TEAL Tokenize and Embed ALL for Multi-modal Large Language Models

[llm multimodal deep-learning text2image teal whisper llm vq-vae audio vq-gan dall-e beit hubert llama-adapter blip blip2 gpt llava This is my reading note for TEAL: Tokenize and Embed ALL for Multi-modal Large Language Models. This paper proposes a method of adding multi modal input and output capabilities to the existing LLM. To this end, it utilizes VQVAE and whisper to tokenize the image and audio respectively. Only The embedded and projection layer is trained . The result is not SOTA.

Introduction

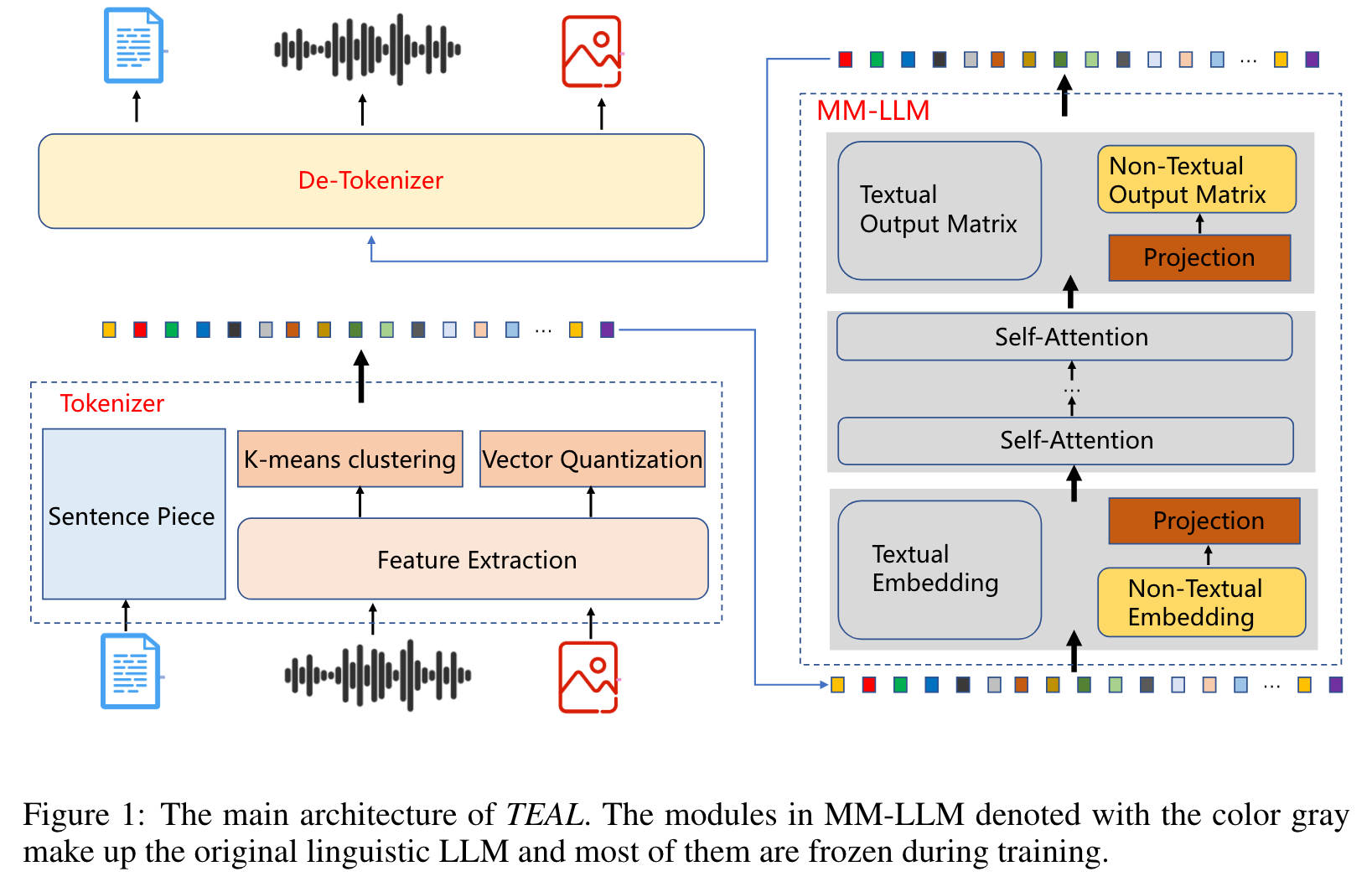

