Aligning Large Multimodal Models with Factually Augmented RLHF

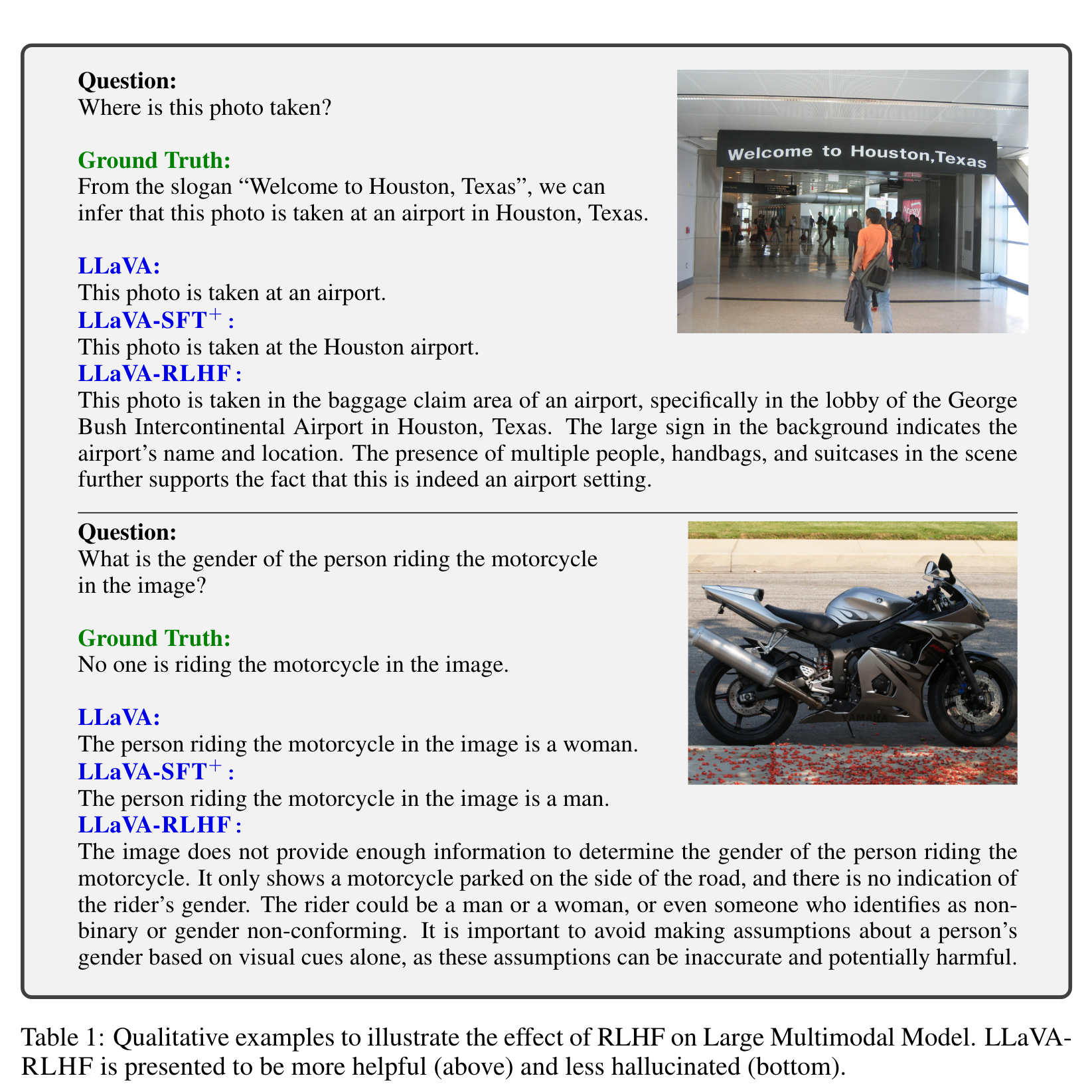

[reinforcement flamingo hallucination kosmos shikra multimodal llm vqa reinforcement-learning-human-feedback deep-learning otter instruct-blip llava mini-gpt rlhf This is my reading note for Aligning Large Multimodal Models with Factually Augmented RLHF. This paper discusses how to mitigate hallucination for large multimodal model.it proposes two methods, 1) add additional human labeled data to train a reward model to guide the fine tune of the final model: 2) add additional factual data to the reward model besides model’s response.

