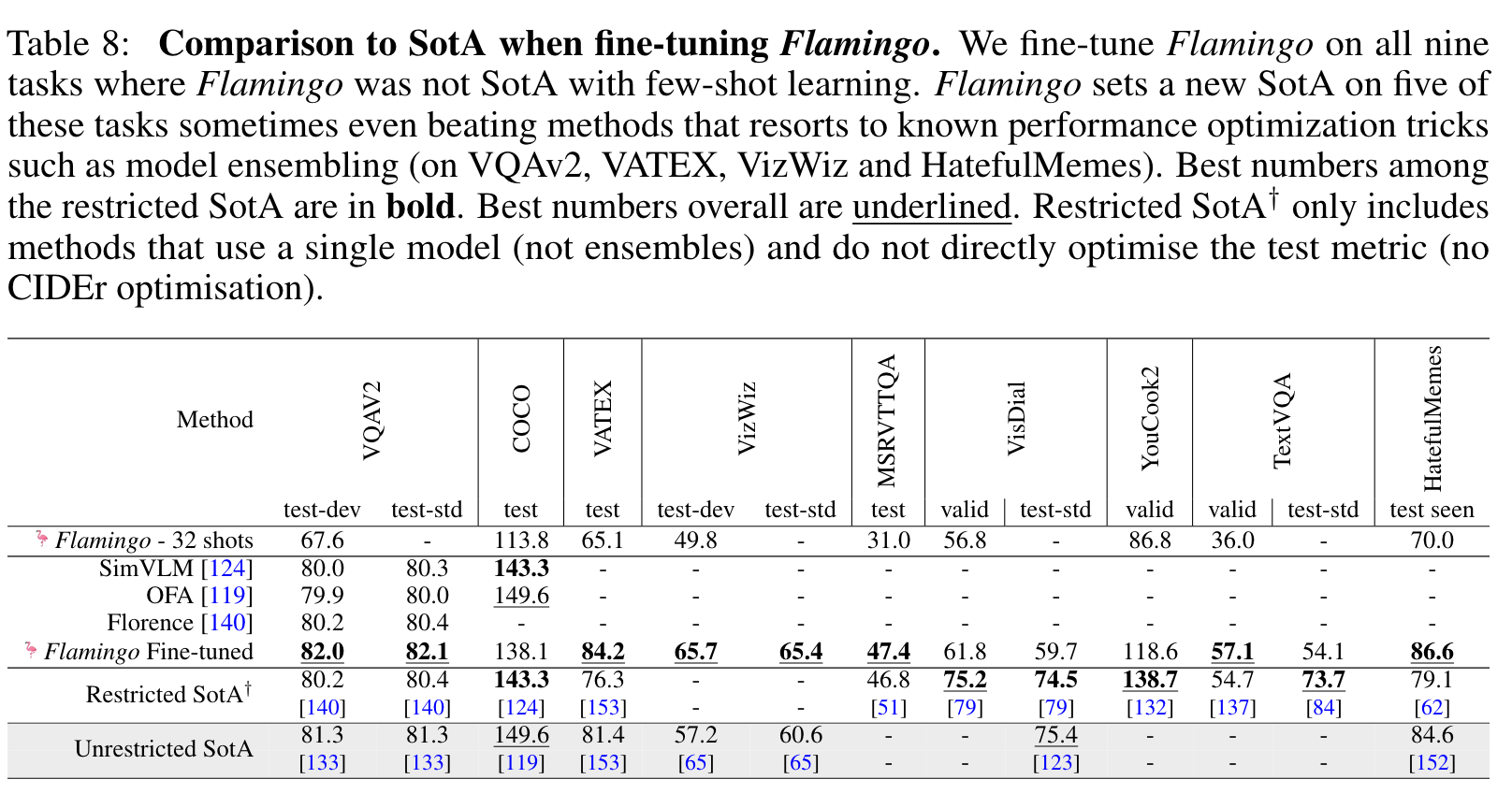

Flamingo a Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning

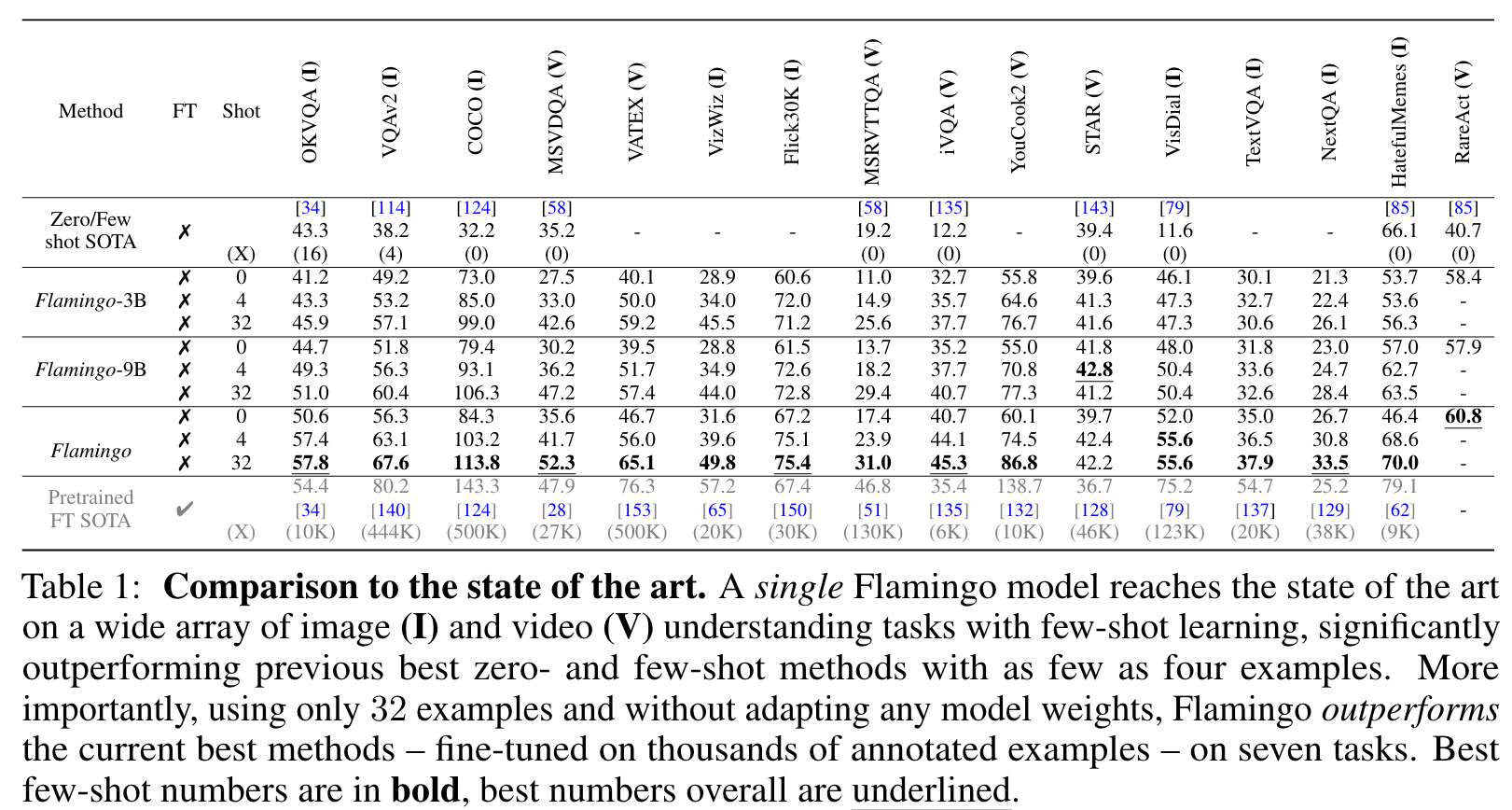

[llm transformer multimodal deep-learning flamingo vit perceiver zero-shot vqa align florence clip contrast-loss simvlm ofa This is my reading note for Flamingo: a Visual Language Model for Few-Shot Learning. This paper proposes to formulate vision language model vs text prediction task given existing text and visual. The model utilizes frozen visual encoder and LLM, and only fine tune the visual adapter (perceiver). The ablation study strongly against fine tune/retrain those components.