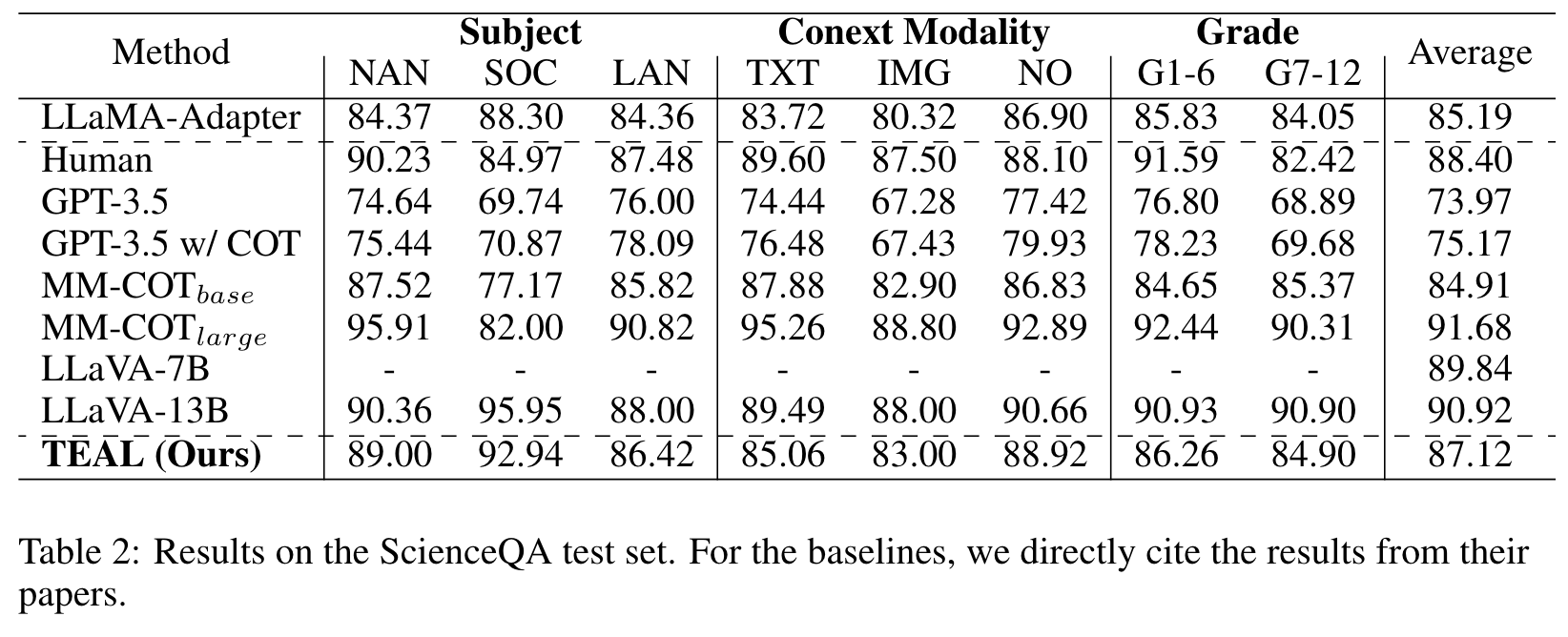

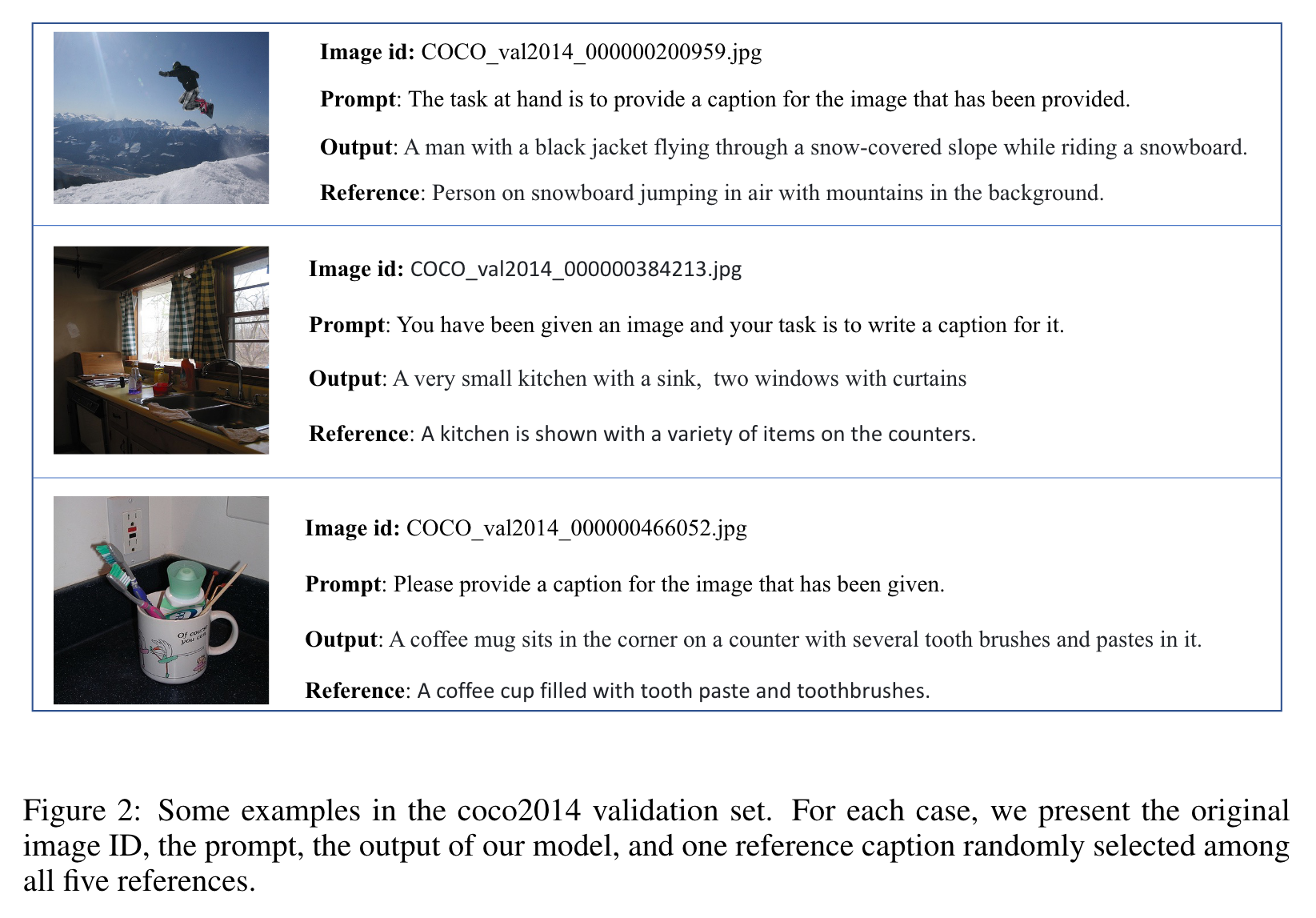

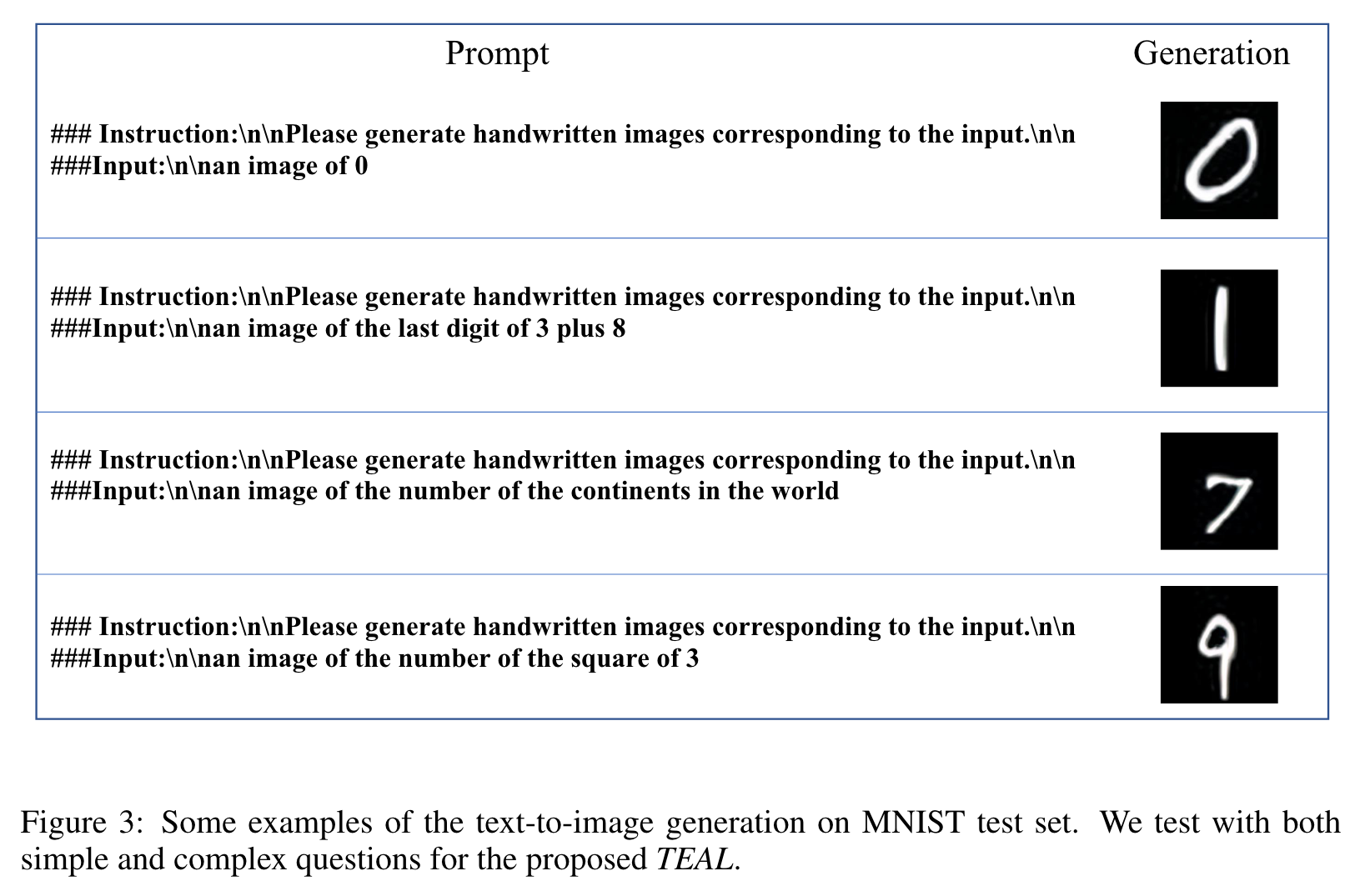

In this work, we propose TEAL (Tokenize and Embed ALl), an approach to treat the input from any modality as a token sequence and learn a joint embedding space for all modalities. Specifically, for the input from any modality, TEAL firstly discretizes it into a token sequence with the off-the-shelf tokenizer and embeds the token sequence into a joint embedding space with a learnable embedding matrix. MM-LLMs just need to predict the multi-modal tokens autoregressively as the textual LLMs do. Finally, the corresponding de-tokenizer is applied to generate the output in each modality based on the predicted token sequence. With the joint embedding space, TEAL enables the frozen LLMs to perform both understanding and generation tasks involving non-textual modalities, such as image and audio. (p. 1)

Typically, there are two main different branches in the realm of constructing MM-LLMs: One branch aims to construct a ‘real‘ multi-modal model by training the model with multi-modal data from scratch, without relying on the pre-trained textual LLMs (Borsos et al., 2023; Lu et al., 2022a; Barrault et al., 2023; Shukor et al., 2023; Chen et al., 2023c; Copet et al., 2023); The other branch takes the textual LLMs as the backbone and enables them to perform multi-modal understanding and generation tasks with instruction tuning. (p. 1)

In this line, some typical works, such as BLIP-2 (Li et al., 2023), Flamingo (Alayrac et al., 2022), MiniGPT-4 (Zhu et al., 2023), LLama-Adapter (Gao et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023c), LLaVA (Liu et al., 2023b;a), SpeechGPT (Zhang et al., 2023a), involve employing adapters that align pretrained encoders in other modalities to textual LLMs. (p. 1)

