Rerender A Video Zero-Shot Text-Guided Video-to-Video Translation

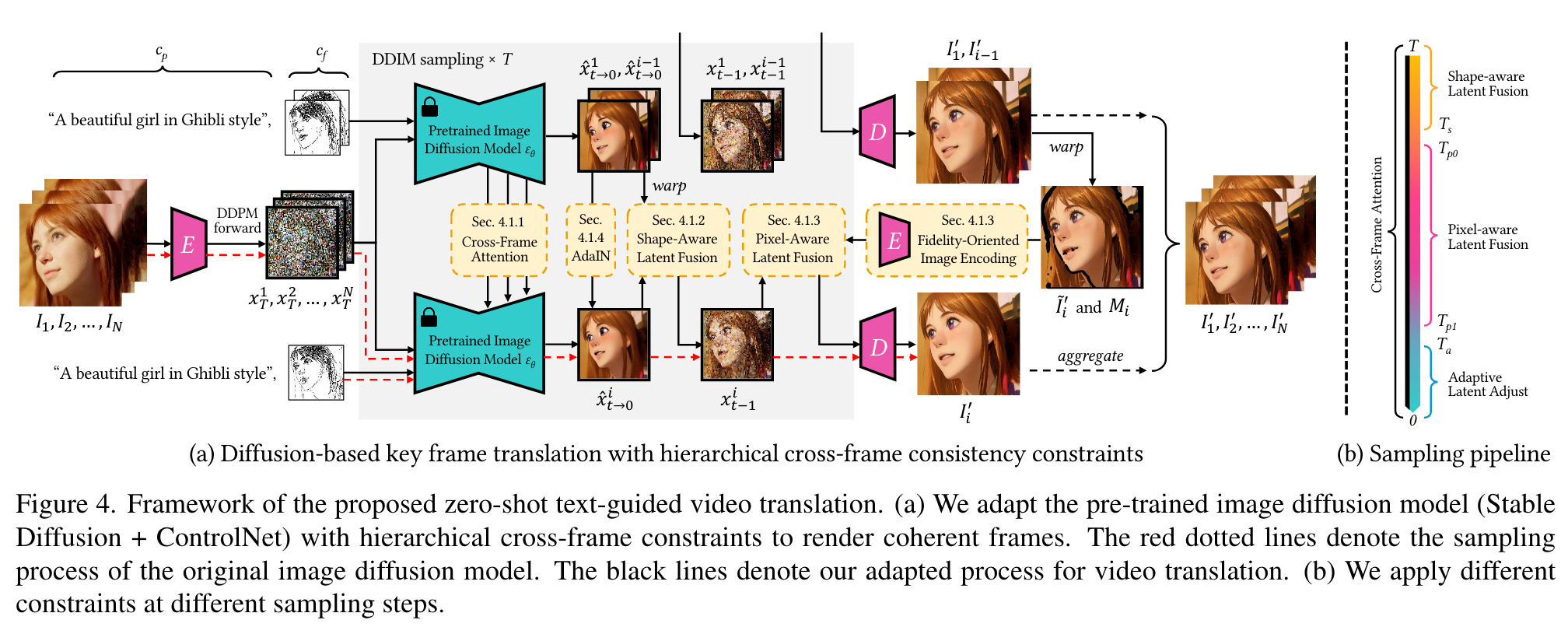

[null-text-inversion video key-frame dreamix diffusion pix2video deep-learning edit-a-video text2video prompt2prompt ebsynth fatezero video-p2p make-a-video video-diffusion tune-a-video text2video-zero optical-flow imagen-video vid2vid-zero This is my reading note on Rerender A Video: Zero-Shot Text-Guided Video-to-Video Translation. The paper proposes a method to edit a video given style mentioned in prompt. The method performed diffusion to edit key frames and then propagate the edited key frames to other frames using optical flow. For key frame editing, several attention based constraint is applied to reserve details and consistency, including shape aware, style aware, pixel aware and fidelity aware.