Introduction

Large Multimodal Models (LMM) are built across modalities and the misalignment between two modalities can result in “hallucination”, generating textual outputs that are not grounded by the multimodal information in context (p. 1)

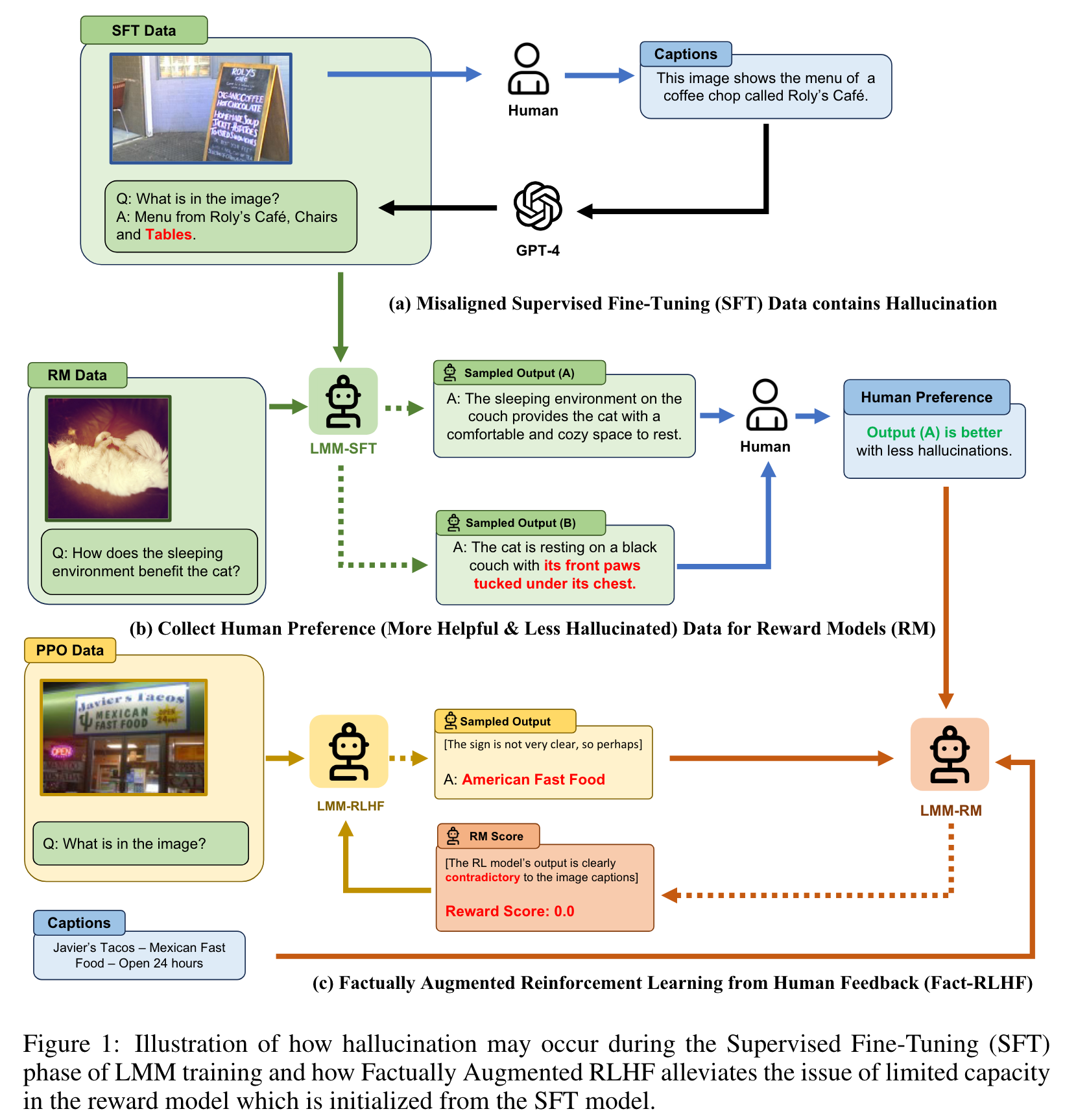

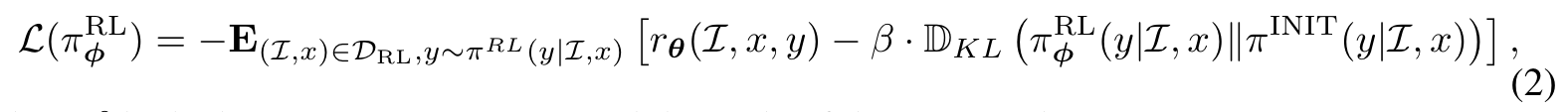

Human annotators are asked to compare two responses and pinpoint the more hallucinated one, and the vision-language model is trained to maximize the simulated human rewards. We propose a new alignment algorithm called Factually Augmented RLHF that augments the reward model with additional factual information such as image captions and ground-truth multi-choice options, which alleviates the reward hacking phenomenon in RLHF and further improves the performance. (p. 1)

Yet, developing LMMs faces challenges, notably the gap between the volume and quality of multimodal data versus text-only datasets. Such limitations in data can lead to misalignment between the vision and language modalities. Consequently, LMMs may produce hallucinated outputs, which are not accurately anchored to the context provided by images (p. 1)

