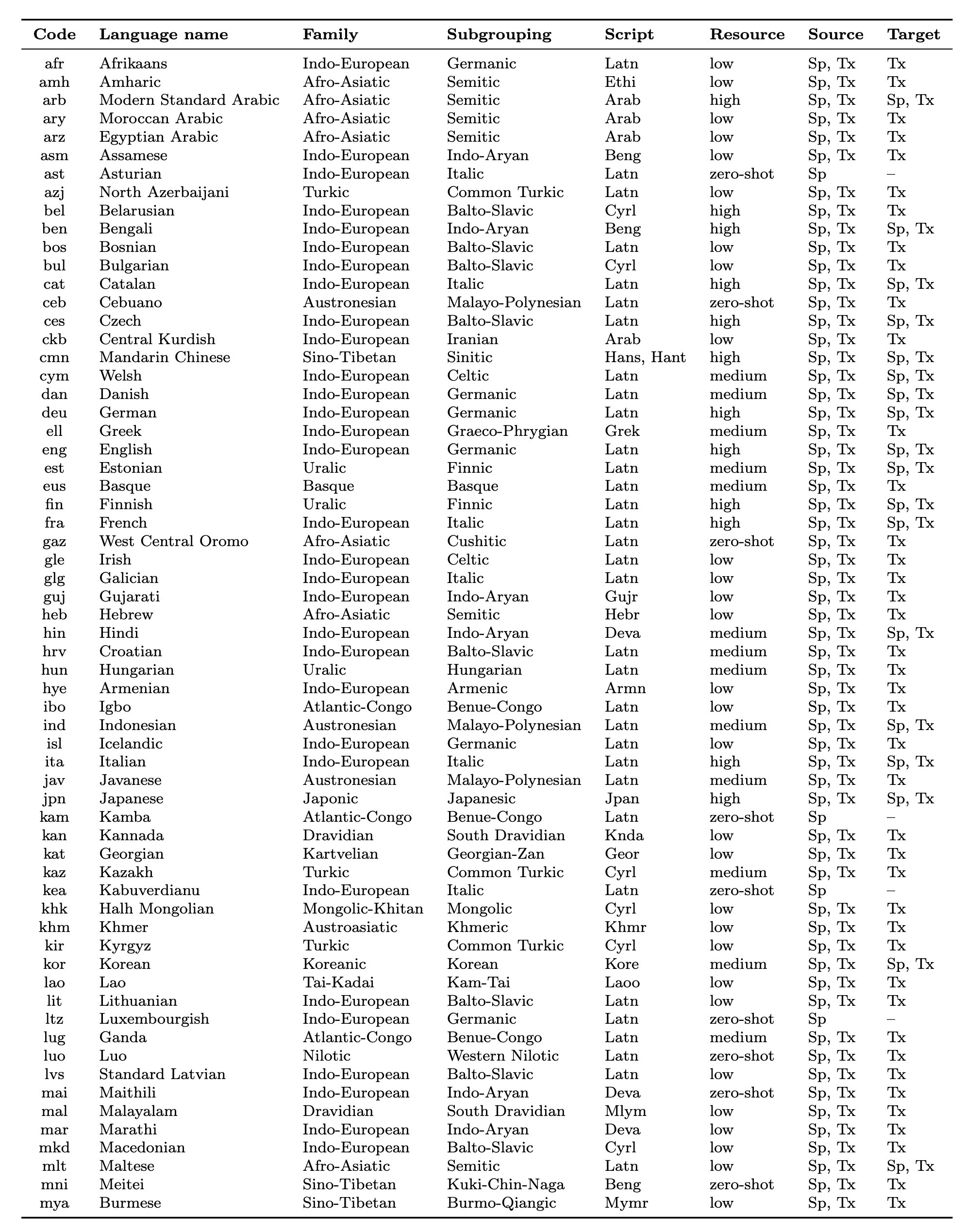

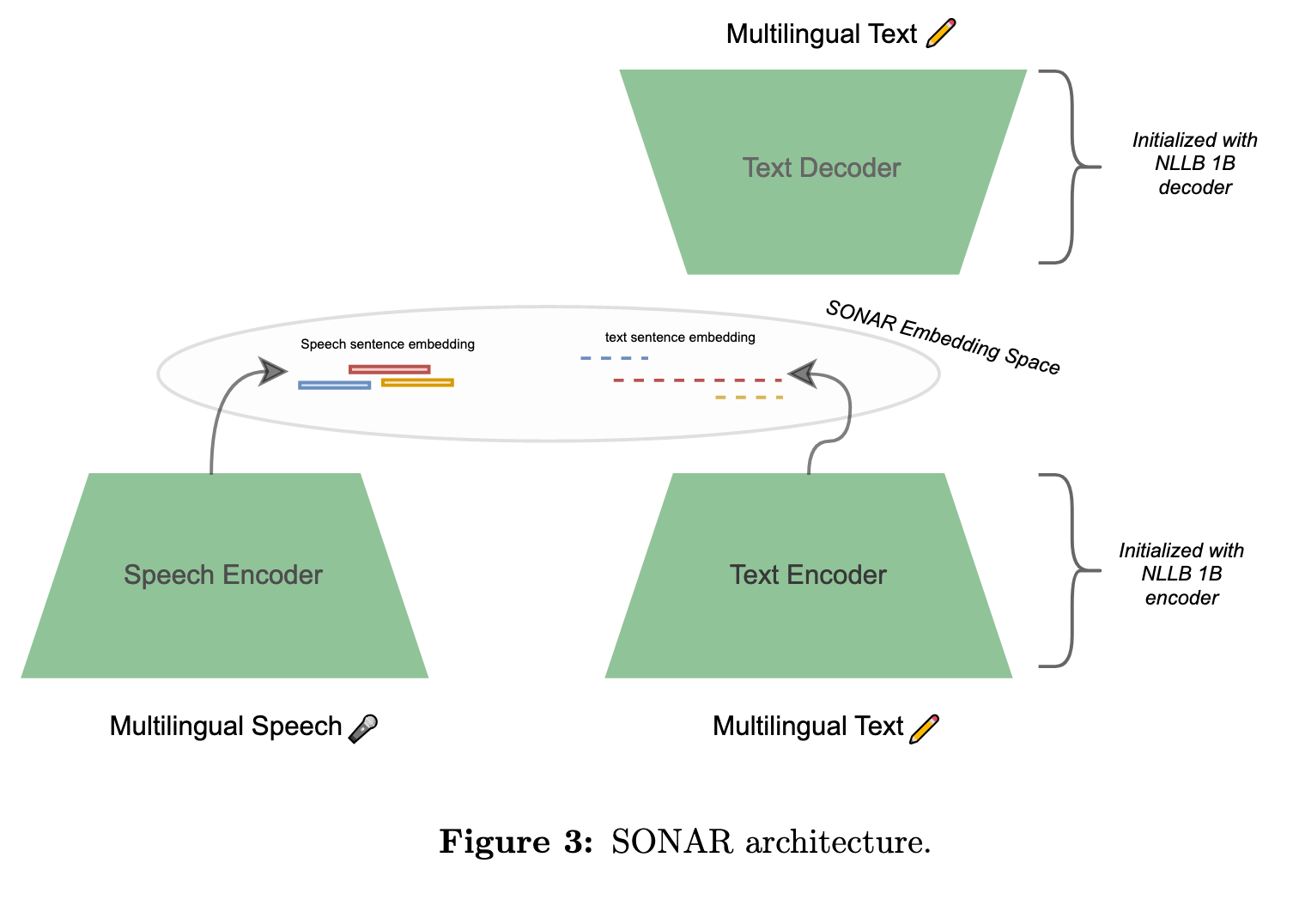

More specifically, conventional speech-to-speech translation systems rely on cascaded systems composed of multiple subsystems performing translation progressively, putting scalable and high-performing unified speech translation systems out of reach. To address these gaps, we introduce SeamlessM4T—Massively Multilingual & Multimodal Machine Translation—a single model that supports speech- to-speech translation, speech-to-text translation, text-to-speech translation, text-to-text translation, and automatic speech recognition for up to 100 languages. To build this, we used 1 million hours of open speech audio data to learn self-supervised speech representations with w2v-BERT 2.0. Subsequently, we created a multimodal corpus of automatically aligned speech translations, dubbed SeamlessAlign. Filtered and combined with human- labeled and pseudo-labeled data (totaling 406,000 hours), we developed the first multilingual system capable of translating from and into English for both speech and text. (p. 1)

