X-CLIP End-to-End Multi-grained Contrastive Learning for Video-Text Retrieval

[taco multi-grain-attention multimodal video align ablef oscar xclip frozen-in-time clip-bert deep-learning clip clip4clip filip wenlan transformer lxmert video-bert This is my reading note for X-CLIP: End-to-End Multi-grained Contrastive Learning for Video-Text Retrieval. This paper proposes a method on extending clip to video data. it mostly studied how to aggregate the similarity score from the frame level to video level.

Introduction

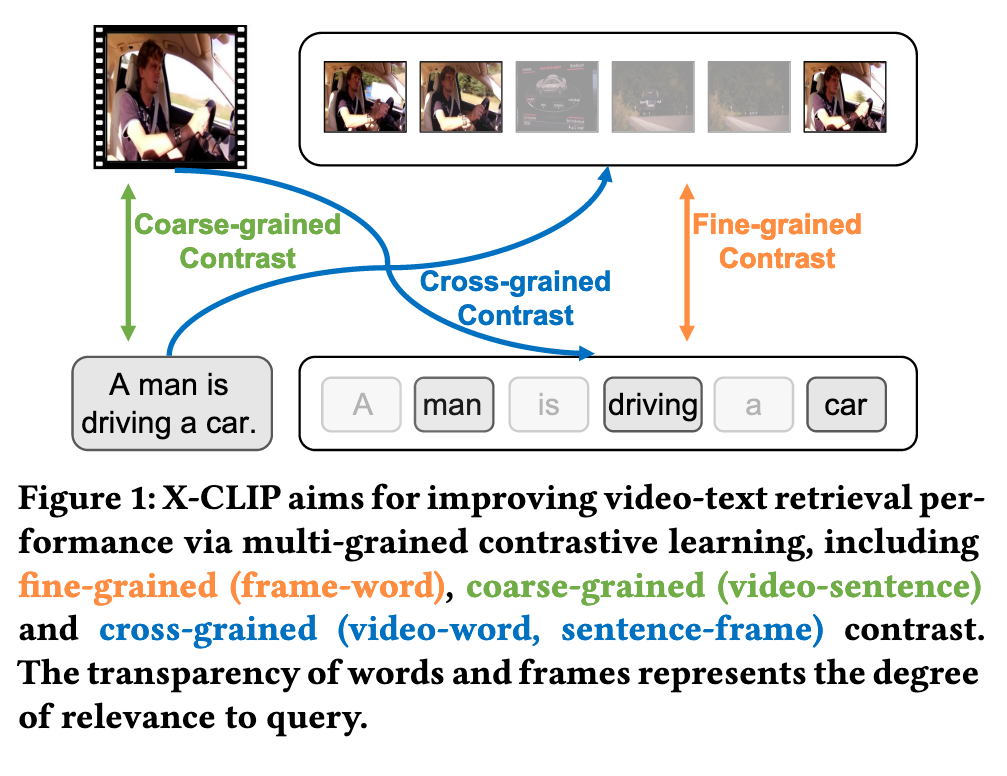

Compared with fine-grained or coarse-grained contrasts, cross-grained contrast calculate the correlation between coarse-grained features and each fine-grained feature, and is able to filter out the unnecessary fine-grained features guided by the coarse-grained feature during similarity calculation, thus improving the accuracy of retrieval. To this end, this paper presents a novel multi-grained contrastive model, namely X-CLIP, for video-text retrieval (p. 1)

To address this challenge, we propose the Attention Over Similarity Matrix (AOSM) module to make the model focus on the contrast between essential frames and words, thus lowering the impact of unnecessary frames and words on retrieval results. (p. 1)

Furthermore, CLIP4Clip [38] transfers the imagetext knowledge of CLIP to the VTR task, resulting in significant performance improvements on several video-text retrieval datasets. However, CLIP and CLIP4Clip embed the whole sentence and image/video into textual and visual representations, thus lacking the ability to capture fine-grained interactions. To this end, some previous works [29, 59] propose fine-grained contrastive frameworks, which consider the contrast between each word of the sentence and each frame of the video. Moreover, TACo [57] introduces tokenlevel and sentence-level loss to consider both fine-grained and coarse-grained contrast. (p. 1)