To mitigate the challenges posed by the scarcity of high-quality visual instruction tuning data for LMM training, we introduce LLaVA-RLHF, a vision-language model trained for improved multimodal alignment. One of our key contributions is the adaptation of the Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) (Stiennon et al., 2020; Ouyang et al., 2022; Bai et al., 2022a), a general and scalable alignment paradigm that shows great success for text-based AI agents, to the multimodal alignment for LMMs. By collecting human preferences with an emphasis on detecting hallucinations1, and utilizes those preferences in reinforcement learning for LMM fine-tuning (Ziegler et al., 2019; Stiennon et al., 2020). This approach can improve the multimodal alignment with a relatively low annotation cost, e.g., collecting 10K human preferences for image-based conversations with $3000. To the best of our knowledge, this approach is the first successful adaptation of RLHF to multimodal alignment (p. 2)

A potential issue with the current RLHF paradigm is called reward hacking, which means achieving high scores from the reward model does not necessarily lead to improvement in human judgments. To prevent reward hacking, previous work (Bai et al., 2022a; Touvron et al., 2023b) proposed to iteratively collect “fresh” human feedback, which tends to be costly and cannot effectively utilize existing human preference data. In this work, we propose a more data-efficient alternative, i.e., we try to make the reward model capable of leveraging existing human-annotated data and knowledge in larger language models. Firstly, we improve the general capabilities of the reward model by using a better vision encoder with higher resolutions and a larger language model. Secondly, we introduce a novel algorithm named Factually Augmented RLHF (Fact-RLHF), which calibrates the reward signals by augmenting them with additional information such as image captions or ground-truth multi-choice option, as illustrated in Fig. 1. (p. 2)

Specifically, we convert VQA-v2 (Goyal et al., 2017a) and A-OKVQA (Schwenk et al., 2022) into a multi-round QA task, and Flickr30k (Young et al., 2014b) into a Spotting Captioning task (Chen et al., 2023a), and train the LLaVA-SFT+ models based on the new mixture of data. (p. 3)

Related Work

Hallucination Prior to the advent of LLMs, the NLP community primarily defined “hallucination” as the generation of nonsensical content or content that deviates from its source (Ji et al., 2023). The introduction of versatile LLMs has expanded this definition, as outlined by (Zhang et al., 2023) into: 1) Input-conflicting hallucination, which veers away from user-given input, exemplified in machine translation (Lee et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2020); 2) Context-conflicting hallucination where output contradicts prior LLM-generated information (Shi et al., 2023); and 3) Fact-conflicting hallucination, where content misaligns with established knowledge (Lin et al., 2021). (p. 11)

METHOD

MULTIMODAL RLHF

The basic pipeline of our multimodal RLHF can be summarized into three stages:

- Multimodal Supervised Fine-Tuning A vision encoder and a pre-trained LLM are jointly finetuned on an instruction-following demonstration dataset using token-level supervision to produce a supervised fine-tuned (SFT) model πSFT. (p. 4)

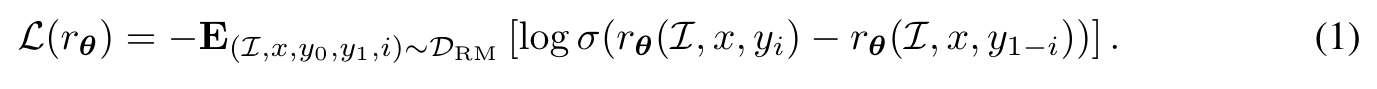

- Multimodal Preference Modeling In this stage, a reward model, alternatively referred to as a preference model, is trained to give a higher score to the “better” response. The pairwise comparison training data are typically annotated by human annotators. (p. 4)

- Reinforcement Learning Here, a policy model, initialized through multimodal supervised finetuning (SFT) (Ouyang et al., 2022; Touvron et al., 2023b), is trained to generate an appropriate response for each user query by maximizing the reward signal as provided by the reward model. To address potential over-optimization challenges, notably reward hacking, a per-token KL penalty derived from the initial policy model (Ouyang et al., 2022) is sometimes applied. (p. 4)

Recent studies (Zhou et al., 2023; Touvron et al., 2023b) show that high-quality instruction tuning data is essential for aligning Large Language Models (LLMs). We find this becomes even more salient for LMMs. (p. 5)

In this work, we consider enhancing LLaVA (98k conversations, after holding out 60k conversations for preference modeling and RL training) with high-quality instruction-tuning data derived from existing human annotations. Specifically, we curated three categories of visual instruction data: “Yes” or “No” queries from VQA-v2 (83k) (Goyal et al., 2017b), multiple-choice questions from A-OKVQA (16k) (Marino et al., 2019), and grounded captions from Flickr30k (23k) (Young et al., 2014a). Our analysis revealed that this amalgamation of datasets significantly improved LMM capabilities on benchmark tests. (p. 5)

