InstructBLIP Towards General-purpose Vision-Language Models with Instruction Tuning

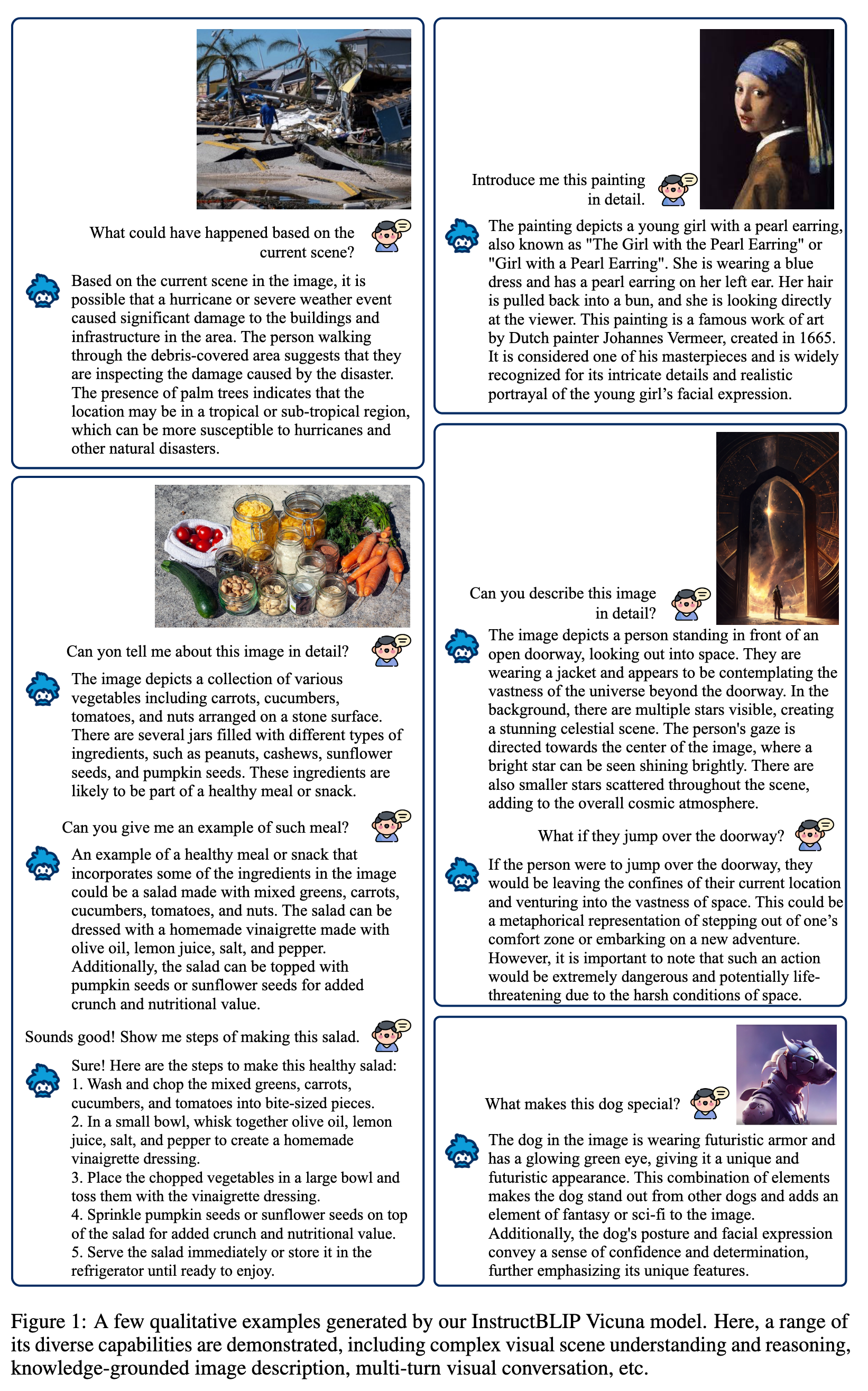

[vicuna multimodal llm blip query-transformer llama qformer deep-learning llava flat-t5 This is my reading note for InstructBLIP: Towards General-purpose Vision-Language Models with Instruction Tuning. The paper proposes an extension of blip 2 with institution tuning. This has dramatically improved the performance to unseen tasks. The method is based on query transformer, but adding the tokens from the instruction to guide the feature extraction.

