BLIP-2 Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models

[multimodal blip2 diffusion query-former qformer deep-learning constrast-loss image-text-matching This is my reading note for BLIP-2: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models. The paper propose Q former to align the visual feature to text feature. Both visual feature and text feature are extracted from fixed models. Q former learned query and output the visual embeds to the text space.

Introduction

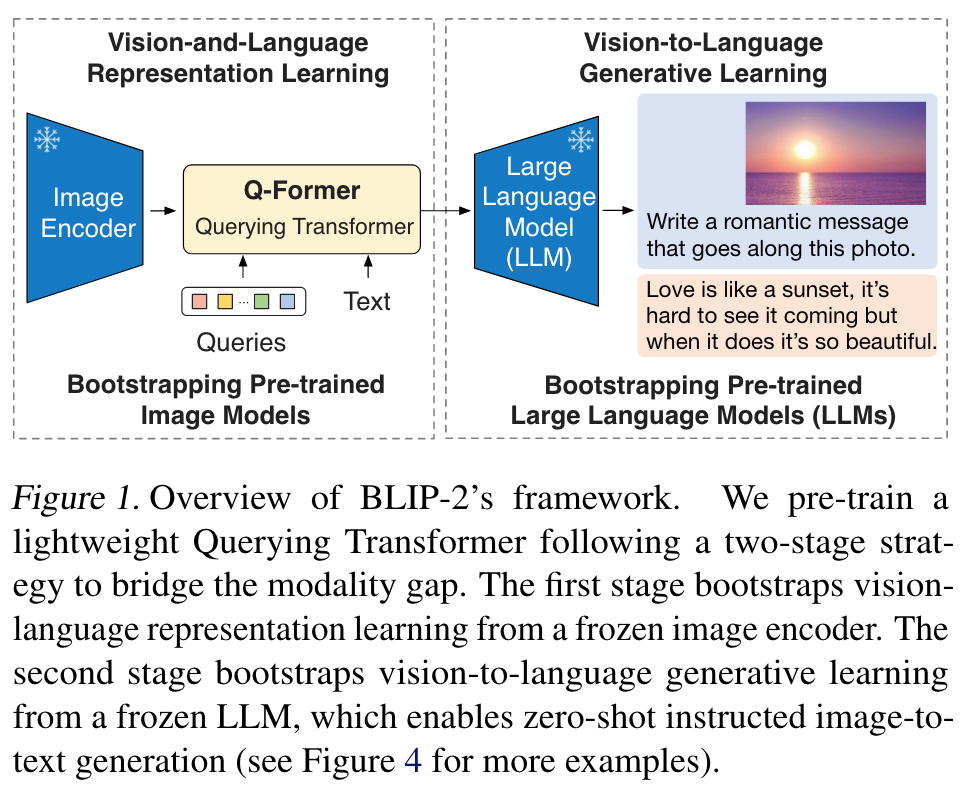

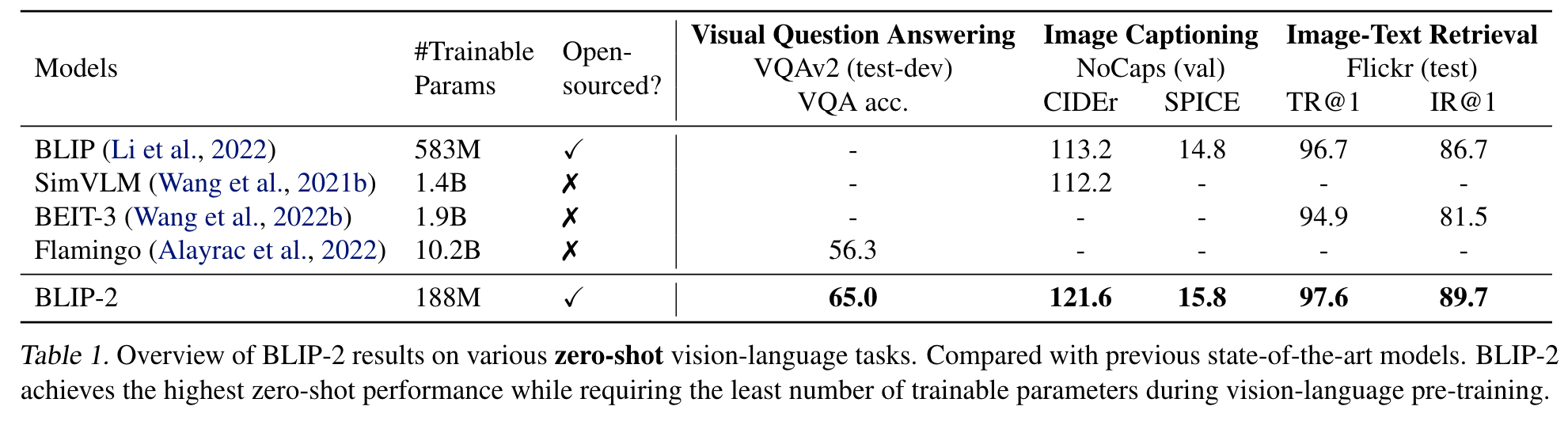

This paper proposes BLIP-2, a generic and efficient pretraining strategy that bootstraps vision-language pre-training from off-the-shelf frozen pre-trained image encoders and frozen large language models. BLIP-2 bridges the modality gap with a lightweight Querying Transformer, which is pretrained in two stages. The first stage bootstraps vision-language representation learning from a frozen image encoder. The second stage bootstraps vision-to-language generative learning from a frozen language model. (p. 1)

In order to leverage pre-trained unimodal models for VLP, it is key to facilitate cross-modal alignment. In this regard, existing methods (e.g. Frozen (Tsimpoukelli et al., 2021), Flamingo (Alayrac et al., 2022)) resort to an image-to-text generation loss, which we show is insufficient to bridge the modality gap. (p. 1)

To achieve effective vision-language alignment with frozen unimodal models, we propose a Querying Transformer (QFormer) pre-trained with a new two-stage pre-training strategy. As shown in Figure 1, Q-Former is a lightweight transformer which employs a set of learnable query vectors to extract visual features from the frozen image encoder. It acts as an information bottleneck between the frozen image encoder and the frozen LLM, where it feeds the most useful visual feature for the LLM to output the desired text. In the first pre-training stage, we perform vision-language representation learning which enforces the Q-Former to learn visual representation most relevant to the text. In the second pre-training stage, we perform vision-to-language generative learning by connecting the output of the Q-Former to a frozen LLM, and trains the Q-Former such that its output visual representation can be interpreted by the LLM. (p. 2)