In order to compensate for this deficiency in the non-textual generation, some efforts, such as visualChatGPT (Chen et al., 2023c), Hugging-GPT (Shen et al., 2023), Audio-GPT (Huang et al., 2023), Next-GPT (Wu et al., 2023b), and MiniGPT-5 (Zheng et al., 2023) have sought to amalgamate the textual LLMs with some external generation tools, e.g., Stable Diffusion (Rombach et al., 2022), DALL-E (Ramesh et al., 2021), Whisper (Radford et al., 2023), and other tools. Unfortunately, these systems suffer from two critical challenges due to their complete pipeline architectures. First, the information transfer between different modules is entirely based on generated textual tokens, where the process may lose some multi-modal information and propagate errors (Wu et al., 2023b). Additionally, the external tools usually make the models complex and heavy, which consequently results in inefficient training and inference. (p. 2)

Based on the above observation, we conclude that the emerging challenges in the previous works are mainly raised by their non-unified processing of the multi-modal inputs, where they encode the non-textual inputs into a dense and high-level feature, but tokenize the linguistic input into a token sequence. (p. 2)

Related Work

Multimodal LLM

Furthermore, different projection layers are used to reduce the modality gap, such as a simple Linear Layer (Liu et al., 2023a) or a two-layer Multi-layer Perceptron (Zhang et al., 2023d). Moreover, LLaMa-Adapter (Zhang et al., 2023c; Gao et al., 2023) integrates trainable adapter modules into LLMs, enabling effective parameter tuning for the fusion of multi-modal information. (p. 3)

Another branch involves using off-the-shelf expert models to convert images or speech into natural language in an offline manner, such as Next-GPT (Wu et al., 2023b), SpeechGPT (Zhang et al., 2023a), AudioGPT (Huang et al., 2023). (p. 3)

NON-TEXTUAL DISCRETIZATION

there are also efforts focused on non-textual discretization, which employs tokenizers to convert continuous images or audio into token sequences. This way, all modalities share the same form as tokens, which can be better compatible with LLM. (p. 3)

VQ-VAEs

- Vector Quantised Variational AutoEncoder (VQ-VAE) (Van Den Oord et al., 2017) is a seminal contribution in the field of non-textual tokenization, which incorporates vector quantization (VQ) to learn discrete representations and converts images into a sequence of discrete codes.

- In the vision domain, VQGAN (Esser et al., 2021) follows the idea, using a codebook to discretely encode images, and employs Transformer as the encoder.

- ViT-VQGAN (Yu et al., 2021) introduces several enhancements to the vanilla VQGAN, encompassing architectural modifications and advancements in codebook learning.

- BEiT-V2 (Peng et al., 2022) proposes Vector-quantized Knowledge Distillation (VQ-KD) to train a semantic-rich visual tokenizer by reconstructing high-level features from the teacher model.

- Ge et al. (2023) proposes SEED and claims two principles for the tokenizer architecture and training that can ease the alignment with LLMs.

- Yu et al. (2023a) introduce SPAE, which can convert between raw pixels and lexical tokens extracted from the LLM’s vocabulary, enabling frozen LLMs to understand and generate images or videos.

- For the audio, Dieleman et al. (2018) utilize autoregressive discrete autoencoders (ADAs) to capture correlations in waveforms.

- Jukebox (Dhariwal et al., 2020) uses a multi-scale VQ-VAE to compress music to discrete codes and model those using autoregressive Transformers, which can generate music with singing in the raw audio domain.

- SoundStream (Zeghidour et al., 2021) employs a model architecture composed of a fully convolutional encoder/decoder network and adopts a Residual Vector Quantizer (RVQ) to project the audio embedding in a codebook of a given size. Defossez et al. (2022), Jiang et al. (2022) also adopt RVQ to quantize the output of the encoder. (p. 3)