Introduction

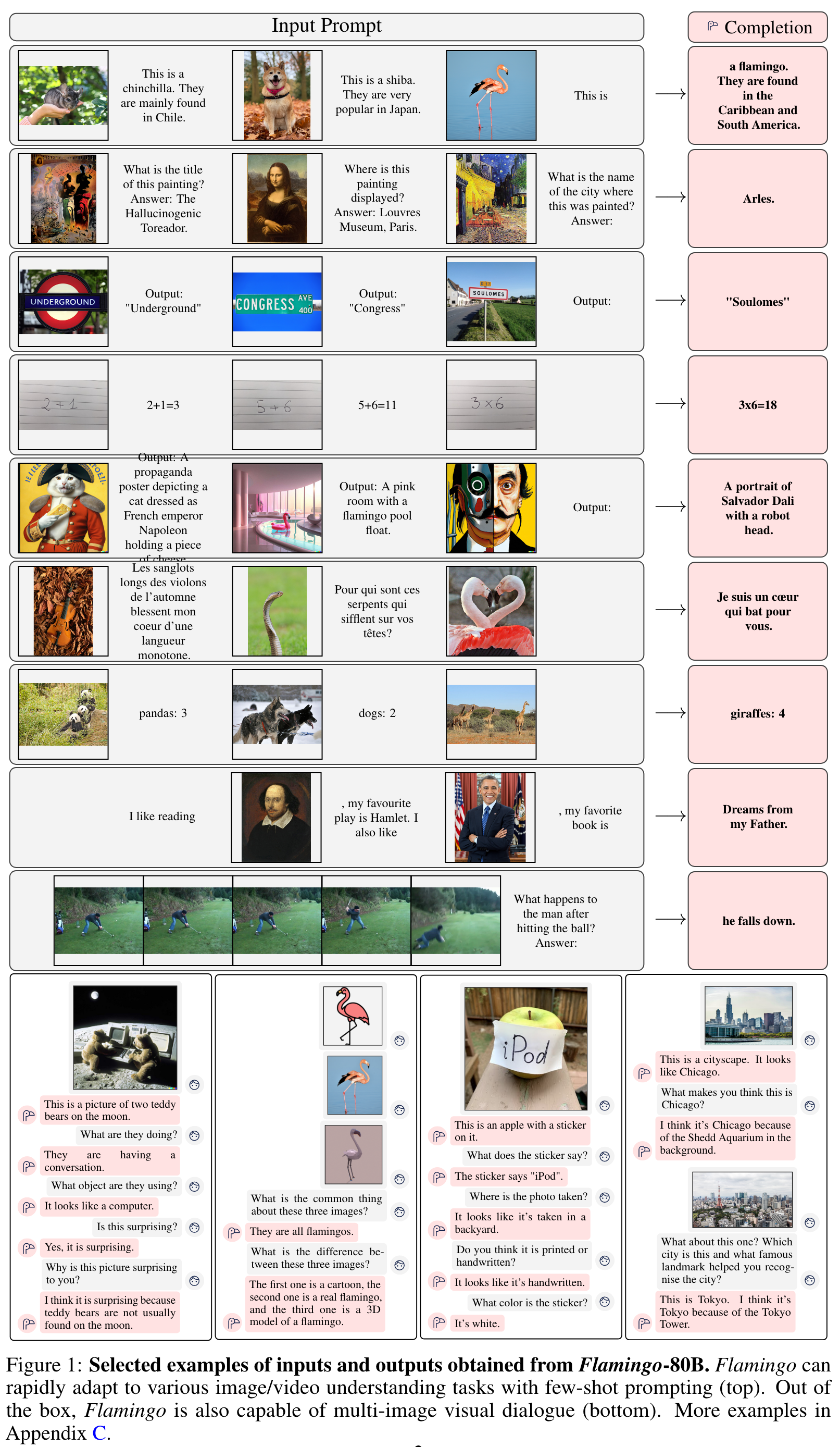

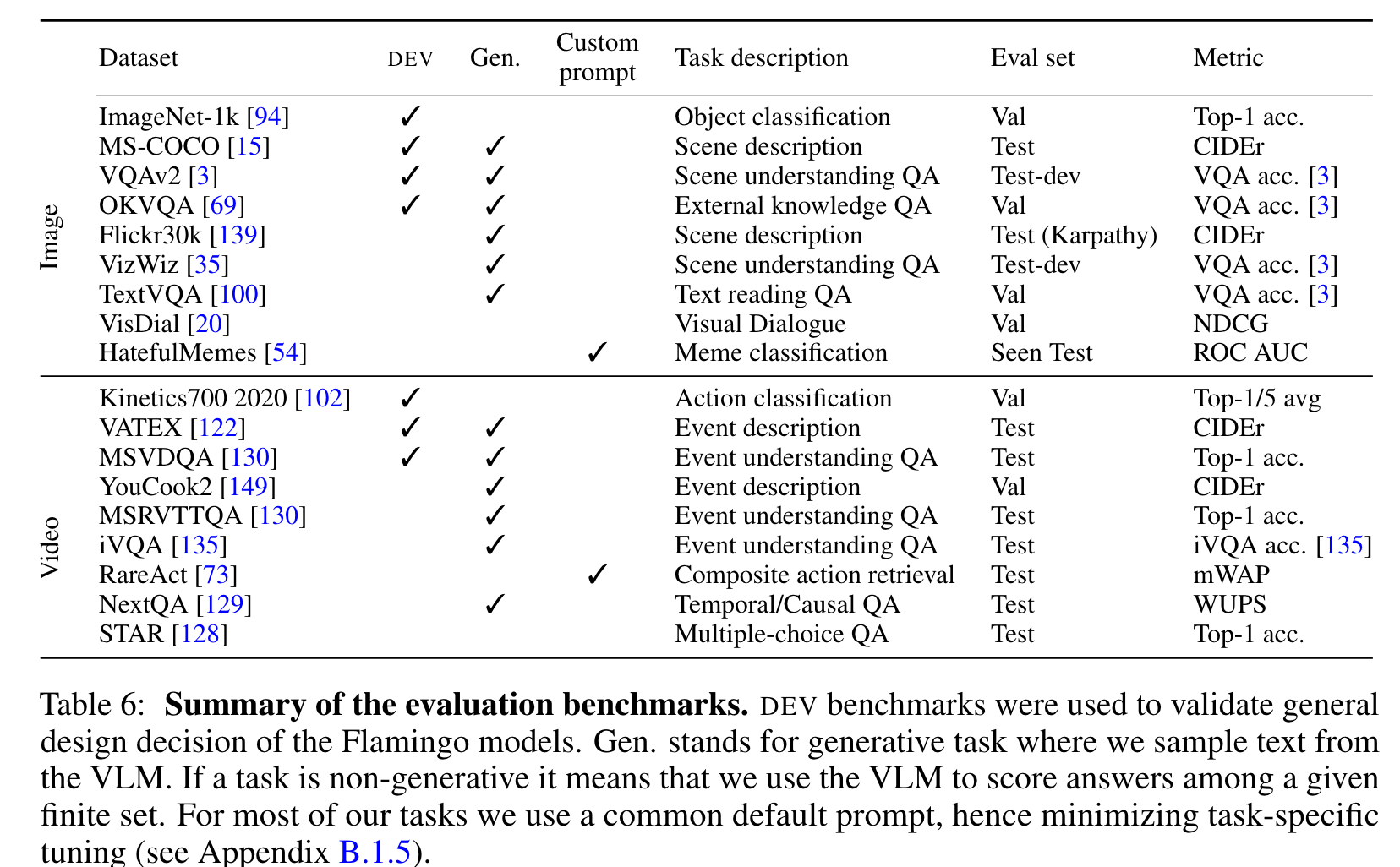

We show that the same can be done for image and video understanding tasks such as classification, captioning, or question-answering: these can be cast as text prediction problems with visual input conditioning. The difference from a LM is that the model must be able to ingest a multimodal prompt containing images and/or videos interleaved with text. Flamingo models have this capability—they are visually-conditioned autoregressive text generation models able to ingest a sequence of text tokens interleaved with images and/or videos, and produce text as output. (p. 3)

They are trained on a carefully chosen mixture of complementary large-scale multimodal data coming only from the web, without using any data annotated for machine learning purposes. (p. 4)