Today, existing systems of such kind suffer from three main shortcomings. One, they tend to focus on high-resource languages such as English, Spanish, and French, leaving many low-resource languages behind. Two, they mostly service translations from a source language into English (X–eng) and not vice versa (eng–X). Three, most S2ST systems today rely heavily on cascaded systems composed of multiple subsystems that perform translation progressively—e.g., from automatic speech recognition (ASR) to T2TT, and subsequently text-to-speech (TTS) synthesis in a 3-stage system. Attempts to unify these multiple capabilities under one singular entity have led to early iterations of end-to-end speech translation systems [Lavie et al., 1997; Jia et al., 2019b; Lee et al., 2022a]. However, these systems do not match the performance of their cascaded counterparts [Agarwal et al., 2023], which are more equipped to leverage large-scale multilingual components (e.g., NLLB for T2TT or Whisper for ASR [Radford et al., 2022]) and unsupervised or weakly-supervised data. (p. 4)

Although Translatotron relied on S2TT as an auxiliary task during training, the target spectrograms were directly generated at inference time. Translatotron-2, on the other hand, relies on the intermediate decoding outputs of phonemes. Concurrently with Translatotron, Tjandra et al. [2019] proposed S2ST models based on discrete speech representations that do not require text transcriptions in training. These discrete representations or units are learned through unsupervised term discovery and a sequence-to-sequence model trained to translate units from one language to another. Relatedly, Lee et al. [2022a] uses HuBERT [Hsu et al., 2021], a pre-trained speech representation model, to encode speech and learn target-side discrete units. S2ST is, thus, decomposed into speech-to-unit (S2U) and subsequently unit-to-speech with a speech re-synthesizer [Polyak et al., 2021]. (p. 10)