Introduction

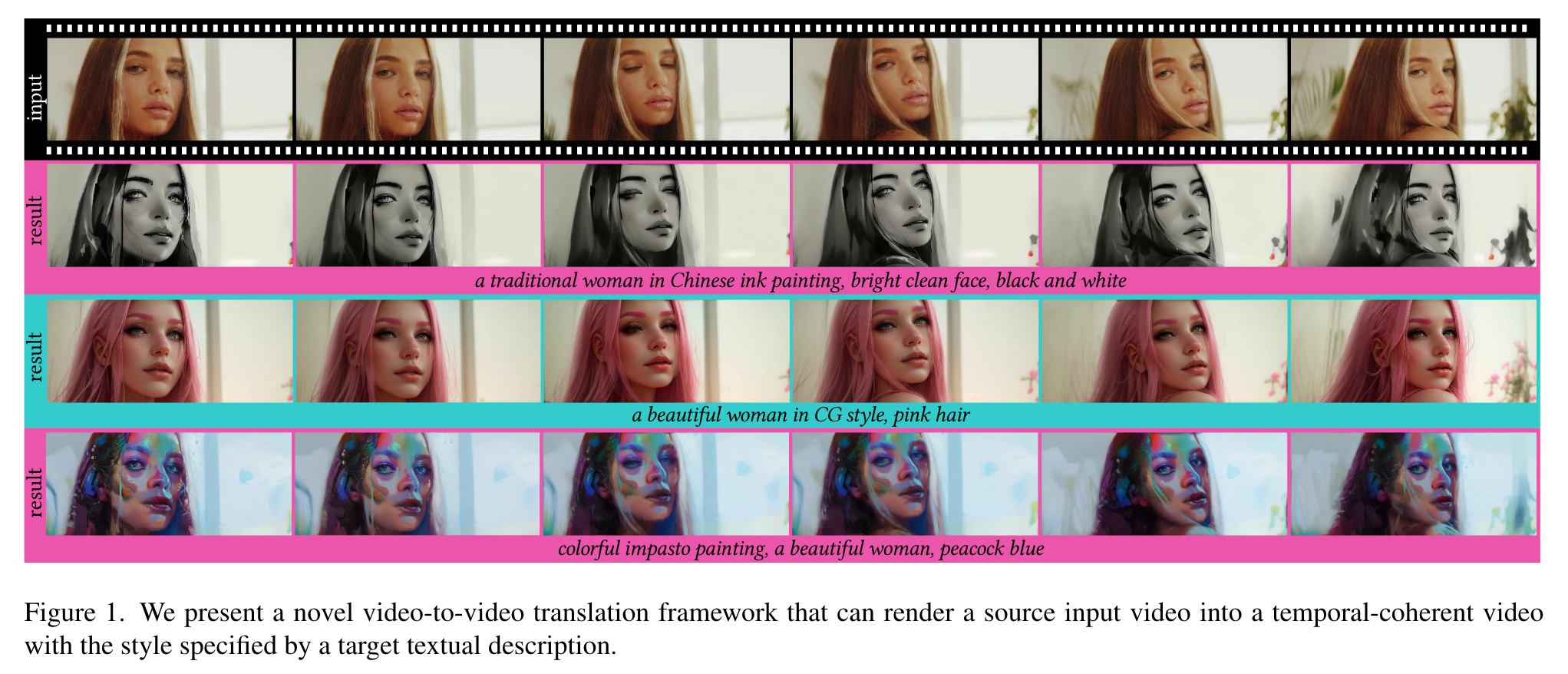

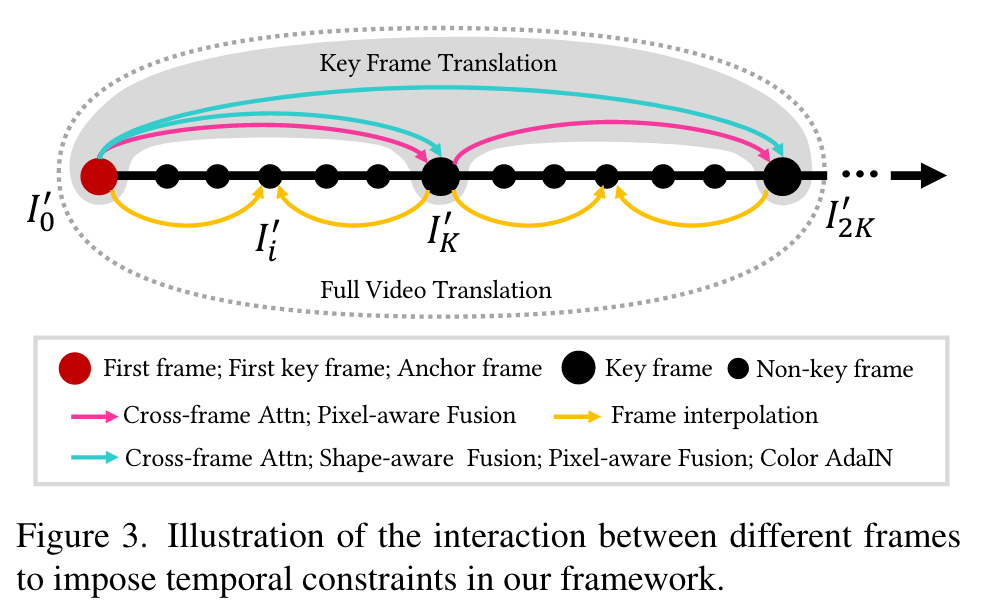

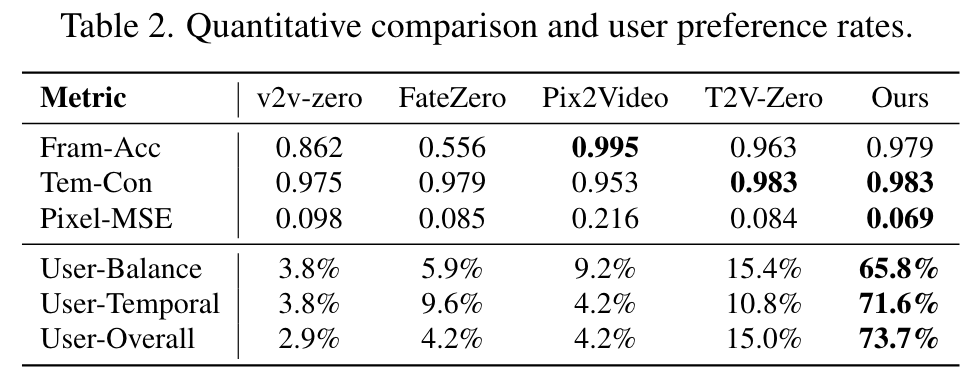

This paper proposes a novel zeroshot text-guided video-to-video translation framework to adapt image models to videos. The framework includes two parts: key frame translation and full video translation. The first part uses an adapted diffusion model to generate key frames, with hierarchical cross-frame constraints applied to enforce coherence in shapes, textures and colors. The second part propagates the key frames to other frames with temporal-aware patch matching and frame blending. Our framework achieves global style and local texture temporal consistency at a low cost (without re-training or optimization). The adaptation is compatible with existing image diffusion techniques, allowing our framework to take advantage of them (p. 1)

Yet, a critical challenge remains: the direct application of existing image diffusion models to videos leads to severe flickering issues. (p. 1)

- The first solution involves training a video model on large-scale video data [14], which requires significant computing resources. Additionally, the re-designed video model is incompatible with existing off-the-shelf image models.

- The second solution is to fine-tune image models on a single video [40], which is less efficient for long videos. Overfitting to a single video may also degrade the performance of the original models.