However, most current works mainly focus on coarse-grained contrast [38, 44], fine-grained contrast [29, 59] or both [57], which are inefficient in filtering out these unnecessary frames and words. (p. 1)

To this end, we ask: How to effectively filter out unnecessary information during retrieval? To answer this question, we propose the cross-grained contrast, which calculates the similarity score between the coarse-grained features and each fine-grained feature. As shown in Fig. 1, with the help of the coarsegrained feature, unimportant fine-grained features will be filtered out and important fine-grained features will be up-weighted. However, challenges in cross-grained contrast arise from aggregating similarity matrices to instance-level similarity scores. A naive and easy method is to use Mean-Max strategy [25, 26, 47, 59] to calculate the instance-level similarity score after obtaining the similarity matrix. However, the conventional Mean-Max strategy is not conducive to filtering out the unnecessary information in videos and sentences during retrieval. On one hand, Mean applies the same weight to all frames and words, so the contrast between unnecessary frames and unimportant words may harm the retrieval performance. On the other hand, Max only considers the most important frame and word, ignoring other critical frames and words. (p. 2)

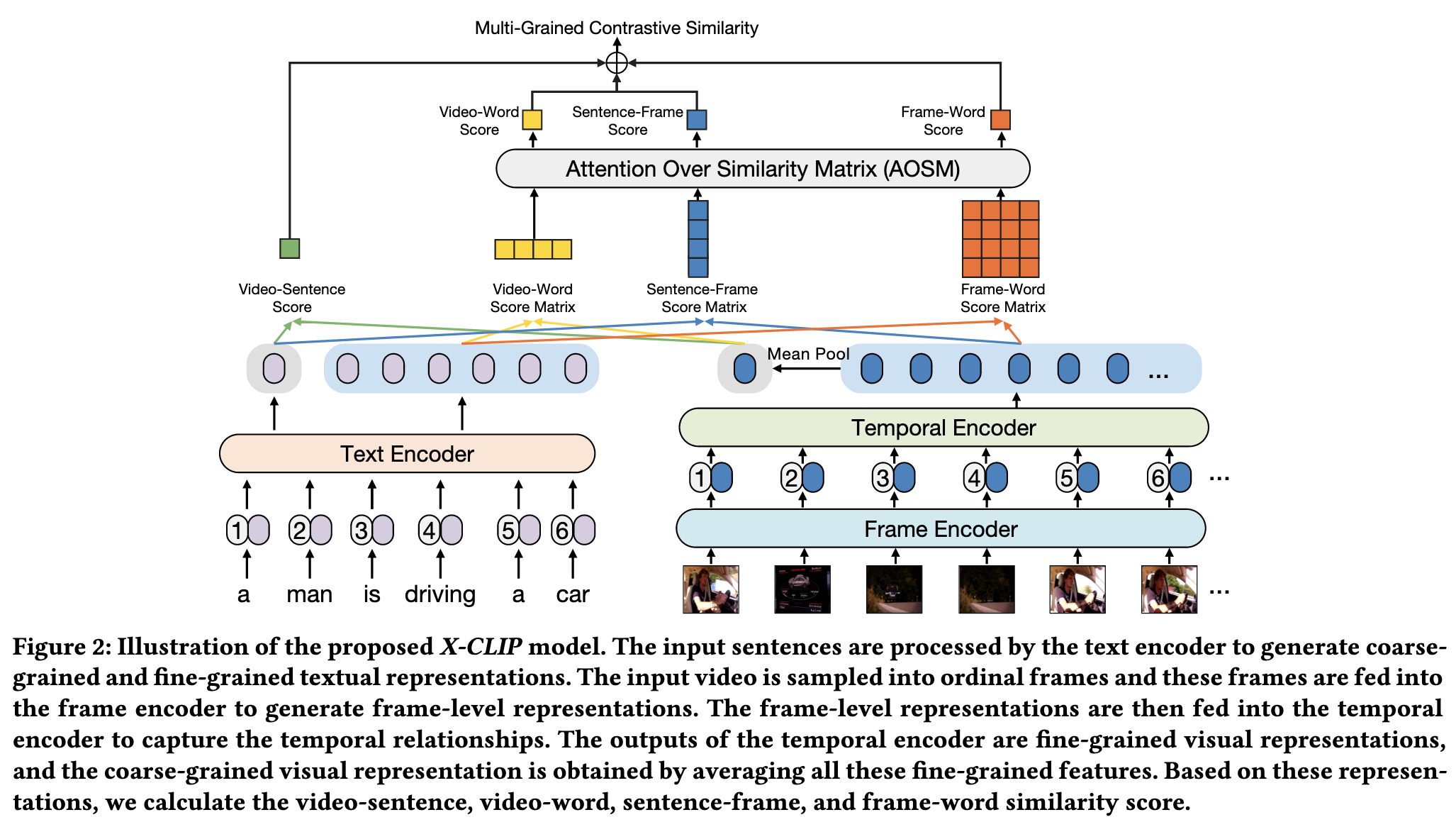

Specifically, X-CLIP first adopts modality-specific encoders to generate multi-grained visual and textual representations and then considers multi-grained contrast of features (i.e., videosentence, video-word, sentence-frame, and frame-word) to obtain multi-grained similarity scores, vectors, and matrices. To effectively filter out the unnecessary information and obtain meaningful instance-level similarity scores, the AOSM module of X-CLIP conducts the attention mechanism over the similarity vectors/matrices. Different from the conventional Mean-Max strategy, our proposed AOSM module dynamically considers the importance of each frame in the video and each word in the sentence, so the adverse effects of unimportant words and unnecessary frames on retrieval performance are reduced. (p. 2)