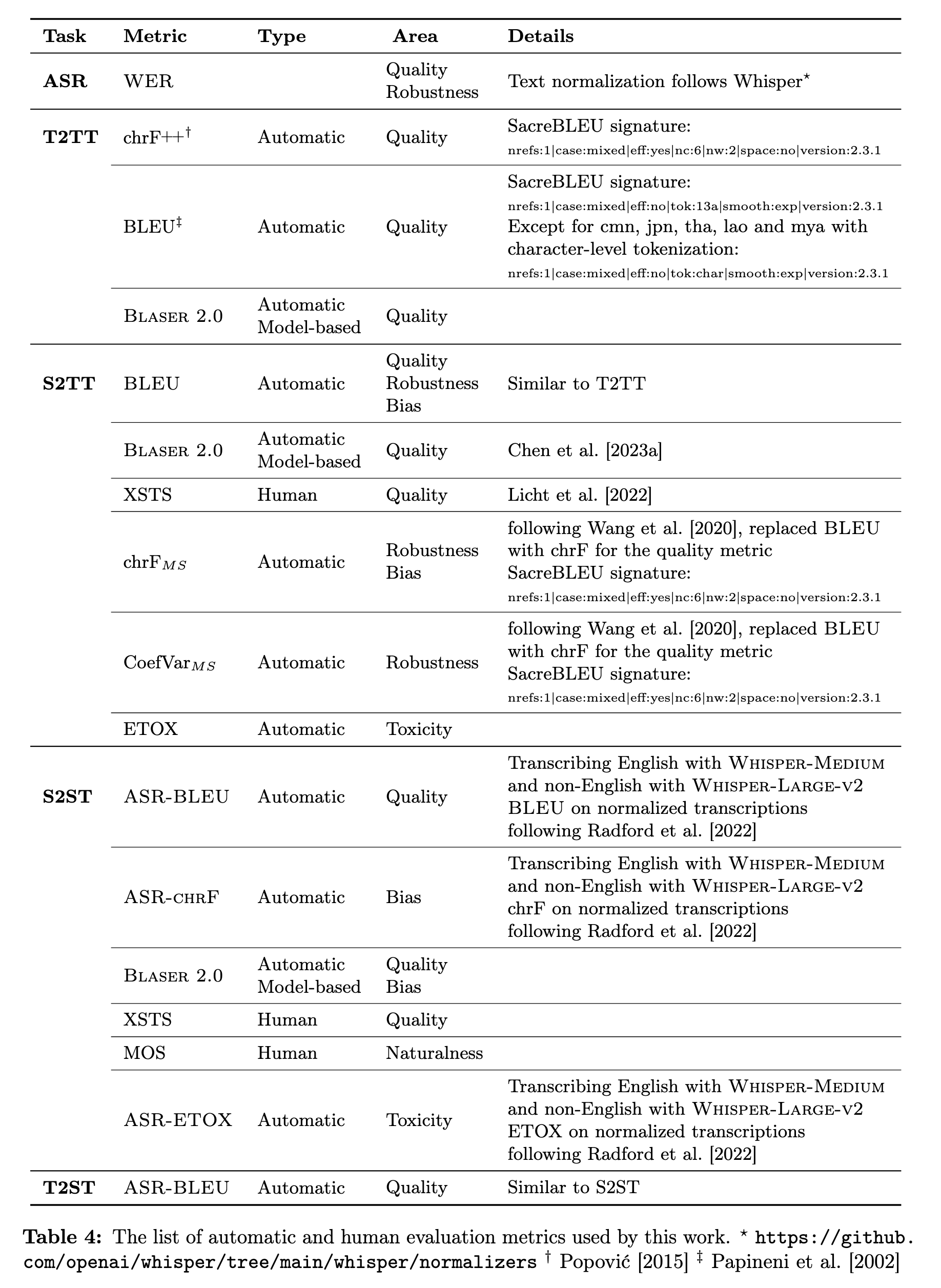

Throughout this paper, we primarily evaluated our models on the following datasets:

- Flores-200 [NLLB Team et al., 2022]: a many-to-many multilingual translation benchmark dataset for 200 languages (we evaluated on devtest).

- Fleurs [Conneau et al., 2022]: an n-way parallel speech and text dataset in 102 languages built on the text translation Flores-101 benchmark [Goyal et al., 2022]. Fleurs is well suited for several downstream tasks involving speech and text. We evaluated on the test set, except in ablation experiments where we evaluated on the dev set.

- CoVoST 2 [Wang et al., 2021c]: a large-scale multilingual S2TT corpus covering translations from 21 languages into English and from English into 15 languages. We evaluated on the test set.

- CVSS [Jia et al., 2022b]: a multilingual-to-English speech-to-speech translation (S2ST) corpus, covering sentence-level parallel S2ST pairs from 21 languages into English. We evaluated text-based semantic accuracy on CVSS-C for the tasks of S2ST and T2ST. We note that some samples from the evaluation data were missing (in 8 out of 21 languages: Catalan, German, Estonian, French, Italian, Mongolian, Persian, and Portuguese). (p. 11)