Introduction

Additionally, we introduce an instruction-aware Query Transformer, which extracts informative features tailored to the given instruction. (p. 1)

By finetuning a large language model (LLM) on a wide range of tasks described by natural language instructions, instruction tuning enables the model to follow arbitrary instructions. Recently, instruction-tuned LLMs have also been leveraged for vision-language tasks (p. 1)

Most previous work can be grouped into two approaches.

- The first approach, multitask learning [6, 27], formulates various vision-language tasks into the same input-output format. However, we empirically find multitask learning without instructions (Table 4) does not generalize well to unseen datasets and tasks. The (p. 1)

- second approach [20, 4] extends a pre-trained LLM with additional visual components, and trains the visual components with image caption data. Nevertheless, such data are too limited to allow broad generalization to vision-language tasks that require more than visual descriptions. (p. 3)

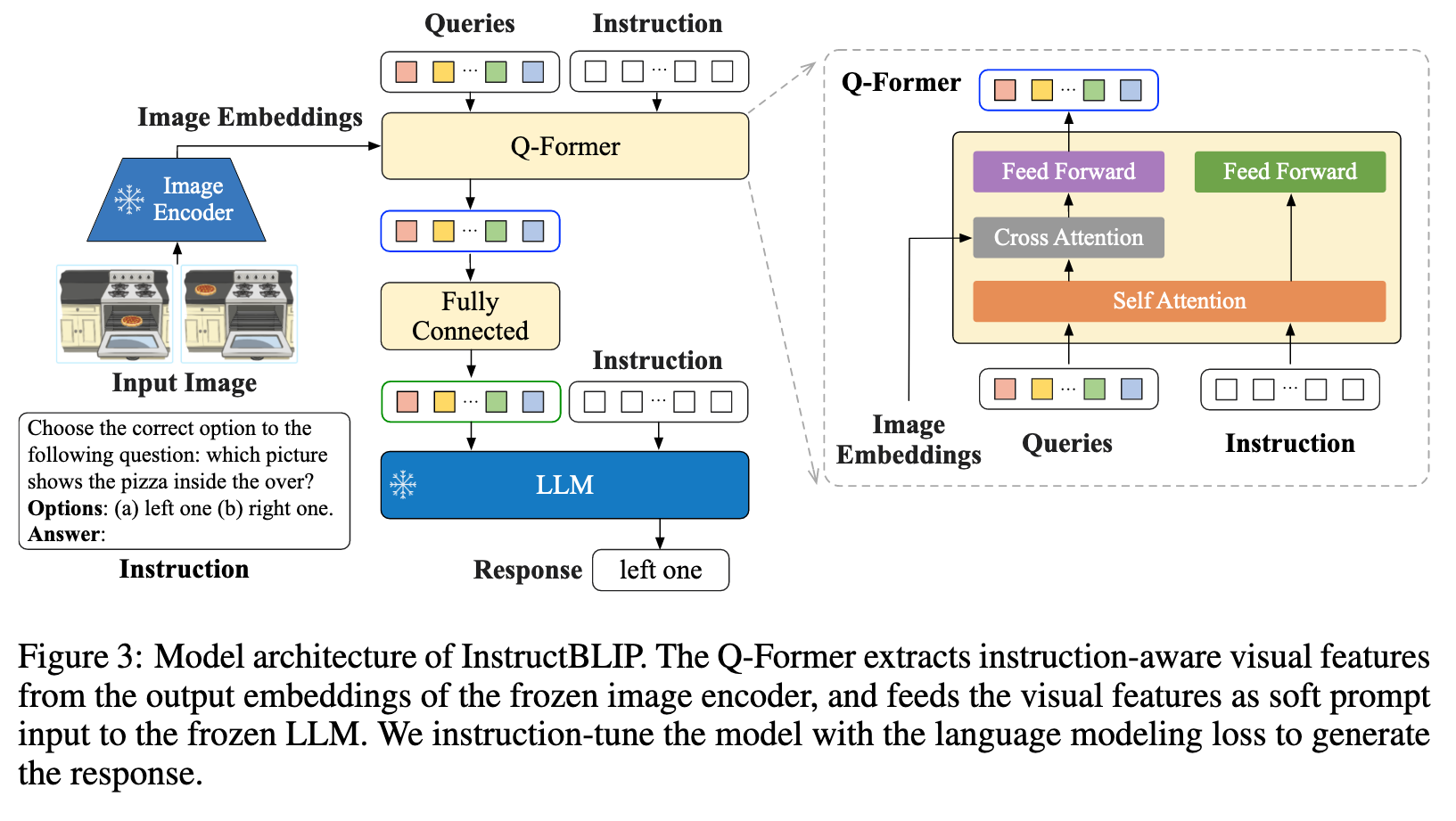

InstructBLIP uses a diverse set of instruction data to train a multimodal LLM. Specifically, we initialize training with a pre-trained BLIP-2 model consisting of an image encoder, an LLM, and a Query Transformer (Q-Former) to bridge the two. During instruction tuning, we finetune the Q-Former while keeping the image encoder and LLM frozen. (p. 3)