RELATED WORKS

Vision-Language Pre-Training

One line of work such as LXMERT [51], OSCAR [33] and ALBEF [31] focuses on pre-training on enormous image-text pairs data. To better cope with the image-text retrieval tasks, contrastive language-image pre-training methods such as CLIP [44], ALIGN [23] and WenLan [19] have been proposed, by leveraging billion-scale image-text pairs data from the web with a dual-stream Transformer (p. 2)

The other line of work such as VideoBERT [50], HERO [32] and Frozen in Time [4] directly collects video-text pairs data for video-language pre-training, by further considering the temporal information in videos. (p. 2)

Video-Text Retrieval

ClipBERT [30] proposes to sparsely sample video clips for end-to-end training to obtain clip-level predictions, while Frozen in Time [4] uniformly samples video frames and conducts end-to-end training on both image-text and videotext pairs data. (p. 2)

Multi-Grained Contrastive Learning

CLIP [44] implements the idea of contrastive learning based on a large number of image-text pairs, achieving outstanding performance on several multi-modal downstream tasks [17, 21, 22, 39, 64, 65]. To achieve fine-grained contrastive learning, FILIP [59] contrasts the patch in the image with the word in the sentence, achieving fine-grained semantic alignment. TACo [57] proposes token-level and sentence-level losses to include both fine-grained and coarse-grained contrasts. (p. 3)

METHODOLOGY

Feature Representation

Frame-level Representation

For a video 𝑣ˆ𝑖 ∈ Vˆ, we first sample video frames using the sampling rate of 1 frame per second (FPS). Frame encoder is used to process these frames to obtain frame-level features, which is a standard vision transformer (ViT) with 12 layers. The [CLS] tokens from the last layer are extracted as the frame-level features 𝑣¯(𝑖,𝑗) ∈ V¯ 𝑖. (p. 3)

Visual Representation.