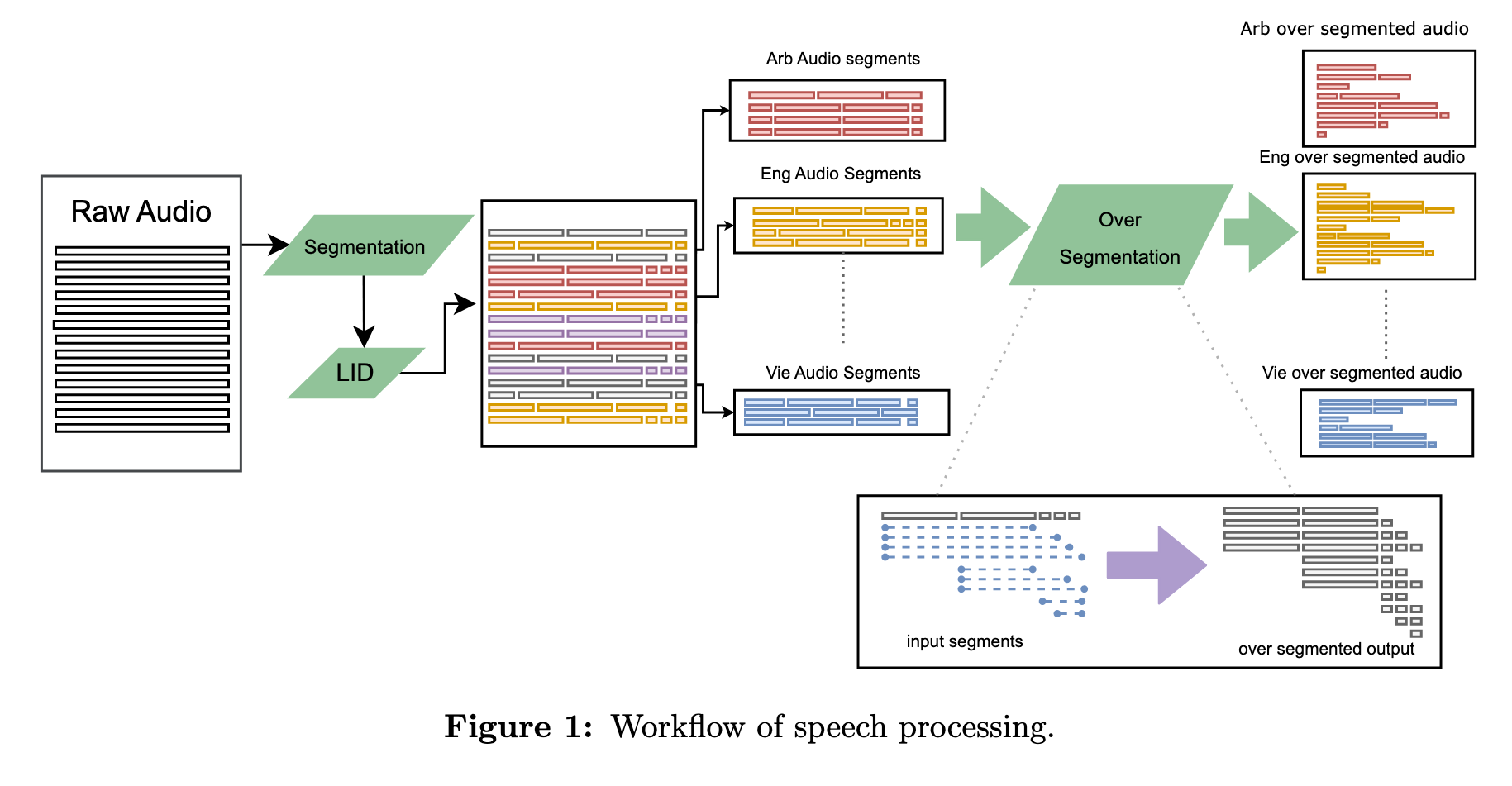

SeamlessAlign: Automatically Creating Aligned Data for Speech

Parallel data mining emerges as an alternative to using closed data, both in terms of language coverage and corpus size. The dominant approach today is to encode sentences from various languages and modalities into a joint fixed-size embedding space and to find parallel instances based on a similarity metric. Mining is then performed by pairwise comparison over massive monolingual corpora, where sentences with similarity above a certain threshold are considered mutual translations [Schwenk, 2018; Artetxe and Schwenk, 2019a]. This approach was first introduced using the multilingual Laser space [Artetxe and Schwenk, 2019b]. Teacher-student training was then used to scale this approach to 200 languages [Heffernan et al., 2022; NLLB Team et al., 2022] and subsequently, the speech modality [Duquenne et al., 2021, 2023a]. (p. 16)

Speech-language identification

While numerous off-the-shelf LID models exist, none could cover our target list of 100 languages.4 Therefore, we trained our own model, following the ECAPA-TDNN architec- ture introduced in [Desplanques et al., 2020] (p. 17)

| We thus estimated the Gaussian distribution of the LID scores per language for correct and incorrect classifications on the development corpus. We selected a threshold per language such that p(correct | score) > p(incorrect | score). By rejecting 8% of the data, we were able to further increase the F1 measure by almost 3%. (p. 18) |

Gathering raw audio and text data at scale

Subsequently, we filtered out the non-speech data with a bespoke audio event detection (AED) model. (p. 19)