Proposed Method

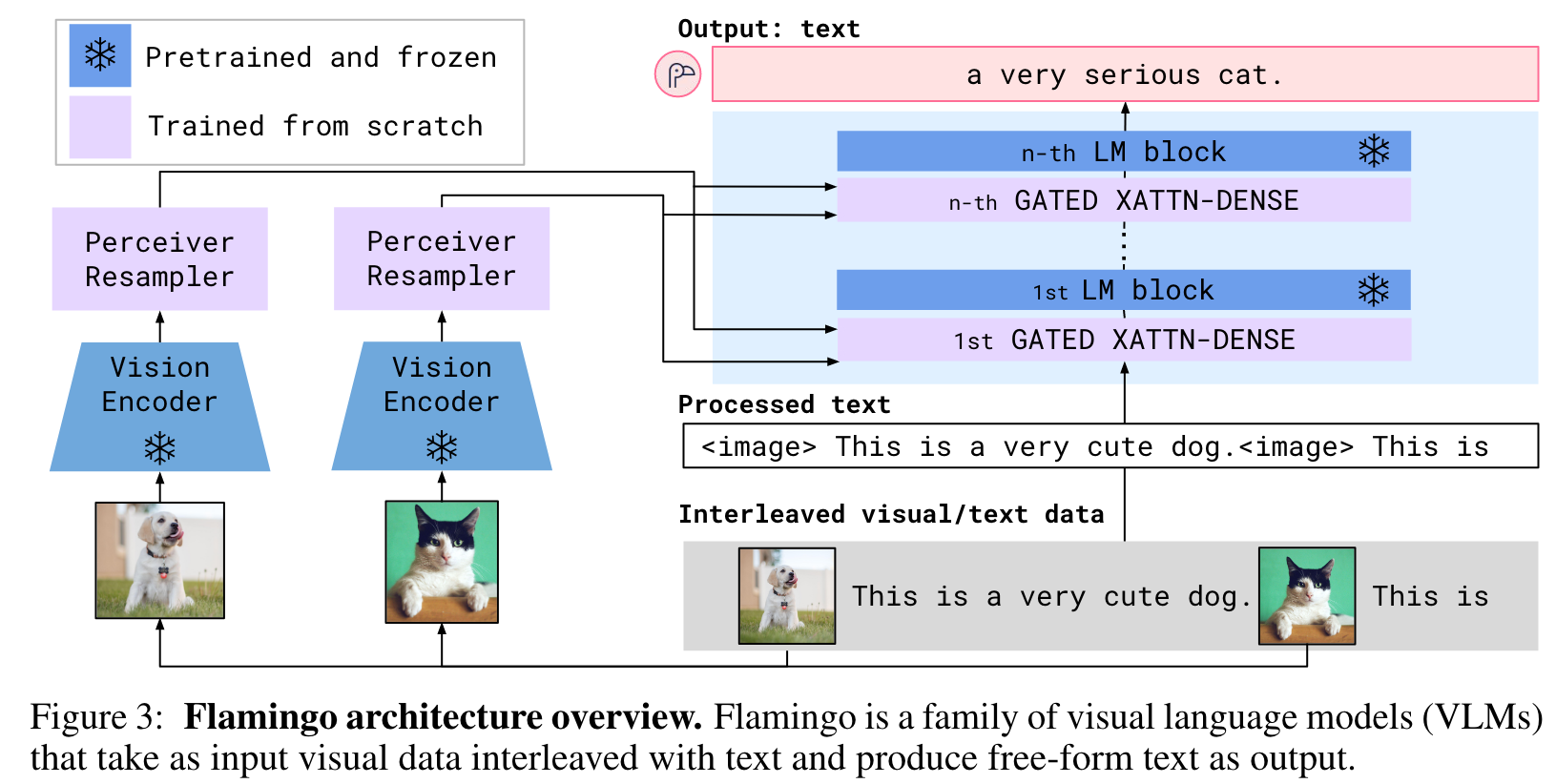

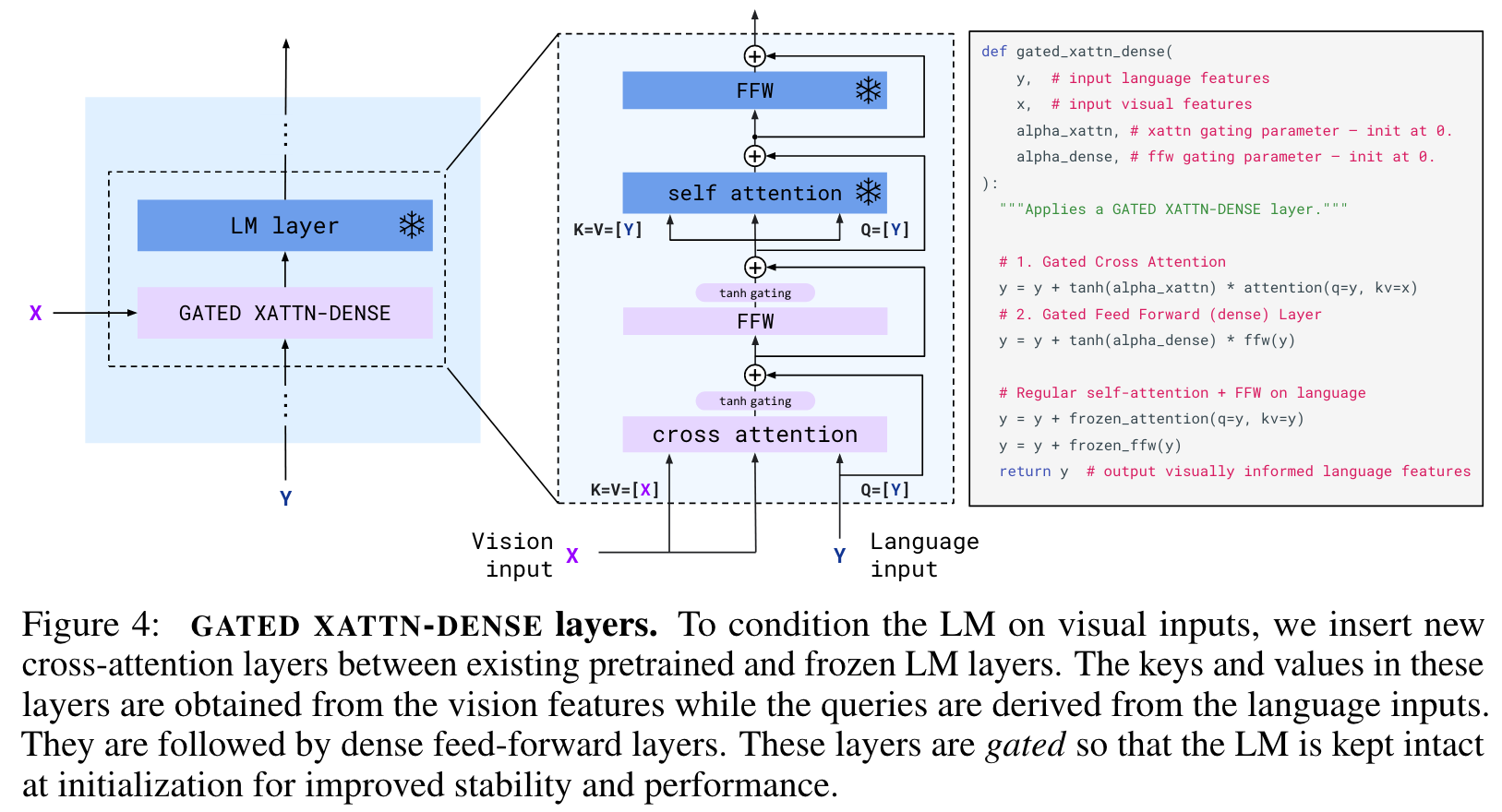

these visual tokens are used to condition the frozen LM using freshly initialised cross-attention layers (Section 2.2) that are interleaved between the pretrained LM layers. These new layers offer an expressive way for the LM to incorporate visual information for the next-token prediction task. (p. 4)