Related Work

End-to-end Vision-Language Pre-training

Depending on the downstream task, different model architectures have been proposed, including the dual-encoder architecture (Radford et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2021), the fusion-encoder architecture (Tan & Bansal, 2019; Li et al., 2021), the encoder-decoder architecture (Cho et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021b; Chen et al., 2022b), and more recently, the unified transformer architecture (Li et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022b). Various pre-training objectives have also been proposed over the years, and have progressively converged to a few time-tested ones: image-text contrastive learning (Radford et al., 2021; Yao et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021; 2022), image-text matching (Li et al., 2021; 2022; Wang et al., 2021a), and (masked) language modeling (Li et al., 2021; 2022; Yu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022b). (p. 2)

Most VLP methods perform end-to-end pre-training using large-scale image-text pair datasets. As the model size keeps increasing, the pre-training can incur an extremely high computation cost. Moreover, it is inflexible for end-to-end pre-trained models to leverage readily-available unimodal pre-trained models, such as LLMs (p. 2)

Modular Vision-Language Pre-training

More similar to us are methods that leverage off-the-shelf pre-trained models and keep them frozen during VLP. The key challenge in using a frozen LLM is to align visual features to the text space. To achieve this, Frozen (Tsimpoukelli et al., 2021) finetunes an image encoder whose outputs are directly used as soft prompts for the LLM. Flamingo (Alayrac et al., 2022) inserts new cross-attention layers into the LLM to inject visual features, and pre-trains the new layers on billions of image-text pairs. Both methods adopt the language modeling loss, where the language model generates texts conditioned on the image. (p. 2)