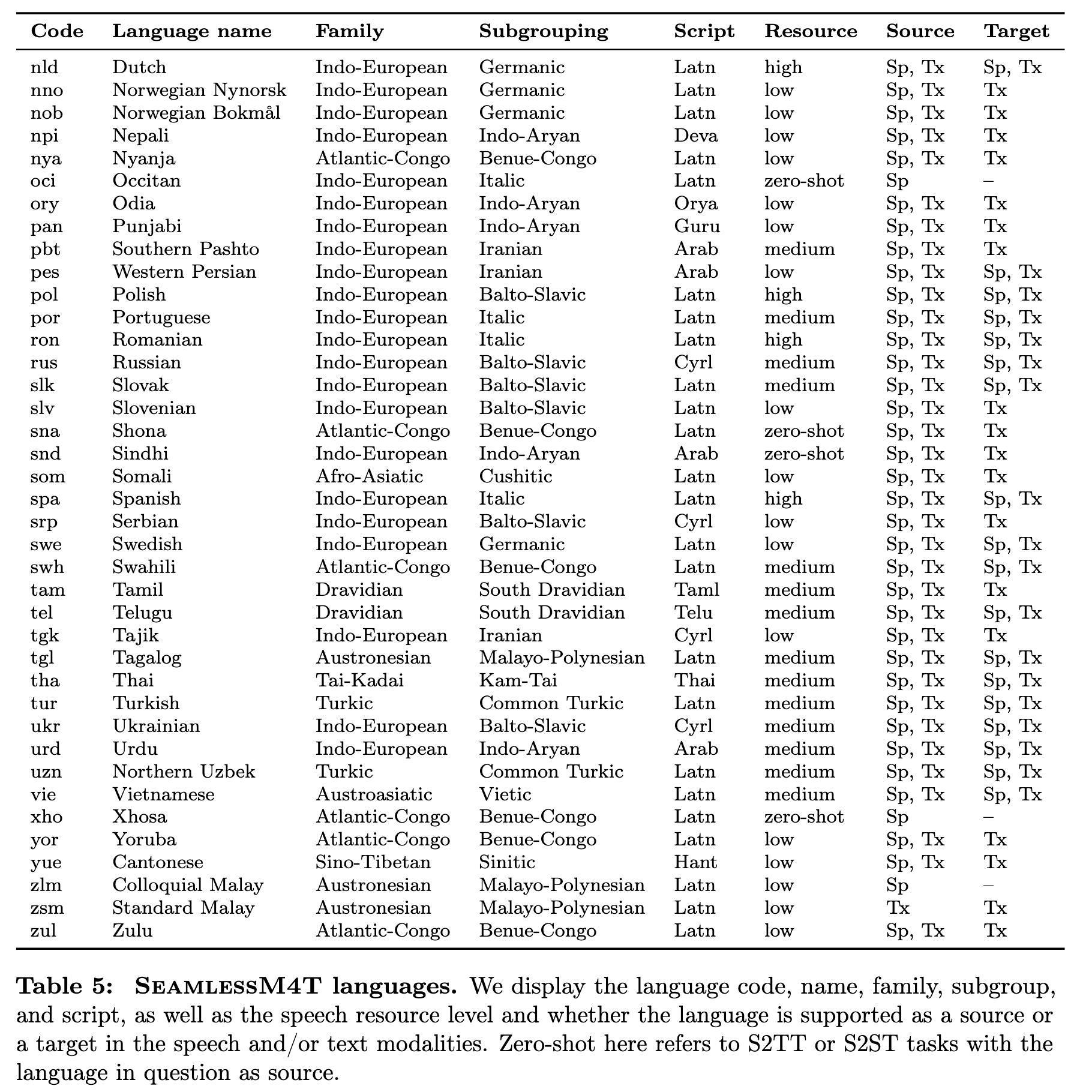

To perform S2TT or S2ST mining, it is desirable to split audio files into smaller chunks that map as closely as possible to self-contained sentences, equivalent to sentences in a text corpus. However, genuine semantic segmentation in speech is an open-ended problem–pauses can be an integral part of a message and can naturally occur differently across languages. For mining purposes, it is impossible to prejudge what specific segments can maximize the overall quality of the mined pairs.