Therefore, we further propose a temporal encoder with temporal position embedding P, which is a set of predefined parameters, to model the temporal relationship. To be specific, the temporal encoder is also a standard transformer with 3 layers, which can be formulated as: (p. 3)

where $V_𝑖 = [𝑣(𝑖,1), 𝑣(𝑖,2), 𝑣(𝑖,3), \dots, 𝑣(𝑖,𝑛)]$ is the final frame-level (fine-grained) visual features for the video 𝑣ˆ𝑖, To obtain video-level (coarse-grained) visual feature 𝑣′ 𝑖 ∈ R^𝑑𝑖𝑚, all frame-level features of the video 𝑣_𝑖 are averaged (p. 3)

Textual Representation

Given a sentence, we directly use the text encoder of CLIP to generate the textual representation, which is also initialized by the public checkpoints of CLIP [44]. (p. 3)

Multi-Grained Contrastive Learning

Previous VTR works [29, 38] focus on fine-grained and coarse-grained contrastive learning, which include video-sentence and frame-word contrasts. (p. 3)

- video-Sentence Contrast. Given the video-level representation 𝑣′ ∈ R𝑑𝑖𝑚 and sentence-level representation 𝑡′ ∈ R𝑑𝑖𝑚, we use matrix multiplication to evaluate the similarity between video and sentence (p. 3)

- Video-Word Contrast. For the given video-level representation 𝑣′ ∈ R𝑑𝑖𝑚 and word-level representation vector T ∈ R𝑚×𝑑𝑖𝑚, we use matrix multiplication to calculate the similarity between the video representation and each word representation (p. 3)

- Sentence-Frame Contrast. Similar to Video-Word Contrast, we can calculate the similarity between the sentence representation 𝑡′ ∈ R𝑑𝑖𝑚 and each frame representation V¯ ∈ R𝑛×𝑑𝑖𝑚 based on matrix multiplication (p. 4)

- Frame-Word Contrast. The fine-grained similarity matrix between word representations and frame representations can be also obtained using the matrix multiplication (p. 4)

Attention Over Similarity Matrix (AOSM)

To address this issue, we propose the Attention Over Similarity Matrix (AOSM) module, where scores in similarity vectors/matrices will be given different weights during aggregation. (p. 4)

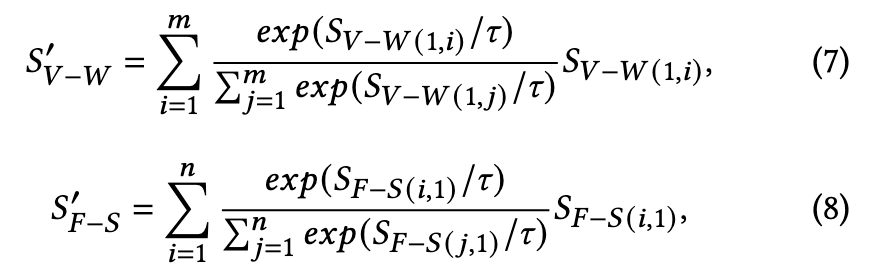

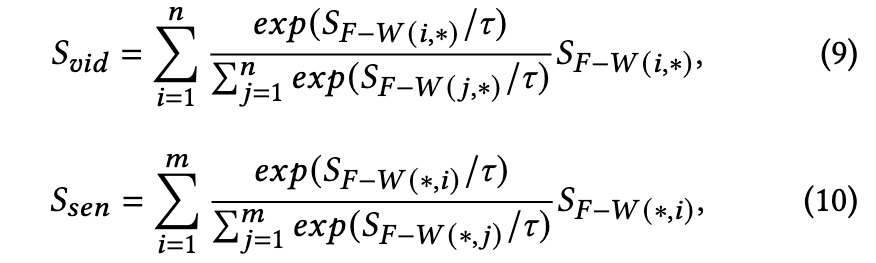

Specifically, given the similarity vectors 𝑆_{𝑉 −𝑊} ∈ R^{1×𝑚} and 𝑆_{𝐹−𝑆} ∈ R^{𝑛×1}, we first use Softmax to obtain the weights for the similarity vector, where scores for the fine-grained features related to the query will be given high weights. Then, we aggregate these similarity scores based on the obtained weights (p. 4)