Visual processing and the Perceiver Resampler

Vision Encoder

from pixels to features. Our vision encoder is a pretrained and frozen NormalizerFree ResNet (NFNet) [10] – we use the F6 model. For video inputs, frames are sampled at 1 FPS and encoded independently to obtain a 3D spatio-temporal grid of features to which learned temporal embeddings are added. Features are then flattened to 1D before being fed to the Perceiver Resampler. (p. 5)

Perceiver Resampler

from varying-size large feature maps to few visual tokens. This module connects the vision encoder to the frozen language model as shown in Figure 3. It takes as input a variable number of image or video features from the vision encoder and produces a fixed number of visual outputs (64), reducing the computational complexity of the vision-text cross-attention. Similar to Perceiver [48] and DETR [13], we learn a predefined number of latent input queries which are fed to a Transformer and cross-attend to the visual features. (p. 5)

Multi-visual input support: per-image/video attention masking

Though the model only directly attends to a single image at a time, the dependency on all previous images remains via self-attention in the LM. This single-image cross-attention scheme importantly allows the model to seamlessly generalise to any number of visual inputs, regardless of how many are used during training. (p. 6)

Training on a mixture of vision and language datasets

M3W: Interleaved image and text dataset

For this purpose, we collect the MultiModal MassiveWeb (M3W) dataset. We extract both text and images from the HTML of approximately 43 million webpages, determining the positions of images relative to the text based on the relative positions of the text and image elements in the Document Object Model (DOM). An example is then constructed by inserting <image> tags in plain text at the locations of the images on the page, and inserting a special <EOC> (end of chunk) token (added to the vocabulary and learnt) prior to any image and at the end of the document. From each document, we sample a random subsequence of 𝐿 = 256 tokens and take up to the first 𝑁 = 5 images included in the sampled sequence. (p. 6)

Pairs of image/video and text

For our image and text pairs we first leverage the ALIGN [50] dataset, composed of 1.8 billion images paired with alt-text. To complement this dataset, we collect our own dataset of image and text pairs targeting better quality and longer descriptions: LTIP (Long Text & Image Pairs) which consists of 312 million image and text pairs. We also collect a similar dataset but with videos instead of still images: VTP (Video & Text Pairs) consists of 27 million short videos (approximately 22 seconds on average) paired with sentence descriptions. We align the syntax of paired datasets with the syntax of M3W by prepending <image> and appending <EOC> to each training caption (p. 6)

Multi-objective training and optimisation strategy

We train our models by minimizing a weighted sum of per-dataset expected negative log-likelihoods of text, given the visual inputs: (p. 6)