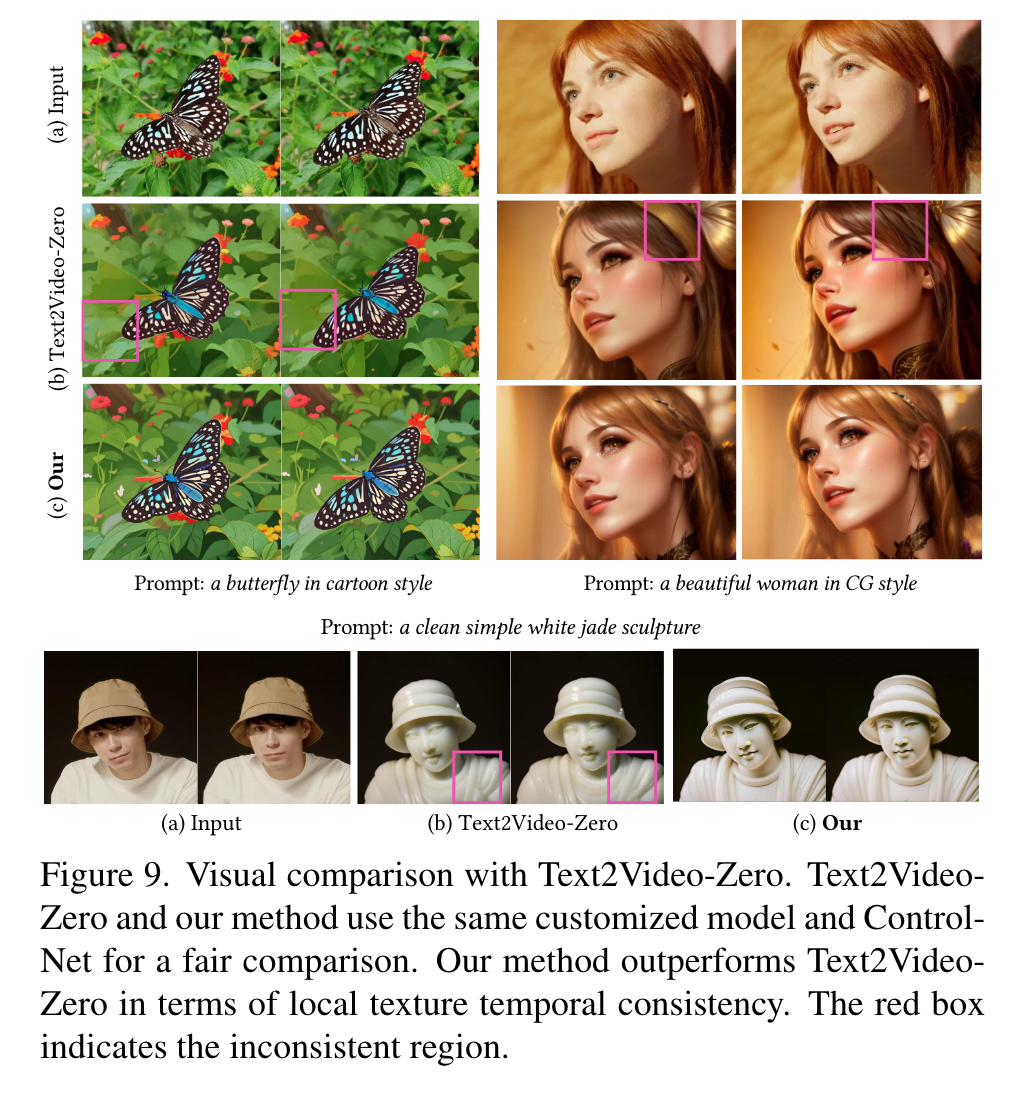

- The third solution involves zero-shot methods [20] that require no training. During the diffusion sampling process, cross-frame constraints are imposed on the latent features for temporal consistency. The zero-shot strategy requires fewer computing resources and is mostly compatible with existing image models, showing promising potential. However, current cross-frame constraints are limited to global styles and are unable to preserve low-level consistency, e.g., the overall style may be consistent, but the local structures and textures may still flicker. (p. 2)

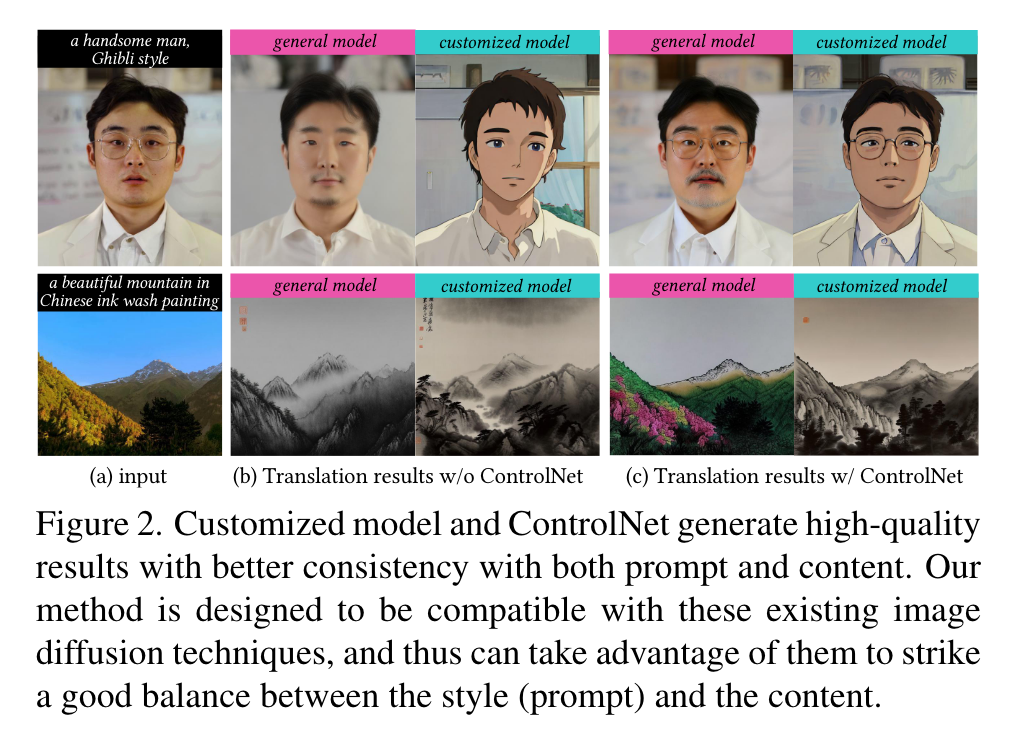

Achieving successful application of image diffusion models to the video domain is a challenging task. It requires

- Temporal consistency: cross-frame constraints for low-level consistency;

- Zero-shot: no training or finetuning required;

- Flexibility: compatible with off-theshelf image models for customized generation. As mentioned above, image models can be customized by finetuning on specific objects to capture the target style more precisely than general models. Figure 2 shows two examples. To take advantage of it, in this paper, we employ zero-shot strategy for model compatibility and aim to further solve the key issue of this strategy in maintaining lowlevel temporal consistency. (p. 2)

To achieve this goal, we propose novel hierarchical cross-frame constraints for pre-trained image models to produce coherent video frames. Our key idea is to use optical flow to apply dense cross-frame constraints, with the previous rendered frame serving as a low-level reference for the current frame and the first rendered frame acting as an anchor to regulate the rendering process to prevent deviations from the initial appearance. Hierarchical crossframe constraints are realized at different stages of diffusion sampling. In addition to global style consistency, our method enforces consistency in shapes, textures and colors at early, middle and late stages, respectively. This innovative and lightweight modification achieves both global and local temporal consistency (p. 2)

Related Work

For text-to-video generation, Video Diffusion Model [16] proposes to extend the 2D U-Net in image model to a factorized space-time UNet. Imagen Video [14] scales up the Video Diffusion Model with a cascade of spatial and temporal video super-resolution models, which is further extended to video editing by Dreamix [25]. Make-A-Video [36] leverages video data in an unsupervised manner to learn the movement to drive the image model. Although promising, the above methods need large-scale video data for training. Tune-A-Video [40] instead inflates an image diffusion model into a video model with cross-frame attention, and fine-tunes it on a single video to generate videos with related motion. Based on it, Edit-A-Video [35], VideoP2P [22] and vid2vid-zero [39] utilize Null-Text Inversion [24] for precise inversion to preserve the unedited region. However, these models need fine-tuning of the pretrained model or optimization over the input video, which is less efficient. (p. 3)

Based on the editing masks detected by Prompt2Prompt [12] to indicate the channel and spatial region to preserve, FateZero [27] blends the attention features before and after editing. Text2Video-Zero [20] translates the latent to directly simulate motions and Pix2Video [3] matches the latent of the current frame to that of the previous frame. All the above methods largely rely on crossframe attention and early-step latent fusion to improve temporal consistency. However, as we will show later, these strategies predominantly cater to high-level styles and shapes, and being less effective in maintaining crossframe consistency at the level of texture and detail. (p. 3)