Related Work

Instruction tuning aims to teach language models to follow natural language instructions, which has been shown to improve their generalization performance to unseen tasks. Some methods collect instruction tuning data by converting existing NLP datasets into instruction format using templates [46, 7, 35, 45]. Others use LLMs (e.g., GPT-3 [5]) to generate instruction data [2, 13, 44, 40] with improved diversity. (p. 9)

Instruction-tuned LLMs have been adapted for vision-to-language generation tasks by injecting visual information to the LLMs. BLIP-2 [20] uses frozen FlanT5 models, and trains a Q-Former to extract visual features as input to the LLMs. MiniGPT-4 [52] uses the same pretrained visual encoder and Q-Former from BLIP-2, but uses Vicuna [2] as the LLM and performs training using ChatGPT [1]-generated image captions longer than the BLIP-2 training data. LLaVA [25] directly projects the output of a visual encoder as input to a LLaMA/Vinuca LLM, and finetunes the LLM on vision-language conversational data generated by GPT-4 [33]. mPLUG-owl [50] performs low-rank adaption [14] to a LLaMA [41] model using both text instruction data and vision-language instruction data from LLaVA. A separate work is MultiInstruct [48], which performs vision-language instruction tuning without a pretrained LLM, leading to less competitive performance. (p. 9)