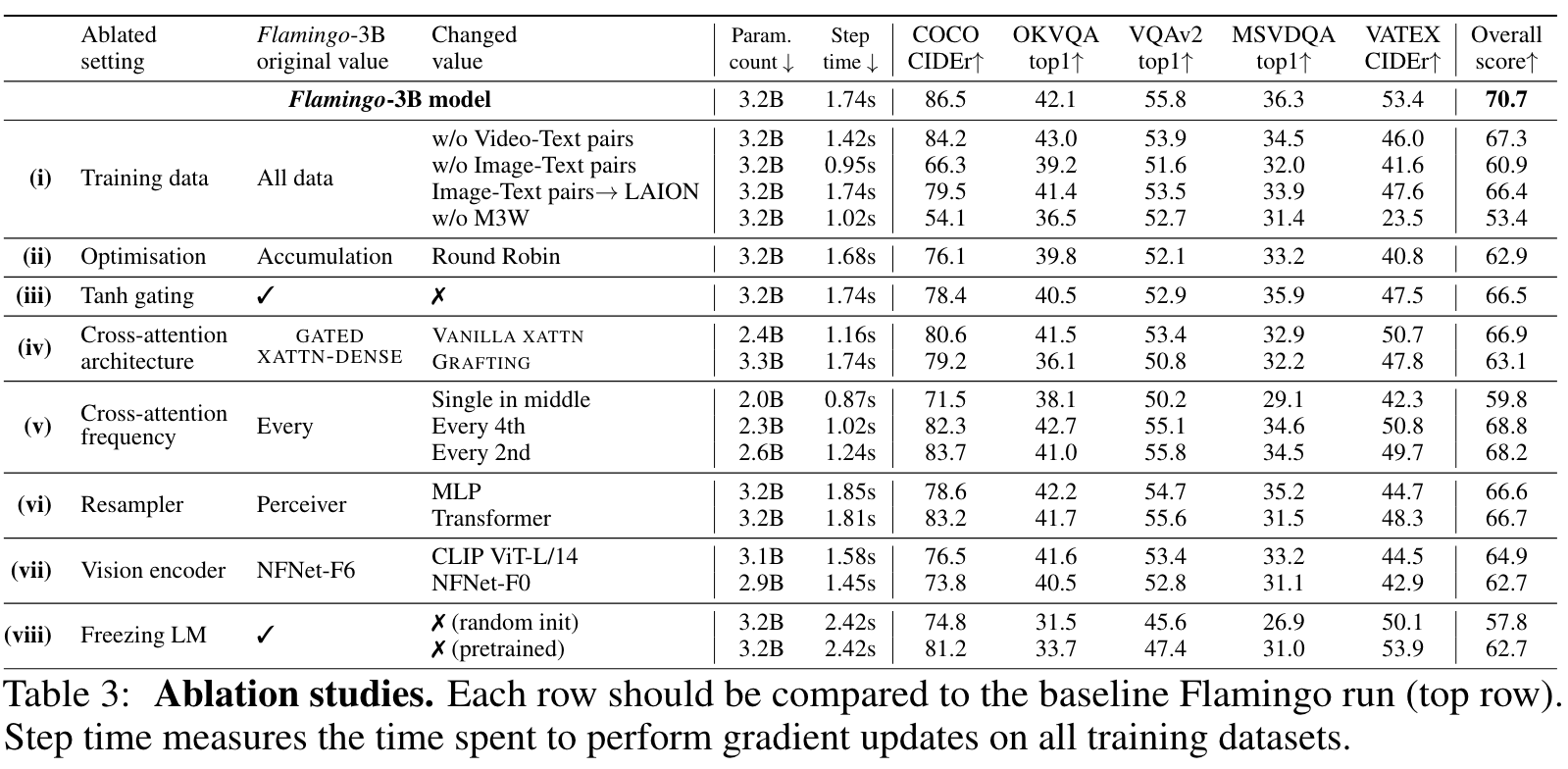

Tuning the per-dataset weights 𝜆_𝑚 is key to performance. We accumulate gradients over all datasets, which we found outperforms a “round-robin” approach [17]. (p. 6)