Another zero-shot solution is to apply frame interpolation to infer the videos based on one or more diffusionedited frames. The seminal work of image analogy [13] migrates the style effect from an exemplar pair to other images with patch matching. Fiser ˇ et al. [8] extend image analogy to facial video translation with the guidance of facial features. Later, Jamrivska ˇ et al. [19] propose an improved EbSynth for general video translation based on multiple exemplar frames with a novel temporal blending approach. Although these patch-based methods can preserve fine details, their temporal consistency largely relies on the coherence across the exemplar frames. (p. 3)

Proposed Method

Key Frame Translation

Specifically, cross-frame attention [40] is applied to all sampling steps for global style consistency (Sec. 4.1.1). In addition, in early steps, we fuse the latent feature with the aligned latent feature of previous frame to achieve rough shape alignments (Sec. 4.1.2). Then in mid steps, we use the latent feature with the encoded warped anchor and previous outputs to realize fine texture alignments (Sec. 4.1.3). Finally, in late steps, we adjust the latent feature distribution for color consistency (Sec. 4.1.4). For simplicity, we will use {Ii}N i=0 to refer to the key frames in this section. We summarize important notations in Table 1. (p. 4)

Style-aware cross-frame attention

Similar to other zero-shot video editing methods [3, 20], we replace self-attention layers in the U-Net with crossframe attention layers to regularize the global style of I′ i to match that of I′1 and I′ i−1. (p. 5)

Cross-frame attention, by comparison, uses the key K′ and value V ′ from other frames (we use the first and previous frames), i.e., CrossFrame Attn(Q, K′, V ′) = Softmax( QK′T √d ) · V ′ with (p. 5)

Shape-aware cross-frame latent fusion

Let wi j and Mi j denote the optical flow and occlusion mask from Ij to Ii, respectively. Let xi t be the latent feature for I′ i at time step t. We update the predicted xˆt→0 in Eq. (3) by (p. 5)

For the reference frame Ij , we experimentally find that the anchor frame (j = 0) provides better guidance than the previous frame (j = i − 1). We observe that interpolating elements in the latent space can lead to blurring and shape distortion in the late steps. Therefore, we limit the fusion to only early steps for rough shape guidance. (p. 5)

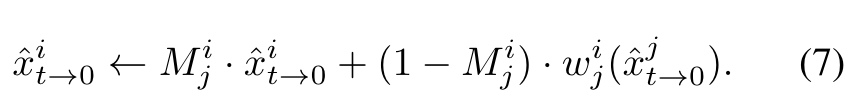

Pixel-aware cross-frame latent fusion

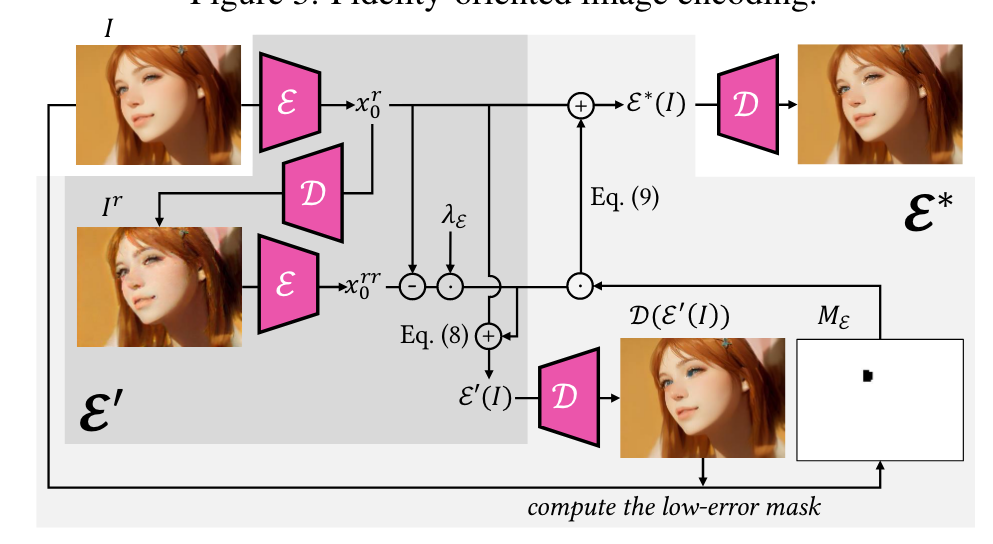

To constrain the low-level texture features in mid steps, instead warping the latent feature, we can alternatively warp previous frames and encode them back to the latent space for fusion in an inpainting manner. However, the lossy autoencoder introduces distortions and color bias that easily accumulate along the frame sequence. To efficiently solve this problem, we propose a novel fidelity-oriented zero-shot image encoding method. (p. 5)

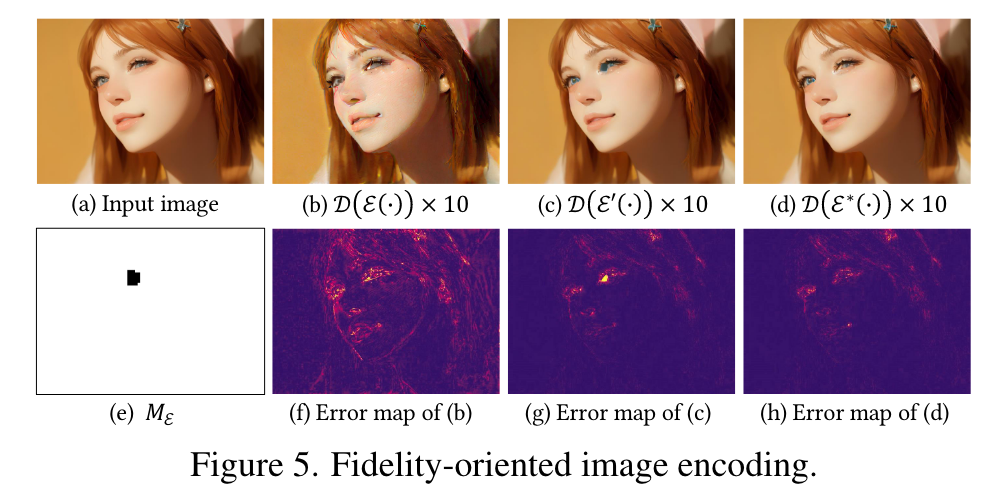

Fidelity-oriented image encoding

Our key insight is the observation that the amount of information lost each time in the iterative auto-encoding process is consistent. Therefore, we can predict the information loss for compensation. (p. 5)

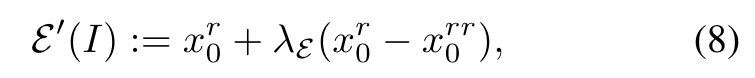

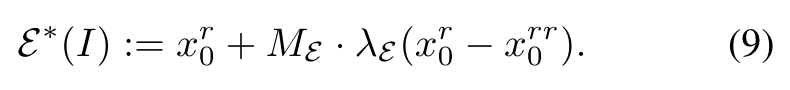

We further add a mask ME to prevent the possible artifacts introduced by compensation (e.g., blue artifact near the eyes in Fig. 5(c)). ME indicates where the error between I and D(E′(I)) is under a pre-defined threshold. Then, our novel fidelity-oriented image encoding E∗ takes the form of (p. 5)