Vision-Language Instruction Tuning

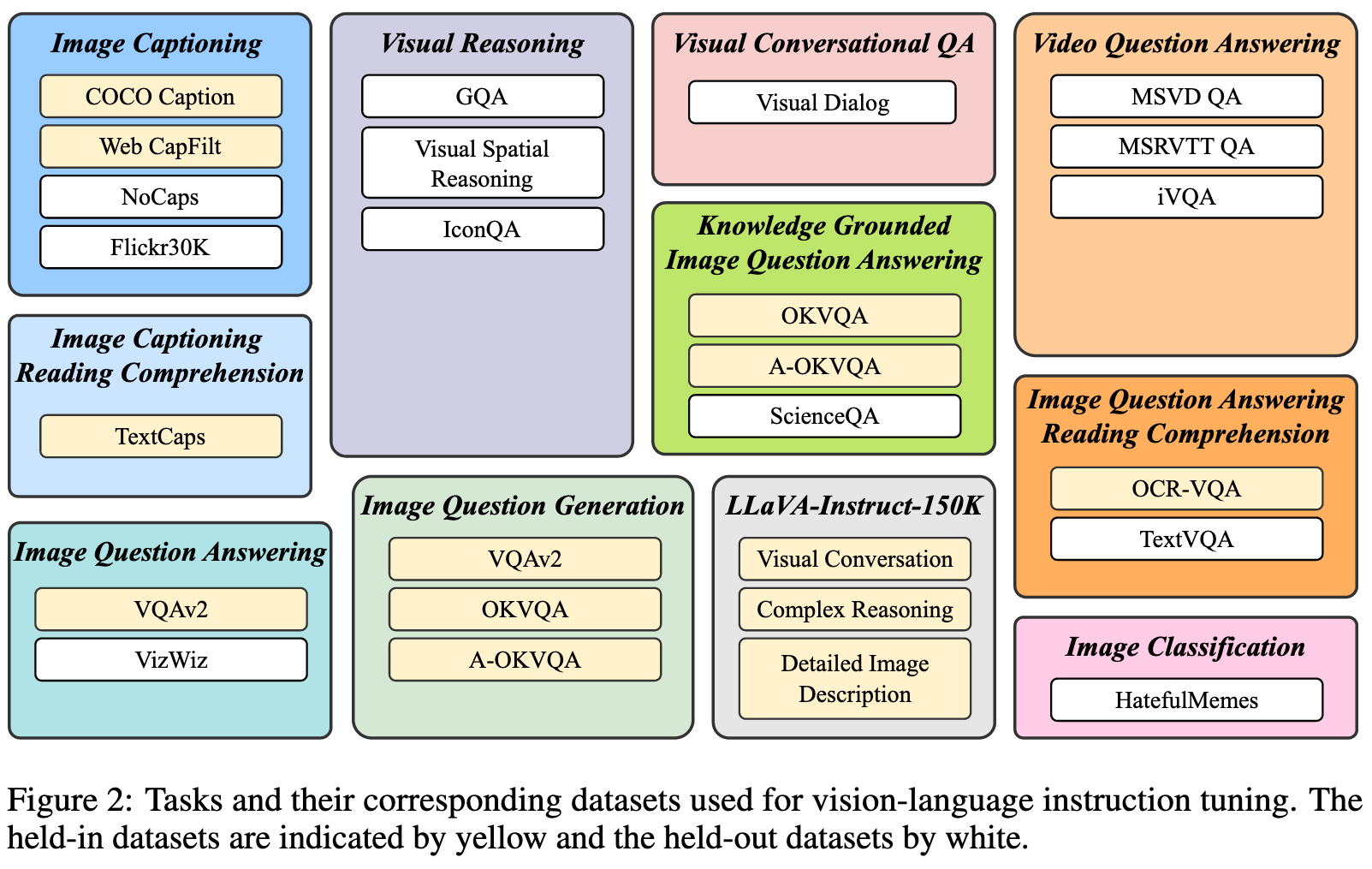

Tasks and Datasets

To ensure the diversity of instruction tuning data while considering their accessibility, we gather comprehensive set of publicly available vision-language datasets, and transform them into the instruction tuning format. (p. 3)

For every task, we meticulously craft 10 to 15 distinct instruction templates in natural language. These templates serve as the foundation for constructing instruction tuning data, which articulates the task and the objective. For public datasets inherently favoring short responses, we use terms such as short and briefly into some of their corresponding instruction templates to reduce the risk of the model overfitting to always generating short outputs. (p. 3)

Instruction-aware Visual Feature Extraction

Existing zero-shot image-to-text generation methods, including BLIP-2, take an instruction-agnostic approach when extracting visual features. That results in a set of static visual representations being fed into the LLM, regardless of the task. In contrast, an instruction-aware vision model can adapt to the task instruction and produce visual representations most conducive to the task at hand. This is clearly advantageous if we expect the task instructions to vary considerably for the same input image. (p. 4)

Similarly to BLIP-2 [20], InstructBLIP utilizes a Query Transformer, or Q-Former, to extract visual features from a frozen image encoder. The input to the Q-Former contains a set of K learnable query embeddings, which interact with the image encoder’s output through cross attention. The output of the Q-Former consists of K encoded visual vectors, one per query embedding, which then go through a linear projection and are fed to the frozen LLM. As in BLIP-2, the Q-Former is pretrained in two stages using image-caption data before instruction tuning. The first stage pretrains the Q-Former with the frozen image encoder for vision-language representation learning. The second stage adapts the output of Q-Former as soft visual prompts for text generation with a frozen LLM . After pretraining, we finetune the Q-Former with instruction tuning, where the LLM receives as input the visual encodings from the Q-Former and the task instruction. (p. 5)

Extending BLIP-2, InstructBLIP proposes an instruction-aware Q-former module, which takes in the instruction text tokens as additional input. The instruction interacts with the query embeddings through self-attention layers of the Q-Former, and encourages the extraction of task-relevant image features. As a result, the LLM receives visual information conducive to instruction following. (p. 5)

Balancing Training Datasets

To mitigate the problem, we propose to sample datasets with probabilities proportional to the square root of their sizes, or the numbers of training samples. (p. 5)

Inference Methods

During inference time, we adopt two slightly different generation approaches for evaluation on different datasets. For the majority of datasets, such as image captioning and open-ended VQA, the instruction-tuned model is directly prompted to generate responses, which are subsequently compared to the ground truth to calculate metrics. On the other hand, for classification and multi-choice VQA tasks, we employ a vocabulary ranking method following previous works [46, 22, 21]. Specifically, we still prompt the model to generate answers, but restrict its vocabulary to a list of candidates. Then, we calculate log-likelihood for each candidate and select the one with the highest value as the final prediction (p. 5)