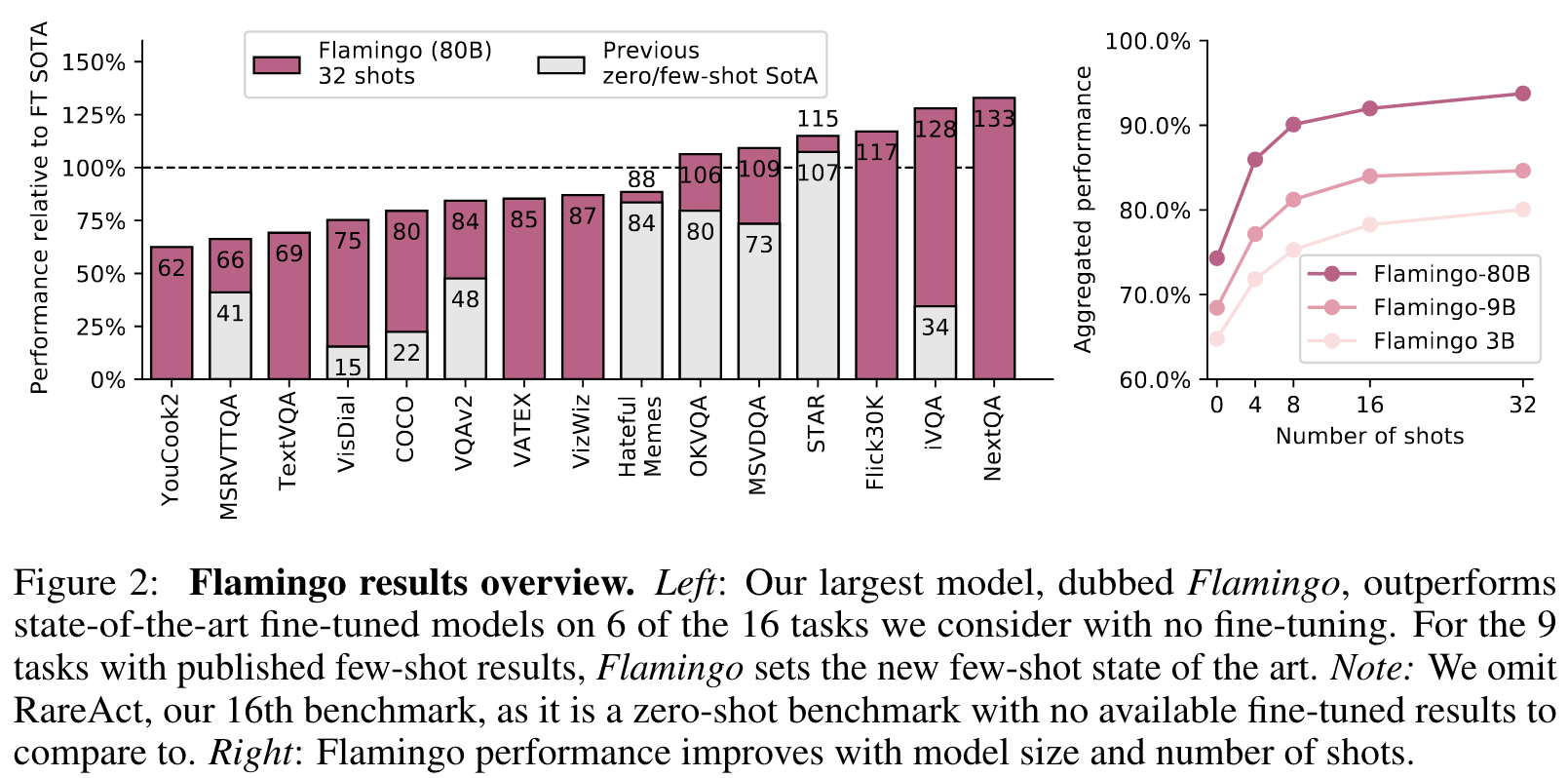

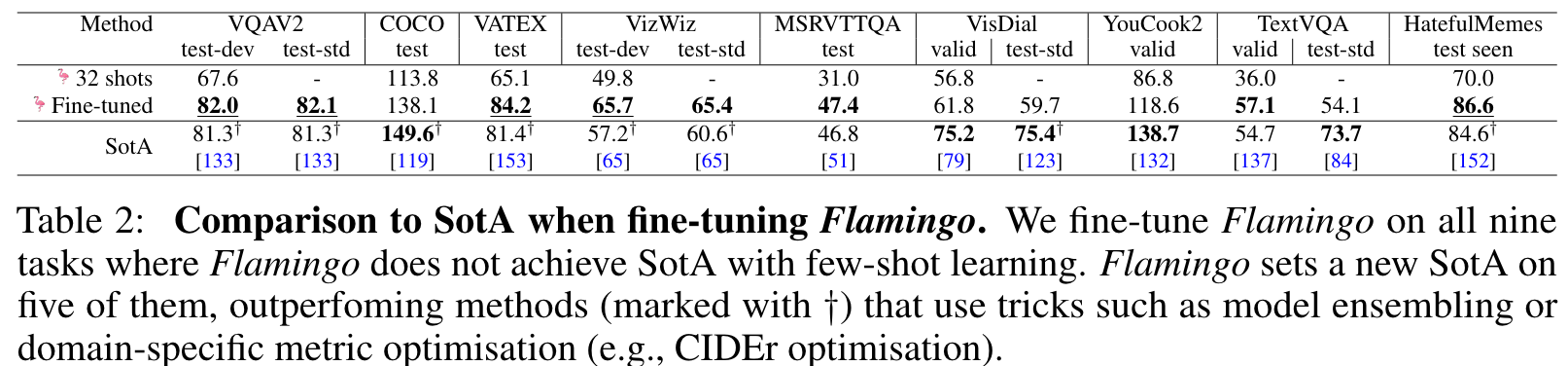

Experiment

Limitations

First, our models build on pretrained LMs, and as a side effect, directly inherit their weaknesses. For example, LM priors are generally helpful, but may play a role in occasional hallucinations and ungrounded guesses. Furthermore, LMs generalise poorly to sequences longer than the training ones. They also suffer from poor sample efficiency during training. (p. 10)

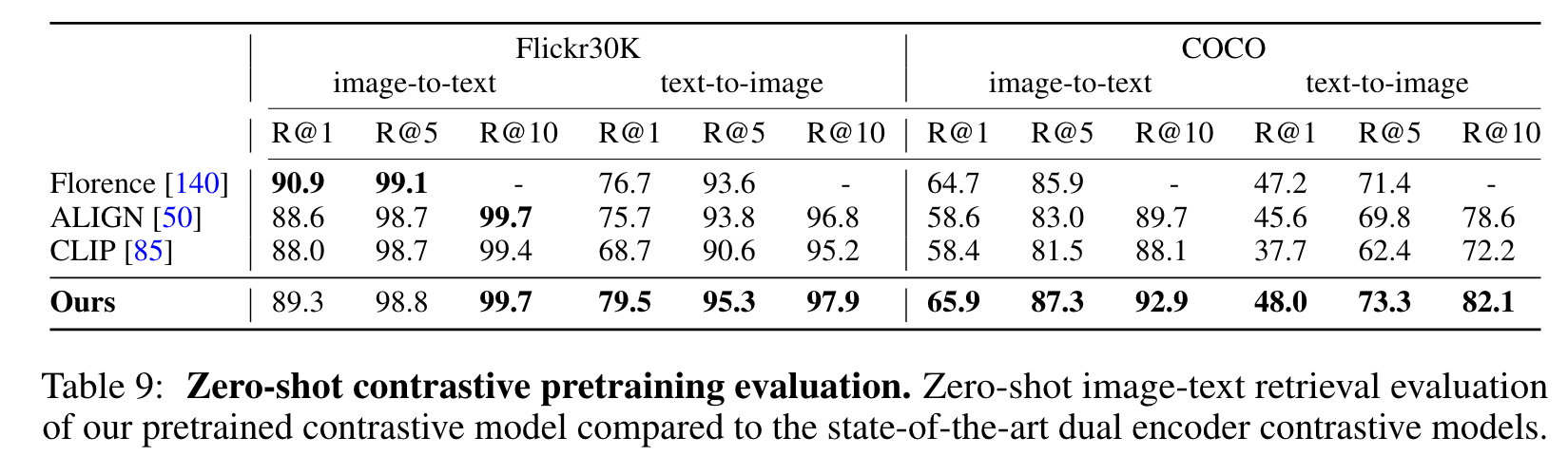

Second, the classification performance of Flamingo lags behind that of state-of-the-art contrastive models [82, 85]. These models directly optimize for text-image retrieval, of which classification is a special case. (p. 10)

Although our visual language models have important advantages over contrastive models (e.g., few-shot learning and open-ended generation capabilities), their performance lags behind that of contrastive models on classification tasks. We believe this is because the contrastive training objective directly optimizes for text-image retrieval, and in practice, the evaluation procedure for classification can be thought of as a special case of image-to-text retrieval [85]. (p. 38)