Structure-guided inpainting

for pixel-level coherence, we warp the anchor frame I′0 and the previous frame I′ i−1 to the i-th frame and overlay them on a rough rendered frame ¯I′ i obtained without the pixel-aware cross-frame latent fusion as (p. 6)

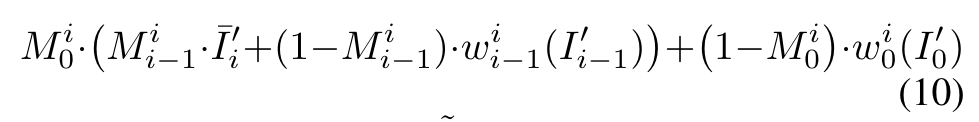

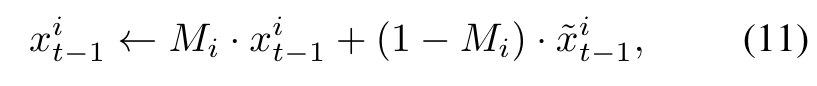

The resulting fused frame ˜I′ i provides pixel reference for the sampling of I′ i , i.e., we would like I′ i to match ˜I′ i outside the mask area Mi = Mi 0 ∩ Mi i−1 and to match the structure guidance from ControlNet inside Mi. We formulate it as a structure-guided inpainting task and follow [1] to update xi t−1 in Eq. (3) as (p. 6)

Color-aware adaptive latent adjustment

Finally, we apply AdaIN [18] to xˆi t→0 to match its channelwise mean and variance to xˆ1t→0 in the late steps. It can further keep the color style coherent throughout the whole key frames (p. 6)

Full Video Translation

For frames with similar content, existing frame interpolation methods like Ebsynth [19] can generate plausible results by propagating the rendered frames to their neighbors efficiently. However, compared to diffusion models, frame interpolation cannot create new content. To balance between quality and efficiency, we propose a hybrid framework to render key frames and other frames with the adapted diffusion model and Ebsynth, respectively. (p. 6)

Specifically, we sample the key frames uniformly for every K frame, i.e., I0, IK, I2K, … and render them to I′0, I′K, I′2K, … by our adapted diffusion model. We then render the remaining non-key frames. Taking Ii (0 < i < K) for example, we adopt Ebsynth to interpolate I′ i with its neighboring stylized key frames I′0 and I′K. (p. 6)

Single key frame propagation

Frame propagation aims to warp the stylized key frame to its neighboring non-key frames based on their dense correspondences. We directly follow Ebsynth to adopt a guided path-matching algorithm with color, positional, edge, and temporal guidance for dense correspondence prediction and frame warping. Our framework propagates each key frame to its preceding K − 1 and succeeding K − 1 frames (p. 6)

Temporal-aware blending

Frame blending aims to blend I′^0_i and I′^K_i to a final result I′_i . Ebsynth proposes a three-step blending scheme: 1

- Combining colors and gradients of I′^0_i and I′^K_i by selecting the ones with lower errors during patch matching (Sec. 4.2.1) for each location;

- Using the combined color image as a histogram reference for contrast-preserving blending [11] over I′^0_i and I′^K_i to generate an initial blended image;

- Employing the combined gradient as a gradient reference for screened Poisson blending [5] over the initial blended image to obtain the final result. Differently, our framework only adopts the first two blending steps and uses the initial blended image as I′_i . We do not apply Poisson blending, which we find sometimes causes artifacts in non-flat regions and is relatively time-consuming. (p. 6)