Method

Model Architecture

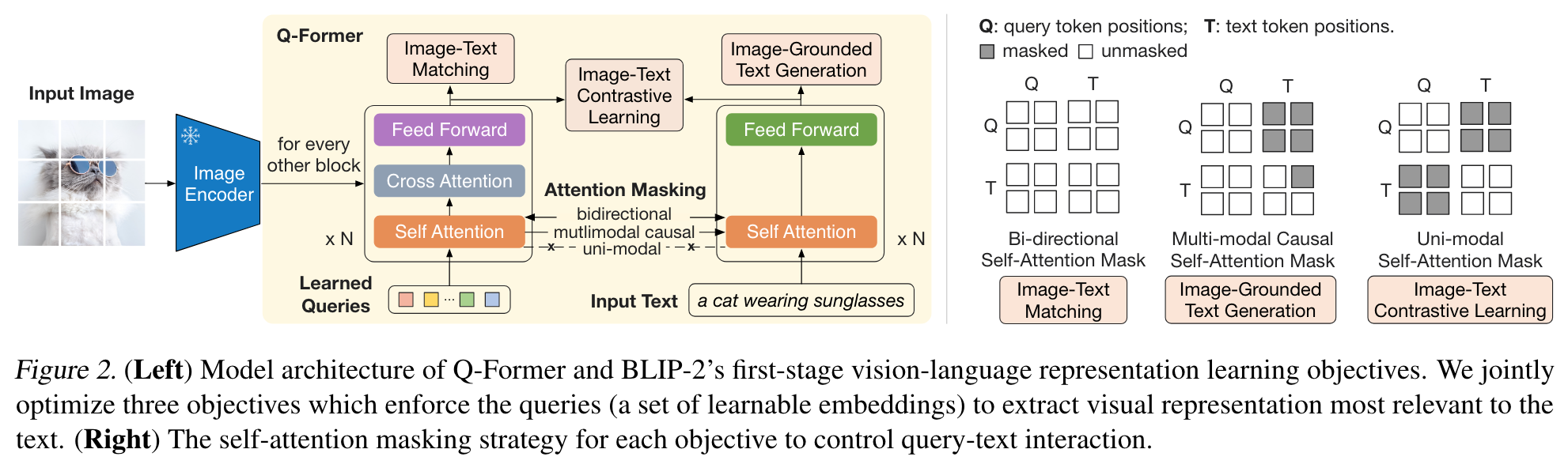

It extracts a fixed number of output features from the image encoder, independent of input image resolution. As shown in Figure 2, Q-Former consists of two transformer submodules that share the same self-attention layers:

- an image transformer that interacts with the frozen image encoder for visual feature extraction,

- a text transformer that can function as both a text encoder and a text decoder. We create a set number of learnable query embeddings as input to the image transformer. The queries interact with each other through self-attention layers, and interact with frozen image features through cross-attention layers (inserted every other transformer block). The queries can additionally interact with the text through the same self-attention layers. Depending on the pre-training task, we apply different self-attention masks to control query-text interaction. We initialize QFormer with the pre-trained weights of BERTbase (Devlin et al., 2019), whereas the cross-attention layers are randomly initialized. In total, Q-Former contains 188M parameters. Note that the queries are considered as model parameters. (p. 3)

In our experiments, we use 32 queries where each query has a dimension of 768 (same as the hidden dimension of the Q-Former). (p. 3)

Bootstrap Vision-Language Representation Learning from a Frozen Image Encoder

In the representation learning stage, we connect Q-Former to a frozen image encoder and perform pre-training using image-text pairs. We aim to train the Q-Former such that the queries can learn to extract visual representation that is most informative of the text. Inspired by BLIP (Li et al., 2022), we jointly optimize three pre-training objectives that share the same input format and model parameters. Each objective employs a different attention masking strategy between queries and text to control their interaction (see Figure 2). (p. 3)

Image-Text Contrastive Learning

Since Z contains multiple output embeddings (one from each query), we first compute the pairwise similarity between each query output and t, and then select the highest one as the image-text similarity. To avoid information leak, we employ a unimodal self-attention mask, where the queries and text are not allowed to see each other (p. 3)

Image-Text Matching

It is a binary classification task where the model is asked to predict whether an image-text pair is positive (matched) or negative (unmatched). We use a bi-directional self-attention mask where all queries and texts can attend to each other. (p. 3)