Since the fine-grained similarity matrix 𝑆_{𝐹−𝑊} ∈ R^{𝑛×𝑚} contains the similarity scores of 𝑛 frames and𝑚 words, we perform attention operations on the matrix twice. The first attention aims to get finegrained video-level and sentence-level similarity vectors, (p. 4)

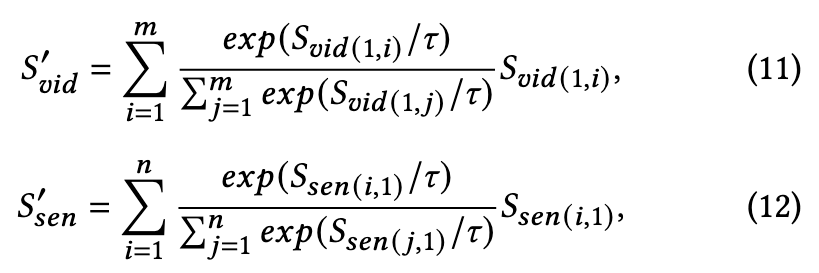

To obtain fine-grained instance-level similarity scores, we conduct the second attention operation on the video-level vector 𝑆_𝑣𝑖𝑑 ∈ R^{1×𝑚} and sentence-level similarity vector 𝑆_𝑠𝑒𝑛 ∈ R^{𝑛×1} (p. 4)

We use the average value as the fine-grained similarity score (p. 5)

Similarity Calculation

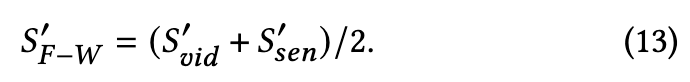

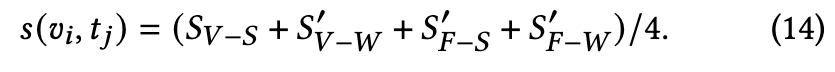

Therefore, the final similarity score 𝑠(𝑣_𝑖, 𝑡_𝑗) of X-CLIP contains multi-grained contrastive similarity scores (p. 5)

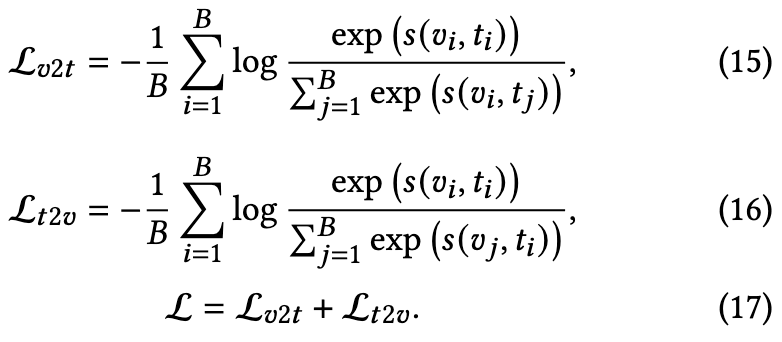

Objective Function

We adopt the symmetric InfoNCE loss over the similarity matrix to optimize the retrieval model, which can be formulated as (p. 5)