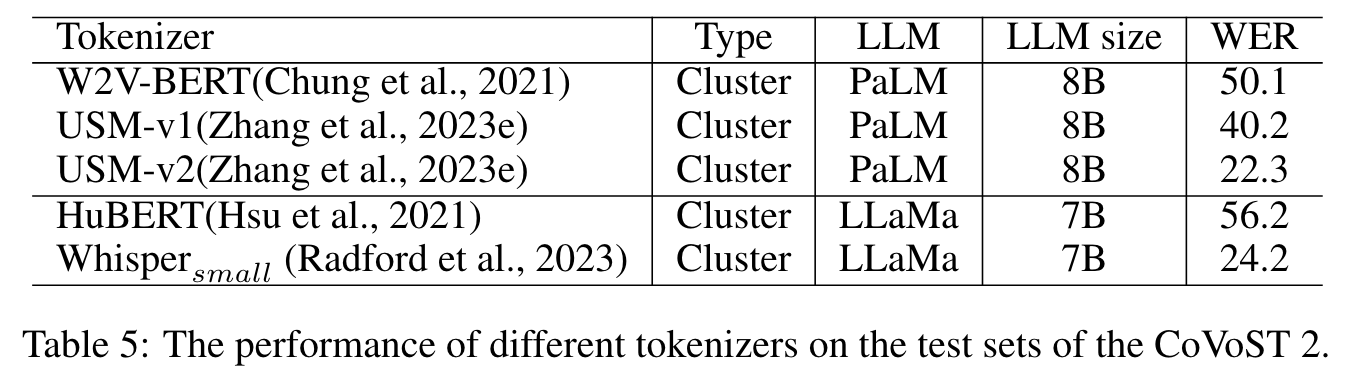

Clustering

some works (Lakhotia et al., 2021; Kharitonov et al., 2022) apply the clustering algorithms to the features, and the cluster indices are directly used as the discrete tokens for speech. The cluster approach typically relies on self-supervised learning models, such as HuBERT(Hsu et al., 2021), W2V-BERT(Chung et al., 2021; Borsos et al., 2023), USM (Zhang et al., 2023e; Rubenstein et al., 2023), which are trained for discrimination or masking prediction and maintain semantic information of the speech. Compared with neural VQ-based tokenizers, the clustering-based approach provides enhanced flexibility as it can be applied to any pre-trained speech model without altering its underlying model structure. (p. 3)

METHOD

To ease the training process and solve the cold-start problem, we initialize the non-textual embedding and output matrix with the codebook of the tokenizer (p. 4)

TOKENIZE AND DE-TOKENIZE

In this paper, we take the encoder of the VQ-VAE models and the k-means clustering as the tokenizers for the image and audio respectively. The decoders of the VQ-VAE models are taken as the de-tokenizers for the image and audio. (p. 4)

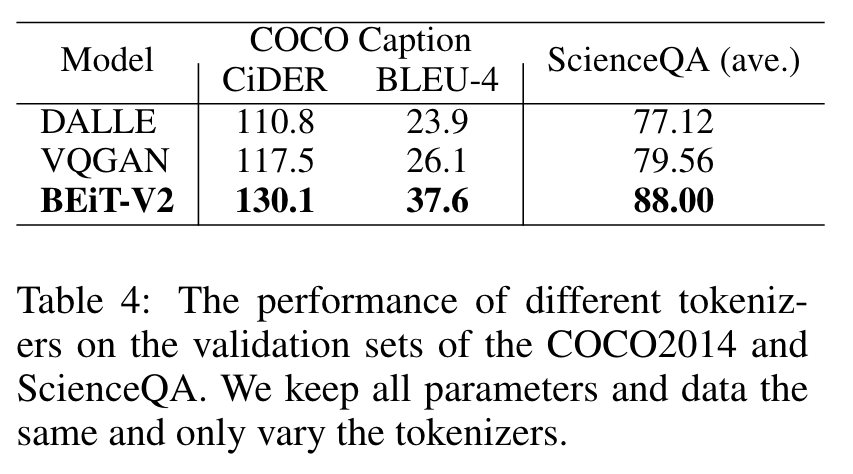

- DALL-E (Ramesh et al., 2021): They train a discrete variational autoen-coder (dVAE) to compress each 256×256 RGB image into a 32 × 32 grid of image tokens, each element of which can assume 8192 possible values. We harness the open-source toolkit implemented by DALLE-pytorch.1 .

- VQ-GAN (Esser et al., 2021): They combine the efficiency of convolutional approaches with the expressivity of transformers by introducing a convolutional VQGAN, which learns a codebook of context-rich visual parts, whose composition is modeled with an autoregressive transformer. We follow the open-source toolkit, Taming-Transformer, and directly use their released pre-trained models.

- BEiT-V2 (Peng et al., 2022): They propose vector-quantized knowledge distillation (VQKD) to train the visual tokenizer, where the tokenizer is trained to reconstruct the semantic features of a teacher model. We utilize the officially released toolkit and models.3 (p. 5)

For the audio, we apply K-means Clustering on the intermediate features of the following typical models, and the cluster indices are directly used as the discrete tokens for speech.

- HuBERT (Hsu et al., 2021): They incorporate an offline clustering step to generate aligned target labels for a BERT-like prediction loss for self-supervised representation learning. Through masked prediction, the model is forced to learn both acoustic and language models from continuous inputs.