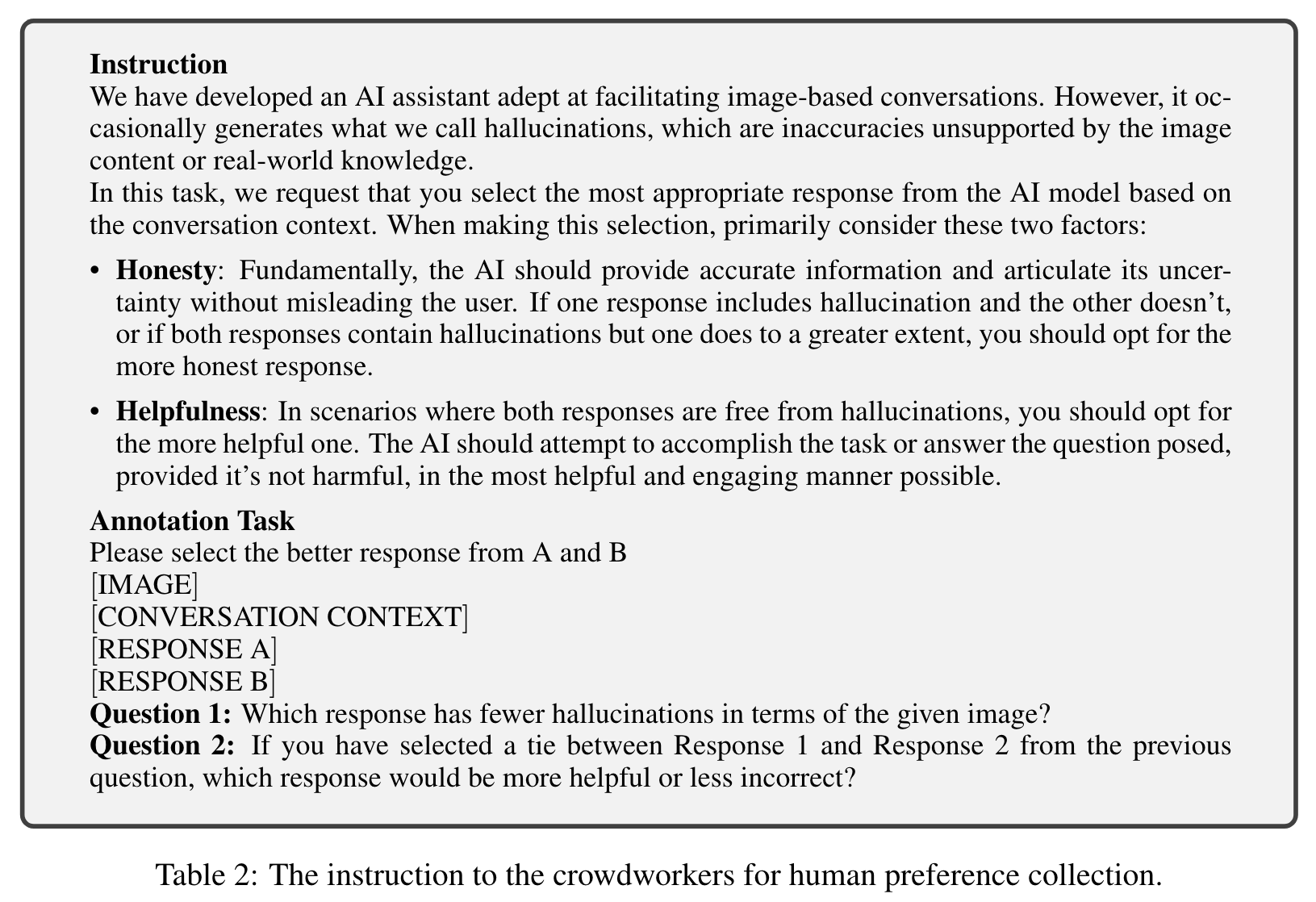

HALLUCINATION-AWARE HUMAN PREFERENCE COLLECTION

in this study, we decide to differentiate between responses that are merely less helpful and those that are inconsistent with the images (often characterized by multimodal hallucinations) (p. 5)

Nonetheless, our training process integrates a single reward model that emphasizes both multimodal alignment and overall helpfulness2. (p. 5)

FACTUALLY AUGMENTED RLHF (FACT-RLHF)

- Reward Hacking in RLHF In preliminary multimodal RLHF experiments, we observe that due to the intrinsic multimodal misalignment in the SFT model, the reward model is weak and sometimes cannot effectively detect hallucinations in the RL model’s responses. I (p. 5)