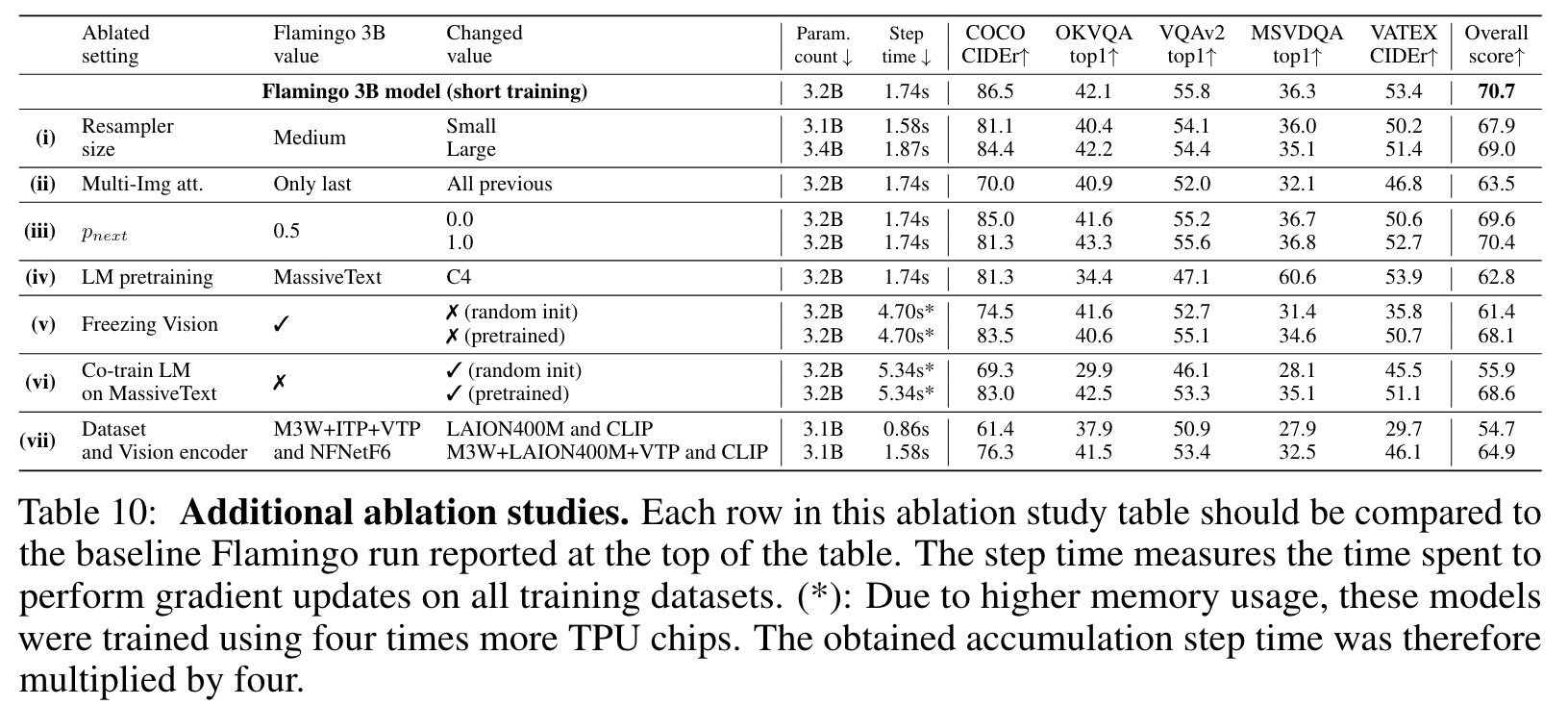

Ablation

Effect of how many images are cross-attended to

We can see that the single image case leads to significantly better results (7.2% better in the overall score). One potential explanation is that when attending to all previous images, there is no explicit way of disambiguating between different images in the cross-attention inputs. (p. 35)

Freezing the vision encoder

We ablate in (v) of Table 10 this freezing decision by training the Vision Encoder weights either from scratch or initialized with the contrastive vision-language task. If trained from scratch, we observe that the performance decreases by a large margin of −9.3%. Starting from pretrained weights still leads to a drop in performance of −2.6% while also increasing the compute cost of the training. (p. 36)

Alternative to freezing the LM by co-training on MassiveText

In both cases, the overall scores are worse than our baseline which starts from the language model, pretrained on MassiveText, and is kept frozen throughout training. This indicates that the strategy of freezing the language model to avoid catastrophic forgetting is beneficial. (p. 36)

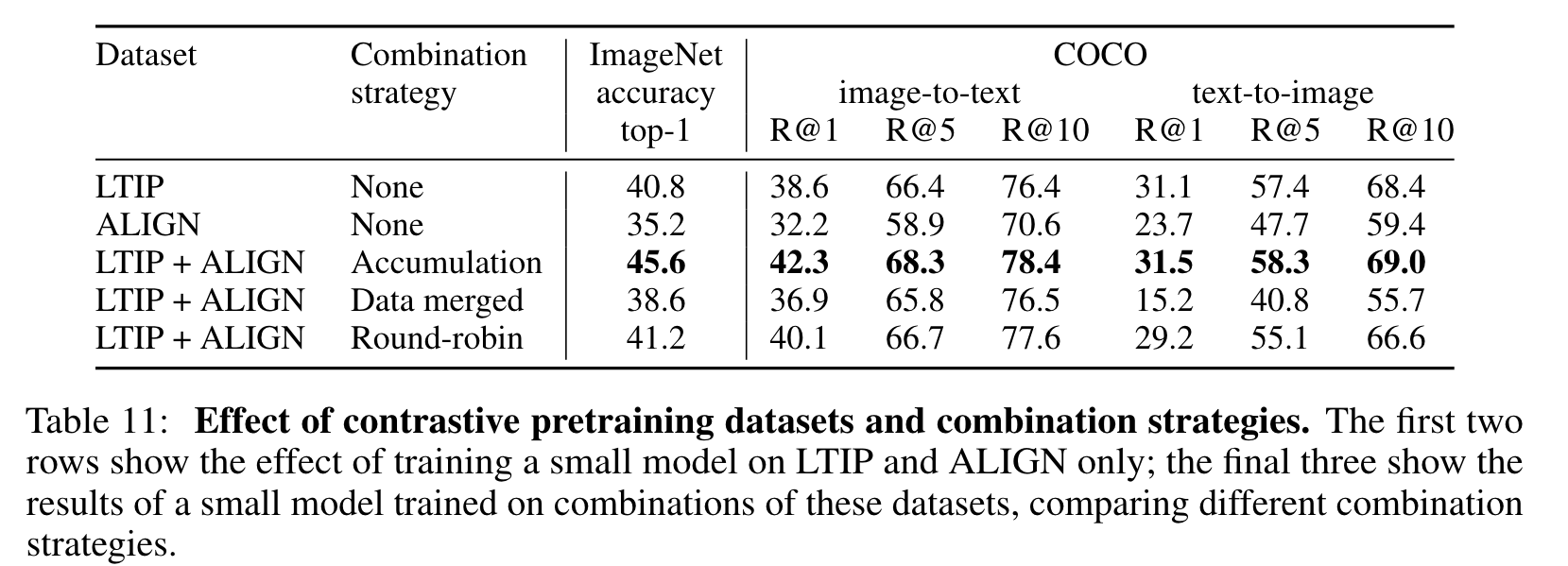

Dataset mixing strategies for the contrastive pretraining

Despite being a smaller dataset ALIGN by a factor of 6, a contrastive model trained on only LTIP outperforms one trained only on ALIGN on our evaluation metrics, suggesting that dataset quality may be more important than scale in the regimes in which we operate. model trained on both ALIGN and LTIP outperforms those trained on the two datasets individually and that how the datasets are combined is important (p. 37)

- Data merged: Batches are constructed by merging examples from each dataset into one batch.

- Round-robin: We alternate batches of each dataset, updating the parameters on each batch.

- Accumulation: We compute a gradient on a batch from each dataset. These gradients are then weighted and summed and use to update the parameters. (p. 37)