Experiment

Ablation Studies

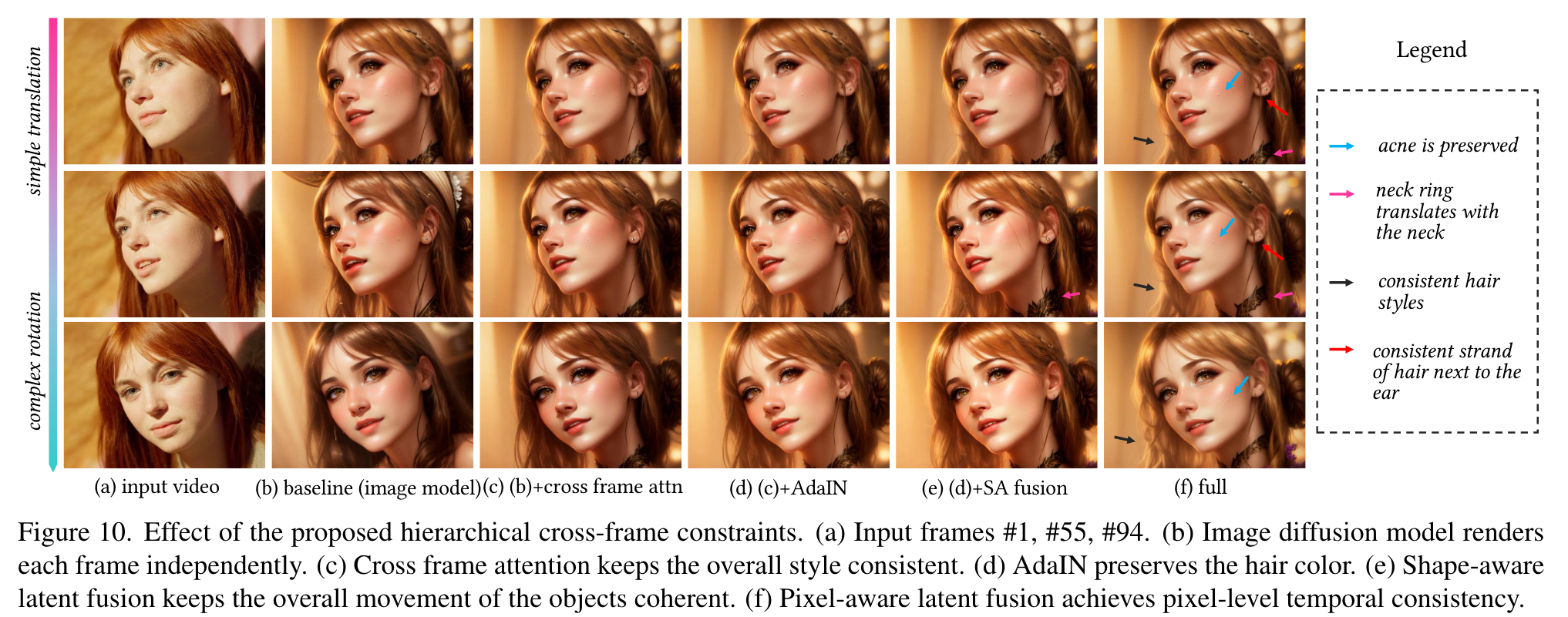

Hierarchical cross-frame consistency constraints

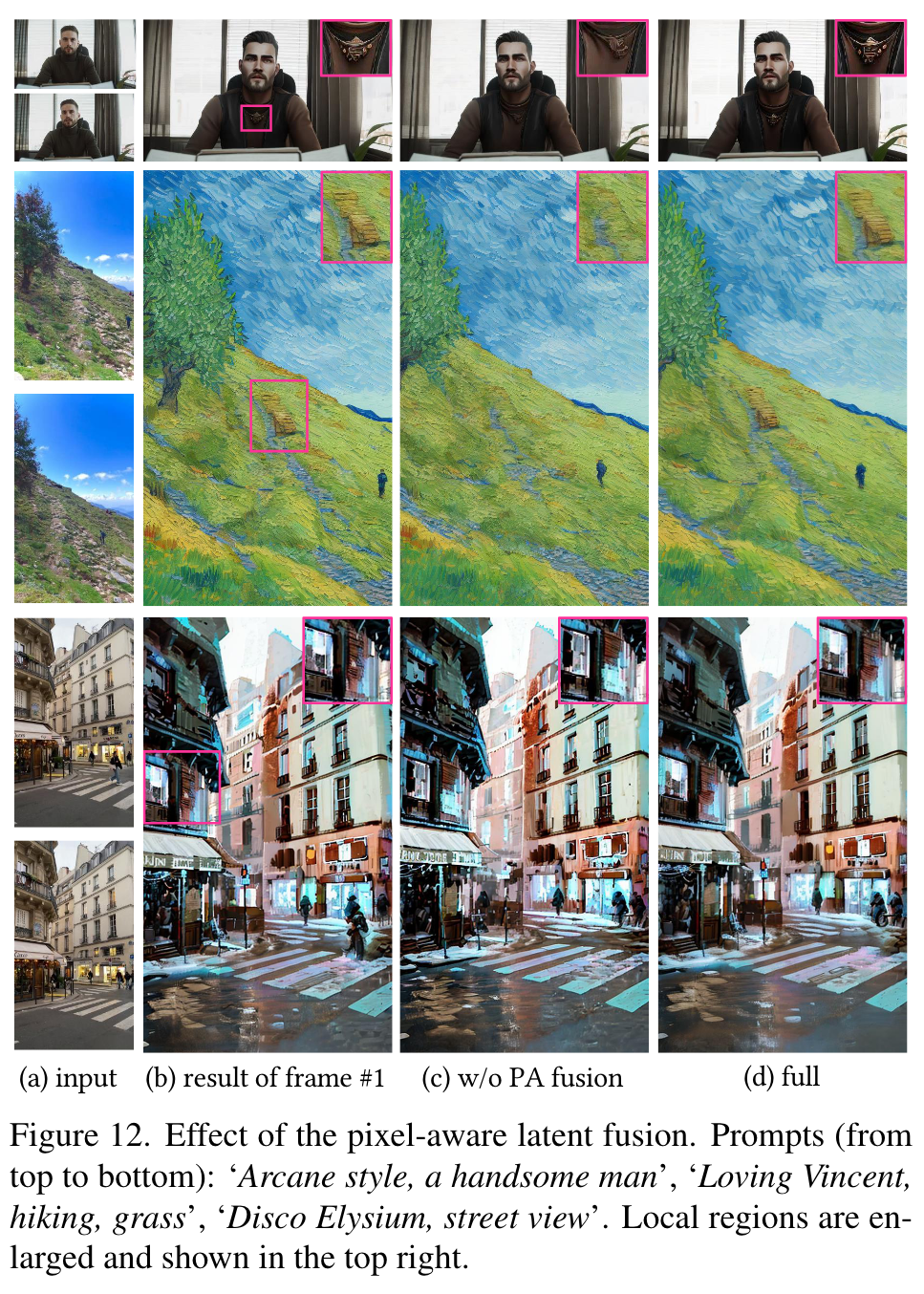

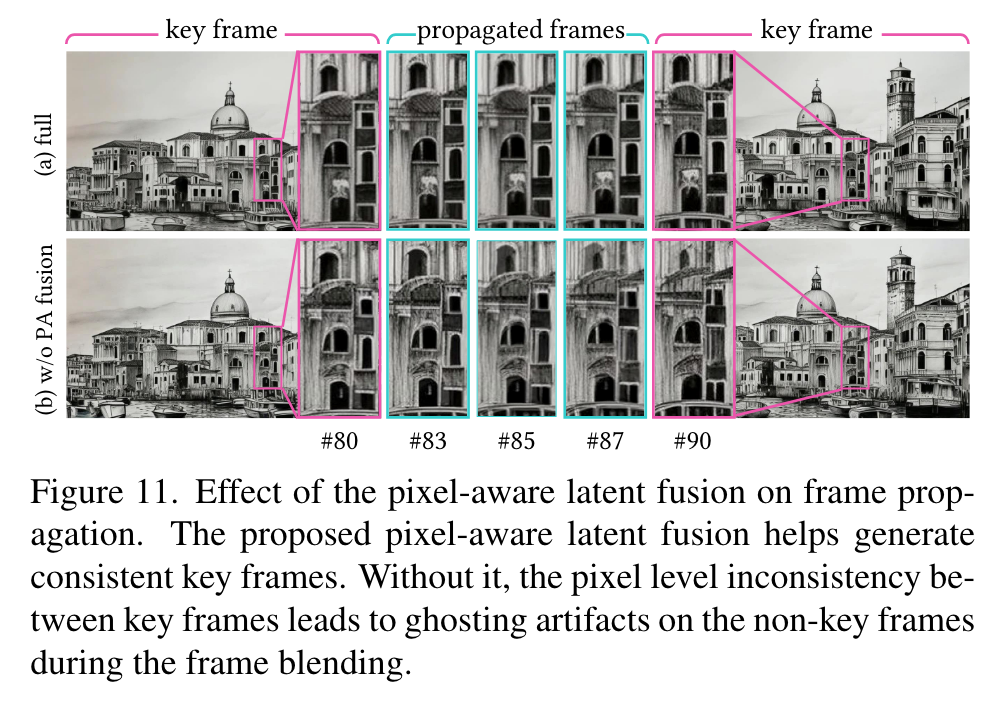

The cross-frame attention ensures consistency in global style, while the adaptive latent adjustment in Sec. 4.1.4 maintains the same hair color as the first frame, or the hair color will follow the input frame to turn dark. The above two global constraints cannot capture local movement. The shape-aware latent fusion (SA fusion) in Sec. 4.1.2 addresses this by translating the latent features to translate the neck ring, but cannot maintain pixel-level consistency for complex motion. Only the proposed pixelaware latent fusion (PA fusion) can coherently render local details such as hair styles and acne. (p. 8)