Implementation Details

FlanT5 [7] is an instruction-tuned model based on the encoder-decoder Transformer T5 [34]. Vicuna [2], on the other hand, is a recently released decoder-only Transformer instruction-tuned from LLaMA [41]. During vision-language instruction tuning, we initialize the model from pre-trained BLIP-2 checkpoints, and only finetune the parameters of Q-Former while keeping both the image encoder and the LLM frozen (p. 6)

All models are instruction-tuned with a maximum of 60K steps and we validate model’s performance every 3K steps. For each model, a single optimal checkpoint is selected and used for evaluations on all datasets. We employ a batch size of 192, 128, and 64 for the 3B, 7B, and 11/13B models, respectively. The AdamW [26] optimizer is used, with β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999, and a weight decay of 0.05. Additionally, we apply a linear warmup of the learning rate during the initial 1,000 steps, increasing from 10−8 to 10−5, followed by a cosine decay with a minimum learning rate of 0. All models are trained utilizing 16 Nvidia A100 (40G) GPUs and are completed within 1.5 days. (p. 6)

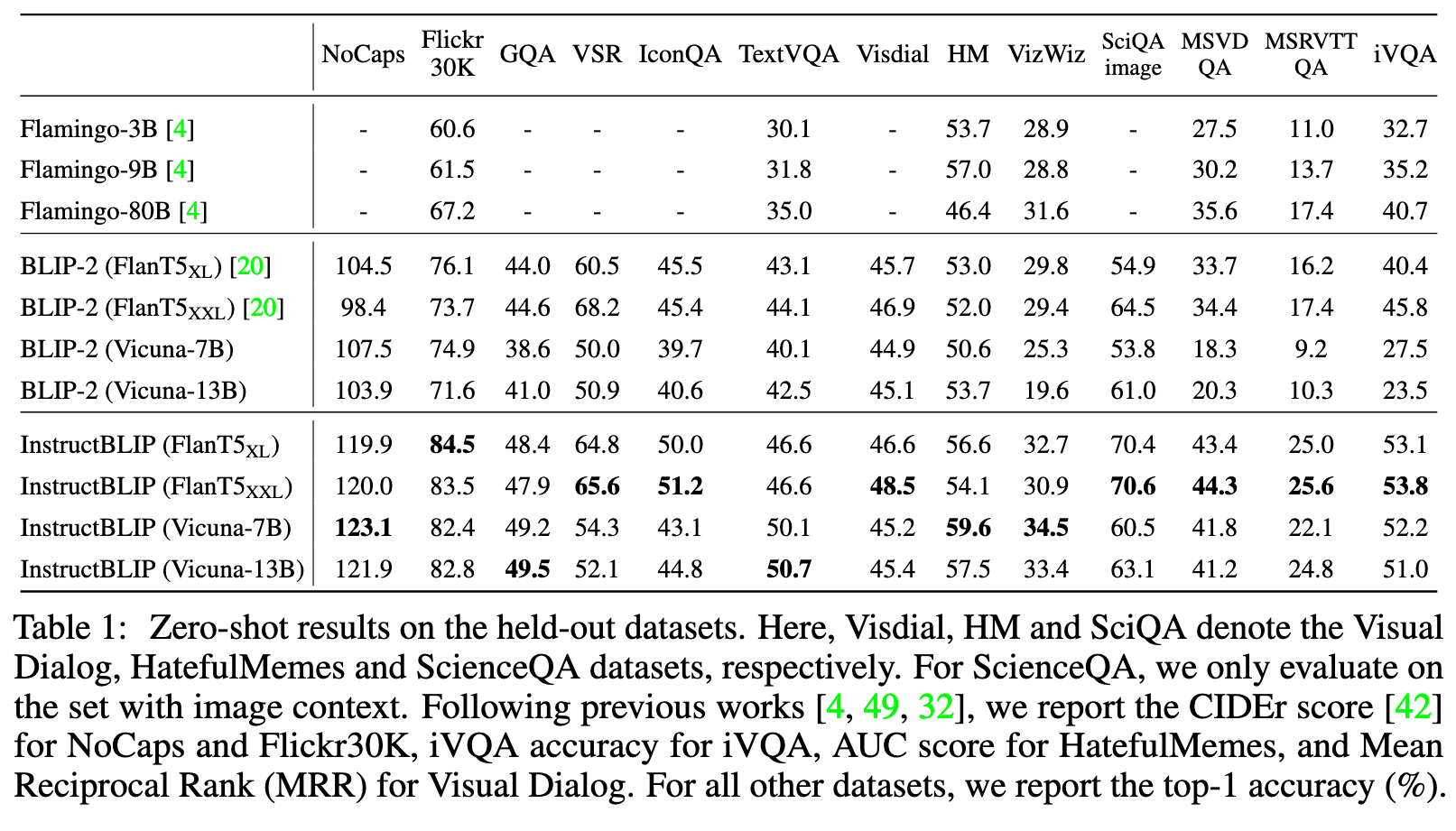

Experiment

In Appendix B, we qualitatively compare InstructBLIP with concurrent multimodal models (GPT- 4 [33], LLaVA [25], MiniGPT-4 [52]). Although all models are capable of generating long-form responses, InstructBLIP’s outputs generally contains more proper visual details and exhibits logically coherent reasoning steps. (p. 7)

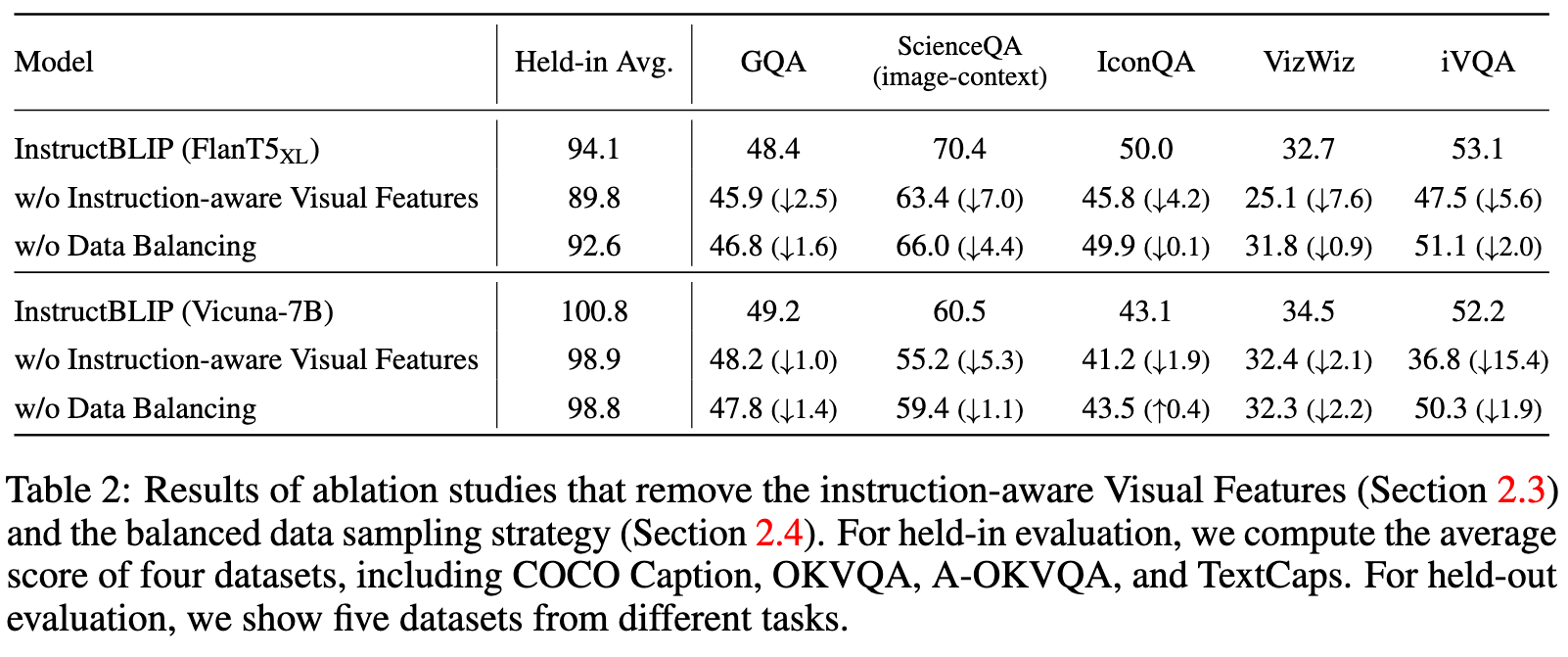

Ablation Study on Instruction Tuning Techniques

As illustrated in Table 2, the removal of instruction awareness in visual features downgrades performance significantly across all datasets. The performance drop is more severe in datasets that involve spatial visual reasoning (e.g., ScienceQA) or temporal visual reasoning (e.g., iVQA), where the instruction input to the Q-Former can guide visual features to attend to informative image regions. (p. 7)