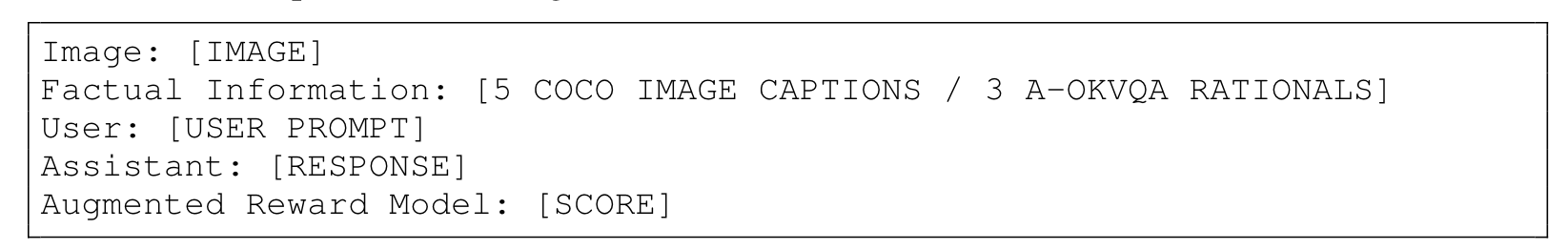

- Facutual Augmentation To augment the capability of the reward model, we propose Factually Augmented RLHF (Fact-RLHF), where the reward model has access to additional ground-truth information such as image captions to calibrate its judgment. (p. 6) In Factually Augmented RLHF (Fact-RLHF), the reward model has additional information about the textual descriptions of the image: (p. 6)

This prevents the reward model hacked by the policy model when the policy model generates some hallucinations that are clearly not grounded by the image captions. (p. 6)

The factually augmented reward model is trained on the same binary preference data as the vanilla reward model, except that the factual information is provided both during the model fine-tuning and inference. (p. 6)

This prevents the reward model hacked by the policy model when the policy model generates some hallucinations that are clearly not grounded by the image captions. (p. 6)

The factually augmented reward model is trained on the same binary preference data as the vanilla reward model, except that the factual information is provided both during the model fine-tuning and inference. (p. 6)

Furthermore, we observed that RLHF-trained models often produce more verbose outputs, a phenomenon also noted by Dubois et al. (2023). While these verbose outputs might be favored by users or by automated LLM-based evaluation systems (Sun et al., 2023b; Zheng et al., 2023), they tend to introduce more hallucinations for LMMs. In this work, we follow Sun et al. (2023a) and incorporate the response length, measured in the number of tokens, as an auxiliary penalizing factor. (p. 6)

EXPERIMENTS

- Base Model We adopt the same network architecture as LLaVA (Liu et al., 2023a). Our LLM is based on Vicuna (Touvron et al., 2023a; Chiang et al., 2023), and we utilize the pre-trained CLIP visual encoder, ViT-L/14 (Radford et al., 2021). We use grid features both before and after the final Transformer layer. To project image features to the word embedding space, we employ a linear layer. (p. 6)

- RL Models: Reward, Policy, and Value The architecture of the reward model is the same as the base LLaVA model, except that the embedding output of the last token is linearly projected to a scalar value to indicate the reward of the whole response. (p. 6)