We thus followed the over-segmentation approach drawn from [Duquenne et al., 2021] (as depicted in Figure 1). First, we used an open Voice Activity Detection (VAD) model [Silero, 2021] to split audio files into shorter segments. Subsequently, our speech LID model was used on each file. Finally, we created several possible overlapping splits of each segment and left the choice of the optimal split to the mining algorithm described in the next section. (p. 19)

Speech mining

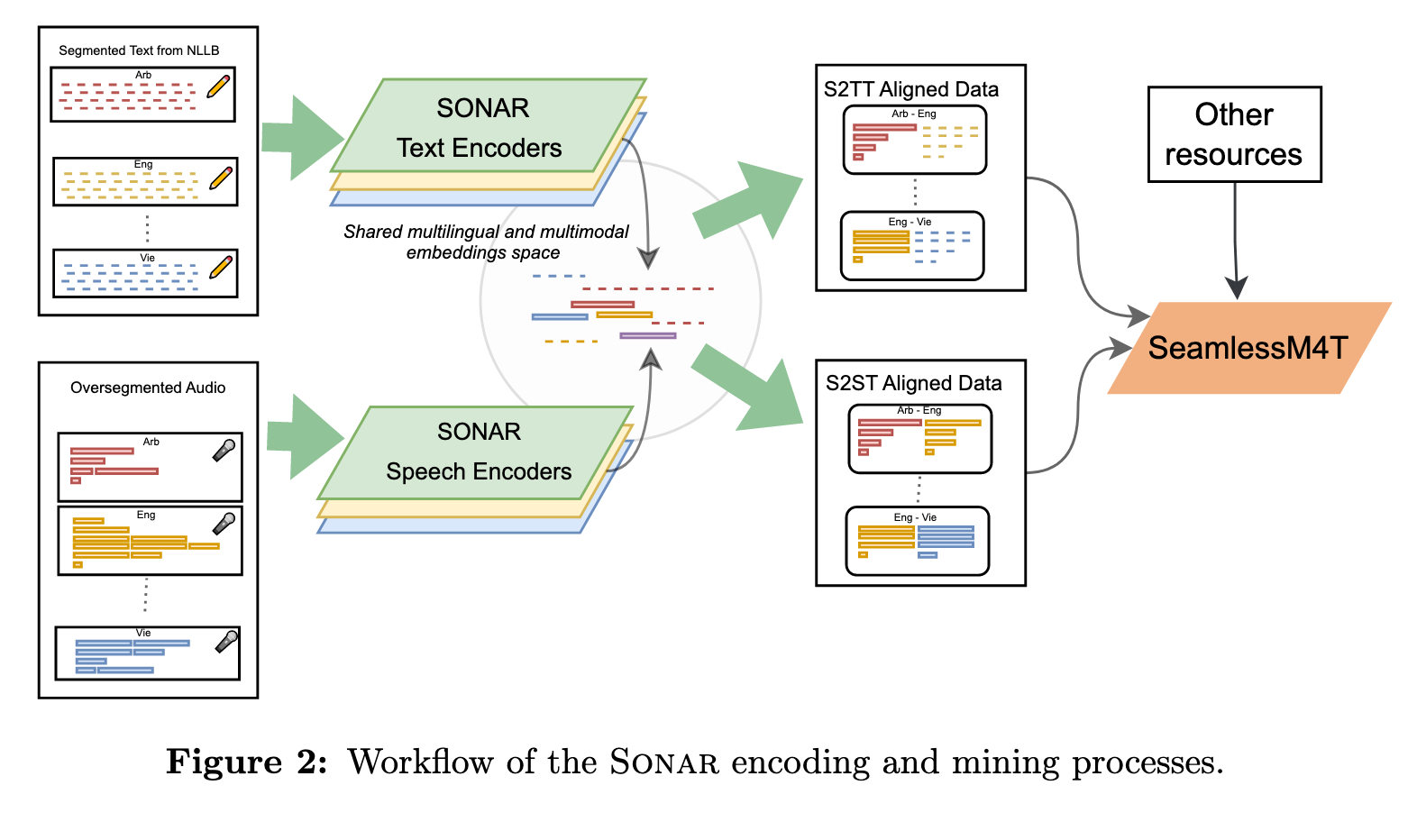

As a second step and following [Duquenne et al., 2021], the new Sonar text embedding space is extended to the speech modality through teacher-student training. In that work, a fixed-size speech representation was obtained by taking the BOS output of a pretrained XLS-R model [Babu et al., 2022]. This model was then fine-tuned to maximize the cosine loss between this pooled speech representation and sentence embeddings in the same languages (ASR transcriptions) or in English (speech translations) (p. 21)