- Whisper (Radford et al., 2023): Whisper is a Transformer-based speech recognition model, which is trained on many different speech processing tasks via large-scale weak multilingual and multitask supervision. In this paper, we conduct experiments with the W hispersmall to get discrete audio tokens. (p. 5)

TWO-STAGE SUPERVISED FINETUNING

we propose a two-stage supervised fine-tuning that trains the model with parameters tuned as little as possible. (p. 5)

- Pre-training The goal of the pre-training is to align the non-textual and textual embedding space by tuning the projection layer. Specifically, we freeze all parameters in the MM-LLM except the parameter of the two projection layers. We generate the training samples from the vision-language and audio-language pairs with very simple prompts. Taking the vision-language pair as an example, we generate two training samples from each vision-language pair with the following format:

The image and text pair:[img][text] The text and image pair:[text][img](p. 5) - Finetuning In the stage of finetuning, we process the corpus of downstream tasks as the prompt format in Zhang et al. (2023c). For each task, we use the GPT4 to generate 10 different prompts.4 We freeze the parameters of the textual LLM and tune all parameters related to the non-textual modalities. Following Zhang et al. (2023c), we apply the bias-norm tuning where the bias and norm parameters are inserted in each layer to enhance the finetuning performance. We also tested Lora tuning, but we did not obtain further improvement. (p. 5)

Experiment

Ablation

DIFFERENT TOKENIZERS

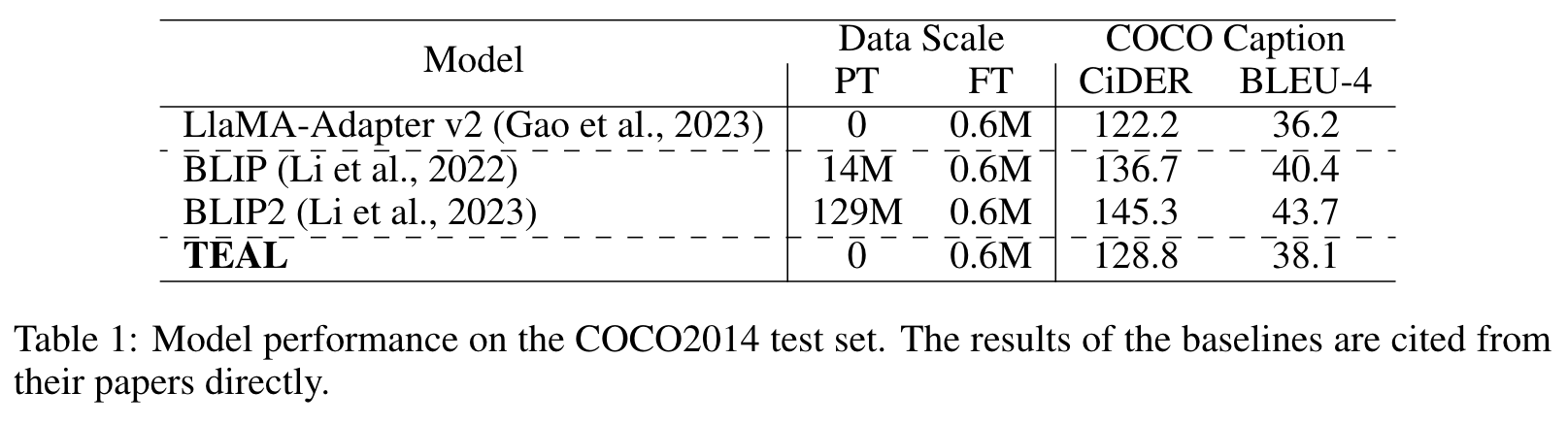

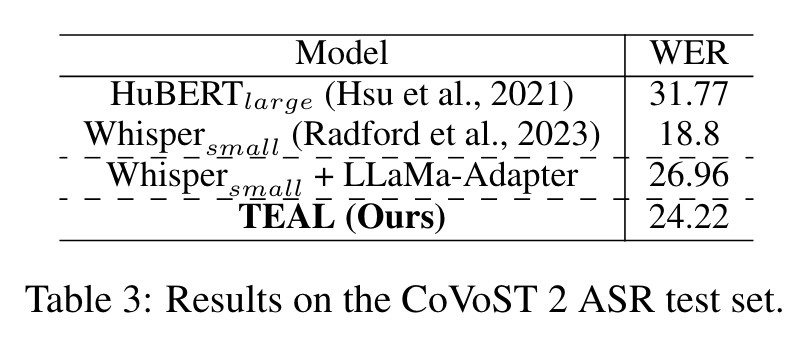

We find that different tokenizers result in significant differences in the final performance, and BEiT-V2 achieves the best result. (p. 8)