While ControlNet can guide the structure well, the inherent randomness introduced by noise addition and denoising makes it difficult to maintain coherence in local textures, resulting in missing elements and altered details. The proposed PA fusion restores these details by utilizing the corresponding pixel information from previous frames. Moreover, such consistency between key frames can effectively reduce the ghosting artifacts in interpolated non key frames. (p. 8)

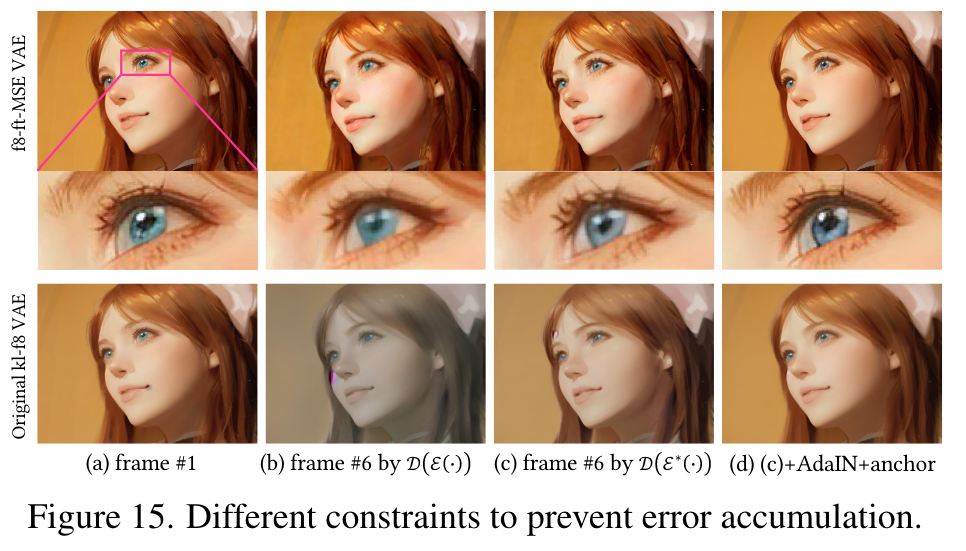

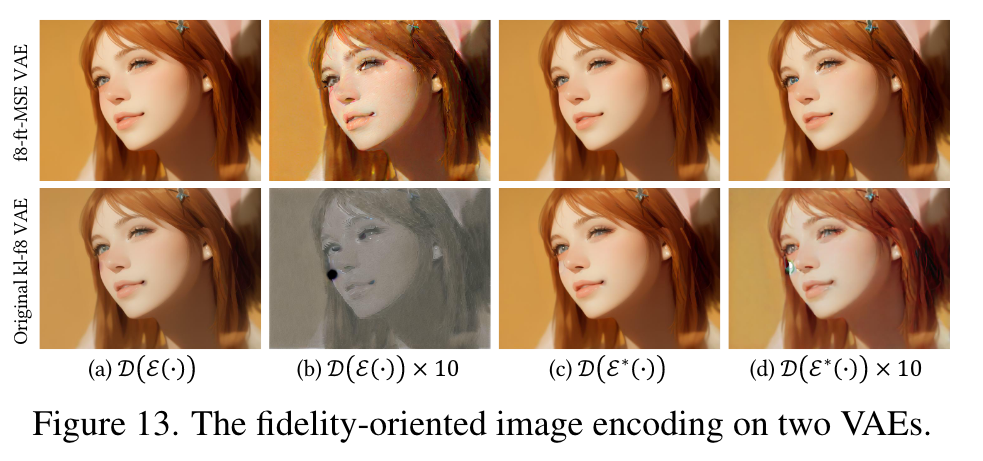

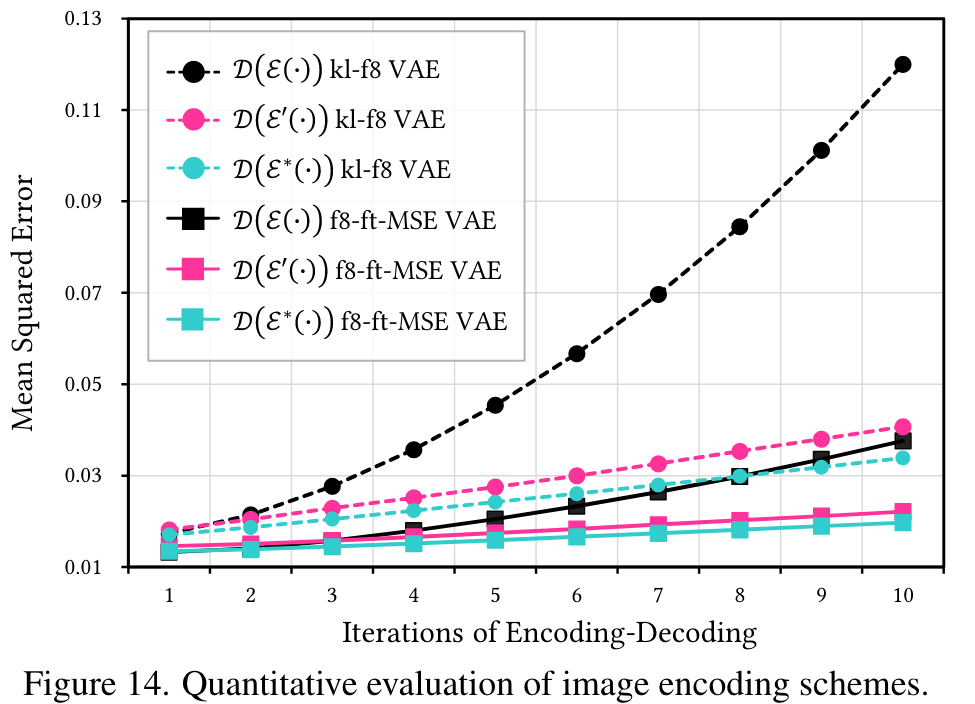

Fidelity-oriented image encoding

The fine-tuned VAE introduces artifacts and the original VAE results in great color bias as in Fig. 13(b). Our proposed fidelity-oriented image encoding effectively alleviates these issues. (p. 8)

The results are consistent with the visual observations: our proposed method significantly reduces error accumulation compared to raw encoding methods. Finally, we validate our encoding method in the video translation process in Fig. 15(b)(c), where we use only the previous frame without the anchor frame in Eq. (10) to better visualize error accumulation. Our method mostly reduces the loss of details and color bias caused by lossy encoding. Besides, our pipeline includes an anchor frame and adaptive latent adjustment to further regulate the translation, as shown in Fig. 15(d), where no obvious errors are observed. (p. 8)

Frequency of key frames

With large K, more frame interpolation improves pixel-level temporal consistency, which however harms the quality, leading to low Fram-Acc. A broad range of K ∈ [5, 20] is recommended for balance. (p. 8)