- Attention-pooling. Instead of the usual pooling methods (i.e., mean or max-pooling), we implemented a 3-layer sequence-to-sequence model to convert the variable length sequence of w2v-BERT 2.0 to a fixed size vector, (p. 21)

- Following [Heffernan et al., 2022; NLLB Team et al., 2022], we grouped languages by linguistic families (i.e., Germanic or Indian languages) and trained them together in one speech encoder. (p. 21)

We performed so-called global mining, where all speech segments in one language are compared to all speech segments in another language. Local mining, on the contrary, would try to leverage knowledge on longer speech chunks that are likely to contain many parallel segments. A typical example would be documentation on an international event in multiple languages. Such high-level information is very difficult to obtain at scale. (p. 23)

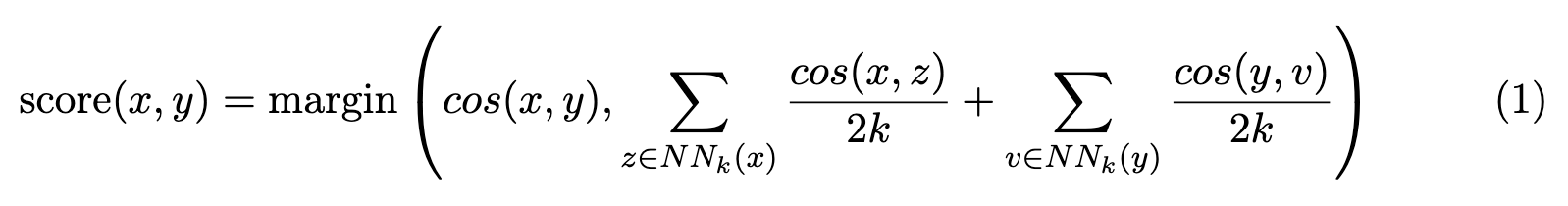

First, the embeddings for all speech segments and text sentences are calculated. These are then indexed with the FAISS library [Johnson et al., 2019], enabling efficient large-scale similarity search on GPUs. Finally, nearest neighbors to all elements in both directions are retrieved, and margin scores are computed following the formula introduced in [Artetxe and Schwenk, 2019a]: (p. 23)

where x and y are the source and target sentences, and NNk(x) denotes the k nearest neighbors of x in the other language. We set k to 16. (p. 23)

Related Work

Speech LID

Spoken language identification has been traditionally approached in a two-stage workflow: a classifier is trained on top of conventional representations like the i-vector or x-vector, extracted from the raw audio signal (p. 24)

Recent initiatives aimed at increasing language coverage to go beyond a handful of conventionally very high-resource languages. The ECAPA-TDNN architecture introduced in [Desplanques et al., 2020] has proven effective to distinguish between the 107 languages of Voxlingua107 [Valk and Alumäe, 2021]. The XLS-R pretrained model [Babu et al., 2022] is also fine-tuned on a language identification task using the same dataset. Whisper-Large- v2 is another popular model that can perform this task for 99 languages [Radford et al., 2022]. Very recently, the MMS project further broadened language support to 4,000 spoken languages [Pratap et al., 2023]. (p. 25)

Speech segmentation

To achieve sentence-like speech segments, a commonly employed method is pause-based segmentation using Voice Activity Detection (VAD) (p. 25)

Pause-based segments may not align with semantically coherent sentences; in fact, they tend to be too short because speaker pauses can extend beyond sentence boundaries. (p. 25)

Multilingual and multimodal representations

Another direction of research is to first train an English sentence representation (e.g., sentence-BERT [Reimers and Gurevych, 2019]) and in a second step, extend it to more languages using teacher-student training (p. 25)

There are several works that indirectly create speech-to-speech corpora. One direction of research is to perform speech synthesis on corpora aligned at the text level, (p. 26)