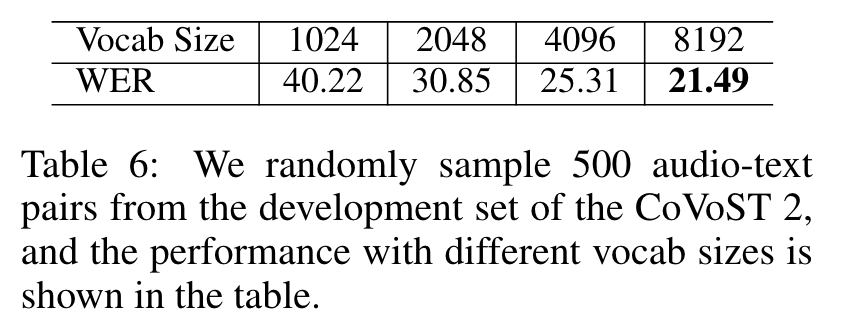

K-MEANS CLUSTER ANALYSIS

We find out that the vocab size has a substantial effect on performance, which makes the clustering-based discretization approaches more versatile than the VQ-based neural codecs for the audio. The former can adjust the vocabulary size by tuning the number of clustering centers, while the latter needs to retrain a vector quantization module. (p. 9)

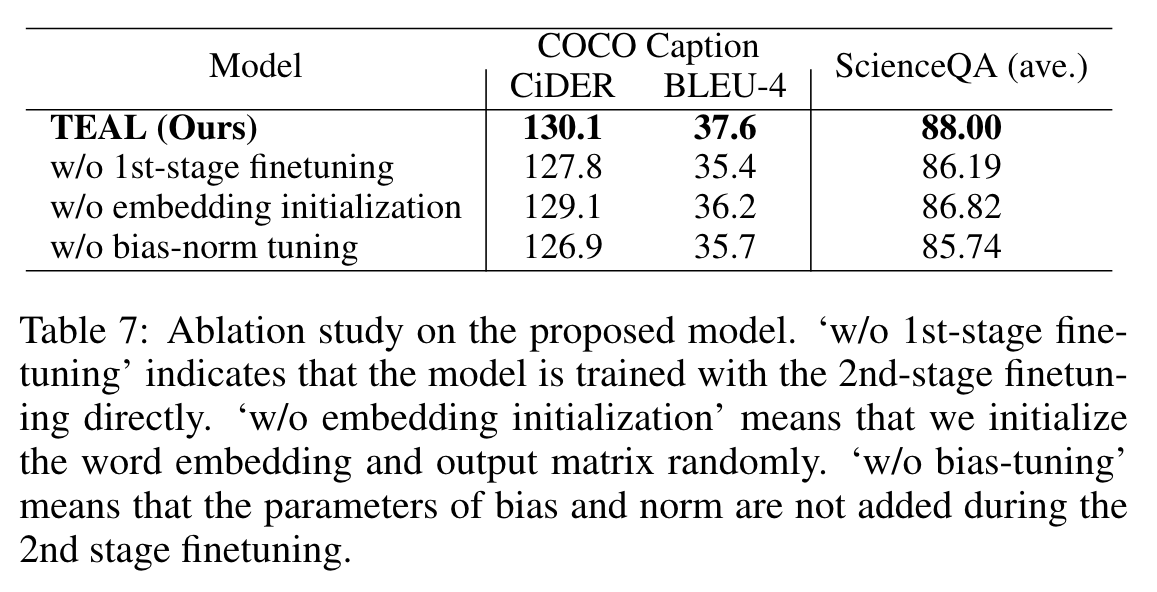

Training Methods

The most critical components are the bias-norm tuning and the 1st-stage finetuning, which shows that the training strategies need to be carefully devised to ensure high performance. A surprising phenomenon is that when we randomly initialize the word embedding (‘w/o embedding initialization’ in Table 7), we do not observe a significant performance decrease. This result suggests that it is the way the tokenizer discretizes the image, rather than the word embedding preserved in the tokenizer, critical to the final performance. The reason why random initialization causes a certain degree of performance decrease is likely due to the relatively small size of the training data. (p. 9)