Bootstrap Vision-to-Language Generative Learning from a Frozen LLM

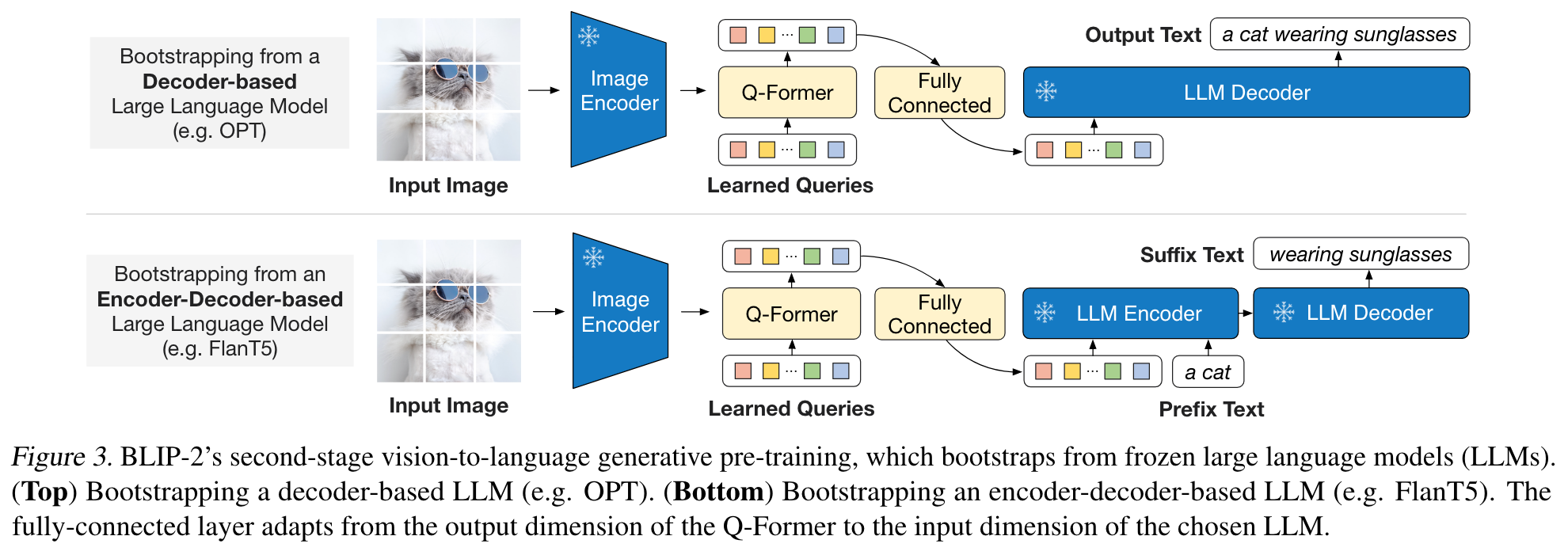

In the generative pre-training stage, we connect QFormer (with the frozen image encoder attached) to a frozen LLM to harvest the LLM’s generative language capability. The projected query embeddings are then prepended to the input text embeddings. They function as soft visual prompts that condition the LLM on visual representation extracted by the Q-Former. Since the Q-Former has been pre-trained to extract language-informative visual representation, it effectively functions as an information bottleneck that feeds the most useful information to the LLM while removing irrelevant visual information. This reduces the burden of the LLM to learn vision-language alignment, thus mitigating the catastrophic forgetting problem. (p. 4)

We experiment with two types of LLMs: decoder-based LLMs and encoder-decoder-based LLMs. For decoder based LLMs, we pre-train with the language modeling loss, where the frozen LLM is tasked to generate the text conditioned on the visual representation from Q-Former. For encoder-decoder-based LLMs, we pre-train with the prefix language modeling loss, where we split a text into two parts. The prefix text is concatenated with the visual representation as input to the LLM’s encoder. The suffix text is used as the generation target for the LLM’s decoder. (p. 4)

Experiment

Limitation

However, our experiments with BLIP-2 do not observe an improved VQA performance when providing the LLM with in-context VQA examples. We attribute the lack of in-context learning capability to our pretraining dataset, which only contains a single image-text pair per sample. The LLMs cannot learn from it the correlation among multiple image-text pairs in a single sequence. The same observation is also reported in the Flamingo paper, which uses a close-sourced interleaved image and text dataset (M3W) with multiple image-text pairs per sequence. We aim to create a similar dataset in future work.