Metric

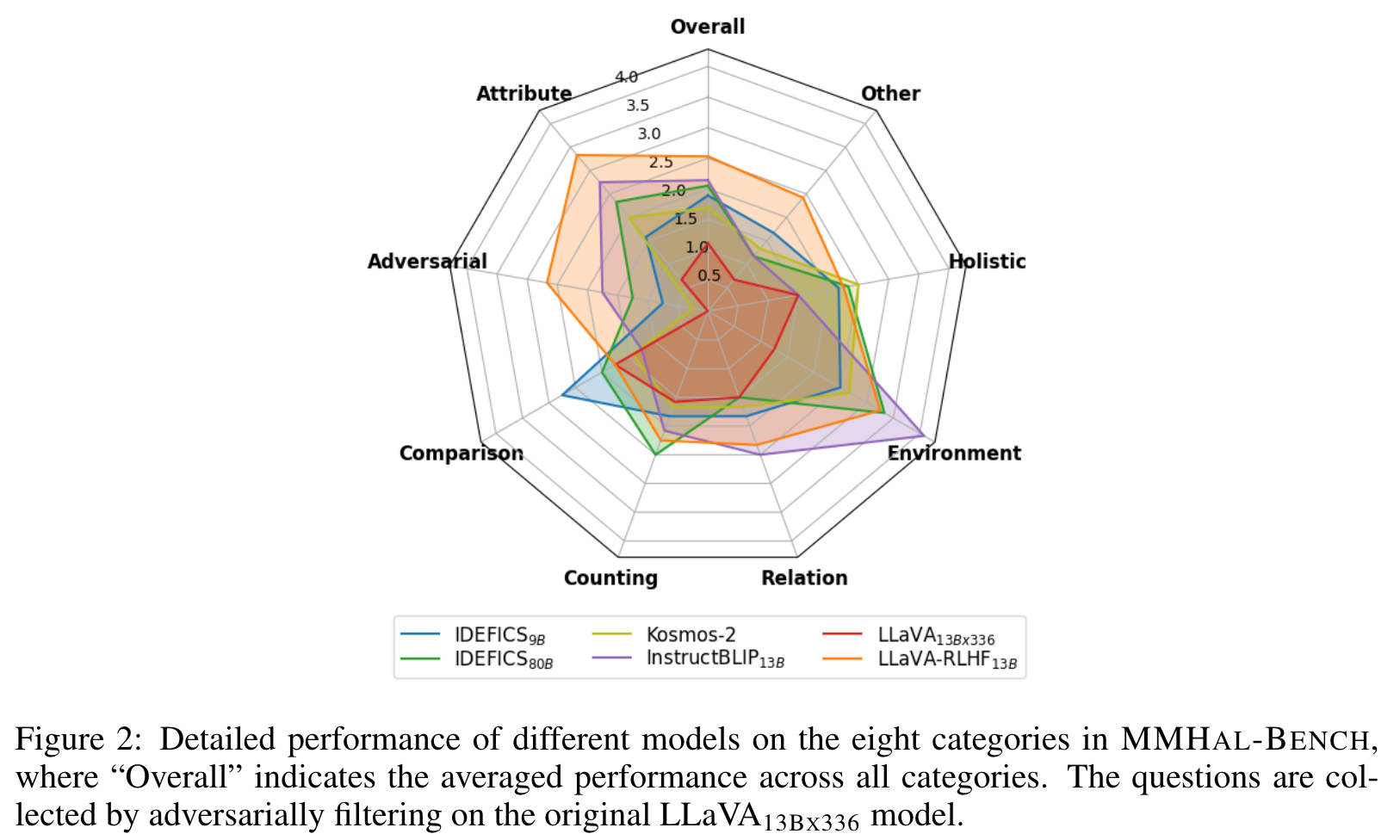

In MMHAL-BENCH, we have meticulously designed 96 image-question pairs, ranging in 8 question categories × 12 object topics. More specifically, we have observed that LMM often make false claims about the image contents when answering some types of questions, and thus design our questions according to these types:

- Object attribute: LMMs incorrectly describe the visual attributes of invididual objects, such as color and shape.

- Adversarial object: LMMs answers questions involving something that does not exist in the image, instead of pointing out that the referred object cannot be found.

- Comparison: LMMs incorrectly compare the attributes of multiple objects.

- Counting: LMMs fail to count the number of the named objects.

- Spatial relation: LMMs fail to understand the spatial relations between multiple objects in the response.

- Environment: LMMs make wrong inference about the environment of the given image.

- Holistic description: LMMs make false claims about contents in the given image when giving a comprehensive and detailed description of the whole image.

- Others: LMMs fail to recognize the text or icons, or incorrectly reason based on the observed visual information. (p. 8)