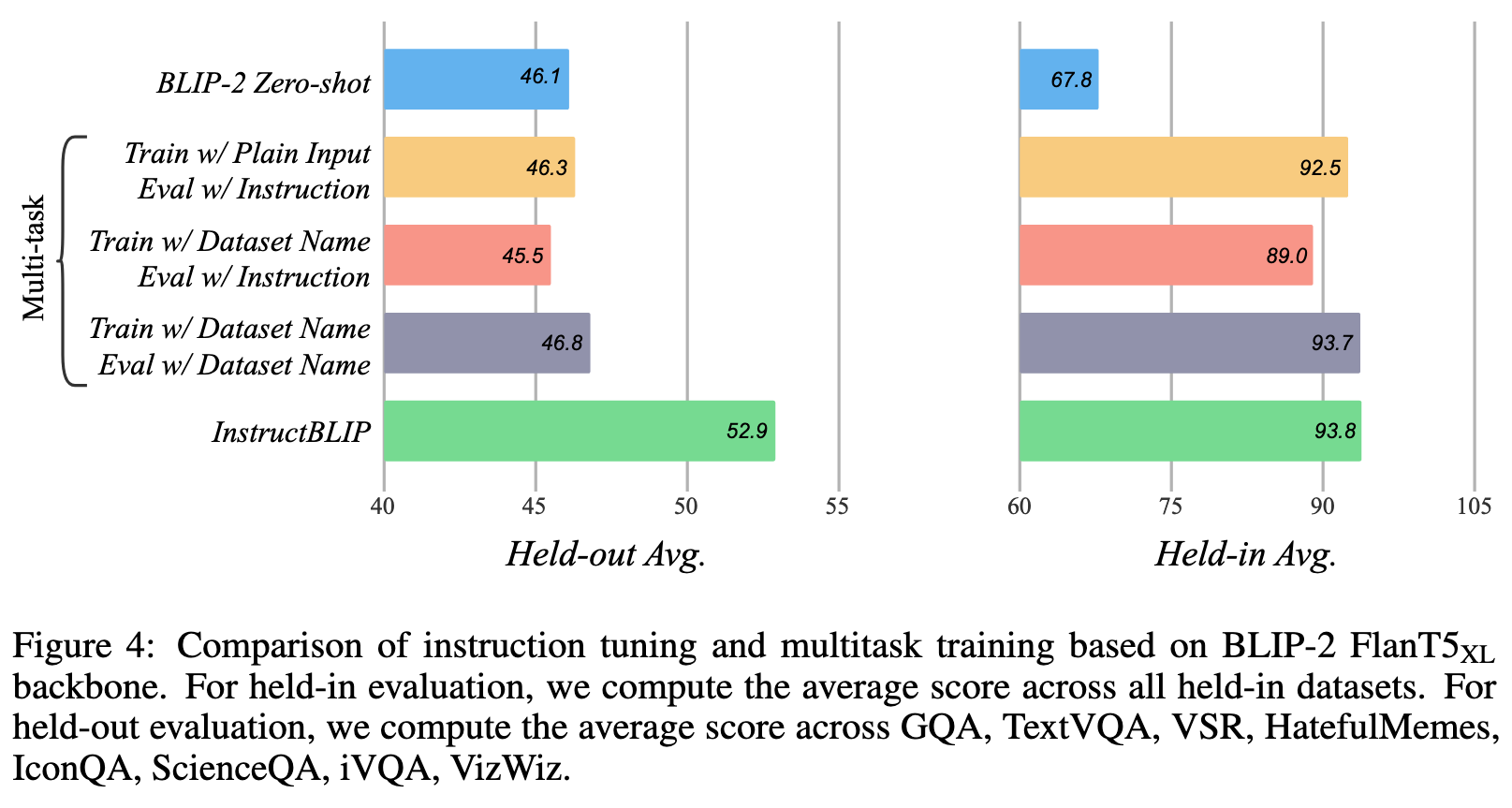

Instruction Tuning vs. Multitask Learning

Overall, we can conclude two insights from the results. Firstly, instruction tuning and multitask learning exhibit similar performance on the held-in datasets. This suggests that the model can fit these two different input patterns comparably well, as long as it has been trained with such data. On the other hand, instruction tuning yields a significant improvement over multitask learning on unseen held-out datasets, whereas multitask learning still performs on par with the original BLIP-2. This indicates that instruction tuning is the key to enhance the model’s zero-shot generalization ability. (p. 8)