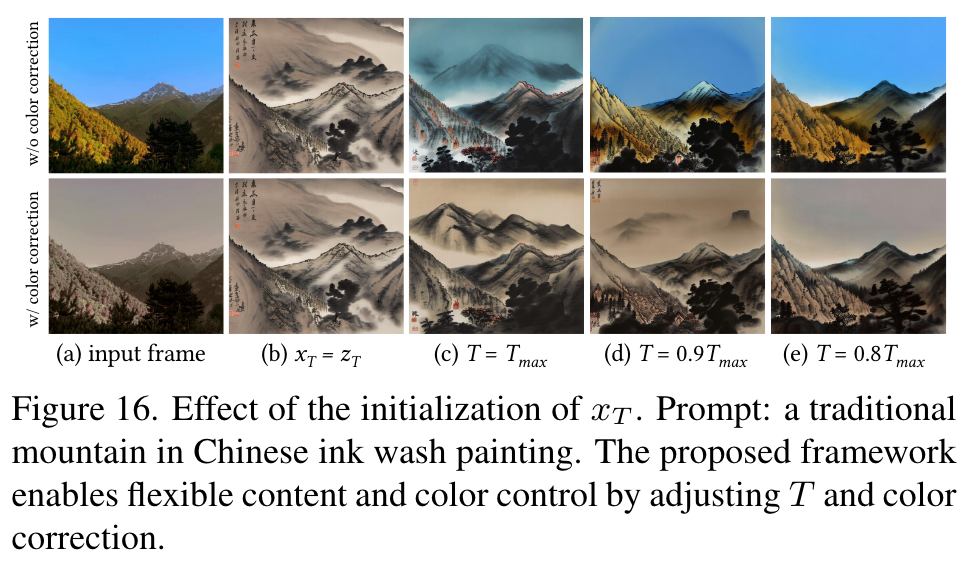

Flexible structure and color control

Rather than setting x_T to a Gaussian noise (Fig. 16(b)), we use a noisy latent version of the input frame to better preserve details (Fig. 16(c)). Users can adjust the value of T to balance content and prompt. (p. 8)

Limitations

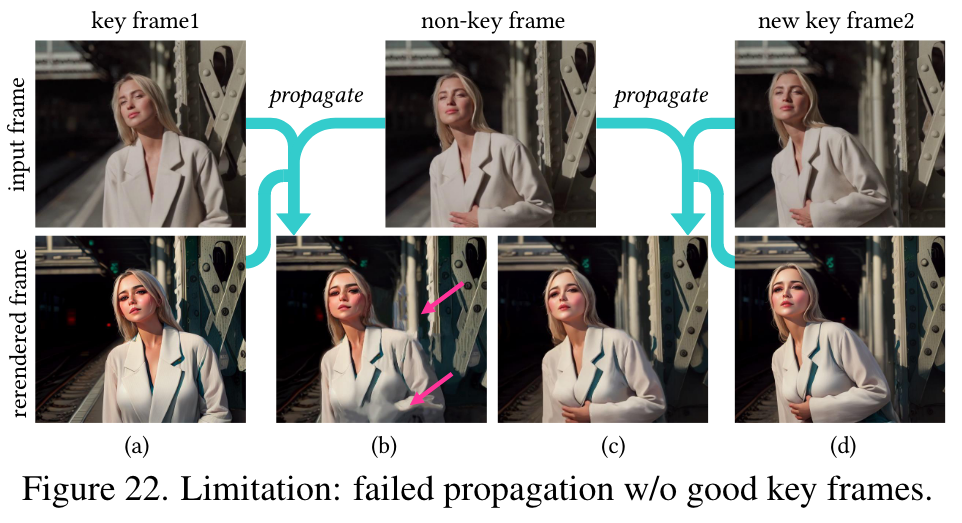

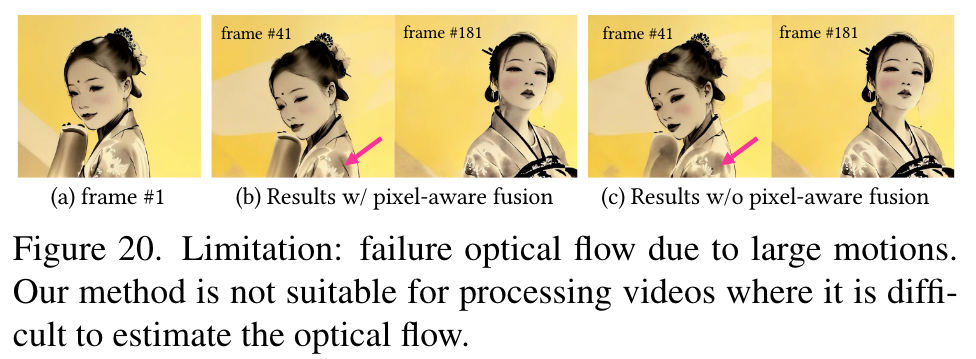

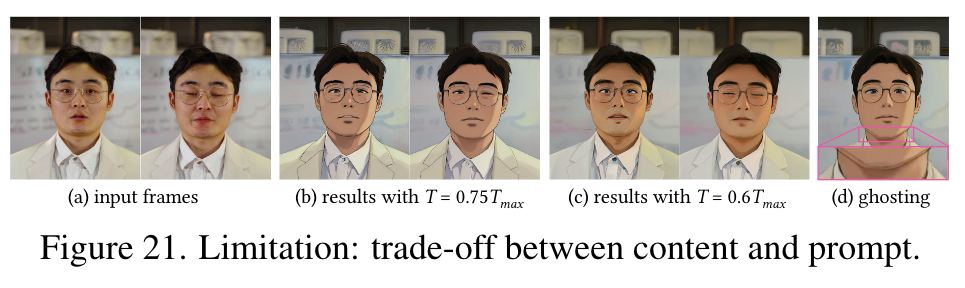

Figures 20-22 illustrate typical failure cases of our method. First our method relies on optical flow and therefore, inaccurate optical flow can lead to artifacts. In Fig. 20, our method can only preserve the embroidery if the crossframe correspondence is available. Otherwise, the proposed PA fusion will have no effect. Second, our method assumes the optical flow remains unchanged before and after translation, which may not hold true for significant appearance changes as in Fig. 21(b), where the resulting movement may be wrong. Although setting a smaller T can address this issue, it may compromise the desired styles. Meanwhile, the mismatches of the optical flow mean the mismatches in the translated key frames, which may lead to ghosting artifacts (Fig. 21(d)) after temporal-aware blending.

Also, we find that small details and subtle motions like accessories and eye movement cannot be well preserved during the translation.

Lastly, we uniformly sample the key frames, which may not optimal. Ideally, the key frames should contain all unique objects; otherwise, the propagation cannot create unseen content such as the hand in Fig. 22(b). One potential solution is user-interactive translation, where users can manually assign new key frames based on the previous results. (p. 10)