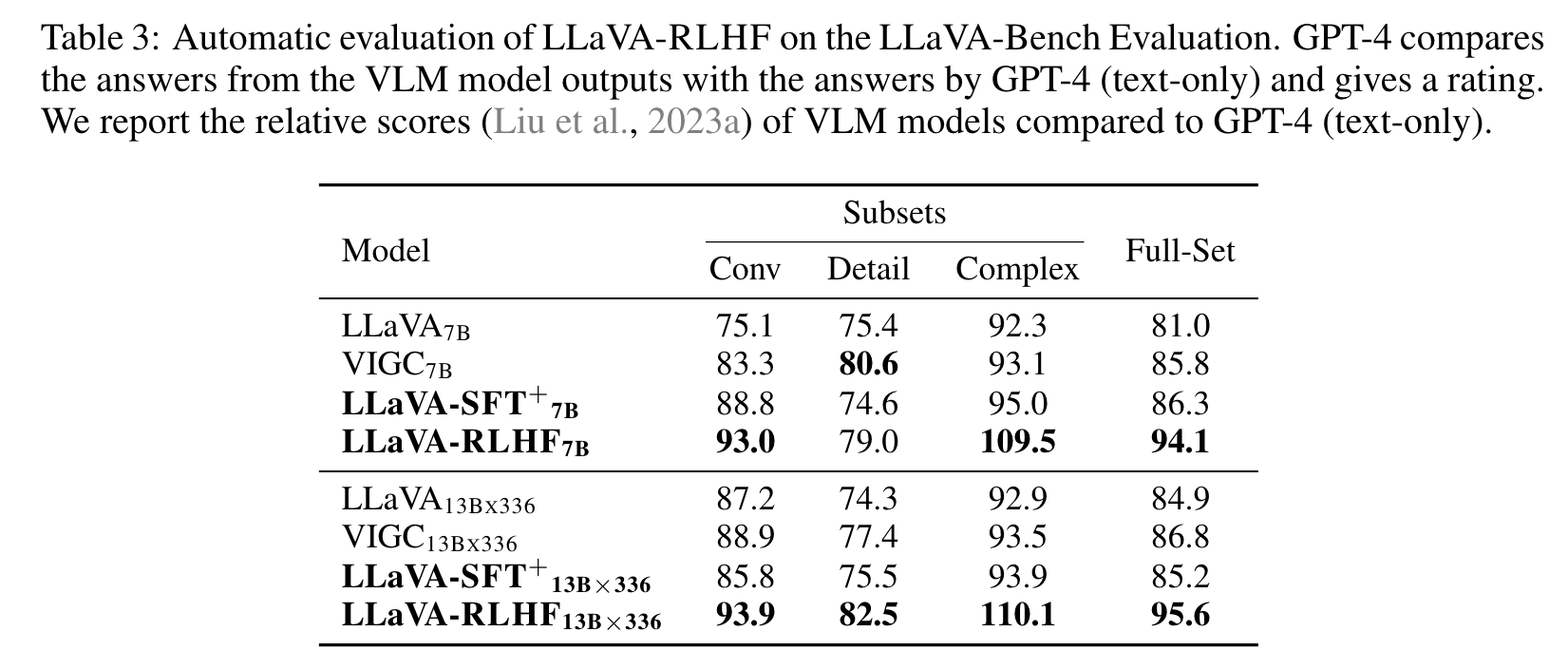

Results

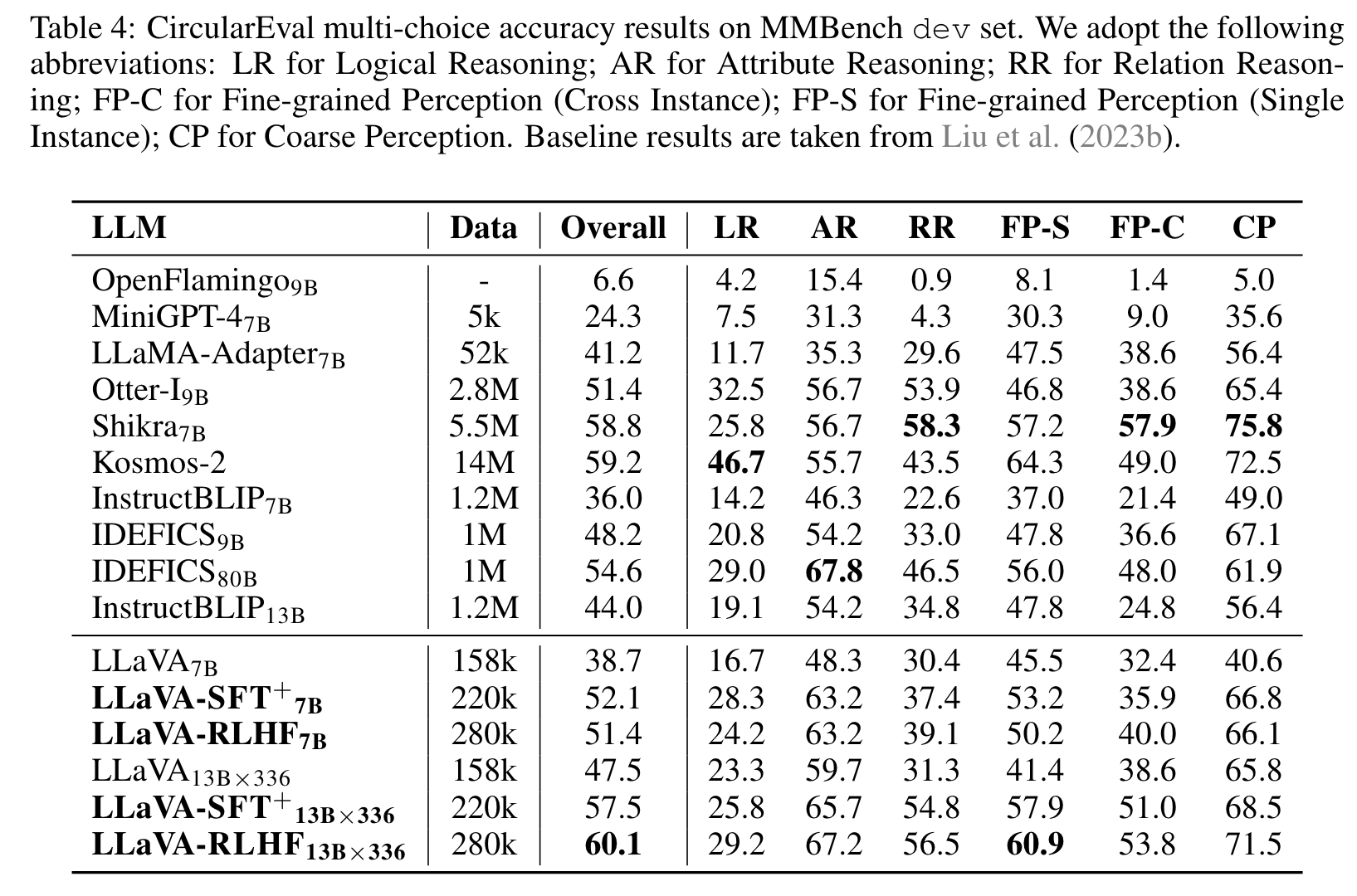

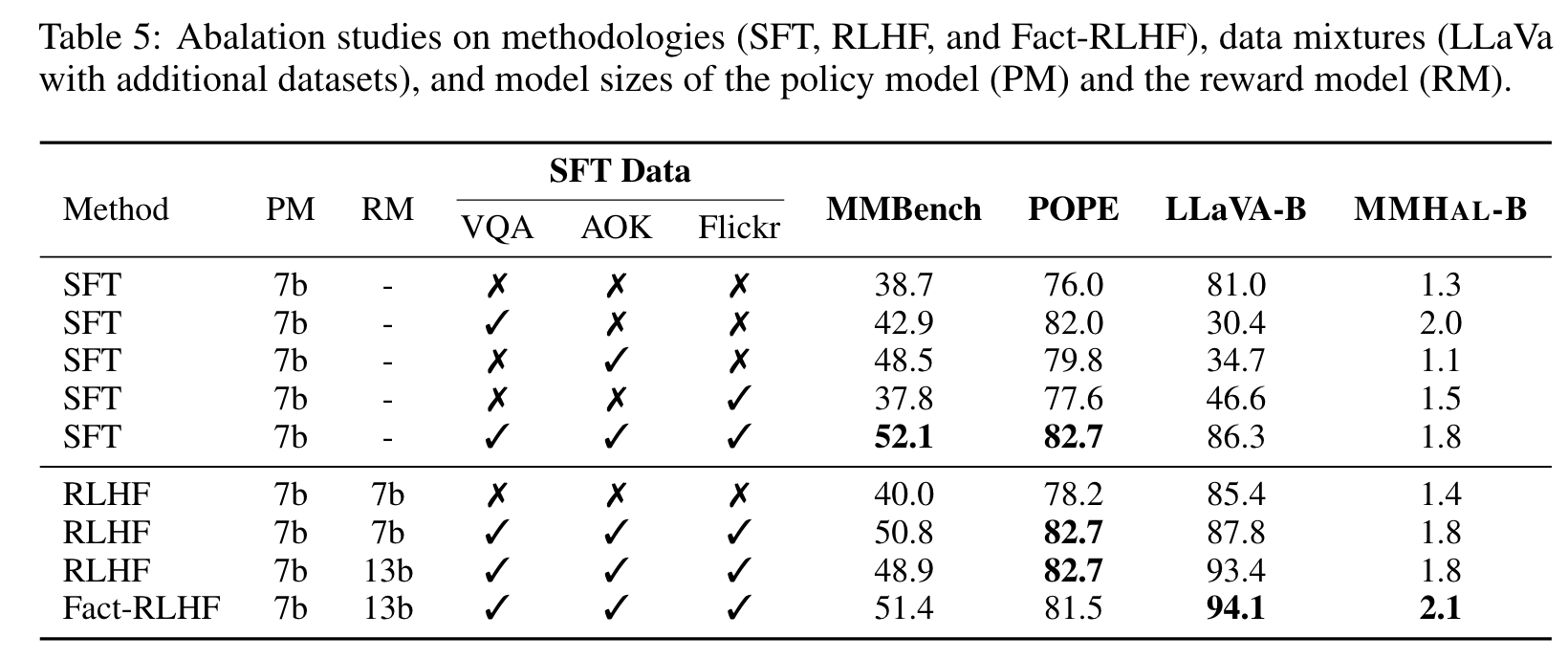

High-quality SFT data is crucial for capability benchmarks. By delving into the specific performances for the capability benchmarks (i.e., MMBench and POPE), we observe a notable improvement in capabilities brought by high-quality instruction-tuning data (LLaVA-SFT+) in Tables 4 and 7. (p. 8)

Ablation

Our findings indicate that while the conventional RLHF exhibits improvement on LLaVABench, it underperforms on MMHAL-BENCH. This can be attributed to the model’s tendency, during PPO, to manipulate the naive RLHF reward model by producing lengthier responses rather than ones that are less prone to hallucinations. On the other hand, our Fact-RLHF demonstrates enhancements on both LLaVA-Bench and MMHAL-BENCH. This suggests that Fact-RLHF not only better aligns with human preferences but also effectively minimizes hallucinated outputs. (p. 10)

Limitation

Hallucination phenomena are observed in both Large Language Models (LLMs) and Large Multimodal Models (LMMs). The potential reasons are two-fold. Firstly, a salient factor contributing to this issue is the low quality of instruction tuning data for current LMMs (p. 11)

Secondly, the adoption of behavior cloning training in instruction-tuned LMMs emerges as another fundamental cause (Schulman, 2023). Since the instruction data labelers lack insight into the LMM’s visual perception of an image, such training inadvertently conditions LMMs to speculate on uncertain content. To circumvent this pitfall, the implementation of reinforcement learning-based training provides a promising avenue, guiding the model to articulate uncertainties more effectively (Lin et al., 2022; Kadavath et al., 2022). Our work demonstrates a pioneering effort in this direction. Figure 3 illustrates the two sources of hallucination in current behavior cloning training of LLMs. (p. 11)

However, while LLaVA-RLHF enhances human alignment, reduces hallucination, and encourages truthfulness and calibration, applying RLHF can inadvertently dampen the performance of smallsized LMMs. Balancing alignment enhancements without compromising the capability of LMM and LLM is still an unresolved challenge. Furthermore, though we’ve demonstrated the effective use of linear projection in LLaVA with top-tier instruction data, determining an optimal mixture and scaling it to bigger models remains intricate. (p. 11)