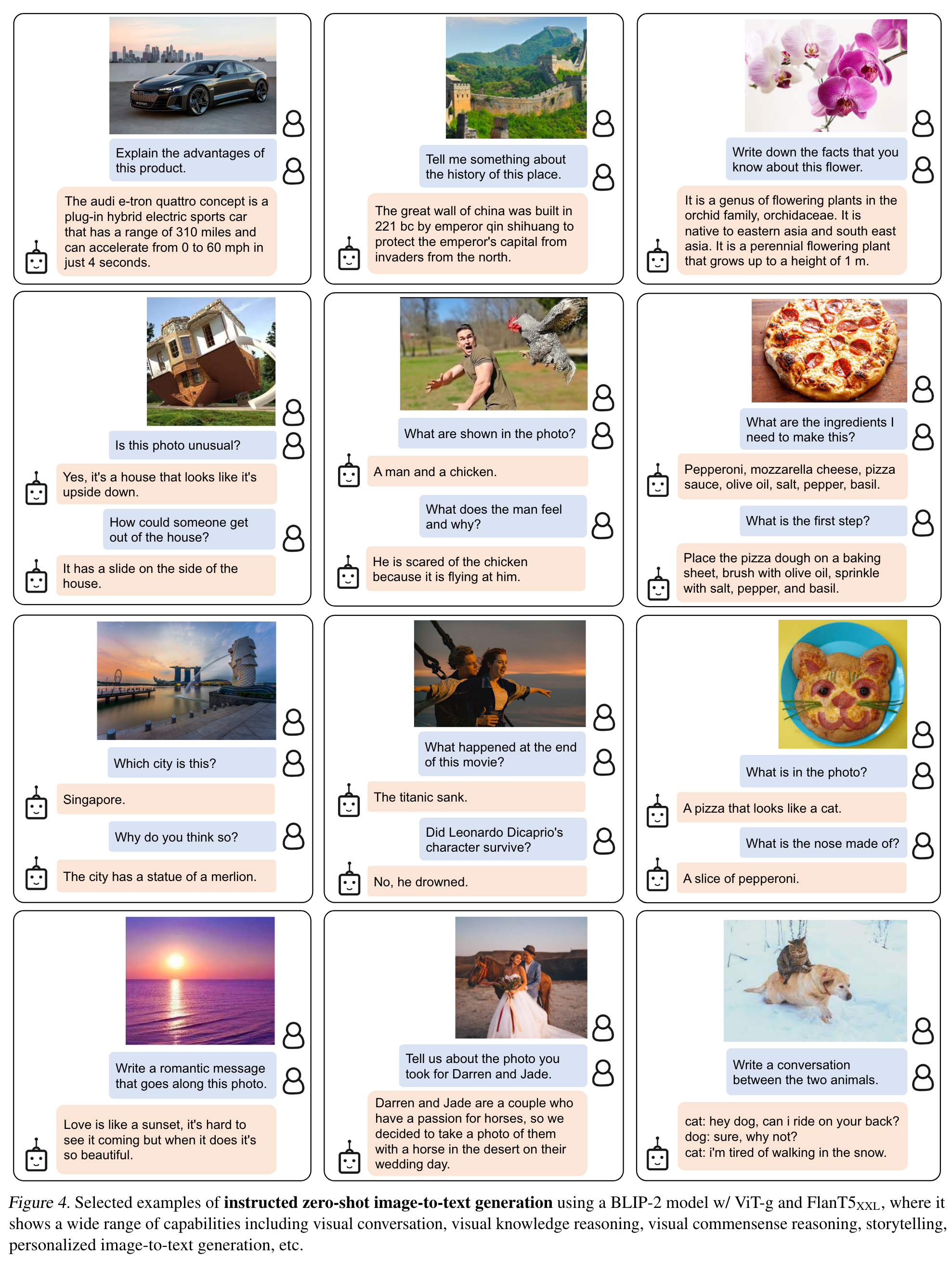

BLIP-2’s image-to-text generation could have unsatisfactory results due to various reasons including inaccurate knowledge from the LLM, activating the incorrect reasoning path, or not having up-to-date information about new image content (see Figure 7). Furthermore, due to the use of frozen models, BLIP-2 inherits the risks of LLMs, such as outputting offensive language, propagating social bias, or leaking private information. Remediation approaches include using instructions to guide model’s generation or training on a filtered dataset with harmful content removed. (p. 8)