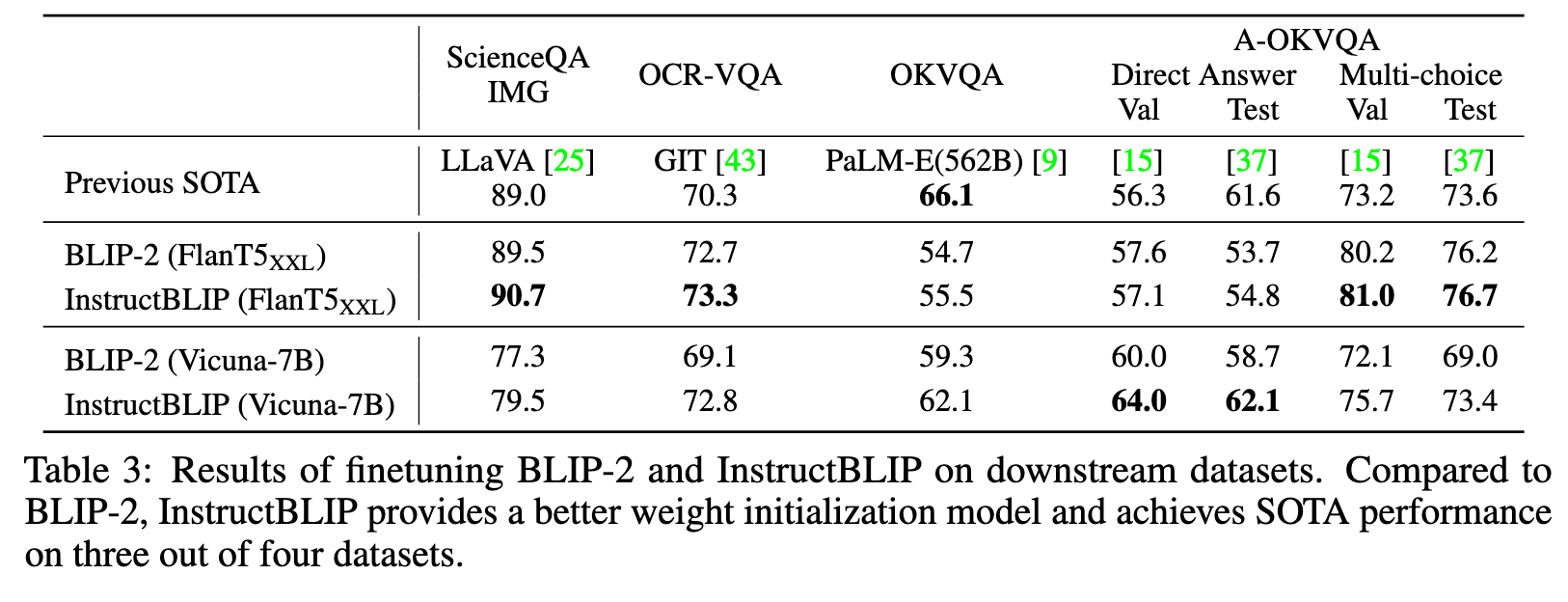

Finetuning InstructBLIP on Downstream Tasks

Compared to most previous methods (e.g., Flamingo, BLIP-2) which increase the input image resolution and finetune the visual encoder on downstream tasks, InstructBLIP maintains the same image resolution (224×224) during instruction tuning and keeps the visual encoder frozen during finetuning. This significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters from 1.2B to 188M, thus greatly improves finetuning efficiency. (p. 8)

Compared to BLIP-2, InstructBLIP leads to better finetuning performance on all datasets, which validates InstructBLIP as a better weight initialization model for task-specific finetuning. (p. 9)

Additionally, we observe that the FlanT5-based InstructBLIP is superior at multi-choice tasks, whereas Vicuna-based InstructBLIP is generally better at open-ended generation tasks. This disparity can be primarily attributed to the capabilities of their frozen LLMs, as they both employ the same image encoder. Although FlanT5 and Vicuna are both instruction-tuned LLMs, their instruction data significantly differ. FlanT5 is mainly finetuned on NLP benchmarks containing many multi-choice QA and classification datasets, while Vicuna is finetuned on open-ended instruction-following data. (p. 9)