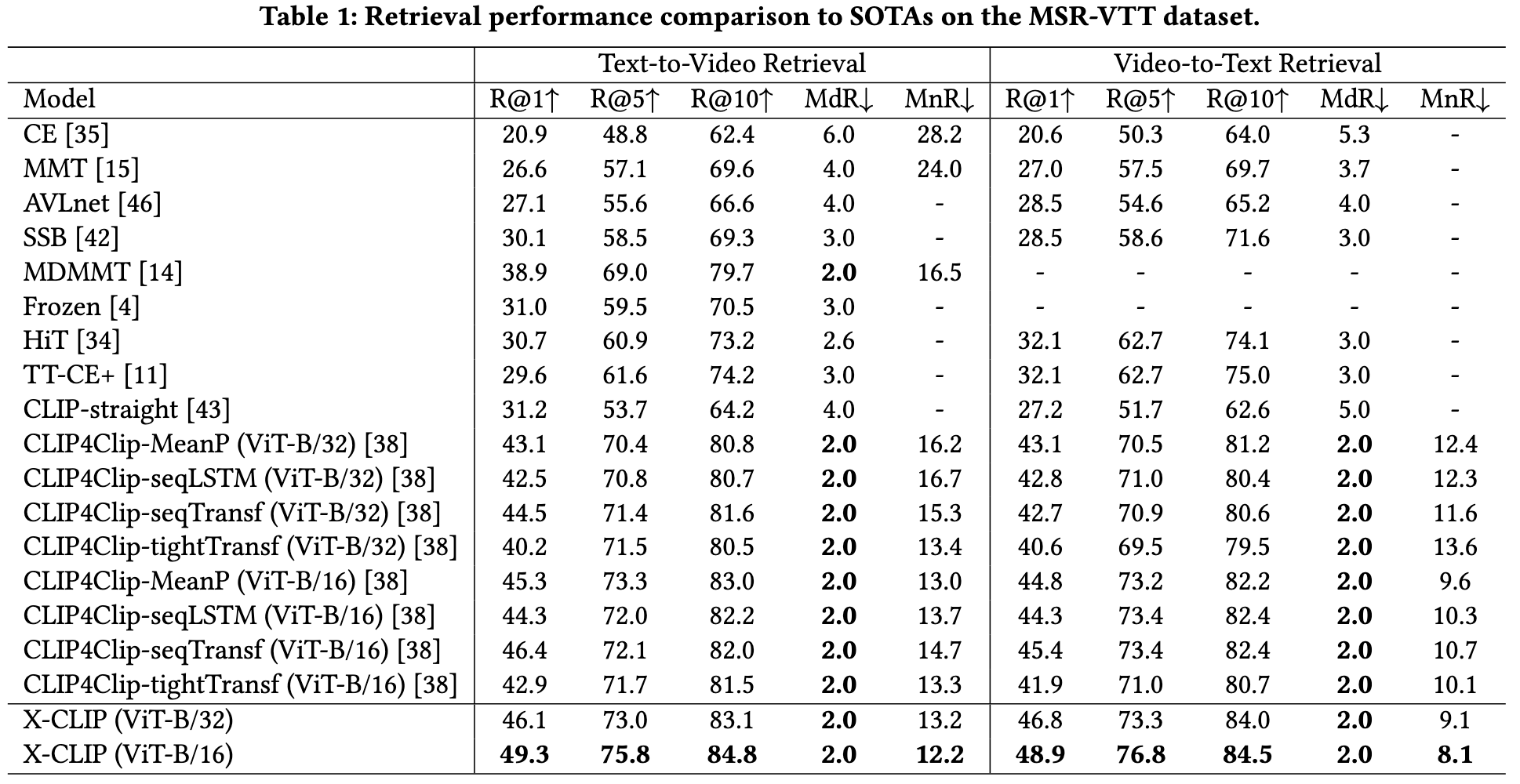

EXPERIMENTS

Ablation Study

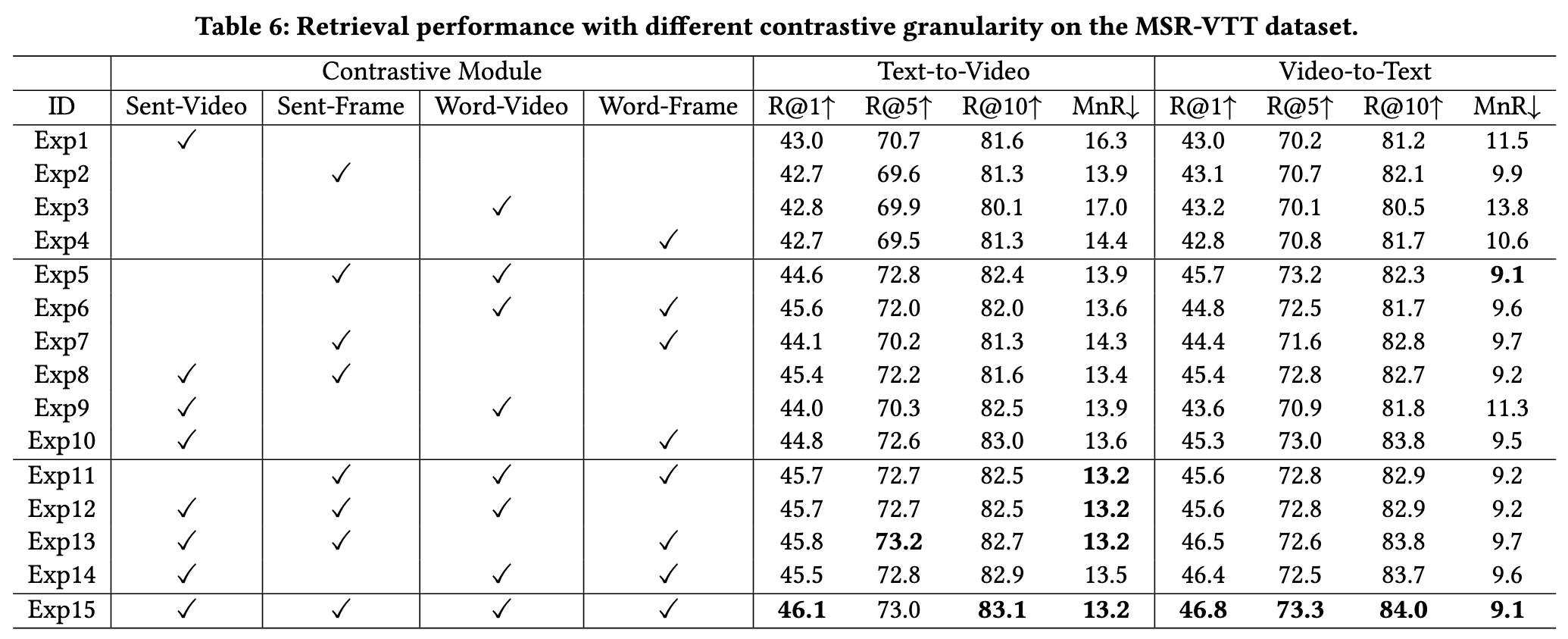

With the number of contrastive modules increasing, the retrieval performance tends to be higher. (p. 7)

Our proposed cross-grained contrast can assist fine-grained contrast or coarse-grained contrast to achieve better performance in the retrieval task (p. 7)

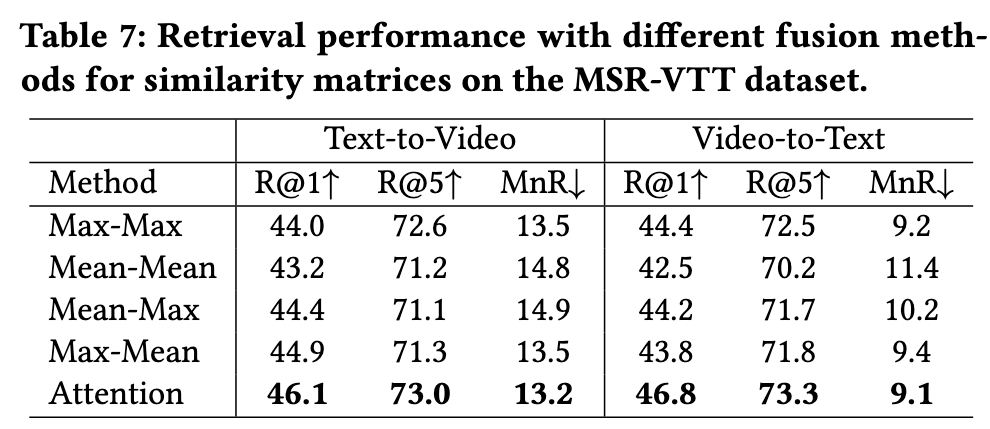

As shown in Tab. 7, we observe that the Mean-Mean strategy performs worst. This may be because the Mean-Mean strategy, which applies the same weight to all similarity scores during aggregating, can not eliminate the adverse effects of unnecessary frames and unimportant words on the retrieval results. The Max-Mean, Mean-Max and Max-Max strategies perform better than the Mean-Mean strategy. This can be attributed to that these strategies adopt the highest similarity during aggregation, so contrast scores between unnecessary frames and unimportant words will be filtered out. However, since these strategies adopt the top-1 similarity score, some important similarity scores will also be ignored. To (p. 7)

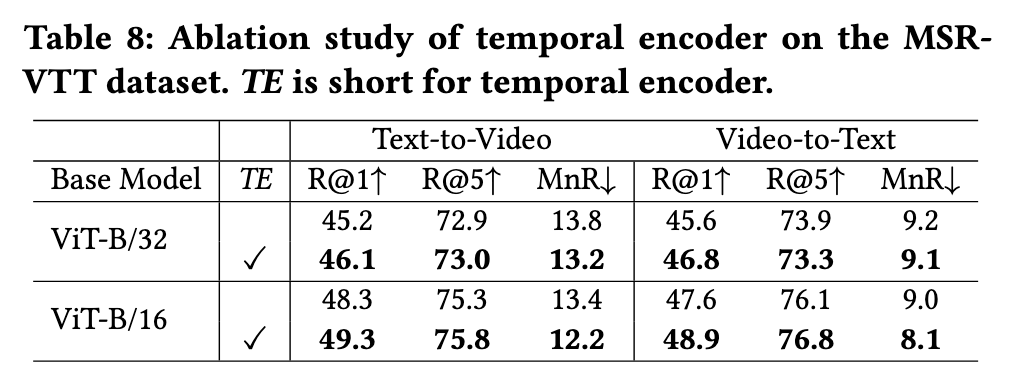

X-CLIP with temporal encoder consistently outperforms X-CLIP without temporal encoder (p. 7)

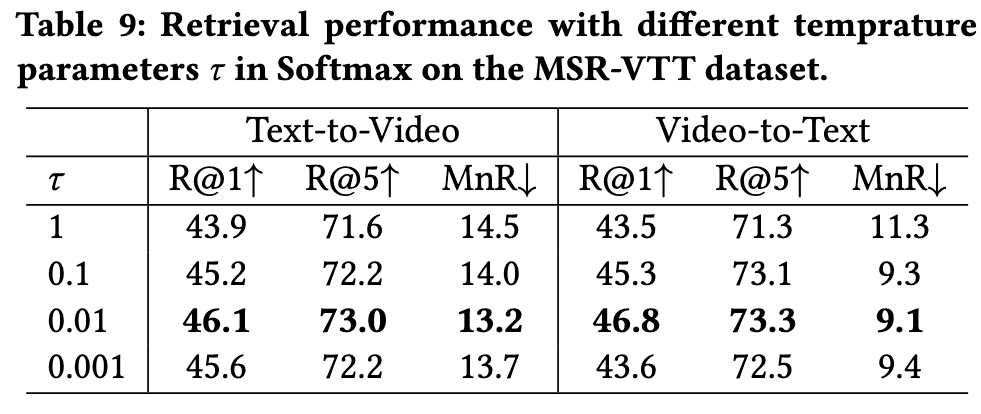

Effect of Temperature Parameter

To explore the effect of different 𝜏 in the AOSM module, we also designed a group of experiments by setting different temperature parameters 𝜏 in Softmax. From Tab. 9, we observe that the retrieval performance first improves before reaching the saturation point (i.e., 𝜏 = 0.01), and then begins to decline slightly. The main reason may be that when 𝜏 is large, too many noisy similarity scores are considered. On the contrary, if the 𝜏 is small, some important similarity scores may be ignored